Transcription

U N I V E R S I T Y O F MARYLAND, BALTIMORE/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINES2010

2

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESCONTENTSOVERVIEW3CONTEXTUAL IDENTITY7SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES11SITE DEVELOPMENT21ARCHITECTURAL GUIDELINES29PRECINCT STUDIES37LANDSCAPE GUIDELINES63

2

SECTION 1 / Overview3

4

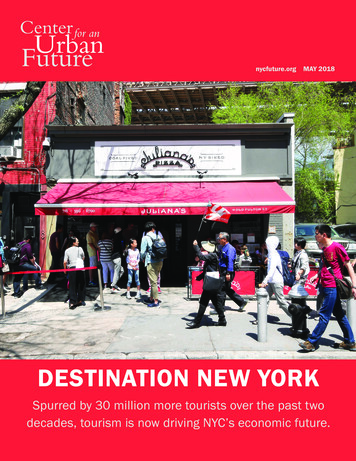

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESOVERVIEWThe design guidelines contained within the 1991The Guidelines are not intended to prescribe solutionsFacilities Master Plan and the subsequent 1996 andor limit creativity, but rather, to establish a flexible2002 Facilities Master Plans have been a designframework that respects UMB’s past, addressesreference for the University of Maryland Baltimore forits present needs, and encourages innovation inalmost two decades. The sheer quantity of completedthe future. This document refines developmentprojects realized under these documents underscoresopportunities for the University’s buildings andtheir importance. As with any institution, however,grounds, providing a series of recommendations forcircumstances within and around the Universitythe following tating the Guidelines to respond in turn. Sense of place SustainabilityThis document, known as UMB’s Urban Design Site developmentGuidelines or “the Guidelines,” revises previous Architectural guidelinesrecommendations, with expansion mainly in the Streetscapesarea of sustainability. In addition, this document Open spaceconsolidates multiple reference guidelines into one Urban horticulturevolume to be the primary resource for future building Landscape standardsand grounds development on the UMB campus.The Guidelines are an integral part of the 2010Purpose of Design GuidelinesFacilities Master Plan Update, and together theyThe UMB campus, as it has evolved over the past 200define the goals and principles that will guide theyears, possesses a unique, urban quality, characterizeddevelopment of the University. As future projects areby the density and scale of its schools and buildings,implemented, the identity of the campus environmentpalette of materials, preservation of older structures,will be reinforced with streetscape elements, a strongand relationship to non-University buildings andbuilding presence, an enhanced network of openhistoric districts within the City of Baltimore. Thespaces, and recognizable gateways. These featuresGuidelines ensure that the quality and relationshipswill create a collegiate and memorable sense of place.within the built environment continue to support themission of the University well into the future.5

6

SECTION 2 / Contextual Identity7

The boundaries of UMB in red. The Inner Harbor can be seen in the far, bottom right cornerHistoric Davidge Hall fronting Lombard Street8The Rieman Block (Lexington Street) is a historic collection ofbuildings listed on the National Register. Pascault Row can beseen in the background.

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESCONTEXTUAL IDENTITYThe University of Maryland Baltimore enjoys aout in 1799. The cemetery provides an invaluable linkhistorically rich and urban setting that lends theto the people responsible for the initial development ofcampus much of its physical identity. Building andthe City of Baltimore. Westminster Cemetery, adjacentopen space projects on campus will respect andto the University’s Law School, is the burial site ofstrengthen the contextual identity of the University’sEdgar Allen Poe. It is common to see roses, brandy,campus.and pennies left at his grave stone. Pascault Row,on Lexington Street, is the last remaining exampleHistoric Fabricof early 19th century townhouses in Baltimore.The campus has matured over two centuries, withThe Rieman Block, at the southwest corner of Westeach new building added in a way that expresses theLexington and Pearl Streets, records a post-Civil Warculture and influences of that particular time in history.Baltimore. The North and South Loft historic districtsThere are thirty-two campus properties that have beeninclude nineteen manufacturing buildings dating tosurveyed and analyzed for historical significance;an era between 1870 and 1915. Architecturally, thesetwenty-seven have been categorized as standingbuildings are stunning. Culturally, they capture thestructures and three as below ground (archeological)history of Baltimore’s garment industry that grew tosites. The University either falls within or abuts threenational renown. Another adjacent historic district,different National Register Historic Districts, includingMarket Center, is comprised of row houses, smallMarket Center, the Loft District (north and south), andcommercial buildings, churches, schools, hotels,Ridgley’s Delight.department stores, and chain stores that display theevolution of the City over a 100-year period. SpurredThe history of these buildings and districts is rich. Forby the activity of Lexington Market in the 19th century,example, Davidge Hall, named after the first dean of thethe area evolved from a small-scale urban residentialCollege of Medicine of Maryland, is the oldest buildingneighborhood into the City’s premier, early 20thin the United States in continuous use for medicalcentury shopping district. The district also chronicleseducation. Because public opinion at the time of itsthe decline of urban retail centers within post WWII,construction violently condemned human dissection,automobile-oriented development patterns.Davidge Hall’s dissection labs were hidden withinthe building, below the sloping seats of the lecturehall and the rectangular outer walls. Secret spiralstaircases led to these rooms. St. Paul’s Cemetery, atRedwood and Martin Luther King Boulevard, is thesecond oldest cemetery in Baltimore, originally laid9

Future campus projects shall retain, to the greatestextent possible, the historic features within campus.Keeping the historic fabric intact ensures a strong,recognizable identity for the campus and a linkto history that enriches both University and Cityneighborhoods. UMB projects shall seek compatibleuses for historic buildings either currently ownedor acquired in the future. The University’s HistoricPreservationPlancomplementsthisdocumentand provides further guidance concerning newconstruction, renovation, and adaptive reuse ofhistoric structures.The gate to St. Paul’s Cemetery, the second oldest cemeteryin Baltimore.29 South Paca Street, the former Strouse & Brothers Buildingbuilt in the late 1800sThe burial place of poet and author Edgar Allan Poe, adjacentto the Law School.10

SECTION 3 / Sustainable Practices11

12

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESSUSTAINABLE PRACTICESBuilt EnvironmentThe University’s leadership, by signing the Ameri-Building design today is a more integrated processcan College and University Presidents Climate Com-than ever before. The classic elements of form,mitment (ACUPCC) in 2007, has shown its intentionfunction, materials, and site orientation will be appliedto minimize the carbon footprint of the campus. As ain concert with the latest technologies and innovationssignatory of this commitment, the University pledgesto optimize a building’s long-term performance. Eachto develop an institutional action plan that achievesbuilding must balance culture, history, function,climate neutrality, and future campus projects willmaterial use, and technology in a setting that respectsadhere to the benchmarks and recommendations out-the capacity and parameters of the site.lined by that plan. The recommendations set forth inthese guidelines are part of the same concerted effortThe University prioritizes adaptive reuse of existingto support the climate action plan.buildings as a means to minimize its carbon footprintand reduce the consumption of raw materials.In the broadest sense, the University seeks to createIn addition, new construction projects will studya campus environment that actively improves theapplicable opportunities for solar, wind, geothermal,quality of life and the environment for its users.and heat recovery systems as a means to reduceUniversity operations will address sustainability as aand/or generate energy on campus. LEED Guidelinescontinuous process affecting environmental, social,shall be used for determining appropriate buildingand fiscal concerns. Sustainable practices occur at allperformance levels.scales -- from the city and campus, to buildings andlandscapes, to products used within those buildings.Designers shall reduce impervious surfaces andThese Guidelines direct sustainable practices at theencourage green landscapes with new projects.“campus scale” by addressing goals within four broadThey should incorporate innovative stormwatercategories: the built environment, energy, ecologymanagement practices into the building design.and hydrology, and sustainability education.Likewise, designers shall incorporate alternativemeans of access (i.e. bicycle, public transit, etc.) intothe building’s design to limit the impact to the existingroad network and reduce the need for personalvehicles. Bicycle storage space and showers, andfacilities to accommodate use of public transportationare all examples of elements that shall be explored incampus projects.13

Individual building projects shall be integrated intoProjects shall employ an integrated design approacha sustainable campus network. This requires thatwith whole-systems life cycle evaluations. Equipmentthe designer pay particular attention to existingselection must be coupled to operational performancesite infrastructure such as utilities, roadways, andrequirements to minimize building energy loads.pedestrian paths. In addition, both the University andBuilding projects should integrate innovative designthe designer must test appropriate capacity of the siteand engineering solutions at project inception, so thatto ensure that introducing a new infill project does notthe design supports energy conservation initiativescreate a burden to the surrounding area.outlined in the University’s energy master plan.EnergyThe aesthetics of sustainable buildings are differentRenovations and new construction projects shall befrom traditional campus buildings. Likewise, thedesign to reduce the energy consumption of buildingsuser’s interaction with these buildings will alsoand their mechanical, electrical, and plumbingchange. This new, evolving design language is onesystems (HVAC, hot water, bathroom fixtures, andthat the University embraces in support of its climatelighting) by using appropriate high efficiency andcommitment.energy conserving equipment with digital monitoringsystems. As well, designers shall integrate fresh airventilation, natural daylighting, and passive solardesign into building projects. The University willevaluate the use of new technologies as they becomeavailable and affordable.14

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESLight shelf on the School of DentistrySunshade at the Sidwell Friends School in Washington, DCSunshade at Messiah College in Grantham, PennsylvaniaSolar panels at Emory University15

Ecology and HydrologyEven in a dense urban area, a university campusfunctions as a dynamic natural space that plays hostto smaller eco-systems while also connecting to thewider ecology of the region around it. As such, UMBwill act within its power to honor and connect habitatand stream corridors within the Patapsco River basin,which drains into the Chesapeake Bay.The streams that run through the campus are belowground; however, new projects shall be sensitiveto the ways in which stormwater run-off affectsthose downstream. The University will strive toStormwater inlet collects, filters, and detains run-off, Portland,ORact responsibly to protect this shared resource.Building and landscape design must actively addressstormwater management issues of both quantity andquality of runoff. As well, UMB will reduce potablewater demand through conservation, reuse, andrecycling. New building projects shall meet or exceedCity requirements.By connecting the campus’s open spaces into anetwork of green around the campus (“rings ofgreen”), the University will create small-scale wildliferefuges for songbirds and beneficial insects on itsgrounds. In a highly urbanized area, this becomesan important function. The University will encouragecampus connections to the larger region throughsupport of greenways, fitness walks, bicycling trails,building courtyards, and rooftop gardens.16Native grasses at the School of Dentistry require lessmaintenance and improve stormwater collection on site.

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R EOPEN SPACE PLAN/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINES0100200400u17

As the University develops its physical grounds, itwill ensure that the massing of new buildings allowsdaylight to reach active outdoor spaces. As well, newlandscaping projects on campus shall utilize a paletteof native species that reduce the need for irrigation,chemical treatments, and general maintenance. Byplanting streetscape trees, the University will supportthe City’s commitment to reforestation. It is theUniversity’s intent to create healthy and ecologicallyappropriate open spaces, provide pleasant outdoorenvironments, and minimize stormwater runoff withinits campus.The School of Dentistry walkway softens the building facade,provides color, and is beneficial to birds and insects18

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESSustainability EducationAs a signatory of the ACUPUCC, the University will bea leader in thought and cutting edge technologies thataddress global climate change. New projects shallbe designed to encourage campus users to engagein their surroundings. With proper design, features ofthe physical campus will influence public educationand promote environmental sustainability. Featuringelements of green infrastructure such as rain gardens,cisterns, exposed stormwater runnels/channels, windturbines, roof gardens, pervious pavers, and solarpanels will stimulate curiosity and invite furtherexploration of the campus.“Green Streets” public education program in Portland, ORStormwater runnels in Vera Katz Park in Portland, OR19

20

SECTION 4 / Site Development21

SITE DEVELOPMENTCampus organizationArchitectural guidelines set the requirements for newdevelopment and provide guidance on the shapeand location of campus buildings on available sites,ensuring that a specific project will fit into the largerwhole of campus.This is a general level of architecturalcontrol necessary to create a coherent campusprecinct while accommodating the programmaticneeds of the University.Architectural styles range from Classical Revival(Davidge Hall, 1812) to late nineteenth centurywarehouse buildings, to contemporary high-risestructures. Sense of place is dependent on architecturalcharacter, which is derived from a broad set ofinterrelated visual and spatial properties includingscale, rhythm, proportion, and texture that are bothrespectful and contextual. The Guidelines that followprovide basic principles in support of UMB’s existingarchitectural character.Classic Revival architecture of UMB’s Davidge Hall22The Southern Management Corporation Campus Center is ofa more modern styleExample of historic loft warehouse near UMB

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESBuildings as Edge DefinersCampus buildings will front two types of spaces:streets and open areas. In both situations, buildingswill form an edge that defines the space it abuts. Onthe UMB campus, buildings most frequently define thestreet edge. Each new building should contribute tothe aesthetic of the site and improve adjacent streetsand pedestrian walks. Use of the campus palette forbuilding and landscape materials, walkways, lighting,signage, and street furniture will create an activestreetscape adjacent to the new building. In addition,new buildings should reinforce connections within thecampus and provide enhanced entries, courtyards,The Lexington Street Administrative Building creates a strongedge along both Lexington and Pearl Streets; it is also anexample of a well-designed vertical setback.and landscaped open space when appropriate for thespecific site.Build-to LinesNew construction will extend to eighty percent of theproperty line, with the exception of at-grade setbacksrecommended within this document. A floor-to-arearatio of eight is appropriate for campus buildings.Build-to lines may be relaxed to allow for smallcourtyards, parks, and other open spaces that connectto a larger network of green spaces around campus.These spaces shall be anchored to building uses toensure their care, maintenance, and security.23

SetbacksThere are two recommended setback types: at-gradeThe existing City of Baltimore zoning permits aand elevated. At-grade setbacks balance a strong streetFloor Area Ratio (FAR) of eight times the parcel area.edge with the need for enhanced campus identity andHistorically, the University’s buildings have eithergreen space “relief” in an urban environment. Themet this requirement, or been constructed smallerelevated setback requirement occurs in the central areathan allowed depending on the site and contextualof campus where building heights of 80 feet and higherconditions. New construction shall respect the scale ofare permitted. A minimum 15-foot setback above 65its context, assess the site parameters, and satisfy thefeet in this zone is required. Elevated setbacks are alsorequirements of the program. In addition, site densityrequired when a building, regardless of its height, isshall reinforce a collegiate, pedestrian-friendly, andadjacent to a residential neighborhood. Section 6.0 ofwelcoming environment.these guidelines provides the recommended buildingsetbacks on new construction projects.MINAcceptable vertical setback ranges24

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R EExample of at-grade setback in front of the SouthernManagement Corporation Campus Center/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESExample of at-grade setback in front of the School of Law25

Building HeightProposed building heights (distance from grade toEach new building project is required to have a solarcornice line) will fall into three general ranges:study performed to assess and recognize the impact of 15 to 40 feet: This range is generally adjacent toheight and mass (as cast by its shadows) on adjacentexisting residential neighborhoods, includingbuildings and open space. New buildings shall beRidgely’s Delight, Pascault Row, and residencesdesigned to allow as much daylight as possible towest of MLK Boulevard. Building scale in thesepenetrate the campus and minimize casting shadowsareas shall be smaller to fit appropriately withinon open spaces, important walkways, and neighboringthe context of the neighborhood.buildings. 40 to 80 feet: The predominant building heightin this area ranges between 60 and 75 feet. Newconstruction adjacent to buildings in this rangeshall be responsive to their scale. Above 80 feet: This is the most intensely developedarea of the campus and will continue to be so inthe future. A 15-foot setback shall be created above65 feet to reduce the building’s scale and allownatural light to reach adjacent open spaces.26

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESHOWARD STREETEUTAW STREETPACA STREETGREENE STREETSARATOGA STREETLEXINGTON STREETFAYETTE STREETBALTIMORE STREETLOMBARD STREETPRATT STREETWASHINGTON BOULEVARDKBMLOUDARLEVBUILDING HEIGHTS15 - 40 FT0100200400u80 FT40 - 80 FT27

Access and ServiceBuilding access needs to accommodate pedestrians,The design of new projects must address the safetyvehicular drop-off, emergency vehicles, and serviceof individuals by providing appropriate lighting levelsfunctions. In general, pedestrian and vehiculararound buildings and on campus grounds. Excessivedrop-off should have access through major buildinglight levels create contrast and shadows that shouldentrances located on primary streets or on campusbe avoided. Buildings shall have windows facing theopen spaces. Service access should be separate fromstreet. Plants and physical objects must be selectedthe other uses. To the extent feasible, service accessand designed to remain low to allow for clear visibility.shall be located on the system of alleys and minorFaçade designs at the street level shall avoid niches orroads serving the secondary facades of buildings soplaces of concealment.that their visibility from public areas is minimized.Emergency access should be well marked andobstacle free.SecurityThe University is concerned with the security of itsstudents, faculty, staff, and visitors, and the securityof its buildings and the research contained within.Building security shall be addressed at the inceptionof each project with Public Safety and FacilitiesManagement. Specific opportunities and constraintsshall be identified for each site to ensure that thebuilding design is safe and secure. Street furnishingsmay be used as a form of security at buildingperimeters when appropriate.28The area in front of the University’s Campus Center feels safedue to an abundance of lighting, windows that provide viewsof street activity, well-maintained landscaping, and peopleusing the space.

SECTION 5 / Architectural Guidelines29

ARCHITECTURAL GUIDELINESBuilding TypologyBuilding FormsCampuses are collections of buildings with similarIn cities, buildings tend to be tall, large in footprint,programs representing academic, research, medical,and large in scale. On the UMB campus, scale shall beand support uses. These programs influence acontrolled to minimize the potentially overwhelmingbuilding’s size and location on campus. Groupings ofappearance of buildings from the street or adjacentsimilar uses occur because of a desire to maximizeopenfunctionalsimilarbuildings that function as singular object buildingstypologies. Buildings shall be designed to portray theand do not relate to the urban fabric or characteristicsprograms contained within through characteristicsof the campus. Designers shall also consider arrangingembodied in the building envelope, mass, anda façade into three major vertical elements to create adetailing. For example, laboratory buildings may betripartite that is comprehensible to the human lavoidextrudingcharacterized as having a low surface to glass ratio,tall floor-to-floor heights to accommodate interstitialBaseutility distribution, and roof treatments to concealSelection of materials for the base of buildings dependsfume hood exhaust stacks. Conversely, residenceon the following criteria: durability, maintenance,halls might have higher surface to glass ratios, lowerand graffiti-resistance. It is preferable that buildingsfloor-to-floor heights, with simple and efficient façadefronting the principal streets and pedestrian spinesand roof details. The incorporation of sustainablehave stone bases in order to distinguish it at streetdesign practices, including the beneficial increasedlevel. The stone shall be light in color and relate touse of glazing for natural daylight, may affect thosethe limestone used on other campus buildings. Bricktraditional characteristics.is also an acceptable material for the base portion ofbuildings when detailed to differentiate it from theupper levels.30

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESMiddleTopThe primary material of the walls above the baseBuildings in the above 80 feet zone shall employshall consist of standard-size indigenous red/pinkmaterial changes to produce a landmark silhouette andbrick, traditionally associated with the architecturevaried skyline at the center of the campus. Buildingson the UMB campus. Varying brick sizes may be usedoutside the above 80 feet zone shall incorporatefor decorative purposes and/or on secondary wallsrooflines that are contextual to the identity of theinternal to the site. Stone is also an acceptable wallcampus. The top of the building shall be composed ofmaterial if the significance of the building and thematerials and form as to be clearly discernible frombudget allow its use. Designers shall consider thethe middle section.compatibility of brick and stone colors of adjacentbuildings during the design of the new facility. Thisshould not, however, discourage visual richness on thecampus. Window frames and mullions, sunscreens,reflectors, shading devices, metal panels, and railingsmay be used to introduce color into building facadeswhen appropriate. Larger expanses of glass andvariations in materials will be reviewed on a projectby-project basis, when alternative materials enhancethe performance of a sustainable, energy efficientbuilding.School of Medicine31

Roofs for low buildings function as a fifth façade. Inthese instances, rooftop terraces or other reen roofs, where used, shall be integrated intothe stormwater management systems of buildings.Materials and paint colors shall be specified whichreflect the light and heat from the sun; however,materials should not produce a glare toward adjacentbuilding occupants. Metal on roofs shall be painted,when appropriate. Unless aesthetically designed tobe visible, mechanical equipment shall be screened.As the University pursues campus-wide sustainabilityefforts such as LEED certification and enhancedbuilding performance, both the function and look ofits buildings will change. UMB is an urban campusthat consists of a range of building styles. Withproper design, many building functions – stormwatertreatment, solar collection, etc. – will serve a dualpurpose of enhancing a building’s performance andits visual appeal.FenestrationThe placement and size of the fenestration for afacade generates hierarchical patterns and rhythmsthat are visually stimulating and contribute to theoverall building aesthetic. Openings (doors, windows,and loggia) reduce the perceived scale of a buildingby dividing continuous wall surfaces into smaller,more comprehensible parts. The Guidelines limitlarge expanses of solid wall surface or continuousglass curtain walls. When such a condition does occur,Across campus, roof styles span a century’s worth ofarchitectural styles.32

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESwalls shall be carefully detailed and articulated. Theuse of tinted or reflective glass is not allowed; frettedglass for sun control is permissible.WindowsWindow openings shall be vertically oriented (orarticulated as such by use of frames and mullions),and generally consist of masonry or stone heads andsills where appropriate. Ample fenestration at thebase of a building will maximize visual connectionsbetween the ground level of the building and theadjoining open space. Double-skin glazing and otherinnovative window wall systems shall be considered ifthey enhance the energy performance of the building.Academic activities within the building shall be visiblefrom the exterior whenever possible to enhance thestreetscape of the campus and promote security.Examples of campus window fenestration; styles range fromtraditional to modern33

Examples of building entriesEntriesArticulation of the main public entry of the building isEntrances shall be visible to visitors and contributecrucial for promoting clear visual and intuitive accessto the life and activity of the streets and walksto campus buildings. Architectural elements that instillsurrounding the building. These spaces shall bea sense of hierarchical importance will enhance thedesigned to encourage interaction as meeting andprimary entry of buildings. Canopies, loggias, changegathering places. Well lit and glass entries providein vertical plane, change in grade, change in material,unobstructed site lines to the sidewalk and enhanceand placement of signage highlight and distinguish acampus security. Building vestibules, as weatherbuilding’s entry.breaks, prevent heat loss and gain and minimizedrafts to the interior spaces of the building.All building entries shall provide a transitionalspace between the public street and private buildingenvironments.34

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M A R Y L A N D , B A LT I M O R E/URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINESPredominant MaterialsThe University has an established palette of materials,consisting of brick, stone, and glass. By respecting thispalette, new building designs will foster a sense ofarchitectural continuity with existing buildings. Otherapproved materials may be employed to highlightparticular features of the façade, and the Universityencourages designers to use these accent materialsin a way that explores and expands upon the basicvocabulary of the brick campus building. The interplayof materials and textures with the traditional buildingpalette respects the campus’ historic building styleswhile creating a modern aesthetic.Examples of the materials found in UMB’s material palette35

36

SECTION 6 / Precinct Studies37

PRECINCT STUDIESThe Guidelines divide the campus into sevenprecinct areas of study based on locations where theUniversity expects new construction in the next five totwenty years (as outlined by the 2010 Facilities MasterPlan Update). The following section makes specificrecommendations for building height and mass, setbacks and build-to lines, site open spaces, primaryentrances and service access within each precinct.The precinct areas include surrounding buildings, notjust the parcel targeted for development, so that thearea is seen in context.38

U N I V E R S I T Y O F M

Guidelines or “the Guidelines,” revises previous recommendations, with expansion mainly in the area of sustainability. In addition, this document consolidates multiple reference guidelines into one volume to be the primary resource for future building and grounds development on the