Transcription

Teaching ListeningEkaterina Thomas S. C. Farrell,Series Editor

Typeset in Janson and Frutigerby Capitol Communications, LLC, Crofton, Maryland USAand printed by Gasch Printing, LLC, Odenton, Maryland USATESOL International Association1925 Ballenger AvenueAlexandria, Virginia 22314 USATel 703-836-0774 Fax 703-836-7864Publishing Manager: Carol EdwardsCover Design: Tomiko BrelandCopyeditor: Jean HouseTESOL Book Publications CommitteeJohn I. Liontas, ChairMaureen S. AndradeJoe McVeighJennifer LebedevGail SchafersRobyn L. Brinks LockwoodLynn ZimmermanProject overview: John I. Liontas and Robyn L. Brinks LockwoodReviewer: Soonyoung Hwang AnCopyright 2013 by TESOL International AssociationAll rights reserved. Copying or further publication of the contents of this work arenot permitted without permission of TESOL International Association, except forlimited “fair use” for educational, scholarly, and similar purposes as authorized byU.S. Copyright Law, in which case appropriate notice of the source of the workshould be given.Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders for permission to reprint borrowed material. We regret any oversights that may have occurred and willrectify them in future printings of this work.ISBN 9781942223030

ContentsPreface. v1Introduction. 12What Do Teachers Know About Listening?. 23How Can Teachers Teach Listening? . 114Using Texts and Designing Tasks . 215Teaching Listening With Technology. 346Conclusion. 38References. 40Suggested Readings. 40iii

About the AuthorEkaterina Nemtchinova is a professor of Russian and TESOL atSeattle Pacific University in the United States. Her publications focuson technology in language learning, teacher education, and the issuesof nonnative-English-speaking professionals in TESOL. She is theauthor of Listen Up!, a Russian listening and speaking textbook.iv

Series Editor’s PrefaceThe English Language Teacher Development (ELTD) Series consistsof a set of short resource books for ESL/EFL teachers that are writtenin a jargon-free and accessible manner for all types of teachers of English (native and nonnative speakers of English, experienced and noviceteachers). The ELTD series is designed to offer teachers a theory-topractice approach to English language teaching, and each book offersa wide variety of practical teaching approaches and methods for thetopic at hand. Each book also offers opportunities for reflections thatallow teachers to interact with the materials presented. The books canbe used in preservice settings or in-service courses and by individualslooking for ways to refresh their practice.Ekaterina Nemtchinova’s book Teaching Listening explores different approaches to teaching listening in second language classrooms.Presenting up-to-date research and theoretical issues associated withsecond language listening, Nemtchinova explains how these newfindings inform everyday teaching and offers practical suggestions forclassroom instruction. The book thus provides a comprehensive overview of the listening process and how to teach listening in an easy-tofollow guide that language teachers will find very practical for theirown contexts. Topics include the nature of listening, listening skills andstrategies, how to teach listening, using texts and tasks, and teachinglistening with technology. Teaching Listening is a valuable addition tothe literature in our profession.I am very grateful to the authors who contributed to the ELTDSeries for sharing their knowledge and expertise with other TESOLprofessionals because they have done so willingly and without anyv

compensation to make these short books affordable to language teachers throughout the world. It was truly an honor for me to work witheach of these authors as they selflessly gave up their valuable time forthe advancement of TESOL.Thomas S. C. Farrellvi

1IntroductionListening is a crucial part of daily communication in any language. Itaccounts for half of verbal activity and plays a vital role in educational,professional, social, and personal situations. It is also an extraordinarilycomplex activity that requires many different types of knowledge andprocesses that interact with each other. When asked which is more difficult in a foreign language, speaking or listening, many people wouldchoose listening. Many teachers consider teaching listening challenging because it is not clear what specific skills are involved, what activities could lead to their improvement, and what constitutes comprehension. Students are also frustrated because there are no rules that onecan memorize to become a good listener. The development of listeningskills takes time and practice, yet listening has remained somewhatignored both in the literature and in classroom teaching.According to Nation and Newton (2009), it has been “the leastunderstood and the most overlooked of the four skills (listening, speaking, reading, writing) until very recently” (p. 37). A current surge ofscholarly interest in the nature of listening and existing approaches toclassroom practice has brought about important new developments inthe field. This book discusses up-to-date research and theoretical issuesassociated with second language listening, explains how these newfindings inform everyday teaching, and offers practical suggestions forclassroom instruction. Reflective Breaks scattered throughout inviteyou to pause, close the book, and consider these ideas in your owncontext as well as examine your approach to teaching listening.1

2What Do TeachersKnow About Listening?Reflective Break How would you define listening? Is it the same as hearing?If your definition of listening refers to such concepts as interpretation,meaning, or comprehension, you have managed to capture its complexnature. When people listen, they interpret the incoming sounds andpick up important words from the flow of speech to construct meaning.They also make guesses about what they are going to hear next andcheck the new information against their predictions and knowledge ofthe world. Listeners use strategies to cope with difficulties of listeningin real time. They try to remember at least part of what they heard andprepare an appropriate response in the case of face-to-face interaction.These processes are not separate; they happen simultaneously in thelistener’s mind and are interrelated with each other. This is why listening is described as an active skill: although their efforts are invisible,listeners have to work very hard to make sense of the aural input.As a person hears a message, it enters the sensory memory, where itis stored in its original form for about a second. In this time, the braindistinguishes it from other noises, recognizes words of the language,groups them together, and either forwards the input to the short-termmemory or deletes it depending on the quality, urgency, and source ofthe sound. The short-term memory keeps the input for a brief periodto analyze it against the listener’s existing body of knowledge. After themessage has been understood by associating it with or d ifferentiating2

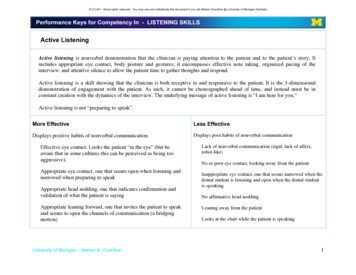

it from the other information, it can be retained in the long-termmemory forever. The brain, memory, and speech recognition processesare included in the cognitive dimension of listening (Vandergrift &Goh, 2009).Equally important is the social dimension of listening, whichaccounts for its communicative nature. In face-to-face interaction,listeners are expected to show understanding by nodding, saying utterances such as really and uh-huh, making comments, and taking turnsparticipating in the conversation. Even in a less reciprocal situation,such as a lecture, the listener could have an opportunity to respond, forexample, by offering questions and observations. The social dimensionof listening also includes gestures, body language, and other nonverbalsignals, as well as pragmatic aspects of listening, which allow listeners to make inferences about the speaker’s intention and determineimplied meaning to respond in socially appropriate ways in a variety ofsituations (Vandergrift & Goh, 2009).The cognitive and social processes of listening are generally similar in any language. Listeners who are nonnative English speakers(NNESs), however, face a number of additional hurdles in their effortsto understand aural speech.Reflective Break Reflect on some of the ways that listening to a nonnativelanguage could be difficult.Listeners may miss part of or the entire message in their native language because they forgot what was said or could not hear very well.They also tend to tune out if a listening text is extremely long or uninteresting, or if they are distracted; however, their native knowledge ofthe language and culture helps them make sense of the input even ifthey failed to hear it in its entirety. Matters become more complicatedwhen people listen to a foreign language, especially if they do notknow it very well. Sounds blend together into a continuous stream; listeners get so caught up listening for individual words that they lose thethread of the conversation. Add to this situation the difficulty of different accents, colloquialisms, and fast-paced native speech, and listenersWhat Do Teachers Know About Listening?3

may quickly become confused. The short-lived nature of listening (asopposed to writing, where the words stay on paper) also increases thechallenge: It is impossible to preview or review the message.Reflective Break Does practice make perfect when teaching listening? Willstudents be able to understand more as they listen more?The Process View of ListeningFor a long time, listening instruction emphasized the importance ofpractice in achieving comprehension. Students were presented withtext after text in the hope that extended exposure would improvelistening comprehension with little or no analysis of how this comprehension was achieved. This method is called the product approach tolistening. The emphasis on the product of instruction assumes that thelistener receives the message and produces a single possible responseto demonstrate her understanding (Field, 2008). It means that successful comprehension is determined by correct answers to questions andfill-in-the-blank exercises. The wrong answers indicate that the listener’s comprehension failed at some point; the teacher would addressthe language and meaning mistakes but not the processes that lead tomisunderstanding, so the student may well have the same difficulty in asimilar listening situation.To better understand the nature of listening comprehension, theprocess view of listening was adopted. It highlights the fact that, ratherthan simply taking the information in and getting the meaning out, listeners process input to create meaning from the incoming sounds andtheir own knowledge of the world. The process model treats listeningas a complex interaction of cognitive, affective, and social variables toensure reception, processing, and understanding of a spoken message(Vandergrift & Goh, 2012).4Teaching Listening

Reflective Break What are your views on the importance of product andprocess in the listening classroom?Essential to successful comprehension is the listener’s backgroundknowledge and its influence on perception and memory. It is usuallydescribed in terms of the schema theory, which is based on the idea thatall the knowledge that people carry in their minds is organized intointerrelated patterns, or schemata (the plural of schema). A schema is amental image of a particular situation or event, made up from previousencounters with similar events. There are two types of schema: content,which refers to general knowledge and life experience, as well as rele vant knowledge of the subject matter, and formal, which reflects thelistener’s awareness of text types and genres. Cultural schema, whichis also sometimes mentioned, describes familiarity with socioculturalnorms of a given community.In the process of listening, people invoke different types of schemata to render the meaning of the message. For example, whenEnglish native speakers from the United States hear the word parade,they think about people lining the streets to watch floats and marching bands. This is their schema for parade, which is very different frommine. I grew up in the Soviet Union, so my mental picture of a paradealways involves military troops marching on Moscow’s Red Squareamid red flags. People all have their own personal schema shaped bytheir experiences; they understand new information by relating it tothe existing schemata and predicting what they might hear next. Theconcept of schema highlights the importance of background knowledge in listening.Reflective Break How can the knowledge of schema theory be helpful inteaching listening?What Do Teachers Know About Listening?5

Bottom-Up and Top-Down ProcessingWhen listeners listen, they make sense of the incoming informationin two different ways. Bottom-up processing refers to deriving meaning from individual lexical, grammatical, and pronunciation items. Itunderlies the decoding process, from sounds to words and grammaticalrelations between them to sentences leading to overall comprehension.Top-down processing operates with existing schemata, ideas, and content.Rather than relying on discrete segments, people let their knowledgeand expectations guide their understanding of what they hear. The twoprocesses complement each other; the choice of one over the otherdepends on the topic, content, and type of the text. An example frommy experience with audio books shows how top-down and bottom-upprocesses work together to ensure comprehension: I was enjoying DanBrown’s novel The Da Vinci Code and came across a phrase: “Langdonhas hung NE PAS DERANGER signs on hotel room doors to catchthe gist of the captain’s orders.” The bottom-up processing activatedmy minimal knowledge of French to understand the negation. Themention of hotel room doors invoked my general knowledge of hotelsand made me think about Do not disturb signs before the next phrase,“Fache and Langdon were not to be disturbed under any circumstances,” confirmed my guess.Reflective Break Read the following text or choose a lecture from http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/audio-video-courses/. As you listen or read,take note of what you do to understand the content. Do yourely on top-down or bottom-up processing? When? Whatelse do you do to get the meaning?Most spoken text differs in many ways from written text; therefore, theobject of listening is different from that of reading. A comparison of atranscribed spoken text and a written text is likely to reveal a numberof significant differences. Spoken text is fragmented (loosely structured) and involved (interactive with the listener). Written text, on theother hand, is integrated (densely structured) and detached (lacking ininteraction with the listener). These functional distinctions are realizedin certain linguistic features (Flowerdew & Miller, 2005, p. 48).6Teaching Listening

Listening to Comprehend or toAcquire the Language?When teachers ask students to make predictions, discuss the mainidea of the text, or summarize it, the primary concern is how well theyunderstand what they hear. Teachers teach students strategies to facilitate comprehension and tell them not to cling to every word but to tryto derive meaning from what they recognize. This approach encourages learners to rely on familiar language and provides little opportunity to boost linguistic development. It equates listening with listening comprehension, overlooking the important role listening playsin language acquisition. To help learners further their learning of thelanguage, teachers can supplement comprehension goals, which focuson extracting information from the text, with acquisition goals, whichdraw their attention to linguistic features of the text, so that studentsexplicitly notice them and incorporate them into their speech. Thiscan be achieved by including activities that require “accurate recognition and recall of words, syntax and expressions that occurred in theinput” such as “dictation, cloze exercises, and identifying differencesbetween spoken and written text” (Richards, 2008, p. 87). Additionally, students could perform more productive activities requiring use oftarget forms from the text, such as reading transcripts aloud, sentencecompletion, dialogue practice, and role-playing. As learners work withtranscripts and use the language in speaking activities, they masterthe forms they have heard. Extending listening instruction to developstudents’ abilities to understand oral speech and to acquire sound patterns, vocabulary, and grammar reflects the multifaceted nature of thelistening process.Reflective Break Reflect on a meaningful listening experience you havehad. What made it meaningful or useful to you in terms ofcommunication, new information, ideas, skills, languageitems, etc.? Alternatively, reflect on a lack of meaningfulexperiences and what may have been missing. How can thisunderstanding inform your teaching of listening?What Do Teachers Know About Listening?7

Listening SkillsA further insight into the nature of listening has been offered by theconcept of skills. Skills can be described as automatic cognitive processes that ensure understanding of the language (Richard & Burns,2012). As people listen, they assemble words from sounds, extract themeaning, and ignore irrelevant input without noticing these cognitiveactions. An influential classification by Richards (1983) lists 33 conversational and 18 academic listening skills covering different levelsof processing (e.g., sound, word, sentence, discourse). Here are someexamples: discriminating between the distinctive sounds of the language recognizing stress patterns of words recognizing intonation patterns to signal information structure detecting key words guessing the meaning of words from context recognizing grammatical word classes recognizing cohesive devices inferring links and connections between events processing speech at different rates identifying the topic and following its developmentSome researchers question the vague nature of a skill as well asthe value of separating listening into smaller components, but o thersbelieve that a skills-based approach is helpful in analyzing weaknessesin the listening process. According to Field (2008), a skills-basedapproach provides a checklist that allows the teacher to pinpointcomprehension problems and give learners itemized feedback clearlyindicating the areas that need more practice. Also, a skills-basedapproach sustains individual subskill practice in preparation for morecomprehensive listening activities. To help learners make discrete abilities a part of their listening behavior, isolated skills training should beintegrated with general comprehension work involving larger contextsand goals.8Teaching Listening

Reflective Break If you were asked to compile a list of specific steps you taketo get the meaning as you listen, what would it look like?What are the main reasons that affect your choice of aparticular strategy?Listening StrategiesAnother aspect of active listening is the variety of deliberate actionslisteners take to achieve a particular purpose. When people listento a lecture, they usually write down key words and concepts toretain information and review it later. Taking notes during listeningis an example of a listening strategy. Those researchers who agreethat strategies are critical in coping with listening tasks distinguishbetween cognitive, metacognitive, and socio-affective categories. Cognitive strategies, such as predicting and guessing words from context,help organize listening to complete a task, achieve comprehension, andpromote learning. Metacognitive strategies, or thinking about listening, facilitate planning, monitoring, evaluating, and reflecting on thelistening process. Asking oneself if the main idea is understood is anexample of a metacognitive strategy. Socio-affective strategies involvecommunicating with teachers, classmates, and native speakers, as wellas developing self-confidence and motivation. When students checkanswers in groups or seek additional practice opportunities, they usesocio- affective strategies. Mendelsohn (1994), Flowderdew and Miller(2005), and Vandergrift and Goh (2012) provide useful inventories oflistening strategies and describe how they can be taught in class.Reflective Break How can you raise your students’ awareness of the use oflistening strategies?Researchers continue to investigate strategies used by successful listeners and the effects of strategy training in nonnative languageWhat Do Teachers Know About Listening?9

listening. There is a general agreement on the positive effect of suchstrategies, although some of them are more difficult to describe andteach than others. Rost (2011) names the following as effective listening strategies: predicting, inferencing, monitoring comprehension,asking for clarification and responding in an interactive exchange,and evaluating one’s own listening processes. These strategies needto be discussed in class along with other actions successful listenerstake to ensure comprehension. For strategy training to be effective,it should be incorporated into listening activities so that students cansee how combining several strategies helps them gain in listening andself-confidence.Reflective Break The theory outlined in this chapter describes the productand process views of listening, the interaction of bottom-upand top-down processing of aural information, the languagecomprehension and acquisition approach to teachinglistening, and the concepts of listening skills and strategies.Discuss the implications of these issues for a group oflearners you are familiar with.10Teaching Listening

3How Can TeachersTeach Listening?The research findings discussed in the previous chapter have severalimportant implications for teachers. Although many aspects of thetraditional listening classroom remain the same as in the past, the current view of listening as a many-sided interactive process necessitatesa more comprehensive approach to teaching listening to help learnersmeet the challenge of real-life listening. Although listening is an individual activity hidden in one’s brain, the teaching and learning of howto listen could be taken out of students’ private domain into the publicspace of the classroom. The focus of instruction changes from whethercomprehension is achieved to how it is achieved.Reflective Break How was foreign language listening taught in yourexperience?The Diagnostic ApproachTypically, teachers do some prelistening and then have students listento the text and perform a variety of tasks. Teachers evaluate students’comprehension based on the correctness of their responses and proceed to the next activity. Implicit here is the focus on the result, theproduct of listening in the form of correct answers. This approach testsstudents’ listening comprehension, informing them that they failedat certain points, but does little to teach how to listen, that is, to help11

them understand what went wrong with their listening and how itcould be repaired. Field (2008) calls for a diagnostic approach to listening, which allows teachers and students to attend to listening difficulties and practice strategies to diminish them. Characteristics of theapproach are described in the following sections.Using Incorrect Answers to Detect Weaknesses,and Designing Activities to HelpHow often do teachers rush to supply a “correct” answer when a student fails to respond to a listening task? Teachers may play a recordingseveral times and ask for other students’ input to make things right,missing an opportunity to determine the reason for the listening error.To revise this approach, a teacher could identify problems by making anote of students’ lapses in comprehension as she checks their answers.She would then discuss with students how they arrived at a certainanswer, what prevented them from understanding parts of the text, andwhat could be done to improve their listening facilities. Finally, shewould follow up with activities that target specific listening problemsthat emerged during the discussion. The aim is to increase students’awareness of their listening processes and reinforce effective listeningbehaviors they can use when they face these problems again.Reflective Break How can teachers best determine whether their studentsunderstand the listening material they give them?Avoiding Listening Tasks That Require MemorizationUnderstanding a message does not mean remembering every singledetail, so students’ inability to recall information does not always signala lack of comprehension. Yet some exercises—namely, multiple-choiceand very specific questions—test listeners’ memory skills rather thanfocusing on the listening process. Instructors should try to include various types of comprehension questions that discuss the content of thetext as well as invite students to examine their listening performance.12Teaching Listening

Helping Students Develop a Wider Rangeof Listening StrategiesIneffective listeners rely on a single strategy (e.g., focusing on individual sentences, missing the relationship between ideas) without changing or adapting it. To cope with difficult texts more effectively, studentsshould be exposed to a variety of strategies. Explaining, modeling, andregularly practicing with students how to set goals, plan tasks, selfmonitor, and evaluate helps them control their listening. Anticipatingcontent, inferring, guessing, and recognizing redundancies improvesspecific listening problems. Encouraging interaction with classmatesand native speakers through listening expands communicative contextsand enhances self-confidence.Effective strategy use does not happen by itself. Although the veryidea of strategies may seem to be too abstract to students, teachers canhelp them appreciate the importance of strategies by including activities with a focus on their listening process. For example, students coulddiscuss (in small groups or with the class) what they did to preparefor listening, follow the text, identify key points, and so forth. Or theclass could share personal experiences with various listening tasks anddevelop a master list of effective strategies for different types of texts,adding to it as their strategic competence grows. To introduce a strategy, the teacher needs to get students to realize that there is a problemand a way of dealing with it. She could model the strategy by explaining what she does and why it is helpful in this particular case, and provide multiple opportunities to practice in different listening situations.Depending on the task, she also could remind students to be flexible intheir choice of strategies and to employ strategic listening outside ofthe class.Reflective Break Make a list of listening strategies you are familiar with. Arethere any strategies that seem more important than others?Why?How Can Teachers Teach Listening?13

Differentiating Between Listening SkillsBy identifying a set of distinctive behaviors that work together towardcomprehension, teachers allow learners yet another glimpse into thelistening process. Listeners may be used to employing microskills intheir native language, but specific activities need to be designed tohelp them transfer those skills into a new language. Although each skillcould be practiced separately, the key to skills instruction is not to treatthem as a laundry list of discrete practice points that students get or donot get. Rather, skill training should become a part of a larger listeningproficiency picture, inviting students to try new behaviors in a varietyof contexts and tasks.Reflective Break What is the difference between strategies and skills? Howcan this awareness help in listening instruction?Providing Top-Down and Bottom-Up Listening PracticeThe fact that listening is a complex multistep procedure that involvesdifferent types of processing implies that both top-down and bottom-upskills should be practiced in the classroom. Although many teacherstend to favor such top-down activities as comprehension questions,predicting, and listing, listening practice should incorporate bottom-upexercises for pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary that allow learners to pay close attention to language as well.Bottom-up processing helps students recognize lexical and pronunciation features to understand the text. Because of their direct focus onlanguage forms at the word and sentence levels, bottom-up exercisesare particularly beneficial for lower level students who need to expandtheir language repertoire. As they become more aware of linguistic features of the input, the speed and accuracy of perceiving and processingaural input will increase. To develop bottom-up processing, studentscould be asked to distinguish individual sounds, word boundaries, and stressedsyllables identify thought groups14Teaching Listening

listen for intonation patterns in utterances identify grammatical forms and functions recognize contractions and connected speech recognize linking wordsTop-down processing relies on prior knowledge and experience tobuild the meaning of a listening text using the infor

practice approach to English language teaching, and each book offers a wide variety of practical teaching approaches and methods for the topic at hand. Each book also offers opportunities for reflections that allow teachers to interact with the materials presented. The books can be use