Transcription

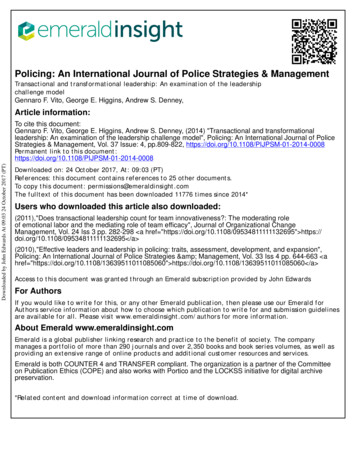

Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & ManagementTransactional and transformational leadership: An examination of the leadershipchallenge modelGennaro F. Vito, George E. Higgins, Andrew S. Denney,Article information:Downloaded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)To cite this document:Gennaro F. Vito, George E. Higgins, Andrew S. Denney, (2014) "Transactional and transformationalleadership: An examination of the leadership challenge model", Policing: An International Journal of PoliceStrategies & Management, Vol. 37 Issue: 4, pp.809-822, nt link to this 08Downloaded on: 24 October 2017, At: 09:03 (PT)References: this document contains references to 25 other documents.To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.comThe fulltext of this document has been downloaded 11776 times since 2014*Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:(2011),"Does transactional leadership count for team innovativeness?: The moderating roleof emotional labor and the mediating role of team efficacy", Journal of Organizational ChangeManagement, Vol. 24 Iss 3 pp. 282-298 a href "https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811111132695" https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811111132695 /a (2010),"Effective leaders and leadership in policing: traits, assessment, development, and expansion",Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, Vol. 33 Iss 4 pp. 644-663 ahref "https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511011085060" https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511011085060 /a Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by John EdwardsFor AuthorsIf you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald forAuthors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelinesare available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.comEmerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The companymanages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well asproviding an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services.Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committeeon Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archivepreservation.*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available l andtransformational leadershipAn examination of the leadershipchallenge modelGennaro F. Vito, George E. Higgins and Andrew S. DenneyDepartment of Justice Administration, University of Louisville, Louisville,Kentucky, ceived 17 January 2014Revised 14 April 201427 July 2014Accepted 27 July 2014Downloaded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)AbstractPurpose – The purpose of this paper is to examine three different structural models the LeadershipChallenge model to determine if they best capture transactional or transformational leadership.The three models are derived from the literature.Design/methodology/approach – The data for this study come from self-report surveys of middlemanagers that are attending the Administrative Officers Course at the Southern Police Institute.The managers completed the 30-item 3601 leadership challenge measure. Because the leadershipchallenge measure is a 3601 evaluation of leadership, up to five observers provided data about theirmanager. The authors use the data from the observer in this study. Using structural equationmodeling, the authors examine the aims.Findings – The findings show two important advances. First, the leadership challenge model maycapture both transformational and transactional leadership. Second, the findings support the view thatthe really captures transformational leadership.Originality/value – To the authors’ knowledge, no study has performed this type of examination inthe policing literature. The value of this type examination is high.Keywords Police, LeadershipPaper type Research paperLeadership is an important function for police managers. It is instructive to thinkof leadership in a series of functions. Police managers formulate and refine theorganization’s mission, goals, and objectives in terms of perceived needs. This requiresthe police managers handle departmental resources, motivate personnel to achievegoals and objectives, set a moral and professional tone, and create an environment forefficient, effective, and productive work (see More et al., 2012, pp. 60-61). No one way tolead a policing organization exists. Burns (1978) presented two ways, however, thatare available, for police managers to use, are transactional and transformationalleadership.Transactional leadershipBurns (1978) argues that individuals in an organization may be influenced andmotivated by leaders. Burns (1978) outlines the leadership process two, theoretical,components: transformational and transactional leadership. Generally, each of thesetypes of leadership has different ways to influence attitudes and motivation.Burns (1978) idea of transactional leadership has its roots in social psychologicalsocial exchange theory. This form of leadership relies on the reciprocal and deterministicrelationship between a leader and their subordinate(s) (Burns, 1978; Bass, 1981, 1985,1997; Bass and Riggio, 2006; Judge and Piccolo, 2004). To clarify, leaders use a bargainingprocess with subordinates to motivate behavior. Utilizing relative positional power,Policing: An International Journal ofPolice Strategies & ManagementVol. 37 No. 4, 2014pp. 809-822r Emerald Group Publishing Limited1363-951XDOI 10.1108/PIJPSM-01-2014-0008

PIJPSM37,4Downloaded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)810the leader regulates the bargaining process so that benefits may be issued and receivedto continue positively valued behavior.Transactional leadership is characterized in multiple ways. First, a transactionalleader utilizes contingent rewards (e.g. work for pay or time off) to underlie thearrangements for explicit or implicit agreement on goals to be reached to obtain thedesired rewards or behavior (Bass, 1981, 1985, 1997). Second, the transactional leaderuses a management-by-exception format to implement a monitoring program thatallows them to gather behavioral information to predict or prevent the subordinatefrom deviating from the agreed upon goals of objectives (Bass, 1981, 1985, 1997). Third,transactional leaders are generally passive and only take action when a problem arises(Judge and Piccolo, 2004).Under this perspective, leaders and subordinates have considerable power andinfluence. The mutually beneficial exchange that takes place to obtain goals supportsthis view (Bass, 1981, 1985, 1997; Judge and Piccolo, 2004). Situations may arisewhere a leader being privy to vital information or a subordinate may have specializedproblem-solving skills that put each into a leveraging position for negotiation;thus, valuable time may be squandered because negotiations are occurring rather thanproductivity. Unfortunately, this type of exchange may only garner short-termcommitment.Transformational leadershipThe transformational leadership theory also makes provisions for power and influencein the leadership process as the transactional leadership theory. According to Burns(1978), the relationship between the leader and the subordinate is based on emotion.The leader utilizes the trust and confidence that the subordinate places in them tomotivate behavior (Bass, 1981, 1985, 1997). Transformational leaders typically rely onfour characteristics: charisma, inspiration, individual consideration, and intellectualstimulation (Bass, 1981, 1985, 1997).The transformational leader uses these characteristics to motivate behavior.For instance, the transformational leader uses their charisma to create a sense ofreferent power (Bass, 1985). Here, the subordinate puts themselves into a positionwhere they have a strong need for leader approval, and they do not criticize (Burns,1978; Bass and Riggio, 2006; Villiers, 2003, p. 33). Transformational leaders are able toinspire subordinates by connecting with them emotionally, which provides theopportunity to share a vision. The emotional connection with the subordinate does notend with inspiration. A transformational leader uses this connection to serve as amentor or developer demonstrating to the subordinate a focus on them (i.e. individualconsideration). The transformational leader encourages the intellectual stimulation oftheir subordinates. In this area, the transformational leader assists or mentors thesubordinates in questioning the status quo, or thinking of old problems in new ways(Bass, 1985; Reese, 2005, pp. 24-25).The transformational leader optimizes his or her power and influence usingcharisma or vision. Bass (1985) argues that subordinates are less likely to influence theleader because they are placed on a pedestal. This does not discount the possiblevalues of individual consideration or intellectual stimulation as possible influenceson the subordinate.Transformational leaders are present in police organizations. In his assessment ofleadership in the Los Angeles police department, Reese (2005, p. 132) identified ChiefWilliam Bratton as a transformational leader due to his intellectual vision, empathy for

Downloaded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)his officers and the community as well as his personal charisma and communicationskills. Empirically, transformational leadership has been a focus of studies on policeleadership. Murphy and Drodge (2004) interviewed 28 Royal Canadian Mounted Policeofficers on their views of police leadership within the framework of transformationalleadership theory. The RCMP officers stressed that leaders can emerge at all levels ofthe organization and that leadership skills can be learned.Murphy (2008) used an auto-ethonographic approach to gather leadership informationfrom large municipal police departments. The results indicate that emotions are anintegral part of police leadership. Specifically, leaders that formed an emotionalattachment with their officers and “walked the talk” are able to use transformationalleadership effectively.Leadership challenge modelAnother way of viewing leadership is through the Leadership Challenge Model(Kouzes and Posner, 2012). Kouzes and Posner (2012) argue that the five principles ofleadership are as follows:(1)Model the Way.(2)Inspire a Shared Vision.(3)Challenge the Process.(4)Enable Others to Act.(5)Encourage the Heart.In addition, each of the Five Principles contain “Ten Commitments” that specify whatactions leaders typically take to achieve them.Commitment 1 under “Model the Way” states that leaders must find their voice byclarifying their values because they influence how leaders respond to their followers.Expressing genuine values to followers empowers and motivates them to accomplishwhat needs to be done. Commitment 2 signifies the competence of the leader bydemonstrating their ability to act in alignment with their expressed values. In turn, thisaction sets an example for followers and helps build consensus among them. Leaderscan also reinforce values through storytelling and bringing values to life.In the second practice, leaders inspire a shared vision with followers. Commitment 3states that leaders accomplish this by imaging exciting and ennobling possibilities.Commitment 4 requires that leaders bring their vision to life by appealing to the sharedaspirations of the followers.In the third practice, “Challenging the Process,” the leader seizes the initiative andmakes improvements in the organization with the active participation of the followers.Accordingly, Commitment 5 states that leaders seek innovative ways to change, growand improve. Leaders encourage experiments and sponsor the courage of followers totake risks and seek out opportunities to make change happen. As a result, leaders donot chastise and punish followers when they take risks to move the organizationforward. Instead, they encourage them to learn from and improve upon their mistakes.The fourth practice is “Enabling Others to Act.” Leaders trust their followers tocomplete tasks effectively. They do not seek power or status and recognize thatfollowers must feel the need to take the initiative and act upon it. Under Commitment 7,leaders foster collaboration by promoting trust and collaborative goals for theorganization. They inspire their followers to solve their own problems and thus buildTransactionalandtransformationalleadership811

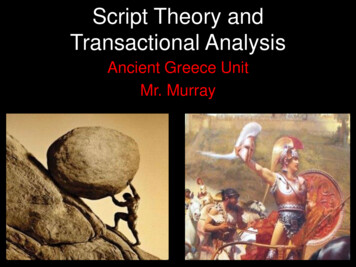

PIJPSM37,4Downloaded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)812confidence and competence. Commitment 8 relates to this practice by sharing powerand discretion with followers.The fifth and final practice is “Encouraging the Heart.” Leaders set high standardsand hold followers accountable but they also take the time to celebrateaccomplishments. Commitments 9 and 10 states that effective leaders accomplishthese tasks via public gatherings that communicate what positive performance looklike and create a spirit of community within the organization.In sum, Kouzes and Posner use the information that come from the 3601 evaluation(i.e. the individual completes the SLCI (self) and then nominates observers to completethe SLCI (observer)) to suggest that leaders who have followed these tenets have beensuccessful and that others can learn from their example. Persons who accept thisleadership challenge (i.e. information from their observers) and adopt these methodscan move their organizations forward as well.An interesting issue comes up in the leadership literature, the distinction betweentransformational and transactional leadership is not clear. Research from 3601evaluations show that some observers can make the distinction between the two typesof leadership (Yammarino and Atwater, 1993; Yammarino and Dubinsky, 1994;Atwater et al., 2006), but other research shows that the observers are not able to makethis distinction (Scandura and Schriesheim, 1994). These studies do have an importantsystematic difference; they used different leadership scales. The differences in thedistinction may be a manifestation of these different scales.Kouzes and Posner (2012) argue that their LPI captures transformational leadership.A close inspection of five principles of the LPI suggests that they are capturing keyparts of transformational leadership. The research, however, shows mixed results.Fields and Herold’s (1997) survey study assesses whether transactional andtransformational leadership can be inferred from subordinate reports of leadershipbehaviors in a 3601 evaluation. For this assessment, they used the LPI. Fields andHerold (1997) show that transactional and transformational leadership are underlyingdimensions of the five LPI dimensions. Consistent with previous research (Scanduraand Schriesheim, 1994), they show that the distinction between the two types ofleadership is not clear in these data. Their results show that encouraging the heart andmodeling the way fit best for both transformational and transactional leadership.Carless (2001) examined the construct validity of the LPI to determine if it wasa single, multiple, or hierarchical measure of transformational leadership. Using datafrom over 1,400 subordinates, the results show the greatest support for a hierarchicalmodel of transformational leadership. In other words, the items formed the five factorsof the LPI, and these five factors indicate an overall measure of transformationalleadership. Therefore, the mixed results from the research suggest that a compellingstudy would be to address this issue.The present studyFields and Herold (1997) suggest that subordinates are not able to distinguish betweentransformational and transactional leadership because the measures of the LPI overlapwhen indicating these leadership styles. However, Carless (2001) shows that subordinatesindicate that the LPI creates a hierarchical measure of transformational leadership.The present study is a test of this suggestion using responses to the LPI from observersof police managers. The aim is to examine whether the LPI can be indicatorsof transformational and transactional leadership. Model 1 in Figure 1 shows thisassumption. Following Fields and Herold (1997), we assume that challenge the process,

aded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)Challengethe ProcessInspire aSharedVisionEncouragethe HeartEnable Othersto ActTransformationalLeadershipChallengethe ProcessInspire aSharedVisionModel theWayTransactionalLeadershipModel theWayModel theWayEnableOthers toActEncouragethe HeartTransformationalLeadershipChallengethe ProcessInspireaSharedVisionEncouragethe HeartModel theWayEnableOthersto Actinspire a shared vision, and encourage the heart are indicators of transformationalleadership. We also assume enable others to act and model the way are indicators oftransactional leadership.The second aim is to examine whether the observers are able to make distinctionsbetween transformational and transactional leadership. Model 2 in Figure 1shows our assumptions. Similar to Fields and Herold (1997), our Model 2 differsfrom Model 1 assuming that model the way may be an indicator for both formsof leadership.The third aim is to examine whether the observers see the items of the LPI as ameasure of transformational leadership similar to Carless (2001). This is accomplishedFigure 1.Three models oftransactional andtransformationalleadership

PIJPSM37,4Downloaded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)814by examining whether measures of the five principles indicate a unidimensionalmeasure. Model 3 shows this model.MethodsSample and proceduresThe present study analyzes responses from a 3601 assessment of the leadershipperformance of police managers attending the Administrative Officer’s Course at theSouthern Police Institute at the University of Louisville. As a part of their course onleadership at the AOC, these police manager students were asked to fill out aself-assessment of their leadership strengths and weaknesses as posed by the modelpresented in Kouzes and Posner’s (2012) work, The Leadership Challenge and listed intheir assessment document, The Student Leadership Challenge Inventory (SCLI –Kouzes and Posner, 1998). This scale was developed by Kouzes and Posner to assesshow student respondents evidenced behaviors and practices associated with the fiveelements of The Leadership Challenge model:(1)Model the Way.(2)Inspire a Shared Vision.(3)Challenge the Process.(4)Enabling Others to Act.(5)Encourage the Heart.These elements reflect the practices and methods followed by successful leaders. TheSLCI itself consists of two forms – the Self and the Observer. The scales on the formsare identical with six statements designed to measure each of the five elements listedabove. The difference between them is in their application. The Self SCLI is completedby the leader while the Observer SCLI is completed by a subordinate and/or superior.Thus, they both assess the leadership qualities of the person in question in the form ofa 3601 evaluation. Studies using the LPI have demonstrated its validity and reliabilityin measuring these leadership practices with a number of different populations,including students, business and police managers (Posner, 2004; Carless, 2001;Zagorsek et al., 2006; Vito and Higgins, 2010).The police manager students filled out a “Self” portion of this instrument while acopy of the “Observer” instrument was sent to three subordinates and three superiorsin their agency. The anonymous Observer instrument responses were mailed by thecourse instructor and were returned to his office. Our research sample consists ofthe survey results from six AOC classes (n ¼ 291) and 1,659 Observers. The responserate from the Observers was 95 percent.The sample is constrained to 1,659 observers[1]. The sample is 81.3 percent(n ¼ 1,348) male, and white 87.4 percent (n ¼ 1,390). The mean rank is Captain (M ¼ 5.45,n ¼ 247), but the modal category for rank is sergeant (19.8 percent, n ¼ 328). The averageeducation level is college graduate (M ¼ 5.03 or 38.5 percent). The average age is 43.37years old. The average number of sworn police officers is 16.17 in their department.MeasureThe measure for the study is Kouzes and Posner’s (2012) version of the LeadershipPractices Inventory. The measure contains 30-items for each of the five leadershipprinciples (see the Appendix for the complete listing of the items).

Downloaded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)Analysis planThe analysis plan takes place in two steps. The first step is a presentation of thebivariate correlations for these data. These correlations show whether the dimensionsof the LPI share variation.The second step is a presentation of the measurement model using structuralequation modeling. Within the structural equation modeling process, we useconfirmatory factor analysis. Figure 1 provides our a priori assumptions about how themeasures from the LPI may be indicators of transformational and transactionalleadership. Following Kline (2011), the a priori nature of our assumptions makes CFA aviable means of analysis. In the second step, we examine a number of fit statistics,and follow Hu and Bentler’s (1999) recommendations. We begin by examining the w2statistic that should not be statistically significant. Hu and Bentler (1999) showthat the w2 statistic is likely to be significant because the sample size is relativelylarge. Therefore, we examine multiple fit statistics: comparative fit index (p0.95),RMSEA (p0.05), and SRMR (p0.05). In addition to the fit statistics, we followKline’s (2011) recommendation that large factor loadings are above 0.50. A properlyfitting model that reveals strong factor loadings is an indication that the leadershipchallenge inventory items represent latent measures of transformational andtransactional hip815ResultsStep 1Table I shows the bivariate correlations for each of the five measures show highcorrelations. For instance, modeling the way has high correlations with all of theother four measures (r ¼ 0.69-0.83). In addition, inspiring a shared vision has highcorrelations with all of the other measures (r ¼ 0.62-0.83). Further, challenging theprocess has high correlations with all of the other measures (r ¼ 0.64-0.83). Enablingothers to act has high correlations as well (r ¼ 0.62-0.74). Finally, encouraging the heartalso has high correlations (r ¼ 0.67-0.74). Additional modeling is necessary tounderstand how these high correlations come together. Specifically, it is importantto address whether our beliefs that these correlations are caused by latent measures oftransformational and transactional leadership.Step 2Table II presents the measurement model that uses confirmatory factor analysis.This model examines whether challenging the process, inspiring a shared vision, andMeasures1. Model the Way2. Inspire a Shared Vision3. Challenge the Process4. Enable Others to Act5. Encourage the HeartMeanSDNote: ** 3.791.000.74**24.383.591.0024.044.09Table I.Bivariate correlations anddescriptive statistics

PIJPSM37,4Model 1MeasuresDownloaded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)816Table II.Confirmatory factoranalysesTransformationalleadershipEnable Othersto ActInspire a SharedVisionChallenge the ProcessTransactionalleadershipModel the WayEncourage the Heartw2 ¼ 443.19**CFI ¼ 0.95RMSEA ¼ 0.24SRMR ¼ 0.04Model 2Factorloading onalleadershipInspire a SharedVisionChallenge theProcessModel the WayTransactionalleadershipModel the WayEncourage theHeartEnable Othersto Actw2 ¼ 32.11**CFI ¼ 0.99RMSEA ¼ 0.09SRMR ¼ 0.02Model 3Factorloading ipInspire a Shared VisionChallenge the ProcessModel the WayEncourage the HeartEnable Others to **0.89**0.83**w2 ¼ 32.11**CFI ¼ 0.99RMSEA ¼ 0.07SRMR ¼ 0.01Note: ** po0.01encouraging the heart are caused by the latent measure transformational leadership,and whether modeling the way and enabling others to act is caused by transactionalleadership, as in Model 1. The results of the measurement model show that the modelfits the data (w2 ¼ 443.19 ( p ¼ 0.00) CFI ¼ 0.95; RMSEA ¼ 0.24; SRMR ¼ 0.04). The w2and the RMSEA indicate that this model does not fit the data. All of the factor loadingsare strong. Specifically, all of the factor loadings for are above Kline’s (2011) mark of0.50 except for two measures. Regardless of the size of the factor loadings, the modeldoes not fit the data not supporting our hypothesis. The problem with the model fitoccurs because not enough data is present leading to identification problems. The issuehere is the number of observed measures (i.e. measures of leadership challenge) that areeligible to be caused by the latent measures. According to Kline (2011) at least three,but optimally more, observed measures are needed to properly identify a model inconfirmatory factor analysis. In other words, the model does not have enoughinformation for proper identification, and is not supportive that the five principles aredistinct in their measurement of transformational and transactional leadership asshown in Fields and Herold (1997).Table II examines whether challenging the process, inspiring a shared vision, andmodeling the way are caused by the latent measure transformational leadership,and whether encouraging the heart, modeling the way and enabling others to actbehaves as in Model 2. Unlike the measurement model, the structural model does fit thedata (w2 ¼ 31.31 ( p ¼ 0.00); CFI ¼ 0.99; RMSEA ¼ 0.07; SRMR ¼ 0.01). The model fitsthe data properly. In addition, all of the factor loadings are strong. These resultssupport our view that the leadership challenge inventory may serve as indicators oftransactional and transformational leadership. Further, these results indicate thatthe observers are not clear about the distinction between transactional andtransformational leadership. This is supportive Field and Herold’s (1997)

Downloaded by John Edwards At 09:03 24 October 2017 (PT)assumption that the LPI provides information for both transformational andtransactional leadership.Table II examines our assumption that the LPI five principles provide informationon transformational leadership. The fit between Model 3 and the data are the best ofthe three. The w2 is significant (32.11, p ¼ 0.00). The CFI is acceptable at 0.99. TheRMSEA is acceptable at 0.07, and the SRMR is acceptable at 0.01. The standardizedfactor loadings are above 0.50. In fact, the smallest is 0.73 suggesting that the fiveprinciples are capturing information for a unidimensional trait. This is support that theLPI is actually capturing information about transformational leadership, which issupportive Carless (2001).DiscussionBurns (1978) argues that leadership may occur in two ways: transactional andtransformational. To determine if this theory of leadership has come to fruitionin police organizations, the measurement of these concepts needs to be examinedand developed. Kouzes and Posner’s (2012) version of the Leadership PracticesInventory may provide some indication of this leadership theory, which wasthe aim of the theory. Using structural equation modeling, three importantresults come from these data. First, the LPI dimensions may indicators oftransformational and transactional leadership. However, their indication is notclear. The second result show that the observers believe that “modeling the way” isnot only part of transformational leadership, but it is also part of transactionalleadership. Third, the best way to understand the LPI is as a measure oftransformational leadership.Our results do appear to partially replicate Field and Herold’s (1997) results.They show that the LPI dimensions are indicators of transformational andtransactional leadership. In their sample of subordinates, they show that the LPIdimensions do not clearly distinguish between transformational and transactionalleadership. Specifically, in their study, not only did the “modeling the way”dimension cause confusion in these two types of leadership, but “encouragingthe heart did as well.” In the present study, the only dimension that causesthis type of confusion of leadership styles is “modeling the way.” Modeling the wayis when the leader is to “walk the walk.” In other words, the leader has to beable to follow through on the issues that arise in the manner that is proper to theleadership style.The results from the present study imply, for police leadership, that the LPI can be ameasure of these two types of leadership. Special attention needs to be paid to the“modeling the way dimension.” When researchers or leaders wish to use the LPIin this manner, they have to recognize that the “modeling the way” dimension mayhave different meanings based on the type of leadership under study or beingused. The researcher or leader needs to become intentional in their use of the “modelingthe way” dimension of the LPI. Further research is required to provide specificinformation as what “modeling the way” actually means for the different typesof leadership.Additional results support our contention that the five factors of the LPI mayform a unidimensional measure. The unidimensional measure is of tr

The managers completed the 30-item 3601 leadership challenge measure. Because the leadership challenge measure is a 3601 evaluation of leadership, up to five observers provided data about their manager. The authors use the data from the observer in this study. Using st