Transcription

Order duplication and liquiditymeasurement in EU equity marketsESMA Economic ReportNo. 1, 2016

ESMA Economic ReportNo. 1, 20162ESMA Economic Report, Number 1, 2016Contributors: Carlos Aparicio Roqueiro, Claudia Guagliano, Cyrille Guillaumie, Steffen Nauhaus, Christian Winkler, SteffenKern.Acknowledgements: We thank the members of the CEMA HFT Task Force, namely Annemarie Pidgeon, Bas Verschoor, CarlaCabrita, Carla Ysusi, Carole Gresse, Christophe Majois, Felix Suntheim, Giovanni Siciliano, Julien Leprun, Kheira Benhami,Luc Goupil, Marc Ponsen, Nicolas Megarbane, Ramiro Losada, Richard Payne, Hans Degryse, Rudy de Winne, Sander vanVeldhuizen, Thorsten Freihube, Valeria Caivano, Victor Mendes for helpful suggestions. We are grateful to Antoine Bouveretfor his early leadership of this research project, his conceptual input, as well as his valuable comments.Authorisation: This Report has been reviewed by ESMA’s Committee for Economic and Market Analysis (CEMA) and has beenapproved by the Authority’s Board of Supervisors. European Securities and Markets Authority, Paris, 2016. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translatedprovided the source is cited adequately. Legal reference of this Report: Regulation (EU) No 1095/2010 of the EuropeanParliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 establishing a European Supervisory Authority (European Securities andMarkets Authority), amending Decision No 716/2009/EC and repealing Commission Decision 2009/77/EC, Article 32“Assessment of market developments”, 1. “The Authority shall monitor and assess market developments in the area of itscompetence and, where necessary, inform the European Supervisory Authority (European Banking Authority), and theEuropean Supervisory Authority (European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority), the ESRB and the EuropeanParliament, the Council and the Commission about the relevant micro-prudential trends, potential risks and vulnerabilities. TheAuthority shall include in its assessments an economic analysis of the markets in which financial market participants operate,and an assessment of the impact of potential market developments on such financial market participants.”European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA)Economics and Financial Stability Unit103, Rue de GrenelleFR–75007 Parisrisk.analysis@esma.europa.eu

ESMA Economic ReportNo. 1, 20163Table of contentsExecutive summary. 4Introduction . 5Literature review. 7Dataset description . 10Identifying high-frequency trading – the key results of ESMA (2014) . 12The extent of order duplication in EU equity markets . 14The behaviour of trade participants . 17Impact of trading on gross and net liquidity . 18Conclusion . 23References . 25Annex 1: Sample characteristics . 27Annex 2: Impact of trading on gross and net liquidity- additional results . 29

ESMA Economic ReportNo. 1, 20164Executive summaryThis report is the second part of ESMA’s high-frequency trading (HFT) research. The starting point forboth reports is the change in the trading landscape of equity markets over the last decade. Thedefining features of this change are increased competition between trading venues, fragmentation oftrading of the same financial instruments across EU venues and the increased use of fast andautomated trading technologies. In our first report we analysed the extent of HFT activity across theEU in such an environment using a novel identification method for HFT activity. We found that HFTactivity represents between 24% and 43% of value traded and between 58% and 76% of orders in oursample.1 In this report we focus on liquidity measurement where equity trading is fragmented.In an environment characterised by competition between trading venues, traders do not always knowon which venue they will be able to trade. They may “advertise” their intention to trade by postingsimilar orders on more than one trading venue at the same time (“duplicated orders”). This, however,leads to the risk of trading more shares than wanted. Therefore some traders may immediately cancelunmatched duplicated orders on other venues after one of their duplicated orders has been filled.Using the HFT identification method developed in our first report, we find evidence for this tradingpattern. 20% of the orders in our sample are duplicated orders and in 24% of trades the traderimmediately cancels unmatched duplicated orders. We believe that duplication of orders andimmediate cancellation of duplicates after a trade has become part of the strategy to ensure executionin fragmented markets, e.g. for market makers or where institutional investors are searching forliquidity. However, we show that taking duplicated orders into account when measuring liquidity leadsto overestimation of available liquidity in fragmented markets.The proportion of duplicated orders varies with the type of traders, the market capitalisation of theunderlying stock and the fragmentation of trading in a stock. As expected, duplicated orders are moreprevalent for HFTs (34% of orders) than for non-HFTs (12% of orders). They account for 22% oforders in large cap stocks compared to 12% of orders in small cap stocks. Also, fragmentation oftrading is positively correlated with order duplication. We find 13% of duplicated orders for stocks withlow trading fragmentation and 23% for high fragmentation.Regarding the extent to which duplicated orders are immediately cancelled after trades (and thussubsequently are not available to the market), we carry out a number of analyses. First, we find thatfor 24% of all trades, the trader on the passive side of the trade immediately cancels order duplicatesafter the trade. This proportion is higher for HFTs (28%), large cap stocks (27%) and where trading ismore fragmented (31%). Second, we look at the different reaction of two measures of liquidity: grossliquidity, the aggregated volume of displayed orders across multiple markets, and net liquidity, whichdeducts duplicated orders from the gross liquidity measure. We compare these two measures toestablish whether order duplication should be taken into account when measuring liquidity infragmented markets. A stronger fall of the gross liquidity measure after trades compared to the netliquidity measure is an additional indication that a proportion of duplicated orders is indeedimmediately cancelled after trades and thus not available to the market. Our descriptive andeconometric analyses confirm this hypothesis.Both in our first HFT report and in this report we use unique data collected by ESMA, covering asample of 100 stocks on 12 trading venues in nine EU countries for May 2013. Our data allow us toidentify market participants’ actions across different venues. Thus we are able to complement theliterature, as most of the HFT studies published so far focus either on the US or on a single countrywithin Europe and few are able to analyse the behaviour of market participants across trading venues.Previous studies have found evidence supporting that fragmentation of trading increases liquidity inequity markets. Our analysis qualifies these results, as using data that allow us to identify marketparticipants’ actions across different venues, we find a substantial extent of order duplication infragmented markets. It is important to state that unless they are successfully cancelled, duplicatedorders are available to the market and all of them can be matched. However we find that a substantialproportion of order duplicates are immediately cancelled after a trade occurs and thus subsequentlynot available to the market. From an analytic perspective, our findings suggest that to avoidoverestimation of available liquidity duplicated orders should be taken into account when measuringliquidity in fragmented markets, for example with our net liquidity files/library/2015/11/esma20141 - hft activity in eu equity markets.pdf

ESMA Economic ReportNo. 1, 2016IntroductionIn recent years, financial markets have undergonea series of significant changes. Regulatorydevelopments, technological innovation andgrowing competition have increased theopportunities to employ innovative infrastructuresand trading practices.On the regulatory side, the entry into force of theMarket in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID)in 2007 has re-shaped markets in the EU.Simultaneously,developmentsinnewtechnologies have enabled the use of automatedand very fast trading technologies.2 The resultingtrading landscape can be characterised by highercompetition between trading venues, thefragmentation of trading in the same financialinstruments across venues in the EU, as well asthe increased use of fast and automated tradingtechnologies.It has been suggested that the order books ofexchanges are today less informative thanpreviously since liquidity is more transitory or “lesscertain”, as in fragmented markets it is not easy toanticipate where potential counterparties will tradenext, or if they are active only on one venue or onmultiple venues. Lescourret and Moinas (2015)analyse liquidity supply in fragmented financialmarkets and find that ex ante fragmentation maydecrease total transaction costs (a measure ofmarket liquidity): The possibility to compete in asingle venue forces in some cases competitors topost aggressive quotes across all venues.In this context, the disparity in terms of speed andtechnology between ordinary traders and highfrequency traders (HFTs) has become significant.Investment in fast trading technology ion (Biais et al, 2015). Thus,fragmentation may be more likely to attract HFTs,as they are able to implement cross-venuearbitrage strategies.At the same time, recent events of short-termliquidity shortages and sudden spikes of volatilityacross market segments have triggered questionsrelated to the impact of HFT on volatility, liquidityand, more generally, market quality.When it comes to analysing the impact of HFTactivity the operational definition of HFT becomescrucial. In general, total trading activity can bedivided into algorithmic trading (AT) and non-2See e.g. Lo (2016) for an overview of technologicalchange in finance.5algorithmic trading, depending on whether or notmarket participants use algorithms to make tradingdecisions without human intervention. Kirilenkoand Lo (2013), for example, describe AT as “theuse of mathematical models, computers, andtelecommunications networks to automate thebuying and selling of financial securities”.3Following definitions proposed in the literature,HFT is a subset of AT and has the followingfeatures— proprietary trading;— very short holding periods;— submission of a large number of orders thatare cancelled shortly after submission;— neutral positions at the end of a trading day;and— use of colocation and proximity services tominimise latency.From an analytical perspective, the absence of aunique definition makes it difficult to achieve aprecise identification of HFT activity. The literatureemploys a number of approaches to identify HFTactivity. None of these approaches is able toexactly capture HFT activities and they lead towidely differing levels of HFT activity. In 2014,ESMA published a report discussing theidentification of HFT and providing estimates ofHFT activity based on a cross-EU sample ofstocks. The report, using unique data collected byESMA covering a sample of 100 stocks from 9 EUcountries and 12 trading venues for May 2013,shed further light on the extent of HFT in EU equitymarkets. The report provided a lower and an upperbound for HFT activity, employing two mainmethodologies:a) direct approach: an institution based measure(each institution is either HFT or not) focusingon the primary business of firms (lowerbound), and3A legal definition of algorithmic trading is provided byMiFID II. Article 4(1)(39) of MiFID II states thatalgorithmic trading “means trading in financialinstruments where a computer algorithm automaticallydetermines individual parameters of orders such aswhether to initiate the order, the timing, price or quantityof the order or how to manage the order after itssubmission, with limited or no human intervention, anddoes not include any system that is only used for thepurpose of routing orders to one or more trading venuesor for the processing of orders involving nodetermination of any trading parameters or for theconfirmation of orders or the post-trade processing ofexecuted transactions”. uri CELEX:32014L0065&from EN

ESMA Economic ReportNo. 1, 20166b) indirect approach: a stock-based measure (aninstitution may be HFT for one stock but notfor another one) focusing on the lifetime oforders (upper bound).4Chordia et al (2013) write: “There is growingunease on the part of some market observers that[ ] violent price moves are occurring more oftenin financial instruments in which HFTs are active.”In the analysed sample, HFT activity accounts for24% of value traded using the direct approach,and 43% using the lifetime of orders approach. Forthe number of trades the corresponding numbersfor HFT activity are 30% and 49%, and for thenumber of orders 58% and 76%. Overall, thesedifferences show that, depending on theidentification approach chosen, the estimated levelof HFT activity varies significantly thoughremaining relevant for EU equity markets (C.1).More recent research qualifies some of thepositive findings. While Boehmer et al (2015) findthat AT on average increases market quality, butalso increases volatility, they also find that ATreduces the market quality and leads to a strongerincrease in volatility of small stocks. Bongaerts andVan Achter (2016) argue that the combination ofspeed technology and information processingtechnology can lead to the implementation ofinefficient speed technology, endogenous entrybarriers and rents. This can result in liquidityevaporating when it is most needed. Chakrabartyet al (2016) carry out analysis during a time ofmarket stress. They analyse market quality on theSpanish Stock Exchange (SSE) from thebeginning of 2010 to the end of 2013. Two eventscoincide: On the one hand, short sellingrestrictions were in place on the SSE from 11August 2011 to 15 February 2012 (for financialsector stocks) and from 23 July 2012 to 31January 2013 (for all stocks). On the other hand,the SSE introduced technological changes toattract HFTs. A smart trading platform wasintroduced in April 2012 (where no short sellingrestrictions were in place), HFT activity increasedafterwards. Colocation was introduced inNovember 2012 (during the second short sellingban); here HFT activity did not increaseafterwards. Following technological changes,liquidity and price efficiency deteriorated.C.1HFT activity – Overall results for the HFT flag and lifetime oforders approachesHFTflagValue tradedNumber oftradesNumber ofordersLifetime of ordersTotalTotalThereof investmentbanks244322304923587619Note: Figures are weighted by value of trades (value traded), number oftrades and number of orders, in %.Source: ESMA.The observation that HFT provides for a large partof activity in equity and other financial marketsraised the question of the impact of HFT activity onthese markets.One first general question is related to the effect ofHFT on market quality. Research generally foundthat HFTs improve traditional market qualitymeasures: Hasbrouck and Saar (2013) find thatHFT is related to decreasing spreads, increasingdisplayed depth in limit order book and loweringshort-term volatility in US equity markets. Malinovaet al (2014) using a different sample also concludethat HFT activity is associated with improvedmarket quality (mainly measured by tighter bid-askspreads) while Brogaard et al (2014 and 2016)underline the positive impact of HFT on priceefficiency. Despite these findings, many investorsare concerned that HFT liquidity provision isselective and limited to periods of low stress.54A similar approach is used by Bellia et al. (2016) whofind that traders generally exhibit different types ofbehaviour across stocks and over time. Therefore, theyconclude that the usual characterisation of a traderacting as HFT, for all time and for all stocks, is likely tobe invalid.5Korajzcyk and Murphy (2015) find that HFTs do provideliquidity for institutional trades, but to a significantlysmaller extent when trades are stressful, i.e.comparatively large. Bongaerts and Van Achter (2016)Another strand of the literature focuses on the bestmarket design in presence of HFT. Budish et al(2015) argue that the high-frequency trading armsrace is a symptom of flawed market design andthat financial exchanges should use frequent batchauctions.6 The batch auctions system processesorders received during a fixed time intervalsimultaneously, thus treating concurrently orderssubmitted by faster traders with those by slowerdescribe mechanisms where HFT activity can reduce orlead to the evaporation of liquidity.6Bongaerts et al (2016) analyse in a theoretical model thelikelihood of arms race behaviour in markets withliquidity provision by HFTs. Liquidity providers (makers)and liquidity consumers (takers) make costlyinvestments in monitoring speed. They highlight twoopposing economic channels that influence such effectin partially offsetting ways. Competition among makersand among takers may indeed trigger an arms race inthe classic sense. However, complementarity betweenthe two sides, the increased success rate of trading, mayoffset this effect if the gains from trade are large enough.Therefore, the likelihood of arms races depends on howgains from trade depend on transaction frequency.

ESMA Economic ReportNo. 1, 2016traders and reducing the benefit of marginalsuperiority in speed.Other researchers argue that HFTs are aheterogeneous group and they employ a variety ofstrategies, with different impact on financialmarkets. Menkveld (2013) focuses on just oneHFT following a market making strategy andshowsthe relationshipbetween marketfragmentation and HFT in current financialmarkets. Indeed, he shows how the HFT entry intoa large incumbent market NYSE-Euronext and theentrant market Chi-X at the same time not onlyfragmented trading, but it also coincided with a50% drop in the bid-ask spread. Hagstromer andNorden (2013) distinguish between HFTs followingmarket making strategies and others followingopportunistic strategies and show that the latterare associated with increases in volatility, whereasthe former are associated with decreases involatility.One of the concerns often mentioned with respectto HFTs is that they overload the exchanges withsubmissions and cancellations of limit orders,7even though this strategy can be essential incurrent fragmented market.In this report we focus exclusively on the presenceof duplicated orders across multiple venues andhow this may affect the accurate measurement ofgenuine liquidity and thus the accurateunderstanding of liquidity dynamics.We define duplicated orders as those posted onthe same side of the order book, at the same priceand by the same market agent but on differentvenues. Our hypothesis is that order duplication ispartially explained by the search for counterpartiesin fragmented markets8 and that, once the tradingobjective has been fulfilled in one venue, in manycases the liquidity will be immediately removedfrom the other venues. Such a strategy requiresfast reaction, thus it is likely that mostly HFTs areable to act in this way. This fast disappearance oforders will have an impact on observed marketliquidity. The SEC’s Concept Release on EquityMarket Structure (2010) recognised theimportance of high frequency quoting in that itmight represent “phantom liquidity (which)disappears when most needed by long-terminvestors”. If this is the case, a liquidity measurethat takes account of the existence and the extent7See Egginton et al (2014), Friedrich and Payne (2015)for more analysis on the impact of quote stuffing andhigh order-to trade-ratios on financial markets.8See AFM (2016) for a discussion based on interviewswith market participants (HFT and buy-side firms as wellas trading venues).7of order duplication should be more accurate thana gross measure of liquidity that does not controlfor order duplication.9 Conrad et al (2015) describethe disadvantage characterising most of theliterature focusing on a single stock exchange: In afragmented market it is entirely possible that HFTbehaviour in one market may not reflect aggregatemarket behaviour.10 Our unique dataset allows usto avoid this disadvantage.The structure of the paper is as follows. First, weprovide an overview of the existing literature onthe impact of HFT activity and fragmentation onliquidity in financial markets. Second, wedescribe our unique dataset. Then, we introducethe duplicated orders metric which is based onthe concepts of gross and net liquidity.We also analyse the behaviour of the differenttraders performing the order duplication strategyafter the execution of trades for which theyprovided liquidity. We then look at the extent andthe relevance of order duplication in EU equitymarkets, in particular for HFTs. Finally, weanalyse the relevance of order duplication forliquidity measurement in fragmented equitymarkets. We carry out descriptive andeconometric analyses comparing the behaviourof the gross and net liquidity measures aftertrades occur in the market. This enables us toprovide indications regarding the extent to whichduplicated orders are not available to the marketafter trades and thus traditional liquiditymeasures based on gross liquidity mayoverestimate available liquidity in fragmentedequity markets.Literature reviewThere is a large body of literature scrutinizingthe activity, behaviour and impact of HFTfirms.11 Based on various market quality metrics,there is mixed evidence on the question whetherHFT activity has been beneficial to financialmarkets. Most notably, HFT is associated withtighter bid-ask spreads (Hendershott, et al,2011; Malinova et al, 2013), and more efficient9See AFM (2016).10For instance, a high frequency trader may extractliquidity from Exchange X (which is known to be cheaperfor extracting liquidity for a particular group of stocks) butmay be providing liquidity in Exchange Y: research onlyobserving trades on Exchange X would erroneouslyconclude that this high frequency trader is a liquidityextractor.11For an extensive review of the literature on HFT see e.g.SEC (2014).

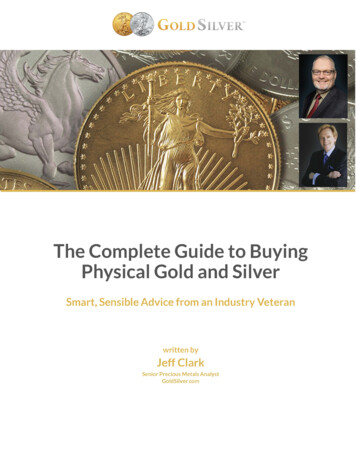

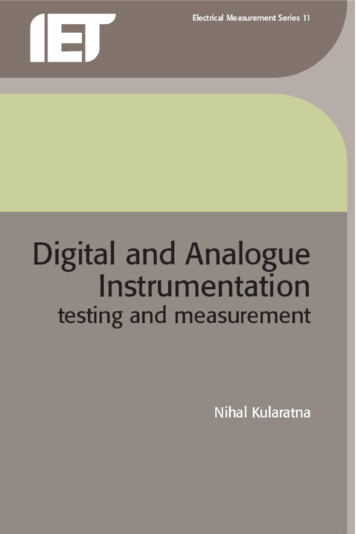

ESMA Economic ReportNo. 1, 2016price formation (Brogaard et al, 2014). However,this may not hold under all market conditions.Breckenfelder (2013) finds that in situationswhere HFTs compete for trades liquiditydecreases and short-term volatility rises.Boehmer et al (2015) find that AT on averageincreases market quality, but also increasesvolatility, they also find that AT reduces the marketquality and leads to a stronger increase in volatilityof small stocks. Results with regard to volatilityare found to vary between market makers andaggressive HFTs, where the latter areassociated with increases in volatility and viceversa for the former (Benos and Sagade, 2016;Hagströmer and Norden, 2013). Aquilina andYsusi (2016), using orders and trades data on120 UK stocks from the main UK lit venues,address the question whether HFTs can predictwhen orders are going to arrive at differenttrading venues and trade in advance of slowertraders. They find no evidence that HFTs in theUK are able to systematically anticipate nearsimultaneous orders sent by non-HFTs todifferent trading venues and thus making riskfree profits due to their latency advantages.When looking at longer time periods (seconds ortens of seconds), they find patterns consistentwith HFTs anticipating the order flow of nonHFTs. For these longer time periods theyhowever could not conclude whether this isbecause HFTs can in fact anticipate the orderflow or whether they are faster to react to newinformation.A limitation of most publications to date is thatthey rely on data covering a single trading venueeither in the US, Canada or in a single countrywithin Europe. Results based on data from aparticular trading venue may not necessarilyhold on other venues or when a cross-venueanalysis is carried out.12 Only few studies usecross-venue data. Exemptions are e.g. Boehmeret al (2016) who analyse trading activity of HFTfirms across all Canadian trading venues andBaron et al (2016) who use regulatorytransaction data to analyse HFT activity acrossvenues for most stocks in the Swedish OMX30index.Our study complements the HFT literature bylooking at equity trading across 9 EU countriesand 12 trading venues. Further, we are able toidentify the same trader’s activity on multiplevenues. This allows having a clearer picture ofHFT behaviour in fragmented markets.The trading landscape that investors face todayhas grown to be increasingly fragmented. Angelet al (2011) note that the market share of theNYSE in equity trading has decreased from 80percent in 2003 to just 25.8 percent in 2009. Asmuch of the literature analyses only a limitednumber of trading venues, the liquidity studied isonly a subset of the actual liquidity available toinvestors. In Europe, the intensity of thefragmentationprocesshassignificantlyincreased since the adoption of MiFID. Theshare of trading on multilateral trading facilities(MTF) was close to zero at the beginning of2008, while at the beginning of 2011 it wasequal to 18% of total turnover (Fioravanti andGentile, 2011). For our sample period in May2013, the share of turnover of new venues hadreached 28% of trading in electronic order booksand 22% of total equity trading, according todata from the Federation of European SecuritiesExchange. The level of fragmentation of EUnational indices has remained broadly stablesince 2013 (C.2).C.2European equity markets - Fragmentation0.80.60.4See Conrad et al (2015) for a description of this issue.Sample period0.20Jan-10Dec-10Nov-11Oct-12 Sep-13FragmentationAug-14Jul-15Note: Median value of the trading fragmentation of selected national indicesmeasured as (1-Herfindahl-Hirschman index), monthly average. Included indicesare AEX, BEL20, CAC40, DAX, FTSE100, MIB, IBEX35, ISEQ20 and PSI20.Sources: BATS, ESMA.Only a small number of studies analyses theimpact of HFT on liquidity in the context offragmentedmarkets.Themajorityofpublications consider the effect of fragmentationon market quality, with some nuances about ATactivity by use of a proxy.13Biais et al (2015) find in a theoretical work thatinvestment in fast trading technology ion. To the extent that this enhancestheir ability to reap mutual gains from trade, itimproves social welfare. On the other hand, fast13128The data underlying those publications considered heredoes not identify individual traders and does thus notallow for direct or indirect identification of HFT firms.

ESMA Economic ReportNo. 1, 2016institutions observe value relevant informationbefore slow ones, which creates adverseselection. Thus, investment in fast tradinggenerates negative externalities, which are notinternalised by financial institutions andtherefore are detrimental to social welfare.In Van Kervel (2015) market quality is found tobe improved as a result of increased marketfragmentation, but there is evidence that orderduplication may bias traditional measures ofliquidity. Holden and Jacobsen (2014) highlighthow cancelled orders in current fast, competitivemarket contribute to increased difficulties andbiases of liquidity measurement.Degryse et al (2014) study the effect of darktrading and fragmentation on market quality.Using order book data for 51 Dutch stocks forseveral lit and dark markets14, their findingsindicate that lit fragmentation improves liquidityaggregated over all visible trading venues.However, liquidity is lowered in the traditionalmarket. This suggests that the benefits offragmentation are not enjoyed by investors whosend orders only to the traditional market.Aitken et al (2015) provide evidence using USdata on listed Nasdaq securities. Employing asimultaneous equations model, they find thatfragmentation of the lit market order flow, withthe ensuing increase in competition, particularlyfrom HFT and AT firms, has been largelybeneficial for financial markets. Effectivespreads and end-of-day manipulation both fellas a result of increased fragmentation. Similar toDegryse et al (2014), the effect of dark marketfragmentation was found to be detrimental.O’Hara and Ye (2011) focus on the impact ofmarket fragmentation on market quality for USstocks, using data covering 150 Nasdaq stocksand 112 NYSE stocks. Their findings indicatethat fragmentation is largely beneficial to marketquality in various respects. More fragmentedstocks have lower transaction costs in terms ofeffective spreads, and faster execution speeds.Small stocks are particular beneficiaries fromthis effect. While short-term volatility was foundto increase with fragmentation, overall priceeffici

Identifying high-frequency trading . It has been suggested that the order books of . technology between ordinary traders and high-frequency traders (HFTs) has become significant. Investment in fast trading tec