Transcription

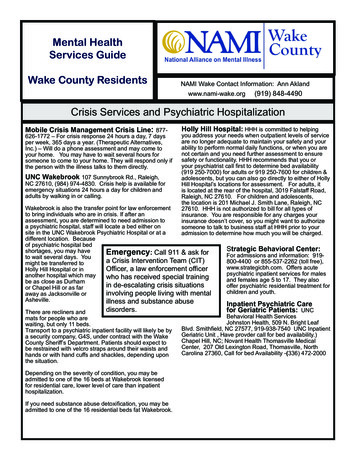

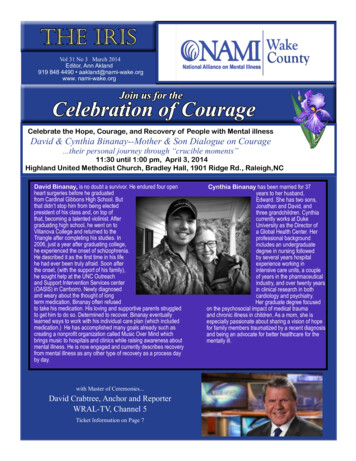

The IrisVol 31 No 3 March 2014Editor, Ann Akland919 848 4490 aakland@nami-wake.orgwww. nami-wake.orgCelebration of CourageCelebrate the Hope, Courage, and Recovery of People with Mental illnessDavid & Cynthia Binanay--Mother & Son Dialogue on Courage.their personal journey through “crucible moments”11:30 until 1:00 pm, April 3, 2014Highland United Methodist Church, Bradley Hall, 1901 Ridge Rd., Raleigh,NCDavid Binanay, is no doubt a survivor. He endured four openheart surgeries before he graduatedfrom Cardinal Gibbons High School. Butthat didn’t stop him from being electedpresident of his class and, on top ofthat, becoming a talented violinist. Aftergraduating high school, he went on toVillanova College and returned to theTriangle after completing his studies. In2006, just a year after graduating college,he experienced the onset of schizophrenia.He described it as the first time in his lifehe had ever been truly afraid. Soon afterthe onset, (with the support of his family),he sought help at the UNC Outreachand Support Intervention Services center(OASIS) in Carrborro. Newly diagnosedand weary about the thought of longterm medication, Binanay often refusedto take his medication. His loving and supportive parents struggledto get him to do so. Determined to recover, Binanay eventuallylearned ways to work with his individual care plan (which includedmedication.) He has accomplished many goals already such ascreating a nonprofit organization called Music Over Mind whichbrings music to hospitals and clinics while raising awareness aboutmental illness. He is now engaged and currently describes recoveryfrom mental illness as any other type of recovery as a process dayby day.with Master of Ceremonies.David Crabtree, Anchor and ReporterWRAL-TV, Channel 5Ticket Information on Page 7Cynthia Binanay has been married for 37years to her husband,Edward. She has two sons,Jonathan and David, andthree grandchildren. Cynthiacurrently works at DukeUniversity as the Director ofa Global Health Center. Herprofessional backgroundincludes an undergraduatedegree in nursing followedby several years hospitalexperience working inintensive care units, a coupleof years in the pharmaceuticalindustry, and over twenty yearsin clinical research in bothcardiology and psychiatry.Her graduate degree focusedon the psychosocial impact of medical traumaand chronic illness in children. As a mom, she isespecially passionate about sharing a vision of hopefor family members traumatized by a recent diagnosisand being an advocate for better healthcare for thementally ill.

The IrisNAMI Wake CountyNAMI WakeBoard of Directors 2014NAMEOfficeGerry AklandPresidentAnn AklandAdvocacyEllen Betts ClemmerSecretaryDorothy CliftAt LargeMary Ann CrandellAt LargeJudith DeHavillandAt LargeCrystal Farrowex officioTom HadleyMembership SecretaryMarc JacquesConsumer ChairLouise JordanAt LargeMary O’NealAt LargePaul RobitailleTreasurerWilliam StanleyAt LargeChristine TaylorAt LargeAnju VermaAt LargeSarah WeathersbyAt LargePage 2Five years have passed.State Mental Health System ProblemsWorse than EverFrom the President’s Deskby Gerry AklandNAMI Wake County has been documenting the many problems for peoplewith mental illness for over 5 years. For example, our first publication wasreleased October 7, 2008, titled “Indicators of the Impact of North Carolina’s“Mental Health Reform” on People with Severe Mental Illness.” (http://www.nami-wake.org/files/NAMI Wake Indicators Report.pdf) Since these 5 yearshave spanned a major shift in our political leadership, it might be interestingto review the recommendations we provided to the State and see if there hasbeen any progress. Below is a status report of 2 of the 15 recommendationsmade in 2008.Recommendation 1: Create a comprehensive and integrated statesystem for tracking and reporting data. This system would integrate datafrom public health (morbidity, mortality, and suicide), data from our prisonand jails, and data from financial management (budget trends, allocations,reimbursements for every type of funds and service).Status: A comprehensive, integrated state system for tracking andreporting data does not exist. There is a state work group addressing a portion of the need, but thus far has not tackled the “stovepipe” problem of different systems, including jail and involuntary commitment data, not to mention the need to look at outcomes ofservice, rather than performance measures. The lack of a comprehensive, integrated state system for tracking and reporting datais a major failure of NC DHHS in general and the Division of Mental Health, Substance Abuse and Developmental Disabilities tounderstand the system that they are responsible for managing. How can one make good decisions without data?Recommendation 2: Increase the number of psychiatric hospital beds. In the past 50 years, the number of public psychiatricbeds in the US has been reduced by 95%. The Treatment Advocacy Center (TAC) presents a consensus opinion of experts thatstates need a minimum of 50 public beds for every 100,000 people (Torrey, 2008). The report describes NC as having a severeshortage with over 1,000 beds needed.Status: Between 1992 and 2010, the state closed 1,879 psychiatric beds, in addition to significant losses in communitypsychiatric beds. In the FY 08/09 mental health budget, the Secretary of DHHS and the NC General assembly recognized thecontinuing loss of community beds as a major need and provided 8M for contracts with local community hospitals. The moneywas provided to hospitals with existing psychiatric beds, in an effort to slow down the reduction of community psychiatric beds. Thishas resulted in a modest ( 8%) increase of community beds, from 1,744 in 2010 to 1878 today. Instead of adding significantly morecommunity and public psychiatric beds, funding community beds is continuing. For example, the state provided 38M In the 201314 funding for community psychiatric beds which funds about 200 community beds. Today the total number of beds in NC is 2,770(2,399 adult beds), about half the number estimated by TAC. It is interesting to point out that included in this total are 812 stateinpatient adult beds and 80 state inpatient child beds. In 2008, the state beds served 16,789 people. In 2013, only 3,964 peoplewere served, a reduction of over 75%. Where do the people go who need crisis services?Ask the Emergency Departments across the state. Or ask those in charge of managing our jails. For example, the number of EDadmissions with primary mental health diagnosis has increased by 30% since 2009. The numbers do not convey the true costof the failure of mental health reform. Ask anyone who has suffered the indignity and loss of self-respect as they wait for a bed

NAMI Wake CountyThe IrisPage 3continued from page 2somewhere in the state where they can begin to receive treatment, just to get through their crisis. Or the cost of riding in a sheriff’scar bound in handcuffs and shackles.There is some good news to report for Wake County. Since 2008, the Wake County Commissioners have approved additionalfunding for mental health, have built a new facility (WakeBrook), and more recently, a new small (16 bed) inpatient unit has beenestablished and is operating under UNC Healthcare. In addition, a new private hospital, Strategic Behavioral Health, has beenbuilt in Garner with 20 Child/Adolescent Inpatient Psychiatric (acute) beds. And a 13 bed geriatric psychiatry unit was added inFranklin County. Addition of these 3 facilities should greatly reduce the waiting time for these hard to place individuals in needof specialized care. However, the DHHS has estimated that Wake County needs 44 additional adult beds by 2016 (presented toLOC committee, Feb. 2014).Other Factors: Within our 2008 report recommendations for promoting best practice services and increased funding forservices were also included. With regards to the first, best practice services, the number of people served in Assertive CommunityTreatment Teams (ACTT) and Community Support Teams (CST) has gone down from 4194 ACTT and 6,136 CST in JanuaryMarch 2011, to 3,396 ACTT and 2202 CST in October-December, 2012. This represents a drop of 19% and 64% respectively inthe number of persons served. These two services provide intensive, wrap-around services to help prevent crises and need forhospitalization. In addition, funding was cut for mental health services in 2013.Is it any wonder that mental health reform is such a failure?Construction of New Children’s Psychiatric HospitalRALEIGH – In response to a growing need forinpatient psychiatric beds, Holly Hill Hospitalrecently broke ground on a children’s psychiatrichospital for North Carolina. The new facility willbe located less than a mile from the current HollyHill Hospital in Raleigh and will be a center ofexcellence for child and adolescent mental healthtreatment.Designed to incorporate the natural elements ofthe area, the 53,000 square foot hospital will provide a soothing and comfortable treatment environment.The facility grounds boast four outdoor play areas including a traditional playground, two walking trailsand a basketball court. There are also open-air places for dining and for family visitation. Inside, a halfcourt gymnasium, art therapy room, classroom and game room provide opportunities for exercise andnon-traditional therapy. Each of the hospital units also features a true comfort area to allow a full sensoryapproach to treatment. The specially designed admission and visitation areas and the planned capabilitiesfor telehealth, will also allow for increased family involvement and therapy.Slated to open in the fall of 2014, the hospital will offer 60 acute psychiatric beds for children andadolescents. In the following months, the children’s hospital will expand to full capacity at 80 beds. Atopening, Holly Hill will move all of its current children and adolescents services to the new hospital, openingan additional 37 adult beds at its existing location.For more information on Holly Hill Hospital, please visit www.HollyHillHospital.com.

NAMI Wake CountyThe IrisPage 4Crisis pointMentally ill and incarcerated in the Rutherford County jailReprinted from article in the Daily Courier, Forest City, NCMar. 02, 2014 @ 05:00 8019/CrisispointSTEPHANIE JANARDEditor’s note: Due to the sensitive topic of this story, “Kim” is notthe real name of the subject.Like other parents before her, Kim confused the onset of herson’s mental illness with normal teenage behavior. “He wouldisolate himself in his room for days at a time,” the RutherfordCounty native recalled. “I thought maybe he was just being atypical teenager who didn’t want to see his parents.”According to Kim, it turned out her son was hallucinating. Andhearing voices. It would take years, she said, before he wasfinally diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, one of the moredifficult mental illnesses to correctly diagnose.It’s also one of the hardest to have. People who suffer fromit can experience schizophrenic hallucinations and delusionswhile swinging from one extreme mood to another. Withouttreatment, it can be impossible to hold down a job or evenmaintain a stable relationship.Her son’s own diagnosis, Kim said, marked his tenuous returnto sanity. Now that his condition had been identified, doctorscould prescribe him a specific plan of treatment, which includedanti-psychotic medication. The journey back to mental stabilitywasn’t without detours, however.Her son went on and off his medication, Kim said, and whenhe was off, trouble usually followed. But once back on, hecould go long stretches without hospitalizations; eventually,a full two years. Towards the end of 2012, her son startedto talk about gaining more independence. Maybe even gethis own apartment. According to Kim, around this same timehe also started seeing a new doctor with a behavioral healthorganization in Forest City.Unlike previous doctors who had treated her son, she said, thisone took a dim view of medication – and told her son he mightbe better off without it. Kim said this advice frightened her somuch she went to see the doctor herself. “I told him he didn’tknow my son like I did. I said that he could get real ‘out there’when he was off his medication,” she recalled.Nor would the organization confirm or deny if patients withsevere mental illnesses are indeed being encouraged toeliminate medication from their treatment plans - and if so, whatsteps are taken to mitigate the risks of withdrawal and the returnof mental illness symptoms.While she acknowledged that HIPAA privacy laws limit providersfrom discussing their patients, Kim said the doctor didn’t seemworried by her concerns, or even much interested in her son’smedical records that she’d brought with her. “I asked his officeto make copies of them anyway. And I waited there until theydid,” Kim said.A parent’s plea to be heardKim ultimately ended up filing a complaint about the doctorwith the now-defunct Western Highlands Network, the quasistate agency with regional oversight of publicly-funded mentalhealth services. Since acting on his doctor’s suggestion thathe might be better off without medication, Kim wrote to WesternHighlands, her son had been evicted from his apartment,banned from an area grocery store, repeatedly hospitalized,and arrested twice - the first time for assaulting a male nurseat Rutherford Hospital; the last for breaking and entering into astranger’s home.At the peak of all this chaos she’d attempted to get him helpby calling Crisis Mobile, Kim continued. The response from thecommunity service tasked with de-escalating emergency mentalcrisis situations was that no one could come out unless her sonrequested the help himself.“A person with mental illness and that is off their medication isalmost like a person with Alzheimer’s,” Kim wrote. “They don’trealize they need help. They don’t even know they’re sick.”Western Highlands responded with a form letter that advisedKim that inquiries had been made and any concerns deemednecessary relayed to the provider. Although the letter providedno insight into what those concerns might be, or what specificactions, if any, would be taken by the provider, the letterconcluded by telling Kim she had 15 working days to appeal.“Every which way I turned was a roadblock,” Kim said. Monthslater, her son remained incarcerated at the Rutherford CountyDetention Center.When contacted by the paper, both the doctor and thebehavioral health organization declined to be interviewed.Continued on page 5

NAMI Wake CountyThe IrisContinued from page 4Lt. Greg Cochran has personally witnessed an inmate switchback and forth between three personalities in the span of15 minutes. “The first was a God-fearing family man, asrespectable as anyone you’d meet in the community. And thenright in the middle of our conversation he told me he was goingto kill me,” the Rutherford County Detention Center administratorrecalled. “He just spit out the words, with venom. And then justas suddenly he started talking about how someone was going tokill him.”It was a conversation that would leave most people shaken.For Cochran and his staff, it’s just another day on the job. “Wedeal with mental health issues every hour of every day,” hesaid. He estimated that approximately 60 percent of inmates atthe Detention Center are on some sort of mental illness-relatedmedication, although rarely when they first arrive. In fact, formany of the inmates, going off their medication is what triggeredthe events that landed them in jail.“That was the case with the gentleman with the threepersonalities,” Cochran noted. Jail, he added, is not the rightplace for many of these inmates to be. “At the most basic level,they need someone to talk to. I’ve watched inmates stay postedat their bars waiting for a guard to pass by, just to have a coupleof minutes of conversation with someone,” he said. Whenasked if doctors sometimes call or visit the jail out of concernfor mentally ill inmates who were previously under their care,Cochran couldn’t recall a single incident of this ever happening.The jail, however, does attempt to stabilize mentally ill inmates.A mental health screening is performed at each new intake, andthe jail nurse will initiate contact with providers to obtain inmates’medication history and other information.The county also contracts with a doctor who Cochran saidspends up to half of his time on mental illness-related issues.While the detention center did not provide The Daily Courierwith an estimate of what these services cost, similar contractsin other counties run in the hundreds of thousands of dollars peryear. Cochran did provide estimates for the Rutherford CountyDetention Center’s mental illness medication costs, whichCochran said run annually about 14,000.As for what happens to mentally ill inmates after release, few ifany processes are in place to keep them from coming right back.Rutherford County does not have a special mental health court,Page 5for example, that could divert more mentally ill offenders tocourt-ordered treatment instead of jail. Even if it did, a shortageof residential facilities, including state psychiatric hospital beds,is another obstacle. For Kim, it is a particularly bitter pill that herson was waiting for a bed to open up at the state psychiatrichospital in Broughton when he assaulted the male nurse atRutherford Hospital.There is also the matter of an inmate’s ability to pay formedication after release. A large number of the mentally ill relyon Social Security Disability Income and Medicaid, both of whichare automatically suspended while a recipient is incarceratedand won’t resume until official notification from the jail of therecipient’s release. Obviously, the sooner that jails send thisinformation, the less time inmates have to wait to receivecoverage for medication and other treatment expenses. ButCochran said that the detention center only sends out thesenotifications upon request.Finally, the system is simply not structured in a way thatmotivates providers to keep track of clients who stop services- and few appear to take the initiative to do so anyway. Kimfigured her son has been treated by five or six different doctorsin the close to 10 years he’s struggled with mental illness. Afterhis incarceration this past fall, she left messages with several ofthem. None, she said, ever returned her calls.Meanwhile, her son’s court date was repeatedly pushed backuntil a mental health evaluation could be scheduled. When onefinally took place, Kim was told he had been found mentallyincompetent to stand trial at that time. However, he remainedincarcerated for several more months, until finally, he wasassigned another court date on Jan 30.On that morning, Kim watched from her seat in the gallery as herson was led handcuffed into a Rutherford County courtroom. Hewas the thinnest she’d ever seen him. While officials conferredover his case, Kim strained forward in an attempt to hear whatwas being said. Eventually she was informed that after almostsix months of incarceration in the county jail, her son was finallybeing remanded to treatment at Broughton.To reach the writer of this story, contact Stephanie Janard atsjanard@msn.comThe above article is about a family living with serious mental illness in the western part of NorthCarolina. Even so, it is the same situation here in Wake County. With our population nearing 1Mresidents, the Wake County jail is the largest institution housing people with mental illness in theentire state. The same problems and issues described by the Rutherford County Sheriff exist in Wake County. Withthe shortage of psychiatric beds, fewer people are being deemed to be ill enough to warrant commitment. Often, theyare released from the Emergency Room or Crisis Center with or without an outpatient appointment with a mental healthprovider. But, how many actually fol

funding for mental health, have built a new facility (WakeBrook), and more recently, a new small (16 bed) inpatient unit has been established and is operating under UNC Healthcare. In addition, a new private hospital, Strategic Behavioral Health, has been built in Garner with 20 Child/Adoles