Transcription

And Then There Were None? Measuring theSuccess of Commercial Language CoursesJeff McQuillanIntroductionSelf-study language courses have a long historyin L2 education, but they have failed to capturethe interest of researchers in applied linguistics(see Krashen, 1991, and Krashen & Kiss, 1996).These courses have been produced by severalcompanies, including Berlitz, Pimsleur, LivingLanguage, the Rosetta Stone and more recently,by independent producers via podcasts andwebsites (McQuillan, 2006). Some of thecourses are limited to books and CDs, whileothers include an internet component or aredelivered exclusively online. Lessons tend tofocus on expressions related to travel or dailyconversation, and are often guided by agrammatical syllabus.Most companies that produce these courseshave not released sales figures, but if the salesrank on the e-commerce site Amazon.com is avalid indication of popularity, at least some ofthe courses are among the most populareducational items sold. At the time this articlewas written (summer, 2018), for example, thebook Easy Spanish Step by Step by Bregsteinhad an Amazon.com sales rank of 978, makingit one of the top 1,000 books sold on the site. Bycomparison, books written by two recent U.S.presidential candidates Trump and Clinton hadsales ranks of 8,548 and 3,990 respectively.While popular, few of these courses have beenevaluated for their effectiveness in promotingforeign language fluency. The only exception isHarry Winitz’s Learnables (2003), which hasbeen evaluated numerous times (Winitz & Reed,1973; Winitz, 1981, 1996).Language and Language TeachingA rough measure of gauging the success of aself-study course is to look at perseverance instudy. Do the students manage to reach theintermediate and advanced levels of the course?One of the earliest studies of persistence inforeign language study was conducted byDupuy and Krashen (1998). The researcherscollected background data and observed theclassroom behaviour of a group of intermediateand advanced level college students. Their maininterest was to document the characteristics ofthose who had “survived” the lower-levelcourses, and had advanced to the upper-divisionclasses. They concluded that only a very smallpercentage of lower-division students did in factreach what they refer to as the “PromisedLand” of upper-division courses. Those who didadvance in their studies had extensive exposureto the language outside of the classroom: 84.5per cent had participated in a study abroadprogram.Data from other sources confirm Dupuy andKrashen’s findings on the high attrition rate inlanguage courses. Table 1 summarizes data onforeign language course enrollment in highschool over a period spanning 75 years.Coleman (1930) reported on statewide highschool foreign language enrollments by level,for an unnamed northeastern U.S. state in 1925.Draper & Hicks (2002) provide more recentdata from the year 2000, covering all 50 states.In addition to the raw figures, I have calculatedthe percentage of the students who “survived”each passing year of study, dividing the numberof students at each course level by the totalbeginning (Level I) enrollment.Volume 8 Number 1 Issue 15 January 201943

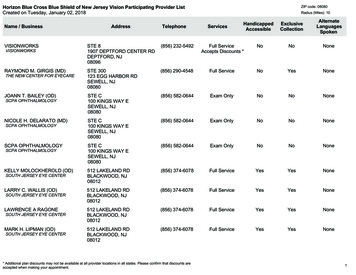

Table 1Foreign Language Enrollments by Level in High School in 1925 (1 State) and 2000 (50 states)Note. For the year 2000, the data includes any higher levels (e.g. Spanish V or VI) plus Advanced Placementcourses. Data from Coleman (1930) and Draper & Hicks (2002)Note that there are similar declines from LevelI (freshman) to Level IV (senior) in both setsof data. Also, the attrition rate is particularlysteep after the second year. In 1925, 95.5 percent of students had dropped out of study beforereaching Level IV. In 2000, it was marginallybetter at 82 per cent, but still high.Yet, a significant number of students also saidthey genuinely wanted to learn the language.More than half of the students said they were“interested in learning to read and write” (meanscore of 1.69), and nearly as many said theyhad a “particular interest in Spanish/Frenchculture” (mean score of 1.59).The situation does not improve at the collegelevel. Furman, Goldbert, and Lusin (2007), reportthat of the 1,536,614 undergraduates enrolledin the top 15 foreign languages in the U.S.colleges in 2006, only 17 per cent were enrolledin upper-division courses. This attrition rate issimilar to what we find at the high school level.There is little data available on the motivationsof independent adult second language studentswho pursue study outside the formal classroom.Presumably, some students have short-termobjectives such as travel to another country, andseek only a very basic level of proficiency.However, as in the case of Ramage’s (1990)subjects, many adults would no doubt like toreach higher levels of competency in thelanguage.There are probably a variety of reasons as towhy students fail to advance in formal languagestudy. Many students take these courses as arequirement for graduation and therefore stopat the lowest class necessary to reach that goal.Ramage (1990) conducted a survey across agroup of high school students (N 138). He askedthem to indicate their agreement to statementsrelated to their reasons for foreign languagestudy on a 3-point Likert scale, in which “3”meant the subject agreed. A clear majority ofthe students indicated that one of the reasonsthey were taking the class was to fulfill agraduation requirement (mean score of 2.59).Language and Language TeachingAlthough there are few independent evaluationsof commercial language programs, we do havesome evidence on persistence rates within andacross language course levels. I will summarizethe results from three such studies: McQuillan(2008), who used unobtrusive or “non-reactive”methods of examining a set of course booksused by adult acquirers; Nielson (2011), whoconducted a quasi-experimental study of a groupof mostly government workers who were givenaccess to two commercial language courses;Volume 8 Number 1 Issue 15 January 201944

and Ridgeway, Mozer, and Bowles (2017), whoreported attrition rates based on more than125,000 users of one of the largest self-studylanguage courses, Rosetta Stone.McQuillan (2008): Use of Library SelfStudy BooksMcQuillan (2008) attempted to gauge thepersistence of independent language studentswho used print versions of self-study languagebooks that they borrowed from a large, urbanlibrary system. He created an “unobtrusivemeasure” (Webb, 1966), called the “Wear andTear” Index, to measure roughly how much ofa book was read by the patrons. Similar indiceshave been used by previous researchers suchas Debois (1963) and Moestller (1955) (as citedin Webb, 1966), to determine which parts of alibrary reference book were most frequentlyconsulted, and which newspapersadvertisements were seen by readers.These indices often use a combination ofmarkers indicating both “erosion” (physicaldegradation, such as tears in a book page orbent back page corners) and “accretion” (addeddirt, dust, and smudges). McQuillan’s Wear andTear Index (2008), included both types ofmeasures:1. The separation of the pages close to thebinding.2. Fingerprints or smudges on the pages or thecorners.3. Worn or wrinkled corners likely caused bypage turning.He examined a set of 10 self-study languagebooks, representing six different languages. Herecorded the highest page number in the bookthat showed some evidence of one or moremeasures in the Wear and Tear Index. To ensurethat there had been a sufficient amount of patronuse of the books, only those books that had beenin circulation for at least one year wereexamined. Table 2 (adapted from McQuillan’sTable 1) reports the name of the book, the lastpage used, the total number of pages, and theTable 2Use of Commercial Language Courses by Library PatronsNote. * excluding glossaries or bilingual dictionaries at the end of the volume; adapted from McQuillan(2008)Language and Language TeachingVolume 8 Number 1 Issue 15 January 201945

estimated percentage of use and progress in thecourse. Note that in no case did the averagepercentage of course book use exceed 27 percent, with an average of 16.8 per cent read.McQuillan’s study may actually haveunderstated the dropout rates, since he measuredonly the highest page number showing evidenceof some use by patrons. This is not the same asthe average use of the course book. One ortwo outliers could have used the book moreextensively, skewing his estimates. For a moreaccurate measure of persistence, we need tomeasure course use more directly, as was donein the next two studies.Nielson (2011): Users of Rosetta Stone andTell Me More SoftwareNielson (2011) looked at two groups of U.S.government employees working in agencies thatprovide self-study language training. TheRosetta Stone group (N 150) consisted ofemployees from a number of different agencies.All the employees were “absolute beginners”in the language they had chosen to study(Arabic, Chinese, or Spanish), i.e. they had noprevious coursework in the language. The TellMe More group (N 176) consisted of studentsemployed by the U.S. Coast Guard. The TellMe More group only studied Spanish, but unlikethe Rosetta Stone group, the students were atvarious proficiency levels. All subjects werevolunteers who had sought to participate in thestudy, and Tell Me More students had been giventime off their regular duties to do so (up to threehours per week).The Rosetta Stone group used a popular internetbased software program designed for self-studyof languages. While the program is available onCD-ROM, participants could only access anonline version, as per the procedure of theparticipating government agencies. The Tell MeMore group used Aurolog’s Tell Me Moresoftware, also available only online.Language and Language TeachingRosetta Stone students agreed to use the coursematerials online for 10 hours per week for 20weeks, giving them time to complete therecommended 200 hours for Level I of thecourseware. Tell Me More students agreed touse the courseware for at least five hours perweek for 26 weeks.To measure the program’s effectiveness,Rosetta Stone students were given proficiencyinterviews over the phone, in which they wereasked to identify and describe pictures similarto the ones that appeared in their course. Thetests were administered after the completion ofeach 50-hour segment of the 200-hour longstudy period. They were also given an ACTFLOral Proficiency Interview (OPI) as an exit test.The Tell Me More students took the program’splacement and exit tests, as well as the Versantfor Spanish oral proficiency assessment, whichcorrelates highly with the OPI exam (Fox &Fraser, 2009). Tell Me More students whoalready knew some Spanish were given theVersant as a pre-test, and all students were tobe given it as a post-test. Students in both groupswere asked to keep a “learner log” to track howmuch time they had studied the materials.Although Nielson’s (2011) intention was tomeasure the effectiveness of the programs inpromoting language acquisition, she found that“the most striking finding [for both groups] wassevere attrition in participation” (p. 116). I havesummarized the attrition data from her study inTable 3. In both the Rosetta Stone group andthe Tell Me More group, there were steepdropout rates, as indicated by the “percentageof survivors” column (the number of studentsreaching that level divided by the total numberof students enrolled in the program at theoutset). Nielson used different categories toreport the data for the Rosetta Stone and TellMe More groups (as noted in Activity columnof Table 3). For the Rosetta Stone results,Volume 8 Number 1 Issue 15 January 201946

Nielsen used signing into an online account asthe third milestone, whereas for Tell Me Morethe third milestone was “Used TMM for 5hours.” Other differences are noted in column 1of Table 3. Despite these differences, the patternis very clear.Of the students who signed up for the RosettaStone courses, only 21 per cent completed evenTable 3Attrition in Participation Using the Rosetta Stone and Tell Me More Software ProgramsNote. From Nielson (2011) Tables 1 and 2, pp. 116-117* % Survivors Number of students reaching level/Total number of student who signed up for the course10 hours of the 200-hour course (5 per cent ofthe total). Only one of the 150 volunteers madeit to the end. For the Tell Me More course, lessthan 10 per cent made it to the 10-hour mark(13 per cent of the way through the course),with a mere four completing the finalassessment. The attrition rate from beginningto end was 99.4 per cent for Rosetta Stone,and 97.8 per cent for Tell Me More.Although the language proficiency assessmentswere taken by only a fraction of the participants,Nielson found that more hours spent on thecourse did produce better scores on the interimassessments. She concluded, however, that thenumber of subjects who took the exams wasLanguage and Language Teachingtoo small to be of much use in evaluating theeffectiveness of the programs.Nielson noted that not all of the attrition couldbe blamed on the programs. A significantpercentage of the students apparently had avariety of technical problems with the software(browser plugins that would not load, systemcrashes, etc.). Some of the participants reporteddropping out as they were assigned overseasduring the course of the study, others cited nothaving enough time, or a change in their worksituations. Most of them however, did notprovide reasons for dropping out. In addition tothe technological problems, there were alsocomplaints about the content of the coursesVolume 8 Number 1 Issue 15 January 201947

themselves. Nielson (2001) concluded that thehigh dropout rates for the software programsmeant that such self-study products are “unlikelyto work by themselves”, without proper support(p. 125).Ridgeway, Mozer, & Bowles (2016):Institutional Use of Rosetta StoneRidgeway, Mozer, and Bowles (2016) analyzeda large set of data (N 125,112) gleaned fromstudents of the Latin American Spanish onlinecourse offered by Rosetta Stone. Rosetta Stoneitself supplied its internal tracking data to theresearchers; this data included “institutional”clients only (universities, governments andprivate companies). Ridgeway and colleagueslooked at student enrollment and completion ofthe Level I, II, and III courses (beginning toadvanced Spanish) between 2008 and 2014.Each level of the courses had 16 units, with areview/assessment activity at the end of the unit.Ridgeway et al. calculated the completion ratesfor each unit across the three levels, reportingthe results by unit.I summarized their findings by level, includingthe first unit, the 8th unit (mid-point), and the16th and final unit, in Table 4. I estimated theapproximate number of students on each levelfrom Ridgeway et al.’s (2016) Figure 2 bar chart(p. 931). The data was reported by theresearchers on a logarithmic scale, so myestimates are only approximate. I also calculatedthe “per cent of survivors” using the sameapproach as in my discussion on Nielson (2011)(number of students reaching that level dividedby total enrollment in Unit 1).Table 4Attrition in Participation for Institutions Using Rosetta StoneNote. Data from Ridgeway et al. (2016).The sharp decline in course completion is evidentfor all three levels. Dropout rates were highestin Level I, where only 29 per cent of thestudents completed the mid-point assessment,and just under 6 per cent made it to the end ofthe course. This is higher than Nielson’s (2011)findings, although her data came from a small,more restricted sample. Level II students faredthe best, with about one-half of them making itto the 8th unit, and 16 per cent completing theentire course. Level III students dropped outmore quickly than in Level II, but had the sameLanguage and Language Teachingcompletion rate of 16 per cent. The overalldropout rate, calculating from enrollment in Unit1, Level I, to completion of Unit 16, Level III,was similar to that reported by Nielson at 98.8per cent.Ridgeway et al. (2016) noted that there was a“sawtooth” pattern in the data, in that the numberof students completing the final unit of Level Iwas lower than those starting Level II and thenumber of students finishing Level II was lowerthan those starting Level III. They attributedVolume 8 Number 1 Issue 15 January 201948

this to the fact that “students tend to drop outwithin a level of a course, and new studentsjoin at the beginning of each of the three levels”(p. 931).DiscussionDespite the use of very different methodologiesand datasets, all three studies reviewed herereported similar outcomes: the number ofstudents who make it to the end of independentself-study language courses is very small, fallingsomewhere between 1 and 16 per cent. At best,independent students appear to do no better, andusually worse than those enrolled in traditionallanguage courses in high school and college.Nielson’s (2011) concluded from her data thatindependent adult language students wouldbenefit from more “support” such as thatoffered in a traditional language classroom.However, attrition rates are only marginallybetter for students enrolled in “high-support”high school and college classes with liveteachers. Indeed, it appears from Ridgeway etal. (2016), that those who enroll in the upperlevel courses fare about the same as those inregular classrooms (roughly 16 per centcompletion rate).All three studies suffer from a potential designweakness, one that McQuillan (2008) noted:students who receive a free course may be lessmotivated than those who have paid for it. Inboth McQuillan (2008) and Nielson (2011), usersof the course materials did not have to pay forthe materials. Ridgeway et al. (2016), analyzeddata from “institutional” users, where it waslikely that the institution and not the individualuser had purchased access to the software.Ridgeway and colleagues also note that “[s]omeinstitutions mandate the use of the software;others make the use optional,” but “[w]e haveno means of determining usage policy governingindividual students” (p. 931).Language and Language TeachingThere is some evidence that many onlinecourses suffer from high attrition. Jordon (2015)examined the attrition rates of 129 “MassiveOpen Online Courses” (MOOCs), free coursesfor adults in a variety of fields, offered throughwebsites such as Coursera and Open2Study.She found that the average completion rate forthe MOOCs was 12.6 per cent, with shortercourses (fewer than five weeks) and those withauto-graded assessments doing the best atretaining students. This completion rate is in therange of the best-case scenario for languagecourses, at least at the upper levels.Many adults who begin their self-study languagecourses probably do so with the goal of beingfluent, or at least conversant, in the language.The data reviewed here indicates that this rarelyhappens. One possible cause of low completionrates may be poor teaching methods. Krashen(2013) noted that the language instructionprovided by the most popular self-study course,Rosetta Stone, was “not very interesting, and along way from compelling” (p. 2). He concludedthat the limited amount of evaluation data onthe program provided “only modest support forits effectiveness” and that “studies do not agreeon users’ reactions” to the course (p. 2).Similar problems of uninspiring languageteaching have been reported in studiesof traditional classrooms. Tse (2000) notedthat research from the 1970s found that a largepercentage of students found their foreignlanguage classes “un-stimulating anduninteresting” (p. 72). McQuillan (1994) reportedthat one of the most common yet least effectivesecond language classroom activities, grammarstudy, was judged to be far less interesting forundergraduate students when compared to ararely used but more effective approach,sustained silent reading (Krashen, 2004). Yetall the courses in the three studies reviewedhere relied largely

To measure the program’s effectiveness, Rosetta Stone students were given proficiency interviews over the phone, in which they were asked to identify and describe pictures similar to the ones that appeared in their course. The tests were administered after the completion o