Transcription

ManagementMattersSAM DUMITRIUResearch Director, The Entrepreneurs Network

T HE EN T R EP R ENEU R S N E T WO R K2THE ENTREPRENEURS NETWORK ISA THINK TANK FOR THE AMBITIOUSOWNERS OF BRITAIN’S FASTESTGROWING BUSINESSES ANDASPIRATIONAL ENTREPRENEURS.A PROJECT BYBUSINESSSTAYUP.ORG#BUSINESSSTAYUP

M A N A GEMEN T M AT T ER S1CONTENTSFOREWORD 3INTRODUCTION: QUALITY AND QUANTITY 4Necessary and unnecessary business failure 5The Business Stay-Up Campaign 6MANAGEMENT MATTERS 8The long tail 8What makes a good manager? 11CASE STUDY: IMPROVING MANAGEMENT CAPABILITY IN INDIA 12Management really matters 14Why don’t good practices spread? 14Why are firms better managed in some countries? 15Access to advice 16CASE STUDY: 10,000 SMALL BUSINESSES 18The policy landscape 20THE STAY-UP AGENDA 21Recommendations 22Advisers 26About the Business Stay-Up Campaign IN PARTNERSHIP WITH27

T HE EN T R EP R ENEU R S N E T WO R K“The research method underpinningthe Business Stay-Up campaignfocuses on small firm growth andjob creation as hard indicators ofentrepreneurial success.”ROB MAYChief Executive Officer, Association of Business Executives2

M A N A GEMEN T M AT T ER S3FOREWORDPolicymakers worldwide are focusing on start-ups as an engine of longlasting economic growth and have set about creating the right conditionsto facilitate entrepreneurship. The start-up agenda has empoweredmany and continues to gather momentum. In 2016, the UK registeredthe equivalent of 70 new businesses per hour.ROB MAYChief Executive Officer,Association of Business ExecutivesABE is an education non-profit,operating globally to improvebusiness and entrepreneurialskills.However, this record rate of businessstart-up creation does not reflect thegoal of entrepreneurship policy, neitheris it a helpful indicator of wealthcreation. Downstream as many as 56%of these new businesses collapse within5 years. Therefore, we could questionthe level of impact that start-upshave on long-term productivity andemployment. The Business Stay-Upcampaign was established to explorewhat could be done to promoteentrepreneurial quality, as wellas quantity.Of course, in an efficient economy notevery business can or should flourish,some are simply outcompeted, andwe are not attempting to prevent allbusinesses from failing. But this reportshows that improving small firmengagement in business education,and management skills specifically,is a policy lever which can definitelysupport those businesses at the margin.Small business owners are usuallypassionate enthusiasts with great ideasand strong intentions to turn theirdream into a start-up success. But manyon that roller coaster entrepreneurialjourney find that they are attempting tolead and grow their enterprise withoutbasic business skills or knowledge, andmany assume that business acumen isa minor part of the entrepreneurshipequation. Such an approach is unlikelyto survive contact with reality.This report also highlights unresolvedchallenges around the perception andaccessibility of business education.For instance, an analysis of OECDdata finds that UK business ownersare lagging behind their contemporariesin 17 other countries when it comesto engaging in adult education andtraining.The research method underpinning theBusiness Stay-Up campaign focuseson small firm growth and job creationas hard indicators of entrepreneurialsuccess and reveals new evidence toclearly demonstrate the importanceof business education on raising theprobability of small firm survival.The report recommends some practicalpolicy developments to incentiviseeducational interventions in theentrepreneurial journey. Bold anddecisive ‘policy entrepreneurship’ is nowrequired to help small business ownersequip themselves with the managementskills needed to confront an arrayof huge and growing competitivechallenges, and to help more businessstart-ups to stay-up.

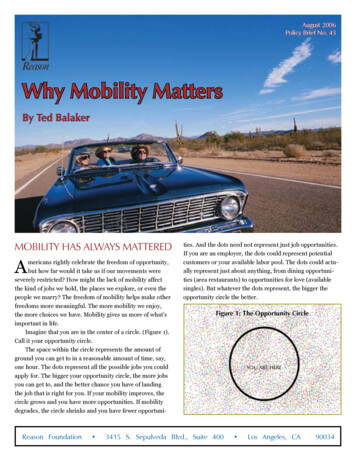

T HE EN T R EP R ENEU R S N E T WO R K4INTRODUCTION: QUALITY ANDQUANTITYThere is an argument to be made that the UK has the wrong attitude tofailure. Too often unsuccessful entrepreneurs are written-off by funders,journalists, and worst of all – themselves. That’s often a mistake– evidence suggests that entrepreneurs do better the second timearound.1 Samuel Beckett’s words “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Tryagain. Fail again. Fail better.” are rightly lauded by Silicon Valley.2 As asociety, we all benefit from the risk-takers who accept a high probabilityof failure to bring innovative products and services to market.But we shouldn’t fetishise failure.We may learn from our mistakes butas Peter Thiel (Founder of PayPal,Palantir, and Founders Fund) pointsout: “Most businesses fail for more thanone reason You will think it failedfor Reason 1, but it failed for Reasons1 through 5. And so the next businessyou start will fail for Reason 2, andthen for 3 and so on.” Failure can sapambition too, society can lose out iffuture ventures are less ambitious. Itgoes without saying that business failureis almost always a personal tragedy.Still, in a dynamic market economyfailure will be a fact of life. Overhalf of small business owners listcompetition as a major obstacle to thesuccess of their business.3 By its verynature competition has winners andlosers. When more efficient businessestake market share from inefficientincumbents by delivering betterproducts at lower prices, it shouldbe a cause for celebration.We should welcome Britain’s recordrate of new business creation (657,790new companies were founded in2016).4 It is right to toast more Britonsembracing an entrepreneurial mindset,but entrepreneurship isn’t an end initself. The focus ought to be on quality– innovation, growth, employment -not quantity. On that front, Britain isdoing well. The UK is home to 35% ofEurope’s tech unicorns (companies witha 1bn valuation) and has pulled inthree times more venture-capital thanany other European nation since 2016.5CHART 1: 5YR SURVIVAL RATE - UK, US, GERMANY, manyFranceSources: Small Business Administration, ONS Business Demography, Eurostat12345Lafontaine, F., & Shaw, K. (2016). “Serial entrepreneurship: Learning by doing?” Journal of Labor Economics, 34(S2), S217-S254.The same ethos is also expressed by “Fail fast, fail often” and Facebook’s old motto “Move Fast and Break Things”.Longitudinal Small Business Survey 2017: SME Employers (Businesses with 1-249 Employees, Department for Business, Energy, andIndustrial Strategy.Bounds, A. (2017) “Number of UK start-ups rises to new record.” The Financial TimesLondon and Partners (2018) “UK and London remain top European hubs for global tech investors”

M A N A GEMEN T M AT T ER S5“Failure ismassivelyoverrated.”PETER THIELEntrepreneur andVenture CapitalistBut not all firms succeed. In the UK, 56.8% of newbusinesses will close within their first five years.6 We are notoutliers either. Across the EU five-year survival rates hoveraround 50%, while the rate in the US is 48.2%.7We should look at survival and failure rates carefully. A highfailure rate may reflect a difficult business environment,but it could also signal a willingness to start and invest inriskier ventures. For instance, research from Prof Mark Hartat Aston University found that London has the lowest rateof start-up survival in the UK, but it also has the highestrate of high-growth entrepreneurship.8 Paradoxically, failurerates may be highest in the environments most conducive toquality entrepreneurship.Necessary and unnecessary business failureconvenient alternative to Blockbuster (ceased trading in2013), when Apple and Samsung displaced Kodak (filed forbankruptcy in 2012) by making high-quality digital camerasa standard feature for smartphones, and when Amazon’slow-prices and fast-delivery led to Maplins, Woolworths, andToys R Us shutting down. In most cases, any jobs lost wereeventually replaced with better-paying higher productivitywork.10Attempts to shield firms from competitive forces either bycreating barriers to entry or by tilting the tax system in favourof struggling incumbents should be avoided. This preventsgood practices from diffusing, locks-up capital in inefficientcompanies, and ultimately leads to ordinary consumerspaying more.Businesses can fail for many reasons. Paul Graham, founderof Y-Combinator, listed 18 different reasons for start-upsfailing.9 They range from bad hiring practices to failing tofocus on what consumers want. We ought to distinguishbetween necessary and unnecessary business failure. Nobusiness has an innate right to exist. Some ideas simply don’tpass the market test. Google-backed Juicero failed becausethere simply wasn’t a market for a 399 wi-fi enabled juicer.But not all business failures are necessary. Too often viablebusinesses fail due to poor managerial practices. FromTroubleshooter and Alex Polizzi: The Fixer to Ramsay’s KitchenNightmares and Mary Queen of Shops, there is a cottageindustry of reality TV shows where experienced businesspeople turnaround struggling small businesses. The advicegiven is often simple and formulaic, but provided thebusiness owner is willing to listen, it often works.Other times new ideas succeeding entails old ideas failing.Consumers won out when Netflix provided a moreThere’s no better example of the phenomena than CNBC’sThe Profit. In the show, Camping World CEO Marcus678910Business Demography, Office for National Statistics.Survival Rates and Firm Age, Small Business AdministrationBounds, A. (2017) “London start-ups are most likely to fail.” The Financial TimesGraham, Paul. (2006) “The 18 mistakes that kill startups.” Paul Graham.Mandel, M. (2017). How Ecommerce Creates Jobs and Reduces Income Inequality. Progressive Policy Institute, Washington, DC.

T HE EN T R EP R ENEU R S N E T WO R K6Lemonis buys stakes in promising, but failing, small- andmedium-sized enterprises and returns them to profitability.Unlike other shows, Lemonis only targets firms with soundunderlying business models. The companies he takes overtypically grew rapidly after an unexpected hit, but arenow struggling to control costs. Each episode follows apredictable formula, he runs the numbers to work out whichproducts are the best-sellers and which have the highestprice-to-cost margins. Lemonis then shifts production to thehighest-margin best-sellers, re-organises the shop floor andimplements a simple inventory management system to reducecosts. In many episodes, he also resolves personal issuesbetween sometimes-related staff members.11between education, skills and entrepreneurial success by GabrielHeller Sahlgren. The report revealed a strong link betweenbusiness owners’ area of specialist study and high-qualityentrepreneurship. Perhaps unsurprisingly, training obtainedthrough programmes in business, social science, and law,and in technical areas, such as engineering, are linkedto entrepreneurs employing more people, while otherareas of study are not. In particular, Heller Sahlgren findsthat programmes that offer task-related training do best.Entrepreneurs need to both learn best-practice managementtechniques and keep up-to-date with the latest developmentsin the industry in which they operate.Lemonis’ simple methods deliver impressive results. SweetPete’s, a sweet shop that Lemonis turned around grew from5 to 90 employees and increased its revenue by more thantenfold. While Mr Green Tea, an ice cream company heinvested in, has trebled its 2.5m valuation.“Fewer unnecessary failureswill create a more competitivebusiness environment,which will drive furtherimprovements in efficiencyand innovation benefittingsociety as a whole.”There is a growing body of evidence linking productivityto the uptake of the managerial best practices espoused byLemonis. Good managerial practice predicts a firm’s successbetter than R&D spending, IT spending or how skilled theirworkforce is.12 In fact, whether or not firms consistentlymonitor and improve their processes, set and revise targets,and incentivise employees through merit-based hiring, firing,and promotion procedures explains almost a third of thedifferences in productivity between and within countries.13Put simply, when businesses are well-managed they createmore jobs, pay higher wages, and sell better (and cheaper)products.Better advice and training can help businesses survive andwe should all want this. It makes sense – both morally andeconomically – to want as many business owners as possibleto have the skills to give it their best shot. Fewer unnecessaryfailures will create a more competitive business environment,which will drive further improvements in efficiency andinnovation benefitting society as a whole.Heller Sahlgren’s research highlights the need to investigatefurther both, which management training programmesdeliver the highest impact, and which policy levers are mosteffective at improving managerial quality across the economy.The CfEE’s report recommends that the government fundsrandomised trials to identify the most promising approachesto training and expands access and uptake through targetedtax breaks.In this report, we will set out the evidence on the linkbetween management skills and firm success, highlightschemes already up and running that promote high-qualityentrepreneurship, and build upon CfEE’s research to set outa policy agenda to equip Britain’s small and medium-sizedenterprises with the advice, training, and environment tosurvive and scale.The Business Stay-Up CampaignBusiness Stay-Up is a research-led campaign to promotehigh-quality entrepreneurship by drawing attention to theimportance of skills and management to helping Britishbusinesses survive and scale. As part of the campaign, theCentre for Education Economics (CfEE) has publishedHuman Capital and Business Stay-Up: the relationship111213Tabarrok, A. (2018). “Lessons from the Profit” Marginal RevolutionBloom, N., Van Reenen, J. and Brynjolfsson, E. (2017) “Good Management Predicts a Firm’s Success Better Than IT, R&D, or EvenEmployee Skills.” Harvard Business ReviewBloom, N., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2016). “Management as a technology?” Working Paper 16-133, Harvard Business School

M A N A GEMEN T M AT T ER S7

T HE EN T R EP R ENEU R S N E T WO R K8MANAGEMENT MATTERSThe first economist to spot the link between management andproductivity was Adam Smith. His famous study of a pin factoryhighlighted how through better organisation and specialisation theaverage worker could become 50 times more productive. But whileeconomists have long recognised the importance of managementand countless business books have analysed case studies of visionarymanagers and corporate leaders, only recently have economists beganempirically quantifying the impact of managerial quality on productivity,employment and output.Alexopolous and Tombe find that organisational innovationssuch Taylor’s Scientific Management, Motorola’s Six Sigma(popularised by GE’s Jack Welch), and Agile SoftwareDevelopment increased productivity and aggregate output byalmost as much as technological innovations.14 Yet often goodmanagement practices diffuse too slowly. There is a growingconcern that a divide between ‘superstar’ firms pushingforward at the technological and organisational frontier anda long tail of firms lagging behind is leading to increasinginequality and sluggish productivity.15141516The long tailChad Syverson finds that within a typical US industry themost productive tenth produce almost twice as much as theleast productive tenth with the same inputs.16 The situationis even more extreme in the UK. In a 2017 speech, the Bankof England’s Chief Economist Andy Haldane noted thatthe gap between our highest and lowest productivity firmswas larger than in the US, France or Germany. In particular,he drew attention to the fact that “In the services sector,the gap between the top- and bottom-performing 10% ofAlexopoulos, M, and Tombe, T. “Management matters.” Journal of Monetary Economics 59.3 (2012): 269-285.Autor, D., Dorn, D., Katz, L. F., Patterson, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2017). “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms.”IZA DP No. 10756Syverson, C. (2011). “What determines productivity?” Journal of Economic literature, 49(2), 326-65.

M A N A GEMEN T M AT T ER S9companies is 80% larger in the UK than in our internationalcompetitors”. Haldane argues that Britain’s productivityissues can be attributed to a failure of firms in the long tailto adopt the practices and processes of Britain’s highestachieving firms.17that management explains 29% of the difference betweenthe top and bottom performing 10% of companies in theUK. Improving the management skills of the UK’s marginalbusinesses would have a massive impact on productivity;Haldane estimates that closing the productivity gap betweenthe top and bottom three quartiles would boost UK GDPby 270bn. This is especially significant in the context of ahistoric pay squeeze driven by sluggish productivity growth.18The chart below shows that the UK has a significantlylarger tail of poorly managed firms when compared withGermany and the US. Bloom, Van Reenen and Sadun findCHART 2: UK, US AND GERMAN DISTRIBUTION OF MANAGEMENT ent scoreGreat Britain1718US45GermanySources: Bank ofEngland calculations.Haldane, A. (2018) The UK’s Productivity Problem: Hub No Spokes. Academy of Social Sciences Annual Lecture.Clarke, S. and Gregg, P. Count the pennies: Explaining a decade of lost pay growth, The Resolution Foundation.

T HE EN T R EP R ENEU R S N E T WO R K“There is strong evidencethat the adoption of multiplemeasurable techniques leadsto higher output.”10

M A N A GEMEN T M AT T ER SWhat makes a good manager?Taking a step back for a moment, it may sound strangethat we can measure and compare two firms and say oneis better-managed than another objectively. There are twocompeting perspectives on management. One sees goodmanagement as contingent and firm-specific. On this view,good management at Apple could be counter-productivemanagement at Sports Direct. There may also be crosscultural differences in management effectiveness, what worksfor a Japanese firm might not work for a British firm. Analternative view sees management as a form of technology.As managers adopt better techniques they become moreproductive regardless of the type of industry they operate in.19While there is likely some truth to the former view, there isstrong evidence that the adoption of multiple measurabletechniques leads to higher output and that within-industryproductivity differences are partially explained by withinindustry differences in management ability. Any attemptto measure management ability will be limited. The abilityof managers to analyse market conditions and make majorstrategic decisions will inevitably be hard to measure throughmultiple-choice questionnaires.For example, Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger founded amulti-featured check-in app called Burbn that competedwith FourSquare. Eventually Systrom and Krieger realisedthe app was overly complicated and that users were mainlyusing the app for its photosharing features. They decided topivot to photosharing and relaunched the app as Instagram,which they eventually sold for 1bn. It doesn’t seempossible to capture and systematically measure this kind of19Ibid11entrepreneurial savoir-faire in any survey response. Yet itappears to be the case that managers who perform well on themeasurable aspect of management also perform well on theharder to measure aspects of management.“An alternative view seesmanagement as a form oftechnology. As managers adoptbetter techniques they becomemore productive regardlessof the type of industry theyoperate in.”The World Management Survey (WMS) interviews plantmanagers, retail store managers, headteachers, clinical serviceleads and other middle managers. They’re asked open-endedquestions such as “Could you please tell me about how youmonitor your production process?” and scored out of 5 on18 different key management practices. The survey focuseson three key areas: monitoring, targets, and incentives/peoplemanagement. John Van Reenen, one of the economistsleading the project states, “a high scoring organizationfrequently monitors and tries to improve its processes,sets comprehensive and stretching targets, promotes highperforming employees and fixes (by re-training/rotating and,if unsuccessful, exit) underperforming employees.”

T HE EN T R EP R ENEU R S N E T WO R KCASE STUDYImproving ManagementCapability in IndiaWhile you don’t have to look far for examples of badmanagers on TV such as David Brent, Basil Fawlty,and Jack Donaghy, they’re typically bad in hard-tomeasure ways (for good reason, easily measurablebadness doesn’t make for entertaining TV). A better wayof understanding the idea that management is a formof technology on par with IT systems or mechanisedlooms is by looking at firms that lack the structuredmanagement practices we take for granted.12

M A N A GEMEN T M AT T ER S13One illustrative study looked at a management interventiontargeted at Indian textile firms.20 The firms in question are strikinglyinefficiently managed. The plant floors were disorganised, withchairs blocking access to poorly-maintained machinery and tools leftlying on the ground. Inventory rooms had months’ worth of excessyarn and lacked any formal labelling system with different types andcolours of yarn mixed up. It is easy to see how adopting modernformalised inventory systems could create significant improvementsin productivity for each factory.The textile plants were divided into three groups. Two of thegroups received a month long management diagnosis reportfrom Accenture, while the remaining plants did not. Of the two‘treatment’ groups, one received no more support after the initialdiagnosis, while the other received four months of implementationsupport.“It is easy to see how adoptingmodern formalised inventorysystems could create significantimprovements in productivity foreach factory.”The results were impressive. They cut quality defects by 50%,inventories by 40% and raised overall productivity by 10%. Whenthey followed the study up 10 years later, the researchers found thatfirms dropped about 40% of the adopted management practices,but there remained a 19.7 percentage point gap in managementpractices between the treatment and control plants. The researcherswere also able to impute a long-run 19% increase in labourproductivity since 2011.212021Bloom, N, et al. (2013) “Does management matter? Evidence fromIndia.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128.1 : 1-51.Bloom, N, Mahajan A., McKenzie D., and Roberts. J. (2018) “DoManagement Interventions Last? Evidence from India”, NBER WorkingPaper no. 24249.

T HE EN T R EP R ENEU R S N E T WO R KManagement really mattersHigh scores on the World Management Survey are linkedto stronger productivity, faster revenue and employmentgrowth, and a higher chance of firm survival. Bloom et alsurveyed managers at 32,000 US manufacturing plants,finding that management practices vary significantly betweenplants (40% of this variation is between plants in the samecompany).22 The study found that performance on the WorldManagement Survey explains 20% of productivity differencesbetween firms. To put that in context, management isas important as R&D and twice as important as IT forproductivity.A further study by Bender et al looked at medium-sizedGerman manufacturers.23 They found that managementscores were strongly correlated with firm-level productivity.Even after controlling for the fact that better managedfirms will tend to pay more to hire high-ability workers, therelationship between management and productivity remainedstrong. Another study by Bloom, Van Reenen and Sadunsurveyed 11,000 firms across 34 countries.24 The US had thehighest size-weighted management score and multinationalfirms had higher management scores than domestic firmsin each country surveyed. They found that differencesin management accounted for half the productivity gapbetween the US and the UK. Furthermore, they found thata 1 standard deviation increase in management score wasassociated with a 15% increase in total factor productivity.Focusing solely on SMEs, a recent study from the NationalInstitute of Economic and Social Research found thatSMEs were less likely to use formal management practicesthan larger firms, but the SMEs that did adopt formalmanagement practices were more productive and grewfaster.25 Furthermore, they found that returns were highestfor firms investing in human resource management practices,such as training and performance-related pay.As part of the Business Stay-Up campaign, Gabriel HellerSahlgren analysed over 10,500 business owners in 21countries using data from the OECD’s Programme for theInternational Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC)222324252627282914to study the impact of higher education on entrepreneurialsuccess.26 After controlling for a range of factors includingage, gender, first/second generation immigrant status,country-specific factors and numeracy/literacy scores, HellerSahlgren found that studying business, social science and lawpredicted firm success. Business owners with a background insocial science, business or law are 5% more likely to employ10 or more people compared with business owners withbackgrounds in general programmes.“High scores on the WorldManagement Survey are linkedto stronger productivity, fasterrevenue and employmentgrowth, and a higher chanceof firm survival.”Why don’t good practices spread?If formal management practices are so strongly linked toproductivity growth then it raises the question, why don’tmore firms adopt them? A recent Institute of Directors(IoD) study found that larger firms were more likely to haveadopted targeting, monitoring, and incentive strategies. Inparticular, only 56% of small firms invested in management/leadership training, while over 80% of large firms had.27Henderson and Gibbons identify four key reasons whySMEs fail to adopt management best practices: perception,inspiration, motivation, and implementation.28 First,managers may fail to spot that they’re behind if they’re failingto actively monitor worker productivity, as 60% of SMEIoD members say they are. An evaluation of the SwedishBusiness Development Program found that firms applyingfor business support benefited more from setting aside timeto assess business problems in order to fill out an applicationfor support than the support itself.29Bloom, N., Brynjolfsson, E., Foster, L., Jarmin, R. S., Patnaik, M., Saporta-Eksten, I., & Van Reenen, J. (2017). “What drivesdifferences in management?” (No. w23300). National Bureau of Economic Research.Bender, S., Bloom, N., Card, D., Van Reenen, J., & Wolter, S. (2018). Management practices, workforce selection, and productivity.Journal of Labor Economics, 36(S1), S371-S409.Bloom, N., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2016). “Management as a technology?” Working Paper 16-133, Harvard Business SchoolForth, J. and Alex B. (2018) “The impact of management practices on SME performance.” Discussion Paper No. 48, NIESRHeller Sahlgren, G. (2018) Human Capital and Business Stay-up, Centre for Education EconomicsParikh, T. (2018) Lifting the long tail: the productivity challenge through the eyes of small business lenders. Institute of DirectorsHenderson, R. and Gibbons, R. (2013) “What do managers do? Exploring Persistent Performance Differences among SeeminglySimilar Enterprises”in The Handbook of Organizational Economics, Princeton University Press, Princeton and OxfordParikh, T. (2018) Lifting the long tail: the productivity challenge through the eyes of small business lenders. Institute of Directors

M A N A GEMEN T M AT T ER SSecond, even when businesses knowthey’re falling behind they might notknow what to do about it. SMEs mayfind choosing between a course onAgile, Scrum or PRINCE2 puzzling.Without trusted advice on whichtechniques will best meet their business’needs they simply won’t risk investingin new training programmes that mightnot pay off.Third, managers may lack motivation.Even when they’ve diagnosed theproblem and identified a solution,managers may still lack an incentive totake the next step. The cost of trainingmay act as a barrier, as may the risk ofdisruption as working practices change.Finally, even when managers identifythe right practices and commit toinvesting in adopting them, they maystill struggle to implement them. Theirworkforce may be averse to changeand without changes to the company’sculture attempts to implement betterpractices may fail.303115Why are firms better managed insome countries?Bloom and Van Reenen analysedsurvey data from 732 medium-sizedmanufacturing firms across the UK, US,Germany, and France.30 They foundthat US firms were on average bettermanaged than European firms and thatmanagement scores were lowest in theUK. The UK (and to a lesser extentFrance) have low average managementscores in large part due to a long tailof badly managed terms. Bloom andVan Reenen identify two causes of theUK’s underperformance relative to theUS. First, they identify that UK andFrench firms have a higher proportionof family-firms that pass managementcontrol through primogeniture (firstborn son) rather than hiring outsidemanagers. They cite evidence showingthat while family ownership has a mixedeffect on profitability, family managementhas a significantly negative effect onprofitability. Second, Bloom and VanReenen find that poor managementpractices are more prevalent whenproduct market competition is weak.Together these two factors explain abouthalf of the long tail of poorly managedfirms and two-thirds of the Americanadvantage over European firms.In another paper Bloom et al identifythree other factors: business environment,learning spillovers, and human capital.31Comparing US states with “Rightto Work” laws which weaken unionpower an

on that roller coaster entrepreneurial journey find that they are attempting to lead and grow their enterprise without basic business skills or knowledge, and many assume that business acumen is a minor part of the entrepreneurship equation. Such an approach is unlikely to survive con