Transcription

THANKSFOR DOWNLOADING THIS EBOOK!We have SO many more booksfor kids in the in-beTWEEN agethat we’d love to share with you!Sign up for our IN THEMIDDLE books newsletter andyou’ll receive news about othergreat books, exclusive excerpts,games, author interviews, andmore!

CLICK HERE TOSIGN UPor visit us online to sign up ateBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com/midd

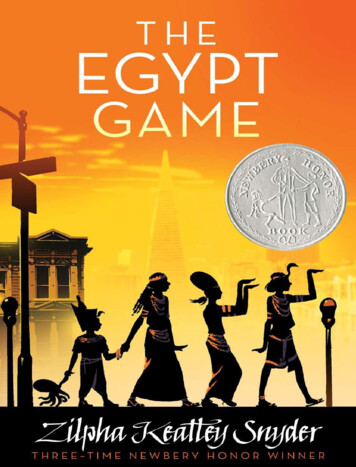

ContentsTHE DISCOVERY OF EGYPTENTER APRILENTER MELANIE—AND MARSHALLTHE EGYPT GIRLSTHE EVIL GOD AND THE SECRET SPYEYELASHES AND CEREMONYNEFERBETHPRISONERS OF FEARSUMMONED BY THE MIGHTY ONESTHE RETURN TO EGYPT

EGYPT INVADEDELIZABETHAN DIPLOMACYMOODS AND MAYBESHIEROGLYPHICSTHE CEREMONY FOR THE DEADTHE ORACLE OF THOTHTHE ORACLE SPEAKSWHERE IS SECURITY?CONFESSION AND CONFUSIONFEAR STRIKESTHE HEROGAINS AND LOSSESCHRISTMAS KEYSWilliam S. and the Great Escape

ExcerptAbout Zilpha Keatley Snyder

To the boys and girls I knew atWashington School and toSusan and Tammy for the loanof some secrets

INTRODUCTION BY THEAUTHOROver the years since The Egypt Gamewas first published, I’ve heard from agreat many readers. Their letters havebeen wonderful, telling me how muchthey enjoyed the book and how theymade up their own versions of the game,and almost always asking me thefollowing question: “Where do you getyour ideas?”That question is perhaps the onefiction writers hear more frequently thanany other. But it’s the wrong question. Abetter one would be “How do you get

your ideas?” Because getting story ideasis pretty much a matter of habit—thehabit of taking interesting, but ratherordinary, bits and pieces of reality andbuilding on them, weaving them togetheruntil a story emerges. Ideas can comefrom anywhere. Everyone has goodsources of ideas. But the building andweaving part can be hard—fun andexciting but also difficult anddemanding.I’ve often used The Egypt Game toillustrate how any story can have “idearoots” that go back to different periodsin one’s life. The longest root goes backto when I was in fifth grade and becamefascinated by the culture of ancientEgypt. I read everything I could find on

the subject, made up my ownhieroglyphic alphabet, and played myown rather simple, and very private,Egypt Game, which included walking toschool like an Egyptian—imaginingmyself as Queen Nefertiti, actually.A somewhat shorter root goes back towhen I was teaching in Berkeley,California, while my husband was ingraduate school. My classes usuallyconsisted of American kids of all races,as well as a few whose parents weregraduate students from other countries.All six of the main characters in TheEgypt Game are based, loosely but withethnic accuracy, on people who were inmy class one year—even Marshall,whom I had to imagine backward in time

to four years of age.And the shortest root goes back towhen my own daughter, a sixth-grader atthe time, became intrigued by my storiesabout my “Egyptian period” and startedher own version of the Egypt Game. Hergame was much more complicated thanmine and involved many of the activitiesI described in the story, including themummification of our parakeet, who,like Elizabeth’s Prince Pete-ho-tep, diedby feline assassination. A few yearslater, when my daughter was in herteens, she sometimes threatened to gothrough every one of my books lookingfor all the good ideas she had given me—and charge me for them!But as I said before, all these idea

roots came from rather ordinary sourcesthat needed to be built on and woventogether until they became the story ofThe Egypt Game.Zilpha Keatley Snyder

The Discovery ofEgyptNOTLONG AGO IN A LARGE UNIVERSITYCalifornia, on a street calledOrchard Avenue, a strange old man ran adusty shabby store. Above the dirtyshow windows a faded peeling signsaid:TOWN INA-ZANTIQUESCURIOSUSED MERCHANDISE

Nobody knew for sure what the A-Zmeant. Perhaps it referred to the fact thatall sorts of strange things—everythingfrom A to Z—were sold in the store. Orperhaps it had something to do with theowner’s name. However, no one seemedto know for sure what his name actuallywas. It was all part of a mysteriousuncertainty about even the smallest itemof public information about the old man.Nobody seemed certain, for instance,just why he was known as the Professor.The neighborhood surrounding theProfessor’s store was made up ofinexpensive apartment houses, littlefamily-owned shops, and small, aginghomes. The people of the area, many ofwhom had some connection with the

university, could trace their ancestors toevery continent, and just about everycountry in the world.There were dozens of children in theneighborhood; boys and girls of everysize and style and color, some of whomcould speak more than one languagewhen they wanted to. But in theirschools and on the streets they allseemed to speak the same language andto have a number of things in common.And one of the things they had incommon, at that time, was a vague andmysterious fear of the old man called theProfessor.Just what was so dangerous about theProfessor was uncertain, like everythingelse about him, but his appearance

undoubtedly had something to do withthe rumors. He was tall and bent and histhin beard straggled up his cheeks likedry moss on gray rocks. His eyes weredark and expressionless, and set so deepunder heavy brows that from a distancethey looked like dark empty holes. Andfrom a distance was the only way thatmost of the children of Orchard Avenuecared to see them. The Professor livedsomewhere at the back of his dingystore, and when he came out to stand inthe sun in his doorway, smaller childrenwould cross the street if they had towalk by.Now and then, older and braver boys,inspired by the old man’s strangeness,would dare each other into an attempt to

tease or torment him—but not for long.Their absolute failure to get any sort of areaction from their victim was not onlydiscouraging, it was weird enough tospoil the fun for even the bravest ofbullies.Since there were several antiquestores in the area to draw the buyers, theProfessor seemed to do a fairly goodbusiness with out-of-town collectors; buthis local trade was very small. It wassaid that he sold items that were used,but not antique, very cheaply, but evenfor grown-ups the prospect of a bargainwas often not enough to offset thediscomfort of the old man’s stony stare.It was one day early in a recentSeptember that the Professor happened

to be the only witness to the verybeginning of the Egypt Game. He hadbeen looking for something in a seldomused storeroom at the back of his shop,when a slight noise drew him to awindow. He lifted a gunnysack curtain,rubbed a peephole in the thick coating ofdirt, and peered through. Outside thatparticular window was a small storageyard surrounded by a high board fence. Ithad been years since the Professor hadmade any use of the area, and the weedgrown yard and open lean-to shed wereempty except for a few pieces offorgotten junk. But as the old man peeredthrough his dirty window, two girls werepulling a much smaller boy through ahole in the fence.

The Professor had seen both of thegirls before. They were about the sameage and size, perhaps eleven or twelveyears old. The one who was tugging atthe little boy’s leg was thin and palelyblond, and her hair was arranged in astraggly pile on the top of her head. Herhigh cheekbones and short nose werefaintly spattered with freckles and therewas a strange droopy look to her eyes.The old man recalled that she had beenin his store not long before, and alongwith some other improbable informationshe had disclosed that her name wasApril.The other girl, who had the little boyby the shoulders, was African American,as was the little boy himself. A

similarity in their pert features andslender arching eyebrows indicated thatthey were probably brother and sister.The Professor had seen them pass hisstore many times and knew that theywere residents of the neighborhood.The fence that surrounded the storageyard was high and strong and topped bystrands of barbed wire, but one thinplank had come loose so that it waspossible to swing it to one side. Both thegirls were very slender and they hadapparently squeezed through withoutmuch trouble, but the boy was causing aproblem. He was only about four yearsold but he was sturdily built; moreover,he was clutching a large stuffed toy tohis chest with both arms. He paid not the

slightest attention to the demands of thetwo girls that he, “Turn loose of thatthing for just a minute, can’t you?” and,“Let me hold Security for you just tillyou get through, Marshall.” Marshallremained very calm and patient, but hisgrip on his toy didn’t relax for a second.When the little boy and his huge plushoctopus at last popped free into the yard,the girls turned to inspect theirdiscovery. Their eyes flew over thebroken birdbath, the crumbling statue ofDiana the Huntress, and the stack offancy wooden porch pillars, and came torest on something in the lean-to shack. Itwas a cracked and chipped plasterreproduction of the famous bust ofNefertiti. The two girls stared at it for a

long breathless moment and then theyturned and looked at each other. Theydidn’t say a word, but with wideningeyes and small taut smiles they sent acharge of excitement dancing betweenthem like a crackle of electricity.The customer, an antique dealer fromSan Francisco, was stirring restlessly inthe main room of the store. Hearing him,the Professor was reminded of hiserrand. He replaced the sacking curtainand left the storeroom. It was more thanan hour later that he remembered thechildren and returned to the peephole inthe dirty window.There had been some changes madein the storage yard. Some of the ornateold porch pillars had been propped up

around the lean-to so that they seemed tobe supporting its sagging tin roof; thestatue of Diana had been moved intoposition near this improvised temple;and in the place of honor at the back andcenter of the shed, the bust of Nefertitiwas enthroned in the broken birdbath.The little boy was playing quietly withhis octopus on the floor of the shed andthe two girls were busily pulling the talldry weeds that choked the yard, andstacking them in a pile near the fence.“Look, Melanie,” the girl namedApril said. She displayed a pricklybouquet of thistle blossoms.“Neat!”Melanienoddedenthusiastically. “Lotus blossoms?”April considered her uninviting

bouquet with new appreciation. “Yeah,”she agreed. “Lotus blossoms.”Melanie had another inspiration. Shestood up, dumping her lap full of weeds,and reached for the blossoms—gingerlybecause of the prickles. Holding them atarm’slength,sheannounceddramatically, “The Sacred Flower ofEgypt.” Then she paced with dignity tothe birdbath and with a curtsy presentedthem to Nefertiti.April had followed, watchingapprovingly, but now she suddenlyobjected. “No! Like this,” she said.Taking the thistle flowers, shedropped to her knees and bent lowbefore the birdbath. Then she crawledbackward out of the lean-to. “Neat,”

Melanie said, and, taking the flowersback, she repeated the ritual, addinganother refinement by tapping herforehead to the floor three times. Aprilgave her stamp of approval to this latestinnovation by trying it out herself, doingthe forehead taps very slowly anddramatically. Then the two girls wentback to their weed pulling, leaving thethistles before the altar of Nefertiti.A few moments later the blond girlsat back suddenly on her heels andclapped a hand to her right eye. Whenshe took it away the Professor, peeringthrough his spy hole, noticed that the eyehad lost its strange droopy appearance.“Melanie,” April said. “They’re gone.I’ve lost my eyelashes.”

At about that point, a customer,entering the Professor’s store, forcedhim to leave his vantage point at thedirty window. So he missed the franticsearch that followed. He also missed theindignant scolding when the girlsdiscovered that April’s false eye lasheshad fallen before the altar of Nefertiti,where Marshall had found them andquietly beautified one of the button eyesof his octopus.When the Professor finally was freeto return to his peephole the children hadgone home, leaving the storage yardalmost free from weeds, and a thistleblossom offering before the birdbath.

Enter AprilHERAPRIL HALL, BUT SHEOFTEN CALLED herself April Dawn.Exactly one month before the EgyptGame began in the Professor’s backyardshe had come, very reluctantly, to live inthe shabby splendor of an oldCalifornia-Spanish apartment housecalled the Casa Rosada. She camebecause she had been sent away byDorothea, her beautiful and glamorousmother, to live with a grandmother shehardly knew, and who wore her grayhair in a bun on the back of her head.NAME WAS

None of April and Dorothea’sHollywood friends ever had gray hair,except the kind you have on purpose, nomatter how old they got otherwise.It had been on that very first day,early in August, that April and theProfessor first met. On that first morningof her new life April had spent half anhour arranging her limp blond hair in ahigh upsweep, such as Dorotheasometimes wore. It was hard work,much harder than it looked whenDorothea did it. As she pinned andrepinned, April told herself withrighteous bitterness that Caroline wassure to make her take it all down againanyway, and all her hard work would befor nothing.

But if her grandmother noticed thehairdo, she said nothing about it at thebreakfast table. She didn’t even seem tonotice how quiet and depressed Aprilwas and try to cheer her up withquestions and conversation. Aprildecided that Caroline must be theuninterested kind of person who didn’tnotice much of anything. Well, that wasgood. Because, for the short while shewas here, April intended to go right onleading the kind of life she was used to,and if Caroline didn’t even notice—well, at least there wouldn’t be anytrouble. All through breakfast Carolinewent on saying almost nothing, butfinally when she was almost through shedid say that she wouldn’t mind being

called Grandma or even Grannie, ifApril liked.“Oh, I guess I’ll just go on calling youCaroline,” April said. And then withpointed sweetness she added, “That is,unless you’d rather I didn’t.” Dorotheaalways called her Caroline instead ofMother, so what was wrong withCaroline instead of Grandmother? Ofcourse, Caroline wasn’t Dorothea’smother. She was the mother of April’sfather, who had died in an accidentbefore April even had a chance to get toknow him.Nothing more was said until Carolinebegan to clear the table. Then she said,“I’ve arranged for you to have lunchwith Mrs. Ross and her children on the

second floor. She said she’d sendMelanie, her little girl, up for you abouttwelve o’clock. The rest of the timeyou’ll be more or less on your own, butI’d appreciate it if you’d let Mrs. Rossknow if you leave the building. Just tellher where you’re going and how soonyou’ll be back.”“I could get my own lunch,” Aprilsaid. “I cooked a lot at home.”“I know,” Caroline said, “but I’vemade this arrangement with Mrs. Ross,so we’ll try it for a while, just till schoolstarts. The Rosses are very nice people.Mrs. Ross teaches school and herhusband is a graduate student at theuniversity. Their little girl is about yourage, and they have a boy about four.

They’re African Americans,” she added.April shrugged. “Dorothea and Iknow a lot of black people. There are alot of black people in show business.”Caroline smiled. “I see,” she said.“Tell me, April, what do you think of theCasa Rosada?”“The what?” April said.“The Casa Rosada, this apartmenthouse.”“Oh.” April repeated her shrug. “It’sokay.” Actually it had been a pleasantsurprise—that is, it would have been ifshe’d been in the mood for pleasantsurprises. The last time she’d visitedCaroline, she’d lived in a tinysupermodern apartment, like a cell, onlywith paintings. The Casa Rosada was

very different. Somehow it made Aprilthink of Hollywood and home. It wasvery Spanishy-looking with great thickwalls, arched doorways, fancy irongrillwork, stained-glass panels in thewindows and tile floors in the lobby.Outside it was painted pink.Caroline smiled her small primsmile. “Mr. Ross calls it the PetrifiedBirthday Cake, and I’m afraid that’s apretty good description. It must havebeen quite the thing when it was builtback in the twenties. Of course, it’sterribly run down now, but theapartments are roomy. It’s so hard to finda modern place with two bedroomsthat’s not awfully expensive.”It hadn’t occurred to April that

Caroline had moved because of her—soshe could have a bedroom of her own.She knew she ought to feel grateful, butfor some reason what she really felt wasangry. What made Caroline think thatApril was going to be with her longenough for it to make any differencewhether she had a room of her own ornot? Dorothea had promised it wouldonly be for a little while. Only untilthings got more settled down and shewasn’t on tour so much of the time.Before Caroline left she wrote downthe phone number of the library at theuniversity, where she worked, in casethere was an emergency and Aprilneeded her. There wasn’t muchlikelihood of that. April was used to

taking care of herself.When she was alone April went outon the tiny iron balcony and lookedaround. Caroline’s apartment was on thethird and top floor and fronted on theavenue. Most of the buildings in theneighborhood were only one or twostories high, so from where she stoodshe could get a pretty good idea of thelay of the land. On one side of the CasaRosada were some small shops—aflorist, a doughnut shop and some others.On the other, across a narrow alley, wasa tall billboard that pretty much blockedthe view, but by leaning forward Aprilcould see the façade of a long lowbuilding. She could tell that it was verydingy and the windows were badly in

need of washing. From her position—high and to one side—she couldn’t makeout the sign; but from the interestingclutter in the show windows it seemed tobe some sort of secondhand store.A store of that type always offered aninteresting possibility for exploring, butApril was really looking for somethingelse at the moment. A drugstore might door perhaps a beauty shop. WhenDorothea and Nick, Dorothea’s agentand good friend, had put April on the busthe morning before, they had eachslipped her some money. It added up toquite a bit more than April was used tohaving all at once, and she wanted tomake some purchases before Carolinefound out about it. Not that she really

thought that Caroline would take themoney away, but it would be just like agrandmother to insist that it be spent onsomething “sensible” like new shoes ora school dress.A few minutes later April was takingthe old-fashioned elevator, with its doorlike a folding iron fence, down to thelobby. It wasn’t until she was out on thesidewalk that she remembered whatCaroline had said about reporting toMrs. Ross before she left the building.She paused long enough to decide thatreporting wouldn’t be possible until thatafternoon. After all, Caroline hadn’teven told her where the Rosses lived, atleast not exactly. With that settled to hersatisfaction she went on up the street.

The girl in the drugstore lookedsurprised, but she didn’t make too muchof a big deal out of April’s purchases.When she got out the false eyelashes, shedid ask if they were to be a present forsomeone. But when April made hersmile poisonously sweet and said, “Ohno,” she seemed to get the point andstopped asking questions. On the wayhome April decided that since there wasstill plenty of time before twelveo’clock, she might as well explore thestore she had seen from the balcony.The store was called A–Z, and itsdusty show windows were crammedwith a weird clutter of old and exoticlooking objects—huge bronze orientalvases next to some beat-up old pots and

pans. An old-fashioned crank telephone,a primitive-looking wooden mask and atreadle sewing machine. Two kerosenelamps and a huge broad-bladed knifewith a carved ivory handle. April felt atiny tingle of excitement. She always feltthat way about old stuff. It had been oneof the few things that she and Dorotheadidn’t agree on. Dorothea always said,“I’ll take mine new and shiny.”It was dusky inside the store after theoutdoor brightness. There didn’t seem tobe any clerks at all. Not that it mattered,because April was only looking. Shesquatted down in front of a glass casefull of small objects: vases and jars,some partly cracked or broken, crudelymade jewelry and tiny statues. All of it

looked terribly ancient and interesting.She was pressing her nose to the glasswhen suddenly she knew she was beingwatched.An old man was leaning over thecounter right above her head. “Ohhello,” April said and went on looking ata tiny statue with broad shoulders, shortlegs and a hole in the top of its head. Itlooked almost Egyptian and April hadalways been especially interested inEgyptian stuff. After a moment shelooked up again and the man was stillthere. “What’s that?” she asked, pointingto the tiny figure.

“That is a pre-Columbian burialfigure. It was made in Mexico about twothousand years ago.” The old man’svoice was slow and rusty.April looked up again quickly. “Twothousand—you’re kidding,” she said.But on second glance she was sure he

wasn’t. He wasn’t kidding and he wasn’tquite like anyone she’d ever seen before.He had a strange skimpy-looking littlebeard and his eyes were deep set and asblank as an empty well. He said nothingmore, and not by so much as a flickerdid his face reveal what he was thinking.April was impressed. A deadpan wassomething she’d cultivated herself, andshe knew from experience that such aperfect one was not easily come by. “Imean,” she said with respectful caution,“is it really that old?”The old man only tilted his stone facedownward in a stiff nod. April wentback to studying the objects in the case,but now her interest was divided. Theold man was almost as unusual as the

strange things behind the dusty glass. In afew moments she stood up and smiled athim. It was a real smile, small andquick, not the gooey kind she usuallyused on grown-ups. Somehow she had anotion he wouldn’t fool easily.“My name is April Hall,” she said.“I’ve just come to live in the apartmenthouse next door, with my grandmother. Iused to live in Hollywood with mymother.” She paused. For a moment itlooked as if the old man wasn’t going toanswer at all, but at last his craggy facecracked enough to allow the escape oftwo small words, “I see.”April regarded him with grudgingadmiration. It usually wasn’t very hardto pick the real meaning out of things

people said, if you watched themclosely. But this one wasn’t going to beeasy. The “I see” said nothing at all. Itwasn’t friendly, or angry, or curious, oreven bored. In fact, there was somethingabout the absolute nothingness behind itthat was a little bit frightening, likeputting out your hand to touch somethingthat wasn’t really there. April began tochatter a little nervously. “I’m a nutabout things like that.” She motionedtowards the case. “I’m always readingabout ancient times and stuff like that.You know, Babylonia and Egypt andGreece and China. It’s kind of a hobbyof mine. As a matter of fact, I’m evenplanning to be an archaeologist when Igrow up. Some people think that’s a

pretty kooky ambition for a girl—but Ilike it. You see, I have this theory abouthow I was a high priestess once, in anearlier reincarnation. Do you think that’spossible?”“Possible?” The old man’s voicequavered the word into a whole flock ofsyllables. “Many things are possible.”“That’s what I think, too. A lot ofpeople don’t think so, though. When Itold Nick—he’s my mother’s agent—about the high priestess thing he justlaughed. He said, ‘I don’t know aboutthose other reincarnations, kiddo, but inthis one you’re a nut.’ ”Before the old man could answer, ifhe was going to, a couple of ladiesbreezed in the doorway. Of course, they

interrupted right away when they sawthat April was just a kid.As she drifted out the door and backto the Casa Rosada, April wonderedwhy she’d gabbed so much. It wasn’treally like her. She’d started out justtrying to get the old man to talk and thensomehow she couldn’t quit. It wasalmost as if the old man’s deadly silencewas a dangerous dark hole that had to befilled up quickly with lots of words.

Enter Melanie—andMarshallON THAT SAME DAY IN AUGUST, JUST A FEWMINUTES before twelve, Melanie Rossarrived at the door of Mrs. Hall’sapartment on the third floor. Melaniewas eleven years old and she had livedin the Casa Rosada since she was onlyseven. During that time she’d welcomeda lot of new people to the apartmenthouse. Apartment dwellers, particularlynear a university, are apt to come and go.Melanie always looked forward to

meeting new tenants, and today wasgoing to be especially interesting. Today,Melanie had been sent up to get Mrs.Hall’s granddaughter to come down andhave lunch with the Rosses. Melaniedidn’t know much about the new girlexcept that her name was April and thatshe had come from Hollywood to livewith Mrs. Hall, who was hergrandmother.It would be neat if she turned out tobe a real friend. There hadn’t been anygirls the right age in the Casa Rosadalately. To have a handy friend again, forspur-of-the-moment visiting, would begreat. However, she had overheardsomething that didn’t sound toopromising. Just the other day she’d heard

Mrs. Hall telling Mom that April was astrange little thing because she’d beenbrought up all over everywhere andnever had much of a chance to associatewith other children. You wouldn’t knowwhat to expect of someone like that. Butthen, you never knew what to expect ofany new kid, not really. So Melanieknocked hopefully at the door ofapartment 312.Meeting people had always been easyfor Melanie. Most people she liked rightaway, and they usually seemed to feelthe same way about her. But when thedoor to 312 opened that morning, for justa moment she was almost speechless.Surprise can do that to a person, and atfirst glance April really was a surprise.

Her hair was stacked up in a pile thatseemed to be more pins than hair, andthe whole thing teetered forward overher thin pale face. She was wearing abig, yellowish-white fur thing around hershoulders, and carrying a plastic pursealmost as big as a suitcase. But most ofall it was the eyelashes. They wereblack and bushy looking, and the ones onher left eye were higher up and sloped ina different direction. Melanie’s mouthopened and closed a few times beforeanything came out.April adjusted Dorothea’s old furstole, patted up some sliding strands ofhair and waited—warily. She didn’texpect this Melanie to like her—kidshardly ever did—but she did intend to

make a very definite impression; and shecould see that she’d done that all right.“Hi,” Melanie managed after that firstspeechless moment. “I’m Melanie Ross.You’re supposed to have lunch with us, Ithink. Aren’t you April Hall?”“April Dawn,” April corrected withan offhand sort of smile. “I wasexpecting you. My grandmother informedme that—uh, she said you’d be up.”It occurred to Melanie that maybekids dressed differently in Hollywood.As they started down the hall she asked,“Are you going to stay with yourgrandmother for very long?”“Oh no,” April said. “Just till mymother finishes this tour she’s on. Thenshe’ll send for me to come home.”

“Tour?”“Yes, you see my mother is DorotheaDawn—” she paused and Melanieracked her brain. She could tell she wassupposed to know who Dorothea Dawnwas. “Well, I guess you haven’thappened to hear of her way up here, butshe’s a singer and in the movies, andstuff like that. But right now she’ssinging with this band that travels aroundto different places.”

“Neat!” Melanie said. “You meanyour mother’s in the movies?”But just then they arrived at theRosses’ apartment. Marshall met them atthe door, dragging Security by one of hiseight legs.“That’s my brother, Marshall,”Melanie said.“Hi, Marshall,” April said. “Hey,what’s that following you, kid?”Melanie grinned. “That’s Security.Marshall takes him everywhere. So mydad named him Security. You know. Likesome little kids have a blanket.”“Security’s an octopus,” Marshallsaid very clearly. He didn’t talk verymuch, but when he did he always saidexactly what he wanted to without any

trouble. He never had fooled aroundwith baby talk.Melanie’s mother was in the kitchenputting hot dog sandwiches and fruitsalad on the table. When Melanieintroduced April she could tell that hermother was surprised by the eyelashesand hairdo and everything. She probablydidn’t realize that kids dressed a littledifferently in Hollywood.“April’s mother is a movie star,”Melanie explained.Melanie’s mother smiled. “Is thatright, April?” she asked.April looked at Melanie’s mothercarefully through narrowed eyes. Mrs.Ross looked sharp and neat, with asmart-looking very short hairdo like a

soft black cap, and high wingingeyebrows, like Melanie’s. But her smilewas a little different. April was good atfiguring out what adults meant by thethings they didn’t quite say—and Mrs.Ross’s smile meant that she wasn’t goingto be easy to snow.“Well,” April admitted, “not a star,really. She’s mostly a vocalist. So farshe’s only been an extra in the movies.But she almost had a supporting roleonce, and Nick, that’s her agent, says hehas a big part almost all lined up.”“Wow, that’s cool!” Melanie said.“We’ve never known anyone beforewhose mother was an extra in themovies, have we, Mom?”“Not a soul,” Mrs. Ross said, still

smiling.During lunch, April talked a lot aboutHollywood, and the movie stars she’dmet and the big parties her mother gaveand things like that. She knew she wasoverdoing it a bit but something madeher keep on. Mrs. Ross went right onsmiling in that knowing way, andMelanie went right on being so eagerand encouraging that April thought shemust be kidding. She wasn’t sure,though. You never could tell with kids—

Egypt Game, which included walking to school like an Egyptian—imagining myself as Queen Nefertiti, actually. A somewhat shorter root goes back to when I was teaching in Berkeley, California, while my husband was in graduate school. My classes usually consisted of American kids of all races, as well as a few whose parents were