Transcription

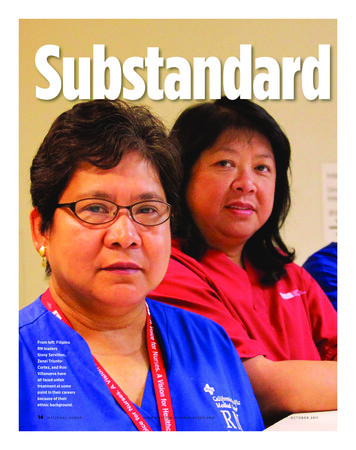

Filipino JulAug 11/29/11 10:09 PM Page 14Substandard CFrom left: FilipinoRN leadersSiony Servillon,Zenei TriunfoCortez, and RonVillanueva haveall faced unfairtreatment at somepoint in their careersbecause of theirethnic background.14N AT I O N A L N U R S EW W W. N A T I O N A L N U R S E S U N I T E D . O R GO C TO B E R 2 0 1 1

Filipino JulAug 11/29/11 10:09 PM Page 15CareDespite being valued andessential members of theAmerican RN workforce,Filipino nurses must still oftenchallenge and overcome biasand discrimination.By Momo Chang“Their accents are hard to understand.”“They all seem to know each other. Are they all related or something?”“Why are they always working? They make so much overtime.”These are the types of coded comments that Filipino registered nurses hear alltoo often in the workplace. While not blatantly racist, these subtle digs belie the prejudice against Filipino nurses that unfortunately still exists among the RN workforce.For Ron Villanueva, a 45-year-old critical care RN with more than 20 years of experience working in the United States, discrimination came in the form of so-called “advice.”Several years ago, when Villanueva tried to apply for a promotion to a managerial post, upper management told him, “I strongly advise you not to apply for theposition.” When he heard that, he flashed back to a previous incident. A year and ahalf prior, while waiting to be interviewed for a supervisor position, he overheard adifferent person in upper management say, “Do not hire foreign graduate nurses.”It wasn’t hard to connect the dots and conclude that his employer, St. Luke’sHospital in San Francisco, appeared to be discriminating against Filipino nurses.Villanueva’s union, the California Nurses Association/National Nurses United,eventually filed in August 2010 a class action grievance on behalf of Filipino nursesat the facility, which is owned by the large corporate hospital chain Sutter Health.“I just wanted people to be treated fairly,” Villanueva said about why he chose tospeak up about the injustice. “Ignorance and intolerance shouldn’t have a placehere, let alone in San Francisco.”And while unfair treatment is often subtle, it can still be shocking and flagrant. Asjust one example, Filipino nurses at Delano Regional Medical Center in California’sCentral Valley allege that Filipinos were the only group singled out by the hospital forenforcement of a stringent English-only policy. The Filipino workers, mostly nurses,were threatened with job loss if they were overheard speaking Tagalog.These incidents, and more, show that prejudice against nurses from other countries and of different ethnicities and nationalities is, sadly, still a part of the workenvironment for many RNs. While discrimination is not just targeted at Filipinonurses, they constitute the largest group of foreign-educated RNs in the UnitedStates. Today, one in four immigrant women from the Philippines are nurses, andFilipino nurses make up 69 percent of all foreign-educated nurses seeking licensesin the United States.O C TO B E R 2 0 1 1W W W. N A T I O N A L N U R S E S U N I T E D . O R GN AT I O N A L N U R S E15

Filipino JulAug 11/29/11 10:09 PM Page 16To understand and hopefully overcome these prejudices, nurses, physicians, and other healthcare workersmust make an effort to understand the culture and backgrounds of their Filipino colleagues and the complex history, rooted in the U.S.-Philippines colonial relationship, thateventually led to waves of immigration by Filipino nurses.“Filipino nurses, as immigrants, have sometimes unfortunately been stereotyped as exploiting the United Statesand as being a detriment to the domestic nursing force,”said Catherine Ceniza Choy, author of Empire of Care:Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History andprofessor in the department of ethnic studies at the University of California at Berkeley. “If you know that historyand you know that U.S. hospitals actively trained andrecruited Filipino nurses after World War II in large numbers, you would learn that Filipino nurses are making animportant contribution to U.S. healthcare delivery.”ilipinos have a long history of working as registered nurses in America. Many were recruited towork in areas or shifts where it was difficult to placenurses, such as in public, inner-city hospitals or ruralareas and for night shifts.To understand that history, one must go back to 1907, when theU.S. colonial government first opened nursing schools in the Philippines. Teaching and training Filipino nurses was seen as a “benevolent” form of colonialism and a way to combat ailments such astuberculosis and cholera. (The U.S. colonial relationship with thePhilippines lasted from 1898 until 1946.) While that early training –the first Filipino nurses graduated in 1911 – was intended for Filipinosto work in the Philippines, it laid the foundation for the eventual massmigration of Filipino nurses to work abroad, according to Choy.Two major factors led to the mass migration of Filipino nursesabroad: facility in the English language, and a U.S.-based nursing education system. Nurses were taught in English within a nursing education system that was very similar to programs in the United States, andthe best and brightest were encouraged to study abroad in America.This education in English and Americanized way of nursing, coupled with nurses’ own desires to visit the United States, paved theway for future nurse migrants. Because it was seen as a booming,high-status field, particularly for women, girls from the most“respectable families” were recruited into nursing programs in thePhilippines, where they lived in dorms in a strict environment.In 1948, the U.S. government created an exchange programcalled the Exchange Visitors Program, which was rooted in ColdWar goals. This led to the first large wave of Filipino exchange nurses here. Between 1956 and 1969, 11,000 Filipino nurses participatedin the program as exchange visitor nurses on two-year contracts.The vast majority of these nurses returned to the Philippines,though there were a number of nurses who remained in the UnitedStates through marriage, by going to Canada, or working with hospital employers to change their status, Choy said.Starting in the 1960s, recruitment agencies began recruiting theseformer exchange nurses to return, either as immigrants or temporaryworkers. Then in 1964, the value of the peso, the currency in thePhilippines, plummeted. The incentive to work in the United Statesgrew even greater. Now nurses from the Philippines could work hereand make ten times as much as they did at home — even if they wereF16N AT I O N A L N U R S Epaid less than their American counterparts. By 1964, half of all Filipinonurses went abroad, according toChoy’s research.When the Immigration Act of1965 passed, it allowed for themass, and permanent, migration ofFilipino nurses to the United States. It gave preference to highlyskilled, professional workers such as nurses. During the 1970s, thePhilippines government focused on labor export as an economicstrategy and relied heavily on remittances, or money sent back fromworkers abroad. Today, many Filipino nurses still send money to relatives in the Philippines and are expected to use their salaries tohelp support a much wider extended family than most Americans.Filipino nurses, in short, became one of the country’s best andmost valuable commodities for export. The growth of Philippinenursing schools reflects the demand: between 1950 and 1970, nursing schools in the Philippines grew from 17 to 140; by 1990, therewere 170 schools, and today, about 300, according to Choy.The United States, coincidentally, had a severe nursing shortage;by 1967, there was a shortage of 125,000 nurses. Filipino nurses whocame to the United States after 1965 qualified not just as “exchangenurses,” but as temporary workers and immigrants.So while the original intent under the U.S.-ruled Philippines government was to create a nurse workforce to serve the Philippines, itset the stage for international migration: In the two decades between1966 and 1985, at least 25,000 Filipino nurses migrated to the United States, according to estimates by Paul Ong and Tania Azores,researchers who have written about Asian American immigration.Teresita Supelana, 60, was one such nurse who came over to theUnited States during a nursing shortage in 1977 at age 24, afterworking in a government hospital in the Philippines for three years.“During that time in the Philippines, you don’t earn that much.When you get a job, it’s not even enough for yourself,” said Supelana,a critical care RN in the coronary care unit at John H. Stroger, Jr.hospital in Chicago. Her father was a farmer and her mother aW W W. N A T I O N A L N U R S E S U N I T E D . O R GO C TO B E R 2 0 1 1NICK UT/AP/CORBISElnora Cayme reacts as shediscusses the lawsuit she andcoworkers filed against DelanoRegional Medical Center forapplying an English-only ruleonly to Filipinos.

Filipino JulAug 11/29/11 10:09 PM Page 17housewife in the Philippines. “One of the reasons why I really wanted to come here was for a greener pasture, for better opportunities,to help my folks back home.”aria asuncion servillon, 60, also felt the pull of the UnitedStates. Servillon was 22 years old and a recent graduate of theUniversity of Santo Tomas College of Nursing when the director of a Kingsport, Tenn.-based teaching hospital landed in Manilaand recruited nurses from her school.“You know, when you’re young, you’re brave,” Servillon, who goesby Siony, says. She, along with about 30 other recruits, were interviewed on the spot and signed up for a short-term contract with thehospital. They headed on a plane from Manila to Tennessee.The opportunity allowed Servillon and her classmates to see theworld, though she calls life upon arrival as a “cultural shock.” In Tennessee in 1973, nearly everyone was black or white, she says. Theyoung nurses also didn’t know how to cook or do many chores, asmany were accustomed to having household help in the Philippines.And at first, the foreign-trained nurses were not accepted by thelocal hospital workers. The nurses’ aids and nurses in training may havefelt threatened by these younger nurses from abroad telling them whatto do, Servillon said. But the Filipino nurses were able to break the cultural barrier and befriend their Southern coworkers. “We invited themto our parties,” Servillon said. “We brought them Filipino food.”After working in the Tennessee hospital for two years, Servillonmoved west to Daly City, Calif., just outside of San Francisco and isnow an evening charge nurse in the ICU at St. Luke’s Hospital whereshe has worked for more than 36 years, in the Mission district of SanFrancisco made up of mostly poor and working-class Latino and Asianimmigrants and African Americans. It’s the same hospital where Villanueva, the RN discouraged from seeking a promotion, works.Servillon counts her blessings that her experience being recruitedwas positive overall. “I could have been recruited by other placesthat did not treat their workers right.”Other nurses who came to the United States were not so lucky.Some had to return to the Philippines when they didn’t passrequired nursing exams. And tales abound of unscrupulousMFilipino Nursesby the NumbersOne in four immigrant womenfrom the Philippines are nursesAbout 69 percent of all foreign-trainednurses seeking licenses in the UnitedStates are from the PhilippinesSources: Migration Policy Institute and American Community Survey,2008; National Council of State Board of Nursing, 2010O C TO B E R 2 0 1 1recruiters and employers who deceive nurses about the type of workthey would do and the working conditions they would have.Nurses were sometimes given the most undesirable shifts, likethe night shift, were paid stipends instead of full wages, or were notpaid overtime wages. Others were assigned work in nursing homesas aids instead of as nurses in clinics or hospitals.“They are vulnerable to exploitation, especially new migrantnurses,” says Choy. “Their work is tied to their migration status. Theybecome vulnerable to overwork, to undercutting of wages, becausethey want to do well and keep their jobs.”This type of exploitation is a “longstanding pattern” that continues today, according to Choy.In 2006, a high-profile case of nurses recruited from the Philippines to work in Long Island came to light, with extensive coveragein the New York Times and Newsday. When the nurses arrived, theyfound that they were not given what was promised, including fairwages and benefits and decent working conditions in a nursinghome. A lawyer advised the nurses that their employer had breachedtheir contracts and 24 workers resigned en masse.In response, SentosaCare, their employer, filed a civil suit against10 of the workers for breach of contract and patient abandonment.The nurses then countersued and filed a complaint against therecruiting arm of the company in the Philippines, with the Philippines government temporarily halting the company’s recruitingprivileges. In May 2010, the nurses were successful in court and ajudge decided they did not have to pay the recruitment agency up to 25,000 in damages. But the case stands out as an example of howunethical recruitment of Filipino nurses is an ongoing problem.“It’s a big victory for migrant nurses, especially Filipino nurses,” saidZenei Triunfo-Cortez, RN and co-president of the California NursesAssociation. “Hopefully, we are encouraging nurses, if they believe theyare being discriminated against or favored over others, to speak up.”In addition to unethical recruiters, constantly changing immigration laws and government policies also put Filipino nurses recruitedfrom abroad in precarious situations.Noreen David Brion, 49, a critical care RN at Mountain ViewHospital in Las Vegas, Nev., and a negotiating team member of herunion, spent several months running away from immigration whenshe f

University of Santo Tomas College of Nursing when the direc-tor of a Kingsport, Tenn.-based teaching hospital landed in Manila and recruited nurses from her school. “You know, when you’re young, you’re brave,” Servillon, who goes by Siony, says. She, along with about 30 other recruits, were inter- viewed on the spot and signed up for a short-term contract with the hospital. They headed .