Transcription

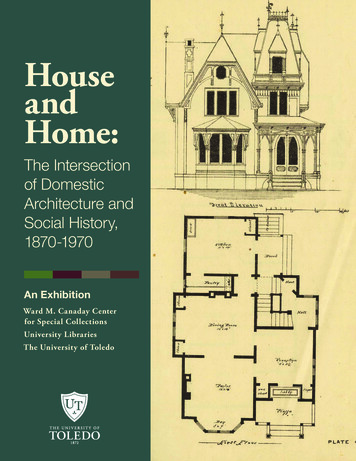

HouseandHome:The Intersectionof DomesticArchitecture andSocial History,1870-1970An ExhibitionWard M. Canaday Centerfor Special CollectionsUniversity LibrariesThe University of Toledo

House and Home:The Intersection of Domestic Architectureand Social History, 1870-1970An ExhibitionWard M. Canaday Center for Special CollectionsUniversity LibrariesThe University of ToledoOctober 19, 2016 – May 5, 2017Catalog Contributors:Barbara FloydTamara JonesRichard KruzelSara MouchArjun SabharwalLauren WhiteEdited by Barbara FloydAn Exhibition Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections1

TABLE OF CONTENTSIntroduction3Chapter 1.5Chapter 2.14Chapter 3.23Selected Bibliography35Home and Hearth: Houses of theVictorian Era, 1870-1900Home, Head, and Hand: The Artsand Crafts of Housing, 1900-1940Home and Happiness: ModernArchitecture and Modern Living,1940-19702House and Home: The Intersection of Domestic Architecture and Social History, 1870-1970

House and Home:The Intersection of Domestic Architectureand Social History, 1870-1970INTRODUCTIONHome. There are few words in the Englishlanguage that evoke so much sentiment.Home is the place of family, of warmth, ofsecurity. It is where we came from, andwhere we retreat to. It is our personalsanctuary, where the intimate details of ourlives are lived outside of public scrutiny. Itis also where we invite our friends in to beentertained. It is the most expensive singlepurchase of our lives, and as such, it is asymbol of our success. We decorate it inways that we hope show off our characterand express who we are.There is something unique about the way the Americanmiddle class has come to think about where they live, aresult of decades of promotion of the concept of homeby architects, builders, designers, salesmen, and socialcommentators. While today we may be glued to ourtelevisions watching HGTV, in the 19th century we pagedthrough pattern books of architectural plans for our dreamhouse and read domestic manuals detailing the best waysto manage it. In later years, we pored over images of housessold in catalogs as kits, magazines showing trends in interiordesign, and advertisements enticing us with the latest inhome innovation.Most of these outlets that promoted the perfect home andtherefore the perfect family and perfect life were—andstill are—aimed at women. The social role of women hasin many ways defined the style of American middle-classhomes, both inside and out. The Victorian Gothic or QueenAnne house of the late 19th century was a three-dimensionalexpression of the Cult of Domesticity, where virtuouswomen raised virtuous children in a house that looked morelike a church than a residence. The home had public partslike the parlor where wives could show off their taste, style,and wealth to guests who came calling, and private partswhere they managed the servants, cared for the children,insured that their hard-working husbands were emotionallysupported, and created “fancywork” embellishmentsfor every surface. In return for these sacrifices, societyworshipped the women who resided in these sanctuaries.In the first three decades of the 20th century, critics of thissocial order and women’s own desires to have a fuller lifethat included activities in the public realm (like voting)brought about a new type of house. Called a “bungalow,”it was much smaller and simpler, with clean, unclutteredlines. Where once there was a parlor for greeting guests,there was now a “living room” where private family life andpublic entertaining both occurred. Smaller houses werealso a necessity since few families could afford servantsanymore. The “housewife” was born—the woman weddedto her house who personally cooked and cleaned and washedrather than directing someone else to do these activities.Smaller houses were also more affordable, expandinghomeownership to a much larger group of Americans.After two decades of economic depression and war, the“modern” concept of home reflected yet another change inthe roles of American middle-class women. By 1950, womenput aside the work they performed out of necessity in warproduction factories, and returned to their more traditionalrole as wife and mother. The post-war house was built inhuge suburban tracts accessible via the interstate highwaysystem. These houses often included new innovations thatwere advertised as ways to make housekeeping easier, likedishwashers and electric stoves and washing machines. TheAn Exhibition Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections3

bungalow design was replaced by the ranch house, whichwas long and low and evocative of the carefree lifestyleof California. Large picture windows literally framed thehappy family that lived inside. The post-war American homeheld such sway over our collective imaginations that it waseven the subject of one of the most heated internationalpolitical debates of the Cold War era, between the premierof the Soviet Union and the vice president of the UnitedStates, over which country had the most advanced kitchentechnology.But while women were led to believe that suburbanliving— with all of its technological innovations—wouldprovide everything they could ever want, by the 1960s,many found this lifestyle wanting. Women felt isolated inthe suburbs. With new educational opportunities and theability to limit the number of children they gave birth to,they sought a life outside the home, just like their husbandshad, that sometimes included a career. At the same time, theadvertisers and marketers who promoted the importance ofthe middle-class life stressed that women could work outsidethe home, but still provide a warm, nurturing environmentfor her family inside the home. Women could have it all.This exhibit, House and Home: The Intersection of DomesticArchitecture and Social History, 1870 to 1970, looks at howthe American home changed to reflect the changing roleof women and the evolution of the family. For over 40years, the Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collectionshas been actively collecting books that help to documentthe social history of American middle-class women. Thisincludes an amazingly rich collection of architecturalpattern books, domestic manuals, women’s periodicals,home catalogs, and guides to interior home design, many ofwhich are displayed in this exhibit.As with any project this size, this exhibit represents thework of many. Most importantly is the staff of the CanadayCenter, who researched and wrote the catalog and exhibitlabels and mounted the exhibition: Sara Mouch, LaurenWhite, Tamara Jones, Arjun Sabarwal, and Richard Kruzel.Suzanne Henry provided valuable design assistance, and thecatalog was designed by Amanda Ngur in UT’s Marketingand Communication Department. Our speakers’ seriesbrought in lecturers who spoke on the eras of housingcovered by this exhibition. The Wood County HistoricalSociety lent us items for the exhibition. My thanks tocurator Holly Hartlerode for her assistance in arranging theloan of these items.A related exhibit, Comfort and Convenience: ToledoCorporations and Post-War Housing Innovation, looks atthe many ways Toledo corporations fueled the post-warhousing boom of the 1950s and 1960s by inventing newproducts that made homes more livable. In particular,Libbey-Owens-Ford and Owens-Corning Fiberglasproduced products that are ubiquitous in housing built inthe 1950s to the 1970s. Some of these products includedglass blocks, picture windows, insulation, Fiberglasdraperies, sliding doors, mirror walls, Fiberglas screens,Vitrolite walls, and even proposals for space-age kitchens.The marketing of these products in the popular magazinesof the day made them essential to anyone—especiallywomen—who hoped to have the newest and best homes tocreate happy and contented families. The exhibit featuresadvertisements for these products.Barbara FloydDirector, Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections andInterim Director, University LibrariesOctober 20164House and Home: The Intersection of Domestic Architecture and Social History, 1870-1970

Chapter 1.Home and Hearth:Houses of the Victorian Era, 1870-1900The Civil War was a watershed betweenan agrarian America and an industrialAmerica. In the North, demands forproducts required to wage war hadcreated an industrial boom. Lack ofaccess to Southern ports fueled newtransportation lines that remainedimportant after the war and created neweconomic opportunities. While the war’sdevastation in the South would continue toimpact that region’s growth for decades tocome, the North’s strong economy drewimmigrants who flooded into Northerncities looking for jobs not available in theirnative countries. The booming economyand immigration drove a demand forhousing.IMMIGRANTS IMPACT THE URBANLANDSCAPEIn the decades after the Civil War, the urban landscape ofthe United States pointed to a complex relationship betweenthose who were the descendants of original settlers, thosewho arrived in antebellum America, and the newly arrivingimmigrants who represented a more linguistically andethnically diverse and marginalized European population.The U.S. Census classified individuals as “native,” “white,”or “foreign-born.” The population of the United Statesbetween 1790 and 1900 grew from 3.9 million to 76.8million, with a foreign-born/immigrant population growthfrom 35,000 in 1790 to over 28 million in 1900. The urbansocial landscape became a patchwork of ethnic enclaves inthe cities, where the recent immigrants lived, and growingsuburban communities just outside the cities, whereupwardly mobile middle-class families settled.In addition to immigrants from foreign countries, rapidindustrialization after the Civil War attracted recordnumbers of Americans from the rural areas of the Southand Midwest to cities. New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio,Illinois, and Missouri ranked as the five most denselypopulated states up to 1890. The most populous cities wereNew York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, St. Louis,Boston, Baltimore, San Francisco, Boston, Cincinnati, andCleveland. The westward movement was especially evidentin the growth of population in Chicago, which increased118 percent in the decade between 1880 and 1890. Overall,the urban population of the United States grew from justover 11 million to just over 18 million in this single decade.For the unskilled working class, the industrial boomconcentrated more and more people in unhealthy livingconditions in cities. Discrimination against immigrantswas a factor in where they could live. By 1893, 70 percentof those living in New York City lived in multi-familydwellings, many of them defined as tenements. Tenementswere apartment buildings with communal water suppliesand sanitation facilities. Entire families lived in oneapartment with little access to fresh air. This resulted inunhealthy living conditions, documented most famouslyin Jacob Riis’s book of photographs of the tenementstitled How the Other Half Lives, published in 1890. Othersconcerned with the living conditions of the working classincluded Jane Addams, who created the Hull-House inChicago, where immigrants could receive education and jobtraining aimed at improving their plight.An Exhibition Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections5

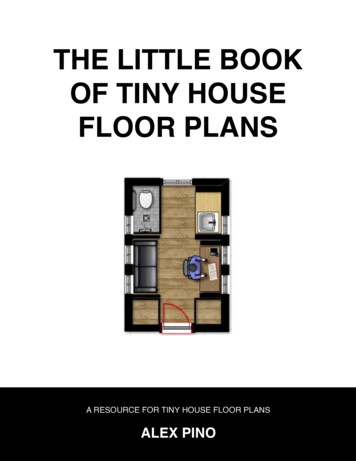

House plans from M.F. Cummings and. Miller’sArchitecture: Designs for Street Fronts, SuburbanHomes, and Cottages, 1865.For the middle class, the post-war industrial boom providedopportunities for housing in suburbs located just outside thedisease-ridden cities and newly accessible via streetcars andtrollies. Men employed in middle management positions—in fields like accounting, retailing, banking, and shipping—could afford to build single-family homes where their wivesand children would be safe and where they could showoff their economic success. Having such a home becameboth a symbol for achieving the American dream and alsoan indication of the innate morality of the hard-workingChristian families who lived there.Many immigrants found employment as domestic servantsin the large homes of the burgeoning middle class wherethey took jobs assisting the women with household choresand childrearing. The architecture of these homes includedservants’ quarters, usually segregated from family spaceswith separate entrances.Fueling the demand for middle-class homes were, of course,the architects and builders who designed and built housesfor this growing market. Their designs were based upon aVictorian view of women and the family. The home becamethe expression and embodiment of the role of women insociety as defined by the Cult of Domesticity and truewomanhood.6House and Home: The Intersection of Domestic Architecture and Social History, 1870-1970WOMEN AND HOMES IN THEVICTORIAN ERAThe “Cult of Domesticity” was first suggested as theappropriate role for women in the early 1800s and wouldcome to be the dominant societal view by the late 19thcentury. Whereas in previous eras men and women workedtogether because many industries were home-based, theincreasing industrialization and urbanization of Americaresulted in the idea of two different “spheres” for thesexes. Men left the home for employment, and the outsideworld came to be seen as male-dominated, logical, andcompetitive. Women, who were seen as naturally moremoral and emotional yet weaker than men, served as theguardians of the home.As the “angel of the house,” a middle-class Victorian womanwas to maintain a pleasing home that provided a respite forher husband from the grueling, capitalist world outside. Shewas also responsible for instilling Christian values in herchildren, ensuring that they would serve as moral, productivecitizens in the future and thereby strengthen the countryand insure its destiny. The Cult of Domesticity was heavilypromoted by religious leaders, social reformers, and advicebook writers. Being able to maintain the “perfect” homecame to be seen as the highest ideal a woman could achieve,and domestic manuals, such as those written by CatharineBeecher and Lydia Maria Child, attempted to glorify the roleof wife and mother as the most powerful force in the home.The family unit was seen as sacred and as the foundationupon which the prosperity of the country rested.

These ideals extended to housing design. An example was ahousing concept developed by Catharine Beecher and hersister Harriet Beecher Stowe. This house included Gothicfeatures such as bay windows and gables adorned with crossesto emphasize the concept of the family home as small church.Because efficiency was considered a Christian virtue, eventhe layout of the basement was designed so that the effort ofhauling coal, water, and ice (for the icebox) was minimized.This design, combined with the latest technologicalinnovations, was seen as the ideal home for a Christian family.The physical location of the home in Victorian America wasalso intended to emphasize the importance of being a safehaven from the outside world. As cities grew larger, theywere seen as sources of filth, noise, and corruption. Newerhomes on the outskirts of cities meant families could livein peace but were still within commuting distance. Theseparation of the suburban home from the increasinglycrowded cities allowed families the privacy they neededin order to engage in recreational activities. Landscapingreflected this ideal as suburban homes were also designed toemphasize the connection to the natural world. Front lawnscreated ribbons of green up and down streets, and porchesopened the house to the outdoors.The home became not just a place of refuge from thechaos of the cities but increasingly a vehicle for womento express their creativity. Since women were thought tonaturally possess a greater appreciation for art and beauty,they were now also tasked with ensuring that their homeswere aesthetically pleasing. By emphasizing the artisticelements of homemaking, housewives sought to increasethe importance of the work they did. The emphasis onaesthetics also resulted in an increased focus on a family’spossessions; sofas, fancy wallpapers, patterned rugs, andother household furnishings gave rooms a sense of opulence.Handmade embellishments enhanced the interior design.Self-improvement and self-expression became one of themost significant characteristics of the Victorian Americanfamily.The post-Civil War period saw the transformationof America into an enormous corporate unit, broughtabout by the expansion of technology and media such asrailroads, newspapers and magazines, and the telephoneand telegraph. In addition, the growth of factories resultedin the mass production of goods at cheaper prices. Theavailability of ready-made items, new labor-saving devices,and the practice of immigrant women performing muchof the domestic work all presented a challenge to women’saccepted role. Furthermore, as women became increasinglyeducated, they began looking for an outlet for their talents.These changes resulted in a revised ideal of the middle-classVictorian woman in the last years of the nineteenth century:that of the “professional” homemaker. Domestic manualsof the time reflected these ideals. Fields such as chemistry,medical science, nutritional science, and psychology werenow applied to every domestic task, from cleaning thehome to preparing food and raising children. Some collegeeducated women, denied entry into the traditionally malesphere, found status and influence as arbiters of professionalhousekeeping standards.PATTERN BOOKS PROMOTETHE VICTORIAN IDEAL OF HOMEPlans for Victorian “cottages” from A. J. Bricknell.To design houses that fit Victorian ideals of woman andfamily demanded a new kind of home and a new kind ofperson to build it. The Greek Revival home that had beencommon among the upper class in the late 18th and early19th centuries was replaced by the Gothic Revival home.Gothic Revival houses were built with a new constructionAn Exhibition Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections7

An early example of the pattern book is Samuel Sloan’s TheModel Architect: A Series of Original Designs for Cottages,Villas, Suburban Residence, Etc., published in two volumes in1852. The book includes enlarged details of Sloan’s houses,along with lithographs of fully executed designs for ruralresidences shown within their environment. The book alsomakes clear the connection between a man’s house and howhe is perceived by his acquaintances: “A man’s dwelling, atthe present day, is not only an index of his wealth, but alsohis character,” Sloan states in his introduction. He alsooutlines the sentiments that will influence home designthroughout the Victorian period: “Around this spot all thethoughts and affections circle. Here is rest. If peace nothere, it will not be found on earth . Indeed, all that ispure in human nature, all the tender affections and gentleendearments of childhood, all the soothing comforts ofold age, all that makes memory a blessing, the presentdelightful, and gives to hope its spur, cluster around thatholy place—home.”Plans for Victorian “cottages” from Palliser and Company.method pioneered by architect Andrew Jackson Downingcalled the “balloon frame.” Downing’s book TheArchitecture of Country Houses, published in 1856, containednumerous examples of country cottages that could be builtrather cheaply if builders used his building techniques.The balloon frame focused the weight of the home on theexterior walls, with interior walls made of lighter framing.Despite being lighter, the houses were stronger, and theycould be designed with complex roofing systems thatincluded steeply pitched roofs, sharply pointed dormers, andornamentation on the gables. The home design reflectedelements of ecclesiastical architecture, thus creating afeeling of the house as a holy sanctuary for the family. Somedesigns even incorporated stained glass to enhance thefeeling of the home as place of worship.To sell these homes, architects used pattern books depictingplans for homes, oftentimes showing what the house wouldlook like within its landscaped setting. Pattern books, whichwere published by the thousands in the latter half of the19th century, allowed those who wanted to build such ahome to bypass architects and instead employ builders. Thebuilders could purchase the plans directly from the patternbook publishers.8House and Home: The Intersection of Domestic Architecture and Social History, 1870-1970Sloan’s houses, like most of the Victorian era, includedboth public and private spaces. The dominant feature of thefirst floor was the hallway, the primary public space, whereguests would be greeted. It usually contained an ornatehallstand where hats and coats of guests could be placed andcalling cards left. Since it was the first piece of furniture aguest would see, it was generally ornate and expensive. Theparlor and dining rooms on the first floor were also intendedas the public spaces. The parlor was one of the mostimportant rooms; here guests were entertained with games,music, and conversation. A fireplace with an elaboratemantle usually dominated the room. The kitchen was atthe back of the home and not intended as a public space.Bedrooms and chambers, where family life occurred outsidethe public realm, were located on the upper floors. Thesefloors were the woman’s sanctuary, where she fostered thedevelopment of her children and supported the needs of herhusband. Since Sloan’s houses were intended to be cottages,they often did not include servants’ residences. If homesincluded quarters for servants, those were accessed throughback hallways out of public view. In later years, manyfrom the working class found more lucrative employmentin factories, leading to a sharp decline in the number ofdomestic servants employed in middle-class homes and theelimination of servants’ quarters.One of the first pattern books clearly aimed at potentialowners and builders and not architects was Architecture:Designs for Street Fronts, Suburban Houses, and Cottages, byC.C. Miller of Toledo and M.F. Cummings of Troy, New

York, published in 1865. Rather than include completearchitectural plans of homes, the Miller and Cummingsbook contained drawings of details of buildings suchas entryways, cornices, roofs, and gables. As stated inthe introduction, “This work will be found particularlyvaluable in situations where it is not convenient to securean architect; in such locations owners and their builders areusually thrown upon their own resources of knowledge as towhat is good and proper taste to introduce into the designof the building they propose to erect . If they possess awork in which every needed architectural feature, boththose of utility and those of ornament, is given, necessary tocomplete construction of the building, it will be a difficulttask to make the structure a good-proportioned and invitingone.” The end of the book includes full facades of suburbanhomes that could be constructed by combining the variouselements detailed in the book. The architects also advertisedthat they would sell plans for the elements if builders wishedto purchase them.Soon, pattern books were a flourishing market. One ofthe most popular was Palliser’s American Cottage Homes.The book was printed on cheap paper and sold for 25cents. Readers could select the home they liked andpurchase plans directly from Palliser. The back of thebook included advertising from local suppliers. Thedesigns covered everything from simple “workingman’scottages” to 12-room, brick mansions. Palliser’s designsfeatured the later stages of Gothic Revival, a style knownas Queen Anne. Queen Anne is perhaps best described aseclectic Gothic, with many design elements thrown togetherin an effort to design ever moreelaborate homes in order to show offthe owner’s success. They includedlarge front porches, turrets, towers,different types of shingles and siding,and many styles of roofs, all on onehouse. Builders were encouraged notto try to build the homes withoutpurchasing Palliser’s plans: “Without working drawings, it isimpossible for any builder to carry out the spirit of a designand the detail as intended by the designer, much less makealterations to suit the requirements of different individualwants without marring the design,” the book stated.Other popular pattern book publishers included A. J.Bricknell. In addition to their own pattern books, theyalso published those by architect Daniel Wood and thePallisers. The fact that Bricknell was successful specializingin pattern books provides some indication of the popularityof these volumes and their influence on American domesticarchitecture.By the turn of the 20th century, social critics began toquestion the appropriateness of the Victorian home. Manyfelt they were too large, too ornate, with too many roomsand too much clutter. Women also began to question theirrole in society as the keepers of the home and hearth. Somebecame social activists, taking on causes like the dangers ofalcohol and the right to vote. They also sought a less formal,more comfortable family life, and a new style of house thatwould allow them more time for activities outside the home.Catharine Beecher and Harriet BeecherStowe’s The American Woman’s Homewas one of the most popular domesticmanuals attempting to instruct women onhow to manage their home appropriately.An Exhibition Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections9

Examples of the dark color pallet and elaborate wallpaperdesigns that adorned Victorian homes.Constance Cary Harrison’s Woman’s Handiworkin Modern Homes included patterns for creatingmany handcrafted “embellishments” to decorate theVictorian home.How to Build, Furnish, and Decorate, published in 1882, includedadvice on creating the perfectly embellished Victorian interior.10House and Home: The Intersection of Domestic Architecture and Social History, 1870-1970

Selected Item DescriptionsIMMIGRATIONRiis, Jacob A. How the Other Half Lives: Studies Amongthe Tenements of New York. New York: Charles Scribner’sSons, 1890.A stunning indictment of the plight of the poor immigrantin New York City, Riis supplemented his vivid languagewith photographs of living conditions in the tenements.While middle-class Americans were contemplatingbuilding large Gothic Revival homes by perusingarchitectural pattern books and trying to lead lives asoutlined in the many domestic manuals of the day, theworking class was simply trying to survive in crowded,squalid buildings with little fresh air and poor sanitation.Living conditions in the tenements allowed diseases tospread quickly, and encouraged those who could tomove to the suburbs where single-family homes wereperceived to be healthier.Riis, Jacob A. The Battle with the Slum. New York:MacMillan Company, 1902.A sequel to How the Other Half Lives, this book wasan optimistic view of efforts made by Progressive-erapoliticians to improve the living conditions of the poorliving in city tenements. The inside cover included alithograph of Theodore Roosevelt, with the title “A ValiantBattler of the Slum.”Addams, Jane. Twenty Years at Hull-House, withAutobiographical Notes. New York: MacMillan Company,1925.A second edition of Addams’s classic work of 1910, thisvolume was signed by the author. It outlined her struggleto provide education and opportunity to the immigrantsof Chicago, including better housing.Antin, Mary. The Promised Land. Boston, New York:Houghton Mifflin Company, 1912.A first-person account by a Jewish immigrant fromPolotzk, Belarus who settled in the West End of Boston.She described her new accommodation as superiorto that in the homeland, even though by middle-classAmerican standards the apartment buildings were notattractive.DOMESTIC MANUALSEastlake, Charles. Hints on Household Taste. London:Longsman, Green, 1868.Charles Eastlake was an architect and furnituredesigner who believed most people lacked the abilityto distinguish good design from bad. In his book, heproposed guidelines for understanding interior design.His book was so popular, especially among womenintent on creating a stylish home, that his name becamesynonymous with the Eastlake style of furniture of theVictorian era.Beecher, Catharine E. and Harriet Beecher Stowe. TheAmerican Woman’s Home: Or, Principles of DomesticScience. New York: J.B. Ford and Company, 1870.While hundreds of titles were published in the post-CivilWar period that attempted to direct women how toappropriately care for their home and family, accordingto society’s prescribed expectations, this book wasperhaps the most important. Written by the author ofone of the century’s most influential works of fiction andher sister, it was dedicated to “the women of America,in whose hands rest the real destinies of the republic,as moulded by the early training and preserved amidthe mature influences of home.” It included instructionson cooking, cleaning, directing servants, and sewing,among other topics. It also included extensiveinformation related to the need for adequate ventilationin houses to insure the health of the family. One chaptereven described how to construct and operate an “earthcloset,” which was an early version of a compostingtoilet.Dresser, Christopher. Principles of Decorative Design. NewYork: Cassell Petter & Galpin, 1873.Following the success of Eastlake’s book, many otherguides to interior design were published. This oneincluded beautiful colored illustrations showing the richpallet of Victorian design.Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1870s to 1880sOne of the most popular magazines aimed atmiddle-class women of the time, Godey’s Lady’sBook included articles on fashion, instructions forcreating “embellishments” for the home, recipes, andarchitectural drawings of houses, along with examples ofcurrent literature. Colorized lithographs showed interiordesigns for public spaces of Victorian homes.Cook, Clarence. The House Beautiful. New York: Scribner,Armstrong, and Co., 1878.Originally published as a series in Scribner’s Monthly,The House Beautiful expounded on the idea of simplehome

Oct 19, 2016 · sold in catalogs as kits, magazines showing trends in interior design, and advertisements enticing us with the latest in home innovation. Most of these outlets that promoted the perfect home and . therefore the perfect family and perfect life were—a