Transcription

Cybersecurity Workforce Competencies:Preparing Tomorrow’s Risk-Ready Professionals

About UsAbout Apollo Education Group, Inc.Apollo Education Group, Inc. is one of the world’s largest privateeducation providers and has been in the education business since1973. Through its subsidiaries: Apollo Global, College for FinancialPlanning, University of Phoenix, and Western International University,Apollo Education Group offers innovative and distinctive educationalprograms and services, online and on-campus, at the undergraduate,master’s and doctoral levels. Its educational programs and servicesare offered throughout the United States and in Europe, Australia,Latin America, Africa and Asia, as well as online throughout the world.For more information about Apollo Education Group, Inc. and itssubsidiaries, call (800) 990.APOL or visit the Company’s website atwww.apollo.edu.About University of Phoenix University of Phoenix is constantly innovating to help workingadults move efficiently from education to careers in a rapidly changing world. Flexible schedules, relevant and engaging courses,and interactive learning can help students more effectively pursuecareer and personal aspirations while balancing their busy lives. As asubsidiary of Apollo Education Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: APOL), Universityof Phoenix serves a diverse student population, offering associate,bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degree programs from campusesand learning centers across the U.S. as well as online throughout theworld. For more information, visit www.phoenix.edu.The College of Information Systems and Technology atUniversity of Phoenix offers industry-aligned certificates as well as associate, bachelor’s, and master’s degree programs designed to equipstudents for successful IT careers. Through the College’s StackTrack program, students can obtain “en route” certificates while workingtoward a degree, without increasing cost or time to graduation. TheCollege’s interactive curriculum gives students virtual access to toolscommonly used by IT professionals and to training courseware thatfurther prepares students for industry certification. For moreinformation, visit phoenix.edu/technology.About (ISC)2 Formed in 1989 and celebrating its 25th anniversary, (ISC)2 is thelargest not-for-profit membership body of certified informationand software security professionals worldwide, with 100,000members in more than 160 countries. Globally recognized as the GoldStandard, (ISC)2 issues the Certified Information Systems SecurityProfessional (CISSP ) and related concentrations, as well as theCertified Secure Software Lifecycle Professional (CSSLP ), theCertified Cyber Forensics Professional (CCFP ), Certified AuthorizationProfessional (CAP ), HealthCare Information Security and PrivacyPractitioner (HCISPPSM), and Systems Security Certified Practitioner(SSCP ) credentials to qualifying candidates. (ISC)2’s certifications areamong the first information technology credentials to meet thestringent requirements of ISO/IEC Standard 17024, a globalbenchmark for assessing and certifying personnel. (ISC)2 also offerseducation programs and services based on its CBK , a compendiumof information and software security topics. More information isavailable at www.isc2.org.About the (ISC)2 FoundationThe (ISC)2 Foundation is a non-profit charitable trust that aimsto empower students, teachers, and the general public to secure theironline life by supporting cybersecurity education and awareness inthe community through its programs and the efforts of its members.Through the (ISC)2 Foundation, (ISC)2’s global membership of 100,000information and software security professionals seek to ensure thatchildren everywhere have a positive, productive, and safe experienceonline, to spur the development of the next generation of cybersecurity professionals, and to illuminate major issues facing the industrynow and in the future. For more information, please visitwww.isc2cares.org.(ISC)2 Inc., (ISC)2, CISSP, ISSAP, ISSMP, ISSEP, CSSLP, CAP, SSCP, CCFP and CBK are registered marks, and HCISPP is a service mark, of (ISC)2, Inc.

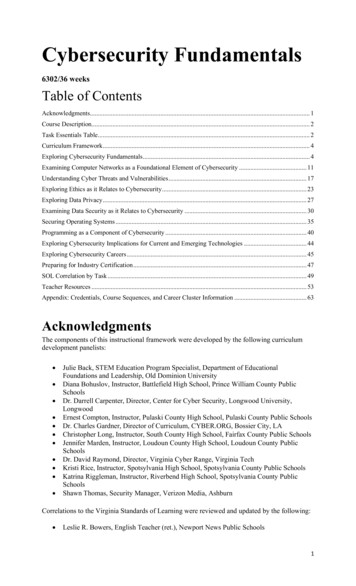

About This ReportThis report is based on the findings from an industry roundtablewith cybersecurity professionals and talent development leaders,co-hosted by University of Phoenix and the (ISC)2 Foundation. Theobjective of the session—part of an ongoing effort to investigate thecompetencies and career priorities of cybersecurity professionals—was to identify actionable recommendations for key stakeholders tobetter prepare students to enter careers in cybersecurity. The focuswas on identifying what educational institutions, employers, industryassociations, and students can do to bridge three education-to-workforce gaps: a competency gap, a professional experience gap, and aneducation speed-to-market gap.Roundtable participants included representatives from institutions ofhigher education that educate cybersecurity professionals;organizations that employ cybersecurity professionals; industryassociations that support and provide certifications to cybersecurityprofessionals; and the U.S. Department of Labor, which developsresearch and tools for workforce prosperity and advancement. Theroundtable also incorporated the perspective of a cybersecuritystudent/career-starter on higher education practices and career entry.Cybersecurity experts and other thought leaders with relevantexperience in competency modeling, higher education,cybersecurity services, and cybersecurity credentialing engaged infacilitated discussion and participated in breakout sessions to identifyactionable recommendations for better preparing the future cybersecurity workforce. This report summarizes those recommendations.The findings are designed to be useful to the larger community ofindustry leaders, employers, educators, and current or futurecybersecurity professionals.ContentsExecutive Summary2Introduction: CybersecurityIndustry Snapshot3Career Opportunities in theCybersecurity Industry5Defining a Common Set of CybersecurityProfessional Competencies6Three Education-to-Workforce Gaps8Closing the GapsRecommendations to Close the Competency GapRecommendations to Close the ProfessionalExperience GapRecommendations to Close the EducationSpeed-to-Market GapHigh-Priority Action ItemsLooking AheadAcknowledgmentsLearn More991011121213131

Executive SummaryThe need for cybersecurity professionals is rising as individuals,organizations, and industries increasingly use data networks forbusiness, commerce, and protection of sensitive information. With thefrequency, sophistication, and cost of cyberattacks on the rise,investing in wide-scale cybersecurity has become a priority forcorporate and public leaders.Although the cybersecurity field is growing quickly and offerscompetitive pay, demand for these IT specialists exceeds thesupply of credentialed, experienced professionals. To aid inbuilding a pipeline of cybersecurity talent, industry leaders are callingfor a common definition of the scope of cybersecurity work and thecompetencies that job candidates must demonstrate.Establishing Cybersecurity Professional CompetenciesTwo sets of competencies—the National Initiative for CybersecurityEducation (NICE) National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework, andthe U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) Cybersecurity IndustryCompetency Model—have been developed to standardizeprofessional requirements.The NICE Framework defines seven categories of typical job duties,covering cybersecurity work in 31 specialty areas across industriesand job types. The DOL’s model expands this Framework to includethe competencies required at various career tiers. It includes softskills, technical and functional competencies for specific sectors andthe overall profession, and management and occupation-specificrequirements.2Closing Education-to-Workforce GapsStakeholders have identified three education-to-workforce gapsthat are hindering efforts to fill cybersecurity jobs with qualifiedworkers. These include gaps in competency, professionalexperience, and education speed-to-market. The report includesrecommendations for employers, industry associations, highereducation institutions, and cybersecurity students to play a role inclosing the gaps. The recommendations are designed to improvealignment of educational content with workplace problems; boost theemployability and ethics of cybersecurity students and aspiringprofessionals; and foster continuous professional developmentthrough networking, organizational memberships, and certifications.Stakeholders have also defined the action items that could havethe most immediate impact on closing the gaps: Higher education programs should integrate problem-basedlearning via case studies and labs. Higher education institutions should partner with employersto promote internships for cybersecurity degree completion. Students should seek stakeholder guidance and takeappropriate steps to position themselves for employment.

Introduction: CybersecurityIndustry SnapshotCybersecurity, or the practice of protecting electronic data fromunlawful or unplanned use, access, modification, or destruction,1 ismore critical today than ever. Due to the growing numbers of datanetworks, digital applications, and mobile users—and the increasednumber and sophistication of cyberattacks—ongoing vigilance isneeded to protect private and proprietary information.As the United States increasingly relies on networks to collect,process, store, and transmit confidential data, the work ofcybersecurity professionals is essential to protecting the onlineactivities of individuals, organizations, and communities.2 TheInternet of Things (IoT)—the ability of everyday objects totransmit data through a network—increases the vulnerability ofvirtually all aspects of life to cyber threats. In IoT, embedded chips inall manner of “smart” objects—an automotive sensor, insulin pump,jet engine, or oil drill—become the potential “victims” of breaches oroutages. Without adequate security, data breaches can result in outcomes ranging from minor inconveniences to personal, corporate, orgovernment disasters with devastating consequences for individuals,enterprises, regional populations, or the global economy.Recognizing that no organization is immune to cybersecuritythreats, company leaders are increasingly making cybersecurity anoperational priority. After the widely reported cyberattacks on leadingretailers (Target and Neiman Marcus), financial services companies(JPMorgan Chase), and technology-based companies (eBay, Adobe,and Snapchat),3 business leaders agree that boosting cybersecuritymeasures is a critical investment. Wade Baker, principal author ofVerizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report series, cautions: “Afteranalyzing 10 years of data, we realize most organizations cannot keepup with cybercrime—and the bad guys are winning.” 4The types of cyberattacks—and their causes—may vary. Onereport identified seven top causes of major cybersecurity breaches,shown in Figure 1 on page 4.5 A data breach analysis of more than63,000 cybersecurity incidents across 50 companies in 2013revealed that 94% of data breaches fell into one of nine categories,illustrated in Figure 2 on page 4.6200,000 Malware AttacksPer year in 2006Per day in 2013Source: “The Top Seven Causes of Major Security Breaches,” Kaseya, accessed June 24,2014, op-seven-causes-of-majorsecurity-breaches. 46 BillionAnnual global spending on cybersecurity20% IncreaseIn cybersecurity breaches per year30% IncreaseIn annual cost of cybersecurity breachesSource: Stuart Corner, “Billions Spent on Cyber Security and Much of It ‘Wasted,’”The Sydney Morning Herald, April 3, 2014, 0403-zqprb.html.University of Maryland University College, “Cybersecurity,” 2014, ity-basics.cfm.U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Cybersecurity Overview,” accessed June 24, 2014, http://www.dhs.gov/cybersecurity-overview.Yoav Leitersdorf and Ofer Schreiber, “Is a Cybersecurity Bubble Brewing?” Fortune, June 17, 2014, ubble-brewing/.4“Verizon 2014 Data Breach Investigations Report Identifies More Focused, Effective Way to Fight Cyberthreats,” Verizon Corporate (press release), April 23, 2014, 5“The Top Seven Causes of Major Security Breaches,” Kaseya, accessed June 24, 2014, , 2014 Data Breach Investigations Report, 2014, http://www.verizonenterprise.com/DBIR/2014/?gclid CO6dqdqPk78CFdBi7AodYz8Amw.1233

63%CISO 4.7 445BillionBillionCIO63 % of U.S. Federal CIOs (ChiefInformation Officers) and CISOs(Chief Information Security Officers) sayimproving cybersecurityis a top priorityProposed annualAnnual costU.S. Department of Defenseof computer- and network-basedcrimes worldwidespending on cyber activitiesSources: Homeland Security News Wire, “Improving Cybersecurity Top Priority: Federal CIOs, CISOs,” June 12, 2014, cisos. Andy Sullivan, “Obama Budget Makes Cybersecurity a Growing U.S. Priority,” Reuters, April 10, 2013, iscal-cybersecurity-idUSBRE93913S20130411. Tom Risen, “Study: Hackers Cost More Than 445 Billion Annually,” U.S. News & World Report, June 9,2014, ure 1. Most major cybersecurity breaches have oneof seven causes.4.55% CEO/president/general manager/owner/principal/Naive8.07%end userspartnerand disgruntled Chief securityemployeesofficerUsers notperimeter NoVicePresidentkeeping up withprotect toDirectornew tactics28.57% Manager Supervisor of42.44%security personnel11.18%5.18%Top 7 causesUnderof cybersecurityMobileNote. Total who responded to the question 483 (100%)estimatingdevices asbreachescyberideal entrycriminalspointsFigure 2. Ninety-four percent of cybersecurity breachesin 2013 fell into these nine categories.4.55% CEO/president/general enial-of Chief securityOtherserviceWeb appofficerattacksattacks VicePresidentPhysical Directortheft/loss28.57% ManagerCyber Supervisor ofespionage42.44%security ategories ofcybersecuritybreachesNote. Total who responded to the question 483 (100%)CrimewareLack of a layereddefenseSource: Kaseya.4Loss of aymentcardskimmersSource: Verizon, based on reports from 50 companies.

Career Opportunities in theCybersecurity IndustryWith the urgent need to build a national workforce of well-qualifiedcybersecurity professionals, the security industry offers substantialemployment opportunities. Accounting for approximately 10%of all IT occupations in the United States, cybersecurity-relatedpositions are growing faster than all IT jobs.7 Postings grew 74% from2007 to 2013, with 209,749 postings in 2013.8While cybersecurity job openings take 24% longer to fill than all ITopenings, and 36% longer to fill than all vacancies (regardless ofindustry), U.S. employers pay qualified candidates a premium forcybersecurity jobs—an average of 93,028 annually, or over 15,000more than other IT jobs overall.9 As an example of the scarcity of qualified candidates: In 2013, U.S. employers posted 50,000 new jobs requiring a Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP)credential—but there are only 60,000 total existing CISSP holders.10U.S. Cybersecurity Job Postings209,749Cybersecurity-relatedjob postings in 2013U.S. cybersecurity jobs account for 10% of all IT jobsand take 24%50,000 U.S. jobsrequesting CISSPVS.60,000 total74%100%longer to fill than all IT jobs.CISSP holdersIncrease75%50%25%f2XastehrtanalTlIjobsU.S. cybersecurity salaries are 15,0000%2007 08091011higher on average than IT jobs overall.12 2013Source: Burning Glass.Burning Glass Technologies, “The Growth of Cybersecurity Jobs,” 2014, y/.Ibid.Ibid.10Ibid.7895

Defining a Common Set of CybersecurityProfessional CompetenciesWith the rising demand for qualified cybersecurity talent, industryleaders are increasingly calling for a common definition of the scopeof work that cybersecurity covers—and agreed-upon competenciesthat cybersecurity professionals must demonstrate.11 Defining astandard set of industry-aligned professional competencies can helpin educating, recruiting, developing, and retaining the caliber of talentthat the industry needs.Figure 3. Categories of the National Initiativefor Cybersecurity Education (NICE) NationalCybersecurity Workforce Framework.4.55% CEO/president/PROVISION Specialtyareas responsible11.18% SECURELY5.18%generalmanager/for conceptualizing, designing, andbuildingsecure ITowner/principal/8.07% for somesystems (i.e., responsibleaspect of systemspartnerdevelopment).Striving toward common definitions and competencies, theNational Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE)developed the National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework, and theU. S. Department of Labor (DOL) developed the CybersecurityIndustry Competency Model.The NICE Framework describes cybersecurity work across industries,organizations, and job types, and consists of seven categories, with31 specialty areas.12 For each specialty area, the Framework identifiesthe job tasks, knowledge, skills, and abilities that individuals mustdemonstrate to perform effectively. The seven categories of the NICEFramework are shown in Figure 3. The categories represent typical jobduties performed by cybersecurity professionals. Chief securityofficerOPERATE AND MAINTAIN Specialtyareas VicePresident andresponsible for providing support,administration,maintenance necessary to ensureeffective Director28.57%and efficient IT systemperformanceand security. Manager SupervisorofPROTECT AND DEFEND Specialtyareas responsiblesecurity personnelfor identification, analysis, and mitigationof threatsinternalto IT systemsor networks.Note. Total whorespondedto the question 483 (100%)42.44%INVESTIGATE Specialty areas responsible forinvestigation of cyber events and/or crimes of IT systems, networks, and digital evidence.COLLECT AND OPERATE Specialty areas responsiblefor specialized denial and deception operations andcollection of cybersecurity information that may beused to develop intelligence.ANALYZE Specialty areas responsible for highlyspecialized review and evaluation of incomingcybersecurity information to determine itsusefulness for intelligence.OVERSIGHT AND DEVELOPMENT Specialty areasproviding leadership, management, direction, and/or development and advocacy so that individuals andorganizations may effectively conductcybersecurity work.Adapted from NICE, The National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework.A competency is defined as a group of related skills and abilities that influence a major job function, indicate successful job performance, are measurable against standards, andare subject to improvement through training and experience. See CareerOneStop, “Develop a Competency Model,” 2014, uide competency.aspx.12National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education, The National Cybersecurity Workforce Framework, last modified February 6, 2013, ecurity workforce framework 03 2013 version1 0 interactive.pdf.116

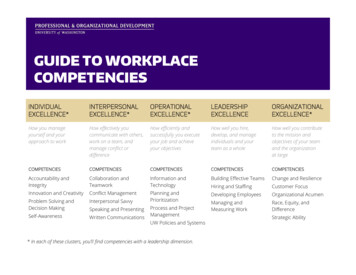

Defining a Common Set of CybersecurityProfessional Competencies (cont.)Incorporating the competencies of the NICE Framework, theDOL’s Cybersecurity Indust

Competency Model—have been developed to standardize professional requirements. The NICE Framework defines seven categories of typical job duties, covering cybersecurity work in 31 specialty areas across industries and job types. The DOL’s model expands this Framework to i