Transcription

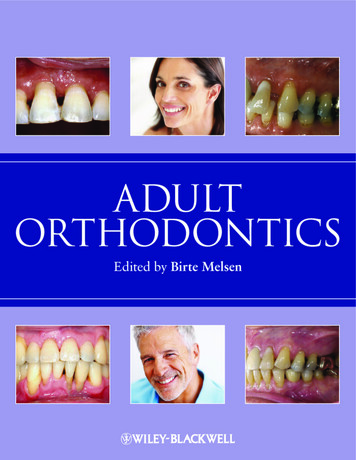

AdultOrthodonticsEdited byBirte MelsenSchool of Dentistry, Aarhus University, DenmarkA John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication

This edition first published 2012 2012 by Blackwell Publishing LtdBlackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged withWiley’s global Scientific, Technical and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.Registered office: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UKEditorial offices: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK2121 State Avenue, Ames, Iowa 50014-8300, USAFor details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse thecopyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designsand Patents Act 1988.All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by anymeans, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and PatentsAct 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product namesused in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is notassociated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritativeinformation in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in renderingprofessional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should besought.Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataAdult orthodontics / edited by Birte Melsen.p. ; cm.Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 978-1-4051-3619-8 (hardback)I. Melsen, Birte.[DNLM: 1. Orthodontics, Corrective. 2. Adult. WU 400]617.6'43–dc232011034162A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronicbooks.Set in 10/12 pt Minion by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited, Hong Kong12012

Dedicated toAlain who wrote this book with me,and to all the people who helped me during the process.

ContentsList of ContributorsIntroduction: More than a Century of Progress in Adult Orthodontic Treatment123Potential Adult Orthodontic Patients – Who Are They?xixiii1Birte MelsenIntroductionWho are the patients?How do the patients express their needs?The first visitCommunicating with the patientSummaryReferences116791010Diagnosis: Chief Complaint and Problem List12Birte Melsen, Marco A MasioliIntroductionWork-up of a problem list – the interview – chief complaintGeneral healthClinical examinationExtraoral examinationExtraoral photographsFunction of the masticatory systemIntraoral analysis – oral healthEvaluation of dental casts – arch formOcclusal analysisSpace analysisCephalometric analysisFinal problem listIndication for treatmentThe presentation of the problem list – the tip of the icebergConcluding 3Aetiology35Birte MelsenIntroductionBiological backgroundAetiology of malocclusions in adultsAge-related changes in the skeletonAge-related changes in the craniofacial skeletonAge-related changes in the local environmentConsequences of deterioration of the dentitionCase reportsConclusionReferences35354142464648495052

vi45678ContentsInterdisciplinary Versus Multidisciplinary Treatments54Birte MelsenInterdisciplinary or multidisciplinary treatmentsEstablishment of an interdisciplinary teamTreatment sequenceEssential and optional treatment proceduresInteraction during treatmentPost-orthodontic treatmentPatient satisfactionExamples of interdisciplinary casesReferences545658596162626363Treatment Planning: The 3D VTO64Birte Melsen, Giorgio FiorelliDetermining the treatment goalProducing an occlusogramCombining the occlusogram with the head filmThe computerized occlusogramResponding to patients’ needsOrthodontic treatment: Art or science?References64646972737376Tissue Reaction77Carlalberta Verna, Birte MelsenOrthopaedic effectsOrthodontic effects in adult patientsReferences777895Appliance Design99Birte Melsen, Giorgio Fiorelli, Delfino Allais, Dimitrios MavreasIntroductionDefinition of the necessary force systemAnchorage evaluationSequencing the treatment into phasesAppliance selection and designSliding mechanicsSegmented 28129Anchorage ProblemsBirte Melsen, Carlalberta VernaIntroductionDefinitionClassification of anchorageIntramaxillary anchorageSoft tissue anchorageFree anchorageIntermaxillary anchorageOcclusionDifferential timing of force applicationExtraoral anchorageSkeletal 44145160

Contents9Bonding Problems Related to Adult Rehabilitated DentitionsVittorio Cacciafesta, M Francesca Sfondrini, Carmen GiudiceIntroductionBracketsBasics of bondingBonding to crowns and restorationsDebondingReconditioning of stainless steel attachmentsBandingAuxiliary attachmentsReferences10Material-related Adverse Reactions in OrthodonticsDorthe Arenholt BindslevIntroductionFixed appliancesBonding and banding materialsRemovable appliancesMiscellaneous materialsConcluding remarksReferences11Patients with Periodontal ProblemsBirte MelsenPrevalence of periodontal diseaseMalocclusion and periodontal diseaseOrthodontics and periodontal diseaseIndications for orthodontic treatment in periodontally involved patientsTreatment of patients with flared and extruded upper incisorsTissue reaction to intrusion of teeth with horizontal bone lossTreatment of patients with vertical bone defectsWhat are the periodontal limits for orthodontic tooth movement?Sequence of treatment in periodontally involved patientsConclusion regarding Influence of orthodontic treatment on periodontal statusReferences12A Systematic Approach to the Orthodontic Treatment of PeriodontallyInvolved Anterior TeethJaume JanerSingle tooth gingival recessionProgressive spacing of incisorsCase reportsManagement of periodontally involved teethReferences13Interdisciplinary Collaboration Between Orthodontics and PeriodonticsFrancesco Milano, Laura Guerra MilanoIntroductionPeriodontal diagnosisHistory taking, clinical and radiographic examinationScreening for periodontal diseaseLocal factors predisposing to periodontal therapyTiming of ortho-perio treatmentPeriodontal therapySurgical 234234238241245258261261262262262264264265271

viiiContentsMucogingival and aesthetic surgeryRegenerative surgical therapySupportive periodontal treatmentOrtho-perio and multidisciplinary clinical casesConclusionAcknowledgementsReferences1415The Link Between Orthodontics and Prosthetics291291301303307308308Patients with Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Problems310Patients with Temporomandibular DisordersPeter SvenssonIntroductionClassification and epidemiologyDiagnostic proceduresRisk factors and 17291Yves SamamaIntroductionEdentulousness and space management: the mesiodistal dimensionThe vertical dimensionOrthodontics, periodontal disease and prosthetic splintingConclusionAcknowledgementsReferencesBirte MelsenOrthodontics and dysfunctionControversy in the literature regarding TMD and occlusionTreatment and TMDTreatment of clicking jointsOrthodontic treatment of patients with TMDOrganization of the 88Invisalign : as Many Answers as QuestionsRainer-Reginald MiethkeIs Invisalign new?How does Invisalign work?What are the pre-treatment considerations?How does the Invisalign System differ from conventional orthodontics?What characterizes patients seeking Invisalign treatment?What is the most favourable approach to resolving crowding in Invisalign patients?How can the alternatives to IER be evaluated?What are the problems related to resolution of crowding?When are extractions indicated?Does an Invisalign treatment plan differ from a regular orthodontic treatment plan?How does one take an adequate impression for the Invisalign System?What is required to be evaluated in ClinCheck ?What material are aligners made of?What are aligner 45347347

ContentsHow are attachments fabricated on the teeth?What has to be controlled after insertion of aligners?What are the consequences of good or poor aligner fit?What if an aligner is lost?What can be done if a severe discrepancy between ClinCheck and the clinical situationbecomes evident during treatment?What can be done if a slight discrepancy between ClinCheck and the clinical situationbecomes evident at the end of treatment?How can complications during treatment with the Invisalign system be avoided?References18Progressive Slenderizing TechniquePablo EcharriDefinition and objectivesAnthropological justification of slenderizingInfluence of slenderizing on dental plaque, caries and periodontal diseaseIndicationsContraindicationsAdvantages of slenderizingHow much enamel can be stripped?Special considerationsInstrumentation for slenderizingProgressive slenderizing techniqueCase reportsReferences19Post-treatment MaintenanceBirte Melsen, Sonil KaliaStability?Biological maintenanceMechanical maintenance – retentionIntermaxillary retentionActive retention platesConclusionReferences20What are the Limits of Orthodontic Treatment?Birte MelsenWhat determines the limits?ReferenceIndexVisit the supporting companion website for this book: 378380380380382382383385

List of ContributorsDelfino Allais MScCertified Specialist in OrthodonticsPrivate PracticeTorino, ItalyMarco Antônio Masioli PhD, MScProfessor of DentistryFederal University of Espírito Santo (UFES)BrazilDorthe Arenholt Bindslev DDS, PHDAssociate Professor, Certified Specialist in OrthodonticsSchool of DentistryAarhus UniversityAarhus, DenmarkDimitrios Mavreas DDS, MS, Dr DentPrivate PracticeChalandri, GreeceVittorio Cacciafesta DDS, MSc, PhDCertified Specialist in OrthodonticsPrivate PracticeMilano, ItalyandAssistant Clinical ProfessorDepartment of OrthodonticsUniversity of PaviaPavia, ItalyPablo Echarri DDSPresident of the Scientific Committee of Catalonian DentalAssociation (COEC)andPresident of the Ibero-American Society of LingualOrthodontics (SIAOL)andVisiting Professor of Master in Orthodontics at theUniversity of SevillaBarcelona, SpainGiorgio Fiorelli MD, DDSSpecialist in OrthodonticsOrthodontic DepartmentUniversity of SienaandSchool of Specialization/Postgraduate Master CourseSiena, ItalyCarmen Giudice DDSPostgraduate ResidentDepartment of OrthodonticsUniversity of PaviaPavia, ItalyJaume Janer DDS, MDPostgraduate in OrthodonticsCertified Specialist in OrthodonticsPrivate PracticeBarcelona, SpainSonil Kalia B.D.S., L.D.S.R.C.S., MOrth.R.D.C MScSpecialist in Orthodontics (private practice)Visiting Assistant Clinical ProfessorOrthodontic DepartmentAarhus, DenmarkBirte Melsen DDS, Dr OdontProfessor, Head of DepartmentSchool of DentistryAarhus UniversityAarhus, DenmarkRainer-Reginald Miethke Prof em Dr med DentSenior Consultant in OrthodonticsDental DepartmentHamad Medical CorporationDoha, QatarFrancesco Milano DDSPrivate PracticeBologna, ItalyLaura Guerra Milano DDSCertified Specialist in OrthodonticsPrivate PracticeBologna, ItalySheldon Peck DDS, MScDAdjunct Professor of OrthodonticsSchool of DentistryUniversity of North CarolinaChapel Hill, North Carolina, USAand formerlyClinical Professor of Developmental BiologyHarvard School of Dental MedicineBoston, Massachusetts, USAYves Samama DDSCertified SpecialistPrivate PracticeParisandFormer Assistant ProfessorParis Descarte UniversityFranceM Francesca Sfondrini DDSCertified Specialist in OrthodonticsAssistant Clinical ProfessorDepartment of OrthodonticsUniversity of PaviaPavia, Italy

xii List of ContributorsPeter Svensson DDS, PhD, Dr OdontProfessorDepartment of Clinical Oral PhysiologyMINDLab, Center of Functionally Integrative NeuroscienceAarhus University HospitalSchool of DentistryAarhus UniversityAarhus, DenmarkCarlalberta Verna DDS, PhDAssociate ProfessorandCertified Specialist in OrthodonticsSchool of DentistryAarhus UniversityAarhus, Denmark

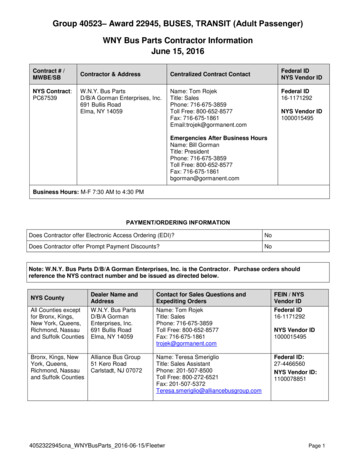

Introduction: More than a Century of Progressin Adult Orthodontic TreatmentOrthodontics for adults is not new. A hundred years agoand earlier, orthodontics was considered a division of prosthetics in the minds of most dentists. The problems relatedto the common loss of permanent teeth from uncontrolledcaries were among the most frequent chief complaints ofadult patients evaluated for ‘orthodontia.’ Unwitting extraction of posterior teeth during youth allowed adjacent teethto tip into the spaces over time. Often, orthodontic uprighting of tipped teeth in adult patients was performed by thesame doctor who afterward prepared the teeth as anchorunits for fixed or removable dental prostheses.We are fortunate to have details of an adult orthodontictreatment performed by Edward H. Angle, MD, DDS(1855–1930), the man acknowledged worldwide as the firstspecialist in orthodontics. In addition to his skill at creatingingenious ‘tooth-regulating’ appliances, Angle was a boldand talented clinician. In 1901 a 38-year-old woman, Mrs.‘A’, came to him from Louisville, Kentucky, referred by herdentist. She was from a leading Kentucky family and shetraveled the 400 kilometers to Dr. Angle’s office in St. Louis,Missouri, because of his reputation as the ‘world’s best’clinical orthodontist.Mrs. ‘A’s four permanent first molars, all healthy, were‘sacrificed’ at nine years of age by a dentist who said thiscourse of action would prevent the development of malocclusion of the other teeth. She came to Dr. Angle threedecades later with severe tipping of the mandibular molarsinto the extraction sites (Fig. 0.1a,b). In the maxillary dentalarch, complete closure of the first molar sites had occurredwith associated retroclination of the anterior teeth and lossof lip support. Furthermore, Angle reported that ‘not onlyhave the remaining teeth been rendered almost useless formastication, but in recent years there has been chronic pericementitis, resulting from wrongly directed force from themolars in their tipped and abnormal positions’ (Angle1903, 1907).A century ago, orthodontic treatment was not frequentlyundertaken for adult patients. Dentists perceived graveuncertainties of response and outcome associated withorthodontic tooth movement in adults, regardless of theirabsolute need for improved dental health. Even the greatDr. Angle was doubtful in his prognosis for Mrs. ‘A’, sayingher age was ‘the most advanced age recorded for such anextensive operation’ (Angle 1903, 1907).Nonetheless, Angle commenced a pre-prosthetic orthodontic treatment for his patient. He used his own designof nickel-silver fixed appliances to regain the lost spaces ofthe four first molars in preparation for fixed bridgework.First, Angle placed bands with buccal tubes (his ‘D-bands’)on the second molars. He then fabricated heavy labialarches (‘E’ arches) for insertion into the tubes to providethree-dimensional expansion of both dental arcades. Inaddition to regaining the lost molar spaces, he wanted toprocline the anterior teeth, ‘lengthen the bite’ and give Mrs.‘A’s lips more support for better facial esthetics. She was avery cooperative patient and all objectives were met withinsix months of treatment (Fig. 0.2 a,b). Angle was elated thather ‘teeth were moved as easily and as rapidly as is usual inthe case of a miss of eighteen, and with no unfavorablesymptoms following the movement of any of the teeth’(Angle 1903, 1907). After active treatment, vulcanite removable plates were fitted for an additional six months of retention, until the teeth were set firmly enough in their newpositions to receive space-filling bridgework from herdentist in Louisville.Dr. Angle was proud of Mrs. ‘A’s treatment results andincluded her case in his published lectures and textbook(Angle 1903, 1907). In these written accounts, he describedMrs. ‘A’ as 38 years old. But in his private correspondencefrom 1899 to 1910 – recently available to us (Peck 2007) –he consistently referred to her as a woman of 42 years.Perhaps a sympathetic Angle made her appear four yearsyounger in his professional publications as a concession tothe vanity of this charming adult patient, whom his lettersshow he held in high esteem.Today, adult orthodontics involves much more thanregaining lost arch space. The enlightening chapters in thisbook demonstrate an unrestricted range of orthodontic

xiv Introduction: More than a Century of Progress in Adult Orthodontic Treatment(1)(2)Fig 0.1(1)Fig 0.2(2)

Introduction: More than a Century of Progress in Adult Orthodontic Treatmentproblems and solutions for the adult patient that more thanmatch those associated with conventional adolescent treatments. Adult orthodontics demands additional skills, suchas the ability to work with compromised dentitions and toaccept less-than-ideal results as the best possible outcomein many cases.We often have several choices in adult treatment plans.Sometimes financial cost becomes a significant factor fromthe adult patient’s point of view. We must seriously attemptto weigh the costs of various treatment alternatives againstthe technical virtues of each. As socially sensitive clinicians,we must acknowledge differences within each society andbetween societies in the ability to absorb escalating costs ofcertain procedures. For example, consider the problem of aspace resulting from the loss or absence of a tooth, that canbe managed by either space reopening or space closingmethods. Within a free-market healthcare system, the combined costs of pre-prosthetic orthodontics and a dentalimplant with crown are often greater than a full-treatmentorthodontics fee. Thus, it may be economically prudent tomanage the space in this instance with orthodontic closurerather than with a multidisciplinary prosthetics solution.If we may speculate based on the historical record,Edward H. Angle would likely be very pleased with thiselaborately designed book on adult orthodontics. It contains the elements he considered essential for solid scientificproblem-solving. First, the diagnostic aspects and problemsare clearly defined. Then, various solutions and limitationsare elucidated in the simplest terms possible, using casestudies. Beautifully illustrated case reports are featured in asupplemental CD disk which is conveniently provided ina pocket on this book’s inside cover. And finally, Anglexvgreatly respected those who explained and thoughtfullyencouraged new and promising materials, methods andtechniques.Birte Melsen is exceptionally well suited to the task oforchestrating the production of a state-of-the-art text onadult orthodontics. She is both a biologic researcher and atalented, experienced clinician. She knows how to planpractical, biologically sound treatments and she has pioneered innovative therapeutic pathways. Dr. Melsen, withthe contributed expertise of her extremely capable teamof hands-on authorities, has given us a book that willsurely extend the boundaries of the specialist’s abilities andvision in the management of complex adult orthodonticproblems.Sheldon Peck, DDS, MScDAdjunct Professor of OrthodonticsSchool of DentistryUniversity of North CarolinaChapel Hill, North Carolina, USA(formerly Clinical Professor of Developmental BiologyHarvard School of Dental MedicineBoston, Massachusetts, USA)ReferencesAngle EH (1903) Some basic principles in orthodontia. Int Dent J 24,729–768.Angle EH (1907) Treatment of Malocclusion of the Teeth: Angle’s System,7th edn, p. 438–445. Philadelphia, PA: SS White Dental Manufacturing.Peck S (ed.) (2007) The World of Edward Hartley Angle, MD, DDS: HisLetters, Accounts and Patents, 4 volumes. Boston, MA: EH AngleEducation and Research Foundation.

1Potential Adult Orthodontic Patients – WhoAre They?Birte MelsenIntroduction 1Who are the patients? 1How do the patients express their needs? 6The first visit 7How can the orthodontist advise such patients? 7Communicating with the patient 9Summary 10References 10IntroductionThe number of adult patients receiving orthodontic treat ment is increasing worldwide. According to the editor ofthe Journal of Clinical Orthodontics, the time when ortho dontics was just for children is definitely over (Keim et al.2005a,b). The increase in the number of adult patientsrequesting orthodontic treatment is also reflected inEuropean countries (Burgersdijk et al. 1991; Stenvik et al.1996; Kerosuo et al. 2000). Vanarsdall and Musich (1994)listed five reasons for this change. Three concerned theimproved capacity of the profession to treat problems inadult patients either only orthodontically or in combina tion with orthognathic surgery. Two points referred to thepatient’s desire to maintain their natural teeth.Proffit (2000) explained that the increase in the numberof adult patients seeking treatment was due to greater avail ability of information, and analyzed the motivation neces sary to seek orthodontic treatment as an adult. However,the patients referred to by Proffit are mostly well informedabout the possibilities and limitations of orthodontic treat ment, and while this assertion may be valid within certainsocioeconomic groups in the USA, it is rarely the case inAdult Orthodontics, First Edition. Edited by Birte Melsen. 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Published 2012 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd.Europe. A possible explanation of this difference betweenthe USA and Europe could be the marketing of orthodon tics in the USA. In Europe it is often ignorance and insecu rity that characterize the adult patients seen in theorthodontist’s office. Patients may come on their own ini tiative because they are dissatisfied with either the appear ance of their teeth or their ability to chew, or due to acombination of both, or they may have been referred bytheir family dentist.Who are the patients?How can we characterize the adult population presentingto an orthodontic office? Adult patients can be classifiedaccording to several criteria. While they all share the factthat they are no longer growing, we must differentiatebetween young adults, who have recently stopped growing,and older adults, who have experienced deterioration oftheir dentition and changes in their occlusion over time(Figs 1.1 and 1.2).Young adult patients are those who, from a professionalpoint of view, should have been treated earlier, or thosein whom optimal treatment can be carried out onlyafter cessation of growth. Based on the importance of theimpact of genetics on the final skeletal morphology (Savoyeet al. 1998), it is frequently considered desirable to post pone treatment of severe skeletal deviations that canbe recognized in other members of the family until adult hood, at which time surgical treatment can be carried out(Fig. 1.3).Some young adult patients with severe malocclusionsshould, however, have been treated earlier. Their malocclu sion, which was not considered as an indication for treat ment when younger, worsens with time and leads them to

2 Adult Orthodonticsseek treatment as adults (Figs 1.2 and 1.4). Proffit (2006)diagrammatically illustrated where tooth movement alonecan solve the problem, where tooth movements combinedwith growth modification is needed and where surgery isconsidered necessary. However, the lines indicating thelimits should not be considered as sharp cut-off points butrather as indicative of a ‘grey zone’ in which more than onetreatment option can be considered (Fig. 1.5). Cassidy et al.(1993) discussed making a decision about surgery based onthe advantages and disadvantages of surgical and ortho dontic approaches to the treatment of these patients. Onthe basis of analysis of post-treatment changes and a riskanalysis they concluded that conventional orthodontictreatment is a better choice in borderline cases.Surgery should not be a substitute for orthodontic treat ment but when treatment is delayed beyond the time whengrowth modification is possible, surgery is often the onlyFig. 1.3 Extraoral photograph of a young woman whose treatment waspostponed until adulthood as a surgical solution was foreseen. The malocclusion had worsened over puberty but since it was reflecting a family facialpattern, treatment was delayed until cessation of growth.Fig. 1.1 Classification of adult patients.(1)(2)Fig. 1.2 (1–3) An adult patient demonstrating a gradual increase in overjet over time.(3)

Potential Adult Orthodontic Patients(1)3(2)(4)(3)Fig. 1.4 (1–3) A slight increase in overjet which did not qualify for publicly funded treatment. The overjet increased over the years and a medial diastemadeveloped, leading to a more severe malocclusion. (4) In addition to the increased overjet there was extrusion of the upper incisors.possible solution. A lack of treatment at the most conven ient time thus adds to the number of surgical candidates.Another factor contributing to the increased demand fororthognathic surgery is the simplification of orthodontictechniques. The use of pre-adjusted brackets and the‘straightwire appliance’ (SWA) has certain limitations andmay contribute to the increased indication for orthognathicsurgery. When the available mechanics are limited to‘straight wires’ only, however, for patients in ‘grey zone’, themost suitable treatment option seems to be leaning moreand more towards surgery (Burstone 1991).Lack of availability or financial considerations may alsobe a reason for not having orthodontics at the optimal time.Third-party payments may have an impact on which chil dren will be offered orthodontic treatment and in severalcountries such as Denmark, the percentage of children whowill be offered conventional orthodontic treatment is polit ically determined. Orthodontic treatment will not be per formed if the severity of the malocclusion is below thecriteria established by law (National Board of Health 2003),and as a consequence the patient in Figure 1.4 might notbe offered treatment today either.Very few features of malocclusion reduce with time(Harris and Behrents 1988), with both Class II and ClassIII malocclusions becoming more severe (Fig. 1.6).Therefore, if a skeletal deviation which could have beenhandled by growth modification is left to worsen untilgrowth ceases, the only possible treatment may be a com bination of orthodontics and surgery. A reason, althoughnot acceptable, for the increase in the number of patientsreceiving orthognathic surgery is the fact that treatmentcomprising orthognathic surgery is frequently paid for by

4 Adult OrthodonticsFig. 1.6 Graphic illustration of the development of occlusion with age. Notethat the Class II and III malocclusions have worsened. (Redrawn from Harrisand Behrents 1988, with permission from Elsevier.)Fig. 1.5 Diagrammatic illustration of the changes in incisor position ingrowing and non-growing individuals that are possible with orthodontic toothmovement, growth adaptation and orthognathic surgery. The teeth in thecentre of the coordinate system illustrate the ideal position. The inner envelope of each diagram illustrates the possible correction that can be obtainedby tooth movements alone. It should be noted that the envelope is ellipticalin shape as the limits of movement in the labial and lingual direction are notthe same. Labial movement is easier in the maxilla and lingual movement iseasier in the mandible. The middle envelope indicates what can be achievedif orthodontic tooth movement is combined with growth modification. Theouter envelope indicates the possibilities of treatment when surgery is performed. (From Profitt [2006], with permission from Elsevier.)a third party, i.e. insurance or public funds. This has led toa preference for a surgical solution in borderline patientswho could be treated either with or without surgery. Thirdparty involvement in orthodontic services may thus resultin the unfortunate development of an increase in thenumber of adult patients needing treatment when the indi cation for treatment depends on the severity of the maloc clusion as based on static morphological criteria. Where thepercentage of children who can be offered publicly fundedtreatment is determined politically, the orthodontist hasonly limited freedom in determining how the resourcesavailable should be used in the most efficient way (NationalBoard of Health 2003). As a result, the orthodontist mayopt not to treat the most difficult cases but refer them tosurgery, thus shifting the responsibility for these cases toanother part of the health service. Excessive tightening ofthe criteria for reimbursing treatment costs may thereforeincrease rather than reduce the total costs for the ‘thirdparty’ in the long run (Mavreas and Melsen 1995).Older adult patients, over age 40, present with signs ofageing, deterioration or a dentition often characterized byextensive rehabilitation (Proffit 2000). The number of thesepatients is also increasing and the patients often presentwith a ‘secondary malocclusion’, i.e. malocclusion that hasdeveloped or has worsened in adulthood. This may occur asa result of deterioration of the dentition and th

Does an Invisalign treatment plan differ from a regular orthodontic treatment plan? 344 How does one take an adequate impression for the Invisalign System? 344 What is required to be evaluated in ClinCheck ? 345 What material ar