Transcription

Introduction to Ergonomics

Essential ReadingErgonomics for Beginners, 2nd editionJan Dul, Erasmus University, The Netherlands and B. A. Weerdmeester, TNOInstitute, The NetherlandsTaylor & FrancisPbk 0-7484-0825-8A Guide to Methodology in Ergonomics: Designing for Human UseNeville Stanton and Mark Young, Brunel University, UKTaylor & FrancisPbk 0-7484-0703-0Fitting the Task to the Human, 5th editionK. Kroemer and E. GrandjeanTaylor & FrancisHbk 0-7484-0664-6; Pbk 0-7484-0665-4Evaluation of Human Work, 2nd editionJohn Wilson and Nigel Corlett, The University of Nottingham, UKTaylor & FrancisHbk 0-7484-0083-4; Pbk 0-7484-0084-2For price availability and ordering visit our website www.ergonomicsarena.comAlternatively our books are available from all good bookshops.

Introduction to ErgonomicsR.S. Bridger

First edition published 1995 by McGraw-Hill, Inc.This edition published 2003 by Taylor & Francis11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EESimultaneously published in the USA and Canadaby Taylor & Francis Inc,29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001Taylor & Francis is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis GroupThis edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. 2003 Robert BridgerAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproducedor utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means,now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording,or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission inwriting from the publishers.Every effort has been made to ensure that the advice and information inthis book is true and accurate at the time of going to press. However,neither the publisher nor the authors can accept any legal responsibility orliability for any errors or omissions that may be made. In the case of drugadministration, any medical procedure or the use of technical equipmentmentioned within this book, you are strongly advised to consult themanufacturer’s guidelines.British Library Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryLibrary of Congress Cataloging in Publication DataA catalogue record has been requestedISBN 0-203-42613-4 Master e-book ISBNISBN 0-203-44054-4 (Adobe eReader Format)ISBN 0-415-27378-1 (pbk)0-415-27377-3 (hbk)

Para Barbara, Daniella y Angelo

Allie

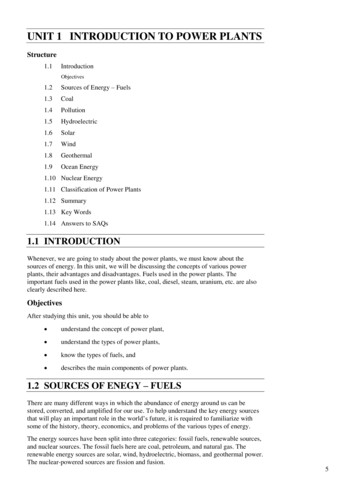

ContentsPreface to the second edition1 Introductionxii1The focus of ergonomics 2Ergonomics and its areas of application in the work system 10A brief history of ergonomics 11Attempts to ‘humanise’ work 19Modern ergonomics 21Effectiveness and cost effectiveness 26Future directions for ergonomics 31Summary 31Essays and exercises 322 Anatomy, posture and body mechanics33Some basic body mechanics 34Anatomy of the spine and pelvis related to posture 36Postural stability and postural adaptation 42Low back pain 44Risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders in the workplace 48Behavioural aspects of posture 53Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 55Research directions 56Summary 56Essays and exercises 573 Anthropometric principles in workspace and equipment designDesigning for a population of users 58Sources of human variability 58Anthropometry and its uses in ergonomics 60Principles of applied anthropometry in ergonomics 69Application of anthropometry in design 76Design for everyone 7958

viii ContentsAnthropometry and personal space 83Effectiveness and cost-effectivness 84Research directions 86Summary 86Essays and exercises 874 Static work: Design for standing and seated workers89Fundamental aspects of standing and sitting 90An ergonomic approach to workstation design 96Design for standing workers 103Design for seated workers 107Worksurface design 110Visual display units 112Guidelines for the design of static work 113Effectiveness and cost-effectivness 116Research directions 118Summary 119Essays and exercises 1205 Design of repetitive tasks121Introduction to work-related musculoskeltal disorders 121Injuries to the upper body at work 128Review of tissue pathomechanics and WMSDs 129Disorders of the neck 134Carpal tunnel syndrome 137Tennis elbow (epicondylitis) 139Disorders of the shoulder 140Lower limbs 142Ergonomic interventions 143Trends in work-related musculoskeltal disorders 151Effectiveness and cost-effectivness 153Research directions 156Summary 156Essays and exercises 1576 Design of manual handling tasksAnatomy and biomechanics of manual handling 158Prevention of manual handling injuries in the workplace 161Design of manual handling tasks 171Carrying 178Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 184Research issues 186158

Contents ixSummary 186Essays and exercises 1867 Work capacity, stress and fatigue187Stress and fatigue 187Muscles, structure, function and capacity 188The cardiovascular system 199The respiratory system 200Physical work capacity 200Factors affecting work capacity 205Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 210Research issues 212Summary 212Essays and exercises 2138 Industrial applications of physiology214Measurement of the physiological cost of work 215Applied physiology in the workplace 218Fitness for work 223Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 228Research issues 230Summary 230Essays and exercises 2319 Heat, cold and the design of the physical environment233Fundamentals of human thermoregulation 233Measuring the thermal environment 235Thermoregulatory mechanisms 237Work in hot climates 239Work in cold climates 242Skin temperature 246Protection against extreme climates 247Comfort and the indoor climate 250ISO standards 256Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 256Research directions 260Summary 260Essays and exercises 26110 Vision, light and lightingVision and the eye 262Measurement of light 274262

x ContentsLighting design considerations 278Visual fatigue, eyestrain and near work 286Psychological aspects of indoor lighting 288Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 289Research issues 293Summary 293Essays and exercises 29311 Hearing, sound, noise and vibration295Terminology 296The ear 296Measurement of sound 303Ear protection 309Design of the acoustic environment 311Industrial noise control 314Noise and communication 317The auditory environment outdoors 317Effects of noise on task performance 318Non-auditory effects of noise on health 319Noise and satisfaction 320Vibration 321Effectiveness and cost effectiveness 323Research issues 327Summary 327Essays and exercises 32812 Human information processing, skill and performance329A general information processing model of the user 329Cognitive systems 351Problem solving 352Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 357Research issues 358Summary 358Essays and exercises 35813 Displays, controls and virtual environmentsPrinciples for the design of visual displays 360Auditory displays 375Design of controls 379Combining displays and controls 386Virtual (‘synthetic’) environments 392Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 396Research issues 399360

Contents xiSummary 399Essays and exercises 40014 Human–computer interaction, memory and language401Human-centred design processes for interactive systems 402Designing information in external memory stores 407Human-computer dialogues 413Memory and language in everyday life 418Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 427Research issues 433Summary 434Essays and exercises 43415 Human–machine interaction, human error and safety436Human error and equipment design 436Mental workload in human machine interaction 442Psychological aspects of human error 445Characterising human–machine interaction 454GOMS 459Prevention of error in human–machine interaction 460Accidents and safety 467Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 471Research issues 475Summary 476Essays and exercises 47616 System design: organisational and social aspects477Systems design methods for ergonomics 477Organisational aspects: some macroergonomic examples 481Psychosocial factors 495Litigation 503Cross-cultural considerations 504Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness 505Research directions 507Summary 507Essays and exercises 508Further readingReferencesIndex509511543

Preface to the second editionCan it work, does it work, is it worth it?1 These three questions have been foremostin my mind throughout the revision of ‘Introduction to Ergonomics’. In revising andupdating the text, I have tried to attain three goals. First, to update the scientificcontent of the book to reflect the state of our knowledge at the beginning of thetwenty-first century. Second, to maintain the book’s essential character as a generalintroductory text that teaches the basic science that ergonomists use at work. Third,to add new material at the end of every chapter to answer the three questions above.There is a great deal of evidence that ergonomics does work. It really does improvethe interactions between people and machines and it really can make systems workbetter. How to demonstrate this has been one of the challenges in the process ofrevision. Several criteria have influenced the selection of supporting evidence. It wouldbe ideal if evidence for the benefits of all of the diverse practices and subdisciplinesof ergonomics came in the form of randomised controlled trials with double-blindapplication of treatments to satisfy even the most sceptical reviewer. This is not thecase, and it never can be, so I have tried to present a variety of evidence that bestexemplifies what each particular area has to offer.The evidence comes in the form of field trials, field experiments, longitudinalstudies and even a few laboratory experiments. Such a variety of research methodswill never please everyone – what satisfies the university academic may seem dry andother-worldly to the production manager. Uncontrolled trials in real factories maynot impress the academic, but practitioners may find therein much useful ammunition for arguing their cause.Another theme that is pursued throughout the book is that engineering and designare increasingly driven by standards. Probably the best evidence that the valueof ergonomics is now recognised is the publication of international standards forergonomics. These standards are paving the way for a new, quantitative and muchmore precise form of practice. With this in mind, I have tried to inform the readerabout these standards, wherever possible (with the rider that this is a textbook, nota design manual). The reader is encouraged to use these standards in practice and,with due deference to national bodies, the International Organization for Standardization (IOS) is recommended as the first port of call.In keeping with these modern trends, some new essays and exercises have beenadded to encourage the learning of quantitative skills. Some of the older, perhaps1Haynes. 1999. Can it work? Does it work? Is it worth it? British Medical Journal, 319 (Sep. 11): 652–653.

Preface to the second edition xiiimore frivolous, illustrations have been replaced by new drawings illustrating modernresearch in ergonomics. These have been rendered, in her customary ‘estilo cuadradito’,by Rina Araya, my graphic artist in Chile. Restrictions on the length of the book haveled to some fairly ruthless editing to make way for new material. It is hoped thatlecturers will continue to find much useful material to structure their courses and toillustrate the concepts of ergonomics and, at the end of their courses, that studentswill be able to give the following correct answers to the three opening questions:‘Yes, it can, Yes, it does, Yes it is!’R. S. BridgerLee-on-the-SolentHants, UK2002

Allie

Introduction 11IntroductionIn the past, the man has been first; in the future, the system must be first.(Frederick Winslow Taylor, The Principles of Scientific Management, 1911, p. 7)Ergonomics is the study of the interaction between people and machines and thefactors that affect the interaction. Its purpose is to improve the performance ofsystems by improving human machine interaction. This can be done by ‘designing-in’a better interface or by ‘designing-out’ factors in the work environment, in the taskor in the organisation of work that degrade human–machine performance.Systems can be improved by Designing the user-interface to make it more compatible with the task and theuser. This makes it easier to use and more resistant to errors that people areknown to make.Changing the work environment to make it safer and more appropriate for thetask.Changing the task to make it more compatible with user characteristics.Changing the way work is organised to accommodate people’s psychological,and social needs.In an information processing task, we might redesign the interface so as to reduce theload on the user’s memory (e.g. shift more of the memory load of the task onto thecomputer system or redesign the information to make it more distinctive and easierto recall). In a manual handling task, we might redesign the interface by addinghandles or using lighter or smaller containers to reduce the load on the musculoskeletalsystem. Work environments can be improved by eliminating vibration and noise andproviding better seating, desking, ventilation or lighting, for example. New taskscan be made easier to learn and to perform by designing them so that they resembletasks or procedures that people are already familiar with. Work organisation canbe improved by enabling workers to work at their own pace, so as to reduce thepsychophysical stresses of being ‘tied to the machine’ or by introducing subsidiarytasks to increase the range of physical activity at work and provide contact withothers.The implementation of ergonomics in system design should make the system workbetter by eliminating aspects of system functioning that are undesireable, uncontrolledor unaccounted for, such as

2 Introduction to ergonomics Inefficiency – when worker effort produces sub-optimal output.Fatigue – in badly designed jobs people tire unnecessarily.Accidents, injuries and errors – due to badly designed interfaces and/or excessstress either mental or p

Evaluation of Human Work, 2nd edition John Wilson and Nigel Corlett, The University of Nottingham, UK Taylor & Francis Hbk 0-7484-0083-4; Pbk 0-7484-0084-2 For price availability and ordering visit our website www.ergonomicsarena.com Alternatively our books are available from all good bookshops. Introduction to Ergonomics R.S. Bridger. First edition published 1995 by McGraw-Hill, Inc. This .