Transcription

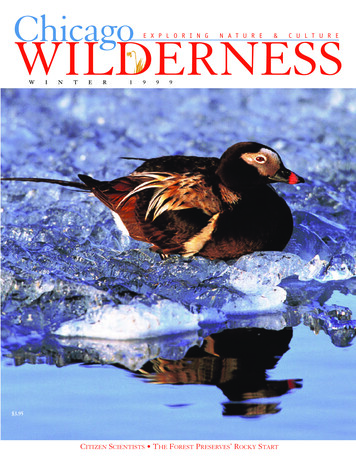

ChicagoE X P L O R I N GN A T U R E&C U L T U R EWILDERNESSWINTER1999 3.95CITIZEN SCIENTISTS THE FOREST PRESERVES’ ROCKY START

What is Chicago Wilderness?Chicago Wilderness is some of the finest and mostsignificant nature in the temperate world, with roughly200,000 acres of protected natural lands harboringnative plant and animal communities that are morerare—and their survival more globally threatened—than the tropical rain forests.C H I C A G OW I L D E R N E S Sis an unprece-dented alliance of 76 public and private organizationsworking together to study and restore, protect andmanage the precious natural resources of the Chicagoregion for the benefit of the public.ChicagoWILDERNESS is a quarterly magazine that celebrates the rich biodiversity of this region and tells theinspiring stories of the people and organizations working to heal and protect local nature.

C H I C A G OW I L D E R N E S SA R e g i o n a l N a t u re R e s e r v eFriends of NatureTDebrawildflowers were disappearing from sites, not because theywere being plucked but because their habitat was suffering.Once open areas, pleasant for strolling, picnicking or providing respite for the eye, were gradually becoming chokedwith invasive brush.Yet ours is a continuing historyof civic pride and action onbehalf of nature. Soon all theregion’s counties would have preserve districts of various kinds.The spirit of Perkins, Jensen, MayWatts, and others lives on in theefforts to restore natural areas andin the collaborative conservationinitiatives of Chicago Wilderness.Today, I suspect, we hallownature no less than Perkins,Jensen, and Watts, but, perhaps,we respect nature more. We havelearned what a challenge it is notonly to protect tracts of land, butalso to preserve healthy complexes of species—the wholecommunities called marshes,prairies, savannas and woods—that constitute our nativelandscape.Those among us today whohave the fortitude, vision, andpersistence of the forest preservefounders will be the conservation heroes generations hence.These are the people of Chicago Wilderness, the citizenscientists profiled in this issue, the leaders of organizationslarge and small (such as Charlotte and Herbert Read andDr. George Rabb, pp. 21-23), and not least of all, you, ourreaders. Bless you—and keep the faith.Lantern slide: Forest Preserve District of Cook CountyOPPOSITE: Rob Curtis/The Early Birderhe stirring and a cautionary tale of the battle to establish the Forest Preserve District of Cook County beginson page 4. When Dwight Perkins and Jens Jensen set aboutsaving “natural park lands” for the benefit of people, theydid not know these holdingswould become refugia for rare andendangered species, harboring biodiversity of global conservationsignificance.They were establishing culture.Along with their friend and colleague Jane Addams, they wereconcerned for the health and welfare of urban residents—the wageearners, as they put it—whodeserved, in their view, pleasantnatural areas to enjoy, find inspiration, and cultivate a bond withthe natural heritage of the region.At the time, they thought protecting and preserving naturemeant simply saving land fromdevelopment. Everyone did.The new Forest Preserve District purchased its first land, 500acres of Deer Grove, on June 25,1916. They called it a “preserve,”campaigned in sometimes charming ways to protect its nature, putout fires, and essentially left thelands alone. (The young lady appearing on the back cover ofthis issue was part of an early campaign to educate visitorsnot to pick the wildflowers.)But these quaint values were not enough. Many of theplaces Perkins fought so hard to preserve became less attractive over the years, to both nature and people. WoodlandS ho reE D I T O RWINTER 1999

ONTENTPhoto: Forest Preserve District of Cook CountyCSF E AT U R E S4TO PRESERVE AND PROTECT: The Origins of the Forest Preservesby Stephen F. Christy, Jr. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4The noble and little-known history of the nation’s first forestpreserve district.D EPA R T ME N T SPhoto: Kathy RichlandTHE AMATEUR AND THE PRO: Science at the Grass Rootsby Sheryl DeVore . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Citizen scientists—noodling around in nature and making a realcontribution.9Into the Wild. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Photo: Morton Arboretum ArchivesWhere to go.What to do.How to help.Natural Events Calendar.Meet Your Neighbors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Meet the sleek elusive mink. Meet Charlotte and Herb Read,savers of the dunes. Meet Dr. George Rabb, conservationambassador from the Brookfield Zoo.24Local Heroes: Remembering May Watts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24She signed her poems “Face the Wind.” She inspired legions ofnature lovers. Get to know a local hero.News from Chicago Wilderness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Return of a Native: Whooping Big Bird Story . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28Reading Pictures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32The Unseen.ChicagoWILDERNESSVolume II, Number 2BOARD OF DIRECTORS:President: Dr. George RabbVice-President: Dan GriffinSecretary: Laura GatesTreasurer: Barbara Whitney CarrJerry Adelmann, Laura Hohnhold, John Rogner, Ron WolkE D I T O R . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Debra ShoreS E N I O R E D I T O R . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Stephen PackardASSISTANT EDITORS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Sheryl De Vore. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Chris HowesNEWS EDITOR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Elizabeth SandersART DIRECTOR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Liita ForsythASSISTANT DESIGNER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Terri WymoreE D I T O R I A L C O N S U LTA N T . . . . . . . . . Bill AldrichABOVE AND COVER: Old squaw ducks can be seen, sometimes by the hundreds, from the bluffsoverlooking Lake Michigan. Before they return to the Arctic to enjoy breeding, their black and whitepattern changes dramatically, nearly reversing intelf (see cover). Photo above by Jim Flynn/RootResources. Cover photo by Art Morris/Birds as Art.OPPOSITE: Bur oak presides over snowy savanna along Flint Creek near Barrington, Illinois.Photo by Donna Lee.WINTER 1999Chicago WILDERNESS is published quarterly.Subscriptions are 12/yr. Please address all subscriptioncorrespondence to Chicago WILDERNESS, P.O. Box 268,Downers Grove, IL 60515-0268. Please direct editorialinquiries and correspondence to Editor, Chicago WILDERNESS, 9232 Avers Ave, Evanston, IL 60203. (847) 6772470. e-mail: cwmag@suba.com Unsolicited manuscriptscannot be returned without a self-addressed stamped envelope. Chicago WILDERNESS is printed on recycled paperand should be passed around from friend to friend. ChicagoWILDERNESS is endorsed by the Chicago Region Biodiversity Council. The opinions expressed in these pages,however, are the authors’ own. by Chicago WildernessMagazine, Inc.ISSN 1097-8917. Postmaster, address service requested toChicago WILDERNESS, PO Box 268, Downers Grove, IL60515-0268.All rights reserved.3

To Preserveand Protect by Stephen F. Christy, Jr.Do Forest Preserves face challenges today?Just look at what they overcame to get started.Our northeastern Illinois forest preserves total morethan 100,000 acres and represent the largest tractof locally-owned public conservation land in thenation. Their benefits for our environment, recreation andeducation are incalculable, and they preserve much ofChicago’s natural charm which, without their existence,would certainly have been lost to the area’s growth.Of the millions of users of our Forest Preserves today fewwould believe it took more than 20 years for the dream ofthe preservation of these lands to become a reality. This4magnificent civic accomplishment came about largelythrough the determined efforts of two great Chicagoans:the architect Dwight Perkins (1867-1941), best remembered today for his visionary designs of many of Chicago’spublic schools, and the landscape architect Jens Jensen(1860-1951), nationally known for his park designs inChicago and other cities and a life-long champion of conserving America’s landscape. Perkins was level-headed,thorough, and methodical, while Jensen was an outspoken,emotional, and charismatic leader. Together they made aCHICAGO WILDERNESS

good team for the long work ahead.As early as 1894 Jensen, from his frequent local wanderings, had sketched a map of lands then far-distant fromChicago that he felt should be preserved for future generations. Perkins himself was constantly urging people to lookahead on Chicago’s growth, astounding people in 1902 byclaiming:“Chicago will be a city of 10,000,000 inhabitants withinthe next 50 years, and when we are planning for the city’sfuture we must take pains not to be so short-sighted as tooverlook it. We have a right to dream — if we are wideawake when we do it.”In 1899 a civic group known as the Municipal ScienceClub, of which Jensen and Perkins were members, began astudy of Chicago’s current parks and playgrounds. TheClub’s report led to the Chicago City Council establishingin 1901 a Special Park Commission having a membership ofJensen, Perkins, and other civic leaders as well as aldermenand park commissioners. The report they prepared said, “Inthe rapid growth of Chicago north, west, and south, thicklysettled communities are approaching natural park territoryand other extensive open areas which are suitable park sitesand could be improved without a great expenditure ofmoney before the rapid march of commercial interests andbefore suburban settlements efface the beauties of natureand destroy the usefulness of these spaces for parks.”As with most novel ideas, this statement had precedentto lend it strength. The Boston landscape architect,Charles Eliot, had convinced that city to set aside 10,000“In the rapid growth of Chicago north,west, and south, thickly settled communities are approaching natural parkterritory and other extensive open areaswhich are suitable park sites ”acres of outer parks during the 1890s, providing Bostonwith a total open space system then unsurpassed in thenation. Perkins’ wife Lucy, a writer and artist, visitedBoston and found this system “ so arranged that parksare accessible from all parts of the city, and it is difficultto think of any Boston child as shut away from the beauties of nature.”So well-received were the Special Park Commission’srecommendations that in 1903 Cook County Board Chairman Henry Foreman formed the Outer Belt ParkCommission and charged it with “the creation of an outerbelt of parks and boulevards encircling Chicago.” At thesame time the Special Park Commission, seeing that itsconcerns for playgrounds and inner-city parks were well onthe way to solution, turned to the larger question of theWINTER 1999PERKINS:level-headed,thorough,and methodical;JENSEN:outspoken, emotional,and charismatic a good team for the work ahead.outer parks. These efforts culminated in 1904 with Foreman’s publication of The Outer Belt of Forest Preserves andParkways for Chicago and Cook County. This publication,edited by Perkins and having a lengthy section by Jensendescribing the proposed lands, stands today as the culmination of a decade of diligent groundwork by these two menas well as a classic document from Chicago’s great age ofcivic improvement. Contributing to it also were other wellknown civic figures, such as Foreman; landscape architectOssian Simonds, designer of Graceland Cemetery; meatpacker Oscar Mayer; and University of Chicago sociologistCharles Zueblin.Perkins first dealt with the lack of open space inChicago, concluding that past city growth revealed largelyan “enormous waste of treasure, time, and human life dueto the lack of forethought and confidence in the city whenit was originally planned.”The Commission’s report went on to advocate in detailthe preservation of those lands which, for many years, hadbeen recognized as “naturally beautiful”: a crescent surrounding Chicago, starting at the north in the Skokie andNorth Branch valleys, passing west of the city along theDes Plaines River, and turning east along the Sag valley toLake Calumet after embracing the highlands of the Palos.The second half of the report, written by Jensen, dealt ingreater detail with, as he called it, “the movement foracquisition of large forest park areas.” He reiterated threegreat reasons for this enterprise: preserve for present and future generations lands of natural scenic beauty situated within easy reach of themultitudes that have access to no other grounds forrecreation or summer outings;5

Forest Preserve founders were struck by the open structure of oak forests, calling them “natural parks.” preserve spots having relation to the early settlements ofChicago which are therefore of historical importance;and, preserve flora in its primeval state for the sake of thebeauty of the forest and for the benefit of those desiringknowledge of the plants indigenous there.“ the woodlands should be broughtwithin easy reach of all people,especially the wage earners.”Jensen then followed with a detailed account of the history of Chicago’s native landscape and the specialsignificance of each recommended area.The report was a masterpiece of landscape planning.Based on the then-current beliefs best articulated by landscape architect and planner Frederick Law Olmsted that“rural life has the effect of countering a certain impressionof town life,” bolstered by exhaustive study of other cities’progress, and steeped in a thorough knowledge of Chicago’snative landscape and a passionate hope for the city’s future,it opened many eyes. The 3,000 original copies were distributed in a matter of months, yet 12 years would passbefore the first acre of land was set aside.The trouble began in 1905. Foreman’s Special Park6Commission decided a bill to protect these lands must passat once, noting how rapidly land values were rising. AnAct was thus hastily rammed through the state legislature,one viewed by many supporters as favoring certain politicalinterests at the expense of the overall plan. Incidentally,the term “forest preserve” first appeared in this bill coinednot so much to emphasize protecting woods but to avoidaccusations of double taxation with existing park districts.Jensen and Perkins led wildland tours to teach city folk aboutnature and to build constituency.CHICAGO WILDERNESS

The Special Park Commission and other civic groupsopposed this bill, arguing that it would place the administration of the forest preserves in state hands and that therewere no provisions for connecting the forest preserves asthe original plans had called for.Nevertheless, Illinois Governor Deneen signed the bill,and it was presented to referendum in November of 1905where a public favorable to the general idea but unaware ofthe political machinations behind the bill, passed it. Dismayed, Perkins and his followers prepared to go to court onthe grounds that a true majority of voters had not favoredthe bill. Sensing trouble, Governor Deneen declared the Actinoperative on the advice of his attorney general and refusedto appoint the five commissioners required by the Act.By 1907 the Special Park Commission had prepared itsown bill, but this failed to pass due to political infighting.Accordingly in 1909 both houses appointed a “Forest Preserve District and Outer Belt Commission of Illinois” toinvestigate the entire issue. Perkins and Jensen began theirquickly famous “Saturday Afternoon Walking Trips” inwhich they took this commission, other public leaders, andinterested individuals on tours of the proposed system.The Special Park Commission joined with the UnionAbove: Forest preserves weredesigned for wholesome outdoor family relaxation andrecreation.Left: From the beginning,supporters advocated conservation, and had fun doing it.The vintage photos in thisissue are by Dwight Perkinsand others. Now in thearchives of the Forest PreserveDistrict of Cook County, someof these “lantern slides” werehand-tinted long before colorphotography.WINTER 1999League Club, the City Club and the Chicago Associationof Commerce to form a new and more powerful lobbycalled the Forest Preserve District Association. This association greatly increased grass roots support and enlistedDaniel Burnham’s aid in his now-famous 1909 Plan forChicago, in which he noted that next in importance tolakefront preservation, “the woodlands should be broughtwithin easy reach of all people, especially the wage earners.” All these efforts worked, and a new bill satisfactory toIt was an odd spectacle. Perkins’ suitcharged that his own creation wasunconstitutional.everyone easily passed through the legislature and subsequent referendum. To Perkins, Jensen, and their friends,victory seemed near at hand.Again, however, politics intervened. Cook County BoardChairman William Busse appointed the five new commissioners—two Democrats and three Republicans—complying with the law that no more than three couldcome from one party. But Busse and his Republican administration had lost the recent elections and the Democratsregarded these new appointments as rightfully theirs. TheDemocrats sued to block Busse’s action and, although theCircuit Court of Cook County turned back their efforts, theattorney general (aided by lawyers from the DemocraticParty) found the forest preserve legislation unconstitutional. In 1911 the Illinois Supreme Court agreed, notingthat only those living in incorporated Chicago and Cicerohad been able to vote in the referendum.With that, the forest preserve movement nearly collapsed. The Forest Preserve District Association disbanded,and the Special Park Commission dropped the issue afterseeing more than a decade of precious time, and preciouslands, slip away. It remained for Perkins alone and a fewhardy followers to press the fight. This he did, and in 1914new legislation had again received approval from downstateand the voters. Perkins immediately challenged the billhimself to test its constitutionality, raising more than 2,000 to take the issue before the Circuit and SupremeCourts in 1915 and 1916.It was an odd spectacle. Perkins’ suit charged that hisown creation was unconstitutional, simply in order to getthat fight out of the way quickly. The court ruled “against”him, confirming the legality of the forest preserves statute.At that time the native landscape was the focus of anewly-emerging concept: the science of ecology. Its birthplace was the University of Chicago and its founder thebotany professor Henry Chandler Cowles. Cowles’ pioneering work over several decades established the concept thata native landscape is really a highly-diverse group of plantcommunities, the “residents” of each community adapted to7

one another and the community as a whole requiring speChicago landscape for what it is: a uniquely Midwesterncific physical factors—water, light, drainage, fire—topart of America, as precious as Chicago’s social fabric thatsurvive and thrive. Cowles’ work also revealed what hashad taken root in the same ground. Their goal was clear,been confirmed ever since: that the Chicago region is oneand presaged the homogenization of America by a century:of the most biologically rich areas in America.to preserve for future generations the original native landNot since the initial settlement of America some 250scape of Chicago, which even then was rapidlyyears before had a major urban Society been so close to andisappearing, because it gave strength to a local culture.original, untouched landscape. By Perkins’ time an appreci- These founders firmly believed that this landscape was cruation of regionalcial to the spiritual growth oflandscapes had flowered inthis great Midwestern town,America. This appreciationand was an integral part ofwas spawned by the emergwhat makes Chicago a specialing fields of city planningplace to live, work, and play.and landscape architectureWithin the first few years,(best exemplified by Olmmillions of visitors came tosted’s monumental creationthe new forest preserves,of Central Park in Newwhere the public was allowedYork in 1856); the growingto drive or roam at will. Peorecognition of the naturalple camped in the preserveswonders discovered in thefor months at a time, in someopening of the Americancases making these lands theirWest; and most ominouslypermanent summer homes.by the accelerating abilityA police force and regulaof industrial technology totions were established in 1917.alter and destroy the landSadly, ecology and landscape through mechanizedmanagement as understoodmeans.Perkins planned for the grandchildren—and their grandchildren. today were in their infancy atWhat Jensen, Perkins,the time. Fire in the landand other supporters saw around them was an originalscape was feared, and its role in ecology did not becomenative landscape still largely untouched since its creationclear until the 1940s through professor John Curtis’ pioby the last glaciers some 12,000 years before. This was aneering land restoration efforts at the University oflandscape of prairies, marshes, woodlands, and savannas,Wisconsin. Exotic plant species like buckthorn had yet toshaped by Midwestern climate and the regenerating firesarrive, and prolific native trees such as green ash and boxperiodically started by lightning or Native Americans.elder had yet to expand from their river bottom habitats.In 1916, the newly formed Forest Preserve District ofThus few people noticed the savannas and prairies slowlyCook County floated a 1,000,000 bond issue and in Sepfilling with brush. Few prairies had even been saved to starttember of that year purchased its first lands—Deer Grovewith. Late in his life, Jensen was asked why this was so. HisForest Preserve. By 1922 the District had purchased 21,500poignant answer was simple, and harked back decades toacres, and was well on its way to exceeding Perkins’ origiwhen native prairie, like the buffalo, was limitless: “Wenal goal of 37,000 acres.never thought it would all disappear.”The forest preserve founders clearly sought land for pubWorld War II and the ensuing development boomlic enjoyment through the many activities we find in thearound Chicago left our forest preserves largely forgotten inforest preserves today: hiking, cycling, field games, picnicsan era of “hands off” land management. For a time the preand other pursuits not-then dreamed of. But they sought toserves were even fair game for tollways and otherprovide these activities in an overall landscape preserved as “improvements” of the post-war era. Yet with the arrival ofit then existed, and had so for thousands of years. Jensen’sEarth Day and the environmental movement of the 1970s,vision was perhaps the clearest when he urged the saving of it was inevitable that a new generation would focus itsthese lands in their “primeval state.for the benefit of those attention on these landscapes.desiring knowledge of the plants indigenous there.”Chicago Wilderness is the natural next step in the conThis vision can be seen in the enabling legislation itselfservation of a noble heritage.which, with words unique in American landscape preservation law, requires the Forest Preserve District to “restore,Stephen F. Christy, Jr., a Chicago resident since 1976, has been therestock, protect and preserve” these lands “as nearly as mayExecutive Director of the Lake Forest Open Lands Associationbe, in their natural state and condition.”since 1985.Perkins, Jensen, and others were the first to see the8CHICAGO WILDERNESS

The Amateur and the Pro:Science at the Grass Rootsby Sheryl De VorePhotos by Kathy RichlandCitizen – a native member ofa nation, an inhabitant ofcity or town.Scientist – an expert in thestudy of the systematicknowledge of the world.rom the biologist with a doctoral degree to the 16-yearold girl who is learning toband her first bird, a growing number of us are playing large and smallroles in the development of conservation science.In an unchained sense of the word,all humans are “scientists,” gatheringfacts and performing experiments onthe Earth. And in the young, tenderworld of ecosystem restoration,opportunities abound for new ideas.Indeed, some of yesterday’s amateurscientists inspired some of the techniques used today to restore ournative ecosystems.Citizen scientists collect data thatprofessional and volunteer stewardscan use to help make good decisionsabout the managment of conservationlands. Citizen science also offers us achance to return to our human-nessas we immerse ourselves in prairies,woodlands and wetlands — countingBaltimore checkerspots, red-headedwoodpeckers, blue-spotted salamanders, and adder’s tongue ferns.What follows are profiles of sixChicago Wilderness citizen scientists,each exploring, contributing, andhaving a wild time.FWINTER 1999DENNIS DECOURCEY: TakingFlight—From Mentor to Mentorn one of his earliest photos, DennisDeCourcey is wearing diapers andfeeding a baby mule. He now directsthe Chicagoland Bird Observatory,where he still cares for young animals,but in another way.Dennis and the volunteers he trainsare banding birds and gathering datato help determine how to stop thedecline of certain populations of birds.“This is where I can make the mosteffective contribution to the naturalworld,” says Dennis. “I can also trainpeople who can make contributionslater on.”When Dennis was 11 years old, hemet his first bird banding teacher,Zella Schultz, who led a bird walk heattended. “She took me under herwing for the next five years,” says theBrookfield resident.In high school, Dennis worked onconservation issues with the localAudubon Society. He also played oboein the band. After graduation, hejoined the US Navy where he playedoboe for nearly five years.But the call of the wild was toostrong, and soon Dennis was workingas a zookeeper and later as curator ofbirds at the Brookfield Zoo. In 1990,IDennis, 51, and his wife, Leslie,founded the Chicagoland Bird Observatory.Bird banding is used worldwide tostudy the movement, survival, andbehavior of birds. Banders capture wildbirds, then place uniquely numberedmetal or plastic bands on their legs.Banders record where and when eachbird is banded, how old it is, its sex,and other information, which thengets sent to a central site. Whenbanded birds are later captured,released alive, and reported from somewhere else, scientists can reconstructan individual bird’s movement. Forinstance, banding has shown scientiststhat some species go south by onepathway and return north by another.Last spring, Dennis worked at GooseLake Prairie in Grundy County, IL,banding Henslow’s sparrows, a declining grassland species. This researchwill help scientists understand whathappens to Henslow's sparrow populations when grasslands are burned.The Observatory, based in Brookfield, IL, is one of some 300 stationsworldwide participating in a programcalled MAPS, Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship. “With thisprogram, as small as a 2 percentchange in population can be recognized,” says Dennis.His youngest volunteer, Nellie Carlson, began banding birds at theObservatory when she was 11 yearsold. “When you have a little tiny creature in your hand and can find out allthis information, it’s amazing,” saysNellie, now a 16-year-old high schoolsophomore who wants to study zoology. “Banding birds helps us knowabout nature and how it’s changing.”For more information or to getinvolved, call (708) 387-9265 ore-mail chibirdobs@earthlink.net F9

JUNE KEIBLER:Caretaker of Plants and Peoplenside a blooming eastern prairiefringed orchid June Keibler findswhat looks like a tiny, yellow, chickendrumstick. It is a pollinium, thepollen-bearing structure of this frillyflower, which she removes with atoothpick to transfer to another orchidin a process called hand-pollination.ICHRIS KUEHL:Family Values Mushroomn a recent family trip, Chris andKen Kuehl and their 13-year-olddaughter, Anna, discovered an inter-O10“These orchids need human help,”says June, a 54-year-old former physical therapist from Dundee, IL, whocares not only for humans but also forwild plants. Most of the populations ofthis federally threatened plant are toosmall to attract the hawk moths thatpollinate this species. “Through thefederal orchid recovery project, wehope to expand the existing populations as well as create new ones,” Junesays. “To do that, we need a consistentcensus of where the orchids are and aconsistent seed source. And we needvolunteers to do the many hours offield work required to make this program work.”Fifteen years ago, in between working and caring for her children, Junebegan volunteering to cut brush andcollect seeds at workdays in McHenryand Kane counties.She then learned about a draftrecovery plan for the orchid writtenby Marlin Bowles of the MortonArboretum for the US Fish & WildlifeService. The plan lists projects forscientists and volunteers so that theendangered plant can eventually be“delisted.”“The plan involves protecting sitesand expanding the existing populations by restoring habitat,” says Junewho coordinates volunteers on theproject. “Like many prairie plants, theorchid needs sunny, open areas. So weare clearing brush and burning.”June works with 60 loyal volunteers,many active for at least five years.Every summer they pollinate the smallpopulations of these plants, and everyfall they collect and disperse a portionof the seed to carefully selected possible new sites. They also censuspopulations and this year began theexacting task of collecting demographicinformation, including plant heightsand numbers of blooms per plant.“This project requires a teamapproach and every in

What is Chicago Wilderness? Chicago Wilderness is some of the finest and most significant nature in the temperate world, with roughly 200,000 acres of protected natural lands harboring native plant and animal communities that are more rare—and their survival more globally threatened— than the tropical ra