Transcription

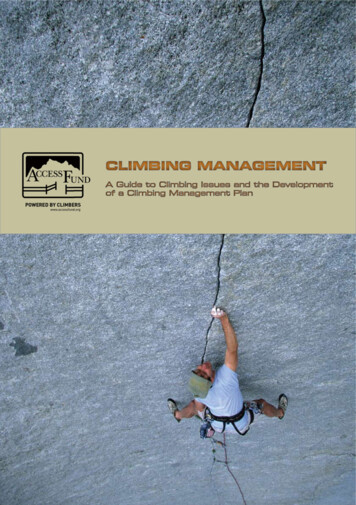

CLIMBING MANAGEMENTA Guide to Climbing Issues and the Developmentof a Climbing Management Plan

The Access FundPO Box 17010Boulder, CO 80308Tel: (303) 545-6772Fax: (303) 545-6774E-mail: info@accessfund.orgWebsite: www.accessfund.orgThe Access Fund is the only national advocacy organization whose mission keeps climbing areas open and conservesthe climbing environment. A 501(c)3 non-profit supporting and representing over 1.6 million climbers nationwide in allforms of climbing—rock climbing, ice climbing, mountaineering, and bouldering—the Access Fund is the largest USclimbing organization with over 15,000 members and affiliates.The Access Fund promotes the responsible use and sound management of climbing resources by working incooperation with climbers, other recreational users, public land managers and private land owners. We encouragean ethic of personal responsibility, self-regulation, strong conservation values, and minimum impact practices amongclimbers.Working toward a future in which climbing and access to climbing resources are viewed as legitimate, valued,and positive uses of the land, the Access Fund advocates to federal, state, and local legislators concerning publiclands legislation; works closely with federal and state land managers and other interest groups in planning andimplementing public lands management and policy; provides funding for conservation and resource managementprojects; develops, produces, and distributes climber education materials and programs; and assists in theacquisition and management of climbing resources.FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE ACCESS FUND:Visit http://www.accessfund.org.Copies of this publication are available from the Access Fund and will also be posted on the Access Fund website:http://www.accessfund.org.CLIMBING MANAGEMENT:A Guide to Climbing Issues and the Production of a Climbing Management Plan. Compiled by Aram Attarian, Ph.D.and Jason Keith, Access Fund Policy Director.CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN The Access FundACKNOWLEDGMENTS:For assistance with this publication, special thanks go to: Access Fund staff; Mark Eller and Jeff Achey, Editor; TheAmerican Alpine Club; Steve Dieckhoff, Illustrator; Timothy Duck, Wildlife Biologist, Bureau of Land Management,UT; Leave No Trace, Inc., CO; The National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS); Claudia Nissley, Cultural ResourceSpecialist, CO; Outdoor Industry Association; Jane Rodgers, Vegetation Specialist, Joshua Tree National Park, CA;and Wildlife Conservation Society, NY.COVER PHOTOGRAPHY: 2008 Jim ThornburgLAYOUT AND DESIGN: 2008 The Access FundLIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONTROL NUMBER: 2001130563››1

CMP Executive SummaryClimbing, once an obscure activity with few participants, has become a mainstream form of outdoor recreation.Climbing occurs in unique environmental settings such as cliff sides, canyons, and alpine areas, which can alsoharbor valuable natural and cultural resources. These unique settings also present land managers with distinctivechallenges. Climbing activities take place primarily off-trail, away from developed facilities, and historically havehad little oversight by land managers or owners. Given the ever-growing popularity of climbing and other outdoorrecreation activities, potential impacts on resource values must be considered and appropriate managementactions taken. This need to develop climbing management strategies has led the Access Fund to offer the climbingmanagement guidelines presented herein. This document outlines successful climbing management practices thatprovide for climbing access while protecting resource values. The following chapters address both fundamentalaspects and narrowly-focused issues pertaining to climbing management.Chapters 1 provides a schematic assessment of a typical climbing area that may prove helpful in examining theeffects of climbing activity on resource values. This illustration is applied to the section on impacts to vegetation.Chapter 2 presents information on various climbing management issues related to natural resources. Eachtopic is discussed by identifying primary issues, citing relevant literature and research, and providing examplesof Management Practices that Work. These practices are well-defined methods and management techniquesdeveloped and successfully implemented by various resource management agencies and climber organizationsacross the nation to help address climbing management concerns.Chapter 3 includes a presentation on Cultural Resources and Climbing Activity with an emphasis on issuesrelating to Native American sacred sites, archeological and historic sites, pictographs and petroglyphs, and issuespertinent to the National Historic Preservation Act. A schematic assessment of a climbing area is presented in thissection in relation to cultural resources. Chapter 4, Social Impacts and Climbing, addresses visual impacts andother considerations such as pets, noise, and litter. Chapter 5 analyzes Activities and Areas of Special Concernto provide information and awareness on a growing number of climbing activities such as bouldering, ice climbing,dry tooling, and alpine climbing. This chapter also discusses unique and sometimes controversial climbingenvironments like wilderness and caves, and presents a short summary on climbing and economic considerations.CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN The Access FundChapter 6 outlines Climbing Management Methods and discusses specific Philosophies and Tools used by landmanagers to respond to specific climbing issues such as visitor capacity, recent increases in climber visitation,and the development of new climbing routes. Chapter 7 provides a template for the Production of a ClimbingManagement Plan. Emphasis in this chapter is placed on developing clearly stated goals and objectives, definingthe scope and longevity of the CMP, and conducting a thorough review of climbing activity by including members ofthe relevant user group. An outline for a successful CMP is also suggested.››2

CMP Table of ContentsCLIMBING MANAGEMENT:A Guide to Climbing Management and the Production of a Climbing Management PlanFORWARD: Introduction and the Purpose and Need of a Climbing Management Plan 1Chapter 1. Assessment of a Climbing Area 7Chapter 2. Climbing and Natural Resources 8Ecological Impacts 8Climber Trails 9Bivouac and Backcountry Camping 10Human Waste 11Vegetation 13Water Resources 16Wildlife 17Chapter 3. Cultural Resources and Climbing Activity 21Assessment of Impacts to Cultural Resources 22CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN Table of ContentsChapter 4. Social Impacts and Climbing 24Visual or Aesthetic Impacts 25Fixed Safety Anchors 27Placement of Bolts as a Resource Protection Tool 27Liability and Fixed Anchors 28Pets 30Noise 31Litter 31Guide Services and Organized Climbing Groups 32Parking and Transportation 34User Fees 35Safety and Risk Management 35Liability 35Search And Rescue 36Economic Considerations 37Chapter 5. Activities and Areas of Special Concern 38Bouldering 39Ice Climbing 42Alpine Areas 43Designated Wilderness 44Wilderness and Solitude 45Wilderness and Fixed Anchors 46Caves 48››3

CMP Table of Contents ContinuedCHAPTER 6: Climbing Management Methods 49Philosophies and Tools 49Visitor Capacity 50Increase in Climber Visitation 51New Climbing Routes 52CHAPTER 7: Production of a Climbing Management Plan (CMP) 55Suggested Outline of CMP Contents 56Hallmarks of a Successful CMP 56Guidelines for Preparing a CMP 56APPENDICES:A ) Types of Climbing Defined 62B ) Glossary of Climbing Terms 64C ) Outreach and the Development of Education Materials 66D ) Funding and Volunteer Assistance for Climbing Management 68E ) Contacts on Climbing Issues 69F ) Utilizing the Resources of the Access Fund 69G ) Bibliography and References 71CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN Table of ContentsINDEX:››475

CMP ForwardPURPOSE AND NEED FOR THISDOCUMENTThe Access Fund was established in 1990 to resolveissues of climbing access and education. Theorganization provides information, human resources,and grants for access improvements or impactmitigation, and works closely with climbing advocatesand land managers on access issues, resourceprotection, and climbing management initiatives. Withclimbing activity on the increase (Outdoor IndustryFoundation 2006), policies and management plansare being developed throughout the United States thatwill have significant effects on climbing access andexperiences in the future. We intend this documentto assist to those involved or interested in climbingmanagement, and encourage greater consistency inclimbing management policy.This document is intended for use by land managers,recreation planners, and climbing representatives (andany other interested members of the public) who areworking on climbing management issues. It is designedto reach a range of audiences, with widely varyingmanagement experience and needs. This manualintroduces typical climbing-related issues and suggestsmanagement responses that have proven successfulin the past. The level of management will depend onthe mandate of the managing agency, the relativeimportance of climbing compared to other recreationuses in that area, and staffing and budgetary resources.If you have additional information or comments onthis document please contact the Access Fund:info@accessfund.org, (303) 545-6772.Over the past two decades, outdoor recreationactivities that contain the elements of risk andadventure have grown in popularity (Cordell 1999). Theadventure sport of rock climbing, a highly visible anddiverse activity, is no exception to this growth. Morepeople than ever are participating in climbing in itsmany forms—bouldering, sport climbing, ice climbing,big-wall climbing, and mountaineering (Appendix A).The primary resources for climbing include cliffs, talus,glaciers, frozen waterfalls, and boulderfields, whichare found in a variety of environments. Currently, morethan 2,000 climbing areas have been documentedin the United States, with almost half (47%) of thesefound on federal lands (Toula 2003; Stuart-Smith 2003).Participation rates have been on the rise for the past 25years. Beginning in the 1980s, participation in climbingincreased 8% from 1980 to 1984 and 12% between1985 and 1989 (Moser 1990). The 1994-95 NationalSurvey on Recreation and the Environment reported300,00 to 400,000 active rock climbers in the UnitedStates, with this number expected to increase 50percent by year 2050 (Cordell 1999).More than any other issue, the increase in climbervisitation has driven recent discussions about climbingmanagement and the development of climbingmanagement plans. Climbing is as much aboutintimacy with nature and exploration of wild placesas it is about personal challenge. As the number ofclimbers increases, greater demands will be placed onthe vertical and surrounding environments to supportthe various types of climbing activities. As a result,the climbing experience may be diminished whenthe environment is degraded. However, the impactsassociated with climbing activities depend less onthe total number of climbers than on the spatial andtemporal concentrations of climbers in particularareas. Historically, climbers have had a high standardof environmental awareness and stewardship—forexample, climbers such as David Brower wereinstrumental in passing the 1964 Wilderness Act. Mostmanagers will acknowledge that climbers as a groupsupport programs that protect natural resources, aswell as those that protect resources with cultural andhistoric values.››5CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN IntroductionThis document can assist with: Providing an enjoyable public land climbingexperience. Review of issues related to climbing management Production of a climbing management plan Identification of management alternatives to addressclimbing and resource-protection issues Identifying the different recreational values associatedwith climbing. Coordinating with climbing organizations and localclimbing representatives for the purposes of gatheringinformation and participating in development andimplementation of climbing management policy.INTRODUCTION

CMP Chapter 1 A Guide to Climbing ManagementCHAPTER 1: A GUIDE TO CLIMBING MANAGEMENTThis chapter addresses the various climbing management issues andexamples of management responses. Assessment of a Climbing Areaintroduces the reader to issues that have historically appeared whenclimbers begin to use a climbing area in significant numbers.CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN A Guide to Climbing ManagementA Schematic Breakdown of a Climbing AreaIllustration: S. Dieckhoff››6

CMP Chapter 1 Assessment of a Climbing AreaASSESSMENT OF A CLIMBING AREAThis section provides an overview of the uniquemanagement issues related to climbing.The areas affected by a climbing visit can be split into sixzones. Inspecting these individual zones can help clarifyhow, where, and during what stage of a visit climbingactivity may affect rare plants, animals, or archaeologicaldeposits. This scheme can also assist in distinguishingthe effects of climbers from the effects of other lessconspicuous recreation visitors, such as hikers, whomay also frequent the various zones. The zone schemeof assessment and other information-gathering toolscan help ensure that management responses accuratelytarget the correct sites of impact and the use practicesresponsible for impact.In this document, the schematic assessment will beused in the sections on Impacts to Vegetation andCultural Resources. In addition to these sample uses,the scheme can also be applied in the assessment ofother resources or effects mentioned in this document.Site visits and surveys may be carried out periodically torecord effects in each zone. Ideally, some baseline datawill be available from prior inventory and monitoring.This information may then be evaluated in its contextualenvironment to determine whether managementintervention is required.Climbers at the base of Super Crack Buttress, Indian Creek, UT.Photo: Celin SerboA typical climbing visit may be considered to passthrough six zones:1. The approach to the climb (see glossary fortechnical definitions of climbing terminology). The“approach” is the route used to travel from the parkingarea to the base of the rock or mountain. It may or maynot include discernible climber trails.CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN Assesment of a Climbing area2. The staging area. The approach ends at the “stagingarea,” typically the base of the cliff where climbersprepare to climb and sometimes leave backpacks whichwill be retrieved after the descent. In some cases, thestaging area will be at the top of the cliff. Of all the zonesused by climbing visitors, the staging area is typically themost heavily impacted.3. The climb. The “climb,” often called the “route,” isthe line of travel up the cliff or mountain. This zone istypically 6 to 8 feet in width, follows a line that may bestraight or very irregular, depending upon the climbingterrain, and will extend from the base to the summit, orsometimes to a fixed anchor below the summit.4. The summit. The “summit” is either the top of amountain or the rim of a cliff, where one or more climbsterminate.5. The descent. The “descent” is the route by whichclimbers return to either the staging area or to theparking area where their visit originated. In some cases,the descent will involve a climber trail, while in othercases it may entail a rappel down the rock face.6. The camping or bivouac area. This zone is the areaused by climbers for overnight stays during the climbingvisit.››7

CMP Chapter 2 Climbing and Natural Resources Ecological ImpactsCHAPTER 2: CLIMBING AND NATURAL RESOURCESThis chapter introduces and discusses a variety of environmental concerns including trails, camping, human waste,vegetation, water resources, and wildlife.Both resource managers and researchers have reporteda variety of impacts related to rock climbing (Attarianand Pyke 2000). Soil erosion, the development ofsocial trails, damage to vegetation both on and offthe rock, improper disposal of human waste, anddisturbance to wildlife have been reported as a resultof climbing activity. Visual impacts to the rock and itsenvirons, the use of fixed anchors, potential damageto historical and cultural sites, and negative recreationexperiences by non-climbers have also been identifiedas climbing-related concerns. Impacts have thepotential to compromise the objectives of conservingthe natural environment, can make recreation areas lessattractive or functional to the visitor, and can detractfrom the recreation experience through crowding,conflicts between users, and depreciative behavior(Cole 1986; McAvoy and Dustin 1983). The potentialimpacts associated with outdoor recreation activities likerock climbing can be divided into three primary areas:ecological, cultural, and social impacts.The term “impact” was defined by Lucas (1979), asa neutral term synonymous with change. In contrast,“damage” and “deterioration” suggest negative changesin natural resource conditions. However, at least onestudy, Hammitt and Cole (1998), defines “impact”as an undesirable change in environmental or socialcondition of a recreation site or experience. Impacts aredependent on three major factors: (1) the amount anddistribution of use, (2) the type and behavior of visitors,and (3) the ecosystem and its condition (Hendee,Stankey and Lucas 2005).CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN Ecological ImpactsECOLOGICAL IMPACTSEcological impacts are those impacts that havea potential effect on the biological and physicalcharacteristics of a site or resource, thus making thearea less natural (Hendee, Stankey and Lucas 1990).While some climbing impacts are similar to those foundin other recreation environments (for example campingand hiking), managing rock climbing activity posesspecial challenges due to the unique character of theclimbing environment, which is spatially diverse andencompasses both a horizontal and vertical perspective.The ecological issues presented in the following sectionfocus on climber trails, bivouacking and backcountrycamping, human waste disposal, vegetation, waterresources, and wildlife.CLIMBER TRAILSMany of the trails found in park and natural areas wereoriginally designed to serve non-recreational uses.Some of these uses include fire and logging roads,livestock and game trails, and trade and travel routes.››8Climbers use trails to access and egress climbing areas.Unlike hiking trails that are designed, constructed, andmaintained by professionals, some trails to climbingsites are created by climbers when new climbing areasare developed. Climber trails usually “follow the pathof least resistance,” avoiding obstacles and minimizingthe effort to reach a climbing destination (DeBenedetti1990). In some cases trails may be ill-defined causingclimbers to unknowingly take several trails to the samedestination.Sometimes called “social trails,” these trails developas climbers make repeated visits to climbing-specificdestinations that are not serviced by existing trailsystems, or move around in predictable ways within aclimbing area. Typically, climber trails develop in threegeneral locations: 1) along the quickest route from aparking area to the climbing site; 2) on the simplestdescent from the top of a mountain or cliff; and 3) onroutes between cliffs and boulders within the climbingsite (DeBenedetti 1990).The most critical problems associated with trails are soilcompaction, trail widening, trail incision, and soil loss.Trail degradation is usually a function of site durability,type of use, and use behavior rather than simply theamount of use (Leung and Marion 1996). The majority ofenvironmental changes to trails occur during initial traildevelopment. Once a trail becomes established, factorssuch as soil characteristics, topography, ecosystemcharacteristics, climate, and local vegetation’sresistance and resilience will dictate its prominence inthe landscape (Hammitt and Cole 1998). Climber trailstend to be primitive with minimal improvements, areoften sited on steep slopes, with loose soils and “scree”common elements.Climbers, like other outdoor enthusiasts, have thepotential to disturb soil, particularly in heavily used areasor where environmental and other factors cause theseareas to be more susceptible to damage. Damage tosoil can limit aeration, affect soil temperature, moisturecontent, nutrition, and soil micro-organisms. Erosion,the most damaging impact to soil, occurs primarilythrough the development and use of trails. Problemsmay be more serious at higher elevations where the soilis poor and the growing season shorter (Hammitt andCole 1998). Climber trails that are located on soils withhigh gravel or mineral content have been found to beless prone to soil erosion. These materials are not aseasily eroded by water or wind and act as filters, bindingand holding on to finer soil particles (Leung and Marion1996).

CMP Chapter 2 Climbing and Natural Resources Climber TrailsStaging areas and cliff tops are subject to impacts byother recreationsists such as hikers, backpackers, andsightseers (Wood, Lawson and Marion 2006; Williams1990; Long et al. 2003). For example, in California’sYosemite National Park, El Capitan Meadow, locatedjust south of the base of El Capitan, is a popular visitordestination, especially for tourists observing rockclimbers on “El Cap.” Conditions in the meadow arebecoming increasingly degraded, due in part to a lack ofdesignated trails and extensive use of social trails. Soilcompaction in this area has been identified as a potentialproblem (Ortiz 2006).The type of climbing that occurs in an area may alsohave an affect on the amount of impact an area receives.Recent research conducted in Kentucky’s Red RiverGorge found impacts to staging areas are different forsport and traditional (“trad”) climbing. Trail quality, thenumber of similarly rated climbs in the area, and thepresence of overhanging rock were found to contributeto staging area impacts for sport climbs. Factorscontributing to impacts associated with traditionalclimbs, on the other hand, include the rating of the climb,climb quality, approach trail length, and the presence ofoverhanging rock (Carr 2006).Soils in arid environments like those found in JoshuaTree National Park, CA, and in Arches and CanyonlandsNational Parks, UT, may contain cryptobiotic crusts,which consist of mosses, lichens and blue-green algaeknown as cynobacteria. These crusts are importantto the environment, since they increase the waterholding capacity of soil, increase nutrient cycling, limitthe invasion of weedy, non-native annual grasses,and reduce soil erosion. Any type of disturbance—forexample hiking and climbing—can compromise thesediment associated with these crusts (Overlin et al.1999).CLIMBER TRAILSIf many climbers use an area, some degree offormalization and stabilization of climber trails willeventually become desirable. Some climber trailsmay be redundant or adversely affect resource oraesthetic values. Such trails can be minimized or insome cases eliminated. Local climbing representativescan provide input on the minimum trail requirementsto access climbing locations. Management responsemay initially include conducting a climber trail inventory.Local climbing guidebooks will often describe climberaccess routes, descent routes, and locations of otherclimbing-related trails. Consultation with a local climbingrepresentative or arranging a joint site visit may also helpwith climber-trail inventory.Local climbing representatives may prove helpful indispersing information concerning desired changes inclimber-trail use. Other management options includesigning of management-preferred trails, and brochure,kiosk, and poster information concerning site advisoriesor area closures. There have been many examples ofsuccessful climber trail management. At City of RocksNational Reserve, ID, climbers and hikers originally used(and then expanded) livestock trails through sagebrushvegetation. A park-wide trails plan was developed toidentify a rational trails network and mitigate impacts(U.S. Department of the Interior 1988).At Joshua Tree National Park, CA, climber-trail networkshave been formalized using a special climber-specificsymbol. This is produced in the form of a weatherresistant sticker that can be applied to standard trailmarking carsonite posts.The symbol (an image of a carabiner—a piece ofclimbing equipment) is recognizable to climbers, butnot the general public (Joshua Tree National Park et al.2000).At Joshua Tree National Park, CA. A special climbingsymbol is used on standard path–marking carsoniteposts to mark climbing access trails. These signs onthe approach to the Hall of Horrors climbing area directvisitors and reduce the development of duplicate trails.Photo: The Access Fund Collection››9CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN Climber TrailsMANAGEMENT PRACTICES THAT WORKOnce trails are documented (typically GPS techniquesare used), a map is created. If necessary, a trails plancan be developed to eliminate redundant or unnecessarytrails. Some trails may be targeted for stabilization orupgrading to withstand heavier traffic, while others maybe closed to protect sensitive resources, and replacedwith new, re-routed trails. This approach was taken bymanagers in North Cascades National Park, WA, torestore the Eldorado Creek drainage, a popular routeused by climbers to access the Eldorado Glacier. Theroute had become deeply rutted and eroded. Followingan environmental assessment, a 1,300 foot section ofthe trail was rerouted to divert climbers to more resilientterrain which could withstand impacts that the damagedarea could not. This project was the first attempt bythe park to rehabilitate recreational climbing impacts ina cross-country or non-trailed area. (North CascadesNational Park 1997).

CMP Chapter 2 Climbing and Natural Resources Bivouac and Backcountry CampingBIVOUAC AND BACKCOUNTRY CAMPINGCamping or bivouacking may be required as part ofa climbing objective. This may take place either onthe approach, on the climb itself, or on the descent.Unplanned bivouacs are not uncommon, and typicallyoccur after a long backcountry route not completedby nightfall. Climbing in the interior of mountain rangesor on remote cliffs usually requires a planned campingexperience to put the climbers in position to do a longroute requiring an early start. Sometimes there will bea need to camp for several days in one area if a longand challenging route is intended (which might requireseveral attempts), or if there are several route objectivesin the area. Climbing on some of the large cliff facesof Yosemite, Zion, Rocky Mountain, and Black Canyonof the Gunnison National Parks may require bivouacson the climb itself. Hanging tents called “portaledges”provide shelter and are designed to withstand minorstorms during a multi-day climbing ascent.MANAGEMENT PRACTICES THAT WORKCLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN Bivouac and Backcountry CampingVolunteers on a trail-building project at North TableMountain, Colorado. Funding for materials andtrail design can also be obtained from climbingorganizations. Photo: Access Fund Collection“Cryptic” trails have also been used to limit non-climberaccess in areas with sensitive habitat. Such trails aredesignated on a park-wide trails plan but not signedto the general public. This technique has been usedat Snow Canyon State Park, UT, to allow climbingaccess to Hidden Canyon, a narrow riparian canyonwith high ecological value. Climber trails may see lowtraffic volume or access steep and difficult terrain,and thus may merit special design and maintenancespecifications that would be inappropriate for highvolume multi-visitor use trails. Collaboration betweenpark management and the climbing communityimproved trails, created belay platforms, and erecteddirectional signs at Smith Rock State Park, OR,to control trail erosion and enhance the climbingexperience.Permits are required for overnight bivouacsin Rocky Mountain National Park to accesspopular alpine climbing areas such as thePetit Grepon. At the backcountry rangeroffice, permit holders are provided with amapped location of the site they shoulduse and information on minimizing impactsat bivouac sites. Photo: K. Pyke››10As climbing becomes more popular, climbersvisiting well known climbing areas will require additionalcamping areas. Climbers in the New River GorgeNational River, WV, and the Obed Wild and Scenic River,TN, have indicated a need for public campgrounds.The American Alpine Club is working with the MohonkPreserve and the state of New York in developing aclimbers’ campground. Under the proposal, the statewould assist in the development of a 45-acre, 20-sitecampground scheduled to open in 2008 (AmericanAlpine Club 2005).

CMP Chapter 2 Climbing and Natural Resources Human Waste DisposalBivouacking must be considered a fundamental aspectof the climbing experience in many areas. If the areareceives a high level of use, management responsemay include outreach to ensure low-impact practices,site monitoring, the designation of bivouac sites,permit requirements, or, occasionally, the provision of aprimitive facility in order to reduce human impacts overa wider area. For a sample of a heavily used area, seethe backcountry camping and bivouac policy for RockyMountain National Park, CO (Table 1).Table 1.Bivouac Permit Rocky Mountain National ParkA bivouac is a temporary, open-air encampmentestablished between dusk and dawn and is issued onlyto technical climbers. The permit also provides technicalclimbers with an advanced position on long, one-dayclimbs and/or climbs that require an overnight stay onthe rock face. All bivouacs require permits. Permits mustbe in your possession while in the backcountry.You must be within a designated bivouac area. Yourbivouac should on a durable surface such as rock orsnow as close to the base of the climb as possible or

forms of climbing—rock climbing, ice climbing, mountaineering, and bouldering—the Access Fund is the largest US climbing organization with over 15,000 members and affi liates. The Access Fu