Transcription

M05 ROBB6743 08 SE C05.indd Page 105 9/24/15 4:52 PM user/206/PHC00193/9780133856743 ROBBINS/ROBBINS FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT8 SE 978013 .5CHAPTEROrganizationalStructure andDesignYou might not have heard of Empire Company Limited, butyou’ve probably shopped at one of their Sobeys, Safeway, orIGA grocery stores. Empire is a Canadian food-retailing andreal estate company based in Stellarton, Nova Scotia, with more than 17 billion in annual sales and more than 124 000 employees. Sobeyshas been serving Canadians for over 100 years, and one of the secretsto its competitive success is the synergy that comes from owning itsown retail real estate. With a lofty goal of being recognized as thebest food retailer and workplace environment in Canada, Empire hasmoved away from a regional management structure in order to reducecomplexity and eliminate duplication.The company streamlined its organizational structure to reflect itstransition to an operationally focused grocery retailer with relatedreal estate interests on the heels of an October 2013 announcementappointing Marc Poulin as CEO of both Empire Company Ltd. andSobeys Inc.1For Empire to be successful, the management structure requiressimplicity and clarity. What kind of organizational structure cansupport the operations of retail stores and real estate assets? The CEOhas a great deal of flexibility in determining some parts of thestructure and less flexibility in determining others. As a business withsignificant family ownership, Empire has been able to pursue a longterm growth strategy rather than focusing on short-term financialresults. Empire continues to expand, adding gas stations from ShellCanada in 2014.In this chapter, we present information about designing appropriate organizationalstructures. We look at the various elements of organizational structure and the factors that influence their design. We also look at some traditional and contemporaryorganizational designs, as well as organizational design challenges that today’smanagers face.Felix Choo/AlamyPART 3 OrganizingLEARNING OUTCOMES5.1 Tell What are the majorelements of organizationalstructure?1065.2 Define What factors affectorganizational structure?1135.3 Describe Beyond traditionalorganizational designs, howelse can organizations bestructured?116Think About ItHow do you run retail stores andinvest in real estate ventures? Putyourself in CEO Marc Poulin’sshoes. How can you continue tomake Empire successful? Whatorganizational structure will bestensure Empire’s goals?

M05 ROBB6743 08 SE C05.indd Page 106 9/24/15 4:52 PM user/206/PHC00193/9780133856743 ROBBINS/ROBBINS FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT8 SE 978013 .106 PAR T 3 O r ga n i zi ng5.1Tell What are the majorelements of organizationalstructure?Defining Organizational StructureNo other topic in management has undergone as much change in the past few yearsas that of organizing and organizational structure. Managers are questioning andre-evaluating traditional approaches to organizing work in their search for organizationalstructures that can achieve efficiency but also have the flexibility necessary for successin today’s dynamic environment. Recall from Chapter 1 that organizing is defined as theprocess of creating an organization’s structure. That process is important and servesmany purposes (see Exhibit 5-1). The challenge for managers is to design anorganizational structure that allows employees to work effectively and efficiently.Just what is organizational structure? It is how job tasks are formally divided, grouped,and coordinated within an organization. When managers develop or change the structure,they are engaged in organizational design, a process that involves decisions about six keyelements: work specialization, departmentalization, chain of command, span of control,centralization and decentralization, and formalization.2miskolin/FotoliaWork SpecializationAdam Smith first identified division of labour and concluded that it contributed toincreased employee productivity. Early in the twentieth century, Henry Ford appliedthis concept in an assembly line, where every Ford employee was assigned a specific,repetitive task.Today we use the term work specialization to describe the degree to which tasks in anorganization are subdivided into separate jobs. The essence of work specialization is thatan entire job is not done by one individual but instead is broken down into steps, and eachstep is completed by a different person. Individual employees specialize in doing part of anactivity rather than the entire activity. When work specialization was implemented in theearly twentieth century, employee productivity rose initially, but when used to extreme,human diseconomies from work specialization—boredom, fatigue, stress, poor quality,increased absenteeism, and higher turnover—more than offset the economic advantages.Most managers today see work specialization as an important organizing mechanism butnot as a source of ever-increasing productivity. McDonald’s uses high work specializationto efficiently make and sell its products, and employees have precisely defined roles andstandardized work processes. However, other organizations, such as Bolton, Ontario–based Husky Injection Molding Systems and Ford Australia, have successfully increasedjob breadth and reduced work specialization. Still, specialization has its place in someorganizations. No hockey team has anyone play both goalie and centre positions. Rather,players tend to specialize in their positions.EXHIBIT 5-1Purposes of Organizing Divides work to be done into specific jobs and departments Assigns tasks and responsibilities associated with individual jobs Coordinates diverse organizational tasks Clusters jobs into units Establishes relationships among individuals, groups, and departments Establishes formal lines of authority Allocates and deploys organizational resourcesorganizingorganizational structurework specializationA management function that involves determiningwhat tasks are to be done, who is to do them, howthe tasks are to be grouped, who reports to whom,and where decisions are to be made.How job tasks are formally divided, grouped, andcoordinated within an organization.The degree to which tasks in an organization aresubdivided into separate jobs; also known asdivision of labour.organizational designThe process of developing or changing anorganization’s structure.

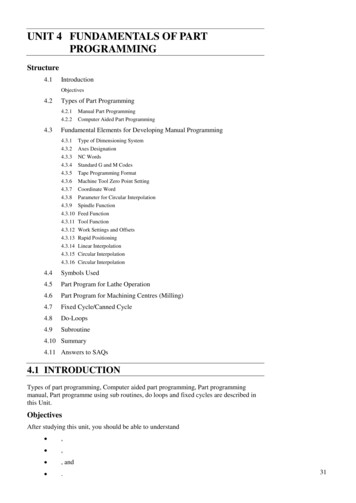

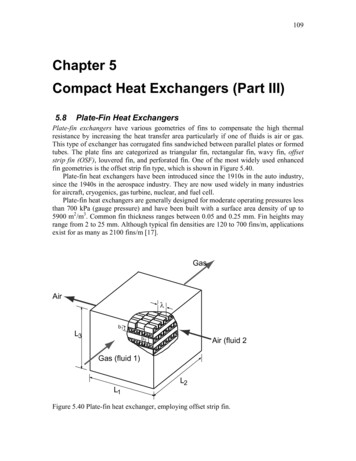

M05 ROBB6743 08 SE C05.indd Page 107 9/24/15 4:52 PM user/206/PHC00193/9780133856743 ROBBINS/ROBBINS FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT8 SE 978013 .CHAP T ER 5 O r ga niza tio na l S tr u ct ure an d De sig ical departmentalizationcustomer departmentalizationThe basis on which jobs are grouped together.Grouping jobs on the basis of territory orgeography.Grouping jobs on the basis of customers who havecommon needs or problems.Grouping jobs by functions performed.process departmentalizationcross-functional teamsproduct departmentalizationGrouping jobs on the basis of product or customerflow.Work teams made up of individuals who are expertsin various functional specialties.functional departmentalizationGrouping jobs by product line.Dick HemingwaySergey Nivens/Fotoliaqstockmedia/FotoliaDoes your college or university have an office of student affairs? A financial aid or studenthousing department? Once jobs have been divided up through work specialization, theyhave to be grouped back together so that common tasks can be coordinated. The basis onwhich jobs are grouped together is called departmentalization. Every organization willhave its own specific way of classifying and grouping work activities. Exhibit 5-2 showsthe five common forms of departmentalization.Functional departmentalization groups jobs by functions performed. This approachcan be used in all types of organizations, although the functions change to reflect the organization’s purpose and work. Product departmentalization groups jobs by product line. Inthis approach, each major product area is placed under the authority of a manager who isresponsible for everything having to do with that product line. For example, Estée Laudersells lipstick, eyeshadow, blush, and a variety of other cosmetics represented by differentproduct lines. The company’s lines include Clinique and Origins, in addition to Canadiancreated MAC Cosmetics and its own original line of Estée Lauder products, each of whichoperates as a distinct company.Geographical departmentalization groups jobs on the basis of territory or geography,such as the East Coast, Western Canada, or Central Ontario, or maybe by US, European,Latin American, and Asia–Pacific regions. Process departmentalization groups jobs onthe basis of product or customer flow. In this approach, work activities follow a naturalprocessing flow of products or even of customers. For example, many beauty salons haveseparate employees for shampooing, colouring, and cutting hair, all different processesfor having one’s hair styled. Finally, customer departmentalization groups jobs on thebasis of customers who have common needs or problems that can best be met by havingspecialists for each. There are advantages to matching departmentalization tocustomer needs.Large organizations often combine forms of departmentalization. Forexample, a major Canadian photonics firm organizes each of its divisions alongfunctional lines: its manufacturing units around processes, its sales units aroundseven geographic regions, and its sales regions into four customer groupings.Two popular trends in departmentalization are the use of customerdepartmentalization and the use of cross-functional teams. Toronto-based DellCanada is organized around four customer-oriented business units: home andhome office; small business; medium and large business; and government,education, and health care. Customer-oriented structures enable companies tobetter understand their customers and to respond faster to their needs.Managers use cross-functional teams—teams made up of groups of individuals who are experts in various specialties and who work together—toincrease knowledge and understanding for some organizational tasks. Scarborough, Ontario–based Aviva Canada, a leading property and casualty insuranceBurnaby, British Columbia–based TELUS is structuredgroup, puts together cross-functional catastrophe teams, with trained represen- around four customer-oriented business units to improvetatives from all relevant departments, to more quickly help policyholders when customer response times: consumer solutions (focuseda crisis occurs. During the BC wildfires of summer 2003, the catastrophe team on services to homes and individuals); business solutionsworked on both local and corporate issues, including managing information (focused on services to small and medium-sizedtechnology, internal and external communication, tracking, resourcing, and businesses and entrepreneurs); TELUS Québec (a TELUScompany focused on services for the Quebecvendors. This type of organization made it easier to meet the needs of policy- marketplace); and partner solutions (focused on servicesholders as quickly as possible.3 We discuss the use of cross-functional teams to wholesale customers, such as telecommunicationsmore fully in Chapter 10.carriers and wireless communications companies).

/206/PHC00193/9780133856743 ROBBINS/ROBBINS FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT8 SE 978013 .M05 ROBB6743 08 SE C05.indd Page 108 9/24/15 4:52 PM user108 PAR T 3 O r ga n i zi ngEXHIBIT 5-2The Five Common Forms of DepartmentalizationFunctional DepartmentalizationPlant ManagerManager,EngineeringManager,Accounting ––Manager,ManufacturingManager,Human ResourcesManager,PurchasingEfficiencies from putting together similar specialties andpeople with common skills, knowledge, and orientationsCoordination within functional areaIn-depth specializationPoor communication across functional areasLimited view of organizational goalsGeographical DepartmentalizationVice-Presidentfor SalesSales Director,Western Region ––Sales Director,Prairies RegionSales Director,Central RegionSales Director,Eastern RegionMore effective and efficient handling of specific regionalissues that ariseBetter service of needs of unique geographic marketsDuplication of functionsFeelings of isolation from other organizational areas possibleProduct DepartmentalizationSource: Bombardier Annual portationCommercial AircraftRail VehiclesRegional AircraftTotal Transit SystemsBusiness AircraftPropulsion and ControlsAmphibious AircraftServicesMilitary Aviation TrainingRetail Control SolutionsFlexjetBogiesSkyjet ––Specialization in particular products and services possibleManagers able to become experts in their industryCloser to customersDuplication of functionsLimited view of organizational goalsProcess mentManagerPlaningand MillingDepartmentManager –Lacqueringand rFinishingDepartmentManagerMore efficient flow of work activitiesUse possible only with certain types of productsCustomer DepartmentalizationDirectorof SalesManager,Retail Accounts ––Manager,Wholesale AccountsManager,Government AccountsSpecialists able to meet customers’ needs and problemsDuplication of functionsLimited view of organizational goalsInspectionand ShippingDepartmentManager

/206/PHC00193/9780133856743 ROBBINS/ROBBINS FUNDAMENTALS OF MANAGEMENT8 SE 978013 .M05 ROBB6743 08 SE C05.indd Page 109 9/24/15 4:52 PM userCHAP T ER 5 O r ga niza tio na l S tr u ct ure an d De sig n109Chain of CommandThe chain of command is the continuous line of authority that extends from upperorganizational levels to the lowest levels and clarifies who reports to whom. It helpsemployees answer questions such as “Who do I go to if I have a problem?” or “To whomam I responsible?”You cannot discuss the chain of command without discussing these

When managers develop or change the structure, they are engaged in organizational design, a process that involves decisions about six key elements: work specialization, departmentalization, chain of command, span of control, centralization and decentralization, and formalization.2. Work Specialization.