Transcription

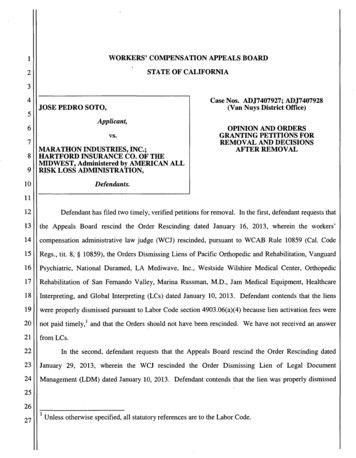

Department of Health and Human ServicesDEPARTMENTAL APPEALS BOARDCivil Remedies DivisionIn the Case of:Catherine Dodd,Petitioner,- v. The Inspector General.))))))))))DATE: March 16, 1992Docket No. C-384Decision No. CR184DECISIONOn April 18, 1991, the Inspector General (I.G.) notifiedPetitioner that she was being excluded from participationin Medicare and State health care programs for a periodof five years. 1 The I.G. told Petitioner that she wasbeing excluded as a result of her conviction of acriminal offense related to the delivery of an item orservice under Medicare. Petitioner was advised that theexclusion of individuals convicted of such an offense ismandated by section 1128(a)(1) of the Social Security Act(Act). The I.G. further advised Petitioner that therequired minimum period of such an exclusion is fiveyears. The I.G. informed Petitioner that she was beingexcluded for the minimum mandatory five year period.On May 8, 1991, Petitioner timely requested a hearing andthe case was assigned to me for hearing and decision.The I.G. moved for summary disposition. Petitioner fileda written response to the I.G.'s motion for summarydisposition.On November 8, 1991, I issued a ruling which denied theI.G.'s motion for summary disposition on the grounds thatthe I.G. had not proven that Petitioner was convicted of1 "State health care program" is defined by section1128(h) of the Social Security Act to cover three typesof federally-financed health care programs, includingMedicaid. I use the term "Medicaid" hereafter torepresent all State health care programs from whichPetitioner was excluded.

2a criminal offense related to the delivery of a Medicareor Medicaid item or service. In that ruling, I statedspecifically that the evidence presented by the I.G. wasinsufficient to establish that Petitioner had beenconvicted of a criminal offense within the meaning of§1128(a)(1). I provided examples of evidence which wouldmeet the statutory test for a conviction related to thedelivery of a Medicare or Medicaid item or service.Ruling Denying the Inspector General's Motion for SummaryDisposition, November 8, 1991.I gave the I.G. until December 16, 1991 to renew hismotion for summary disposition. The I.G. timely renewedhis motion. During a January 31, 1992 telephoneconference, I advised the I.G. that the documents whichhe submitted in connection with his initial and renewedmotion for summary disposition still did not provideproof that Petitioner had been convicted of a criminaloffense within the meaning of section 1128(a)(1). 2However, because my November 8, 1991 ruling did notspecifically state that I would decide the case in favorof Petitioner in the event the I.G. did not meet hisburden, I told the I.G. that I would allow him untilFebruary 14, 1992 to again either renew his motion forsummary disposition or to advise me that he desired anin-person evidentiary hearing. I further advised theI.G. that, if he elected again to move for summarydisposition and again failed to satisfy me that he hadestablished a basis for excluding Petitioner undersection 1128(a)(1), I would enter summary disposition inPetitioner's favor.On February 14, 1992, the I.G. submitted his secondrenewed motion for summary disposition. I have carefullyconsidered the evidence offered by the I.G. in connectionwith his initial motion for summary disposition and inhis two renewed motions. For purposes of this decision,I have accepted all of the Tacts as alleged by the I.G.as true. I conclude that the I.G. has not establishedthat Petitioner was convicted of a criminal offensewithin the meaning of section 1128(a)(1) of the Act. TheI.G. has not proved that he has authority to excludePetitioner under that section. Therefore, I enter2 This conference was conducted withoutPetitioner's participation. Several attempts were madeto advise Petitioner of the conference. However, thetelephone number which Petitioner had provided forcontact purposes was no longer valid, and Petitioner didnot respond to written notification sent to her lastknown address.

3summary disposition in favor of Petitioner, vacating theexclusion imposed and directed against her by the I.G.ISSUEThe issue before me in this case is whether Petitionerwas convicted of a criminal offense related to thedelivery of an item or service under Medicare or Medicaidwithin the meaning of section 1128(a)(1) of the Act.FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW1.On May 31, 1990, Petitioner pled guilty to, and wasconvicted of, the offense of knowingly or intentionallymaking a false written statement to obtain property, inviolation of Texas Penal Code Annotated, Section 32.32.I.G. Ex. 1; Hughes Aff. 1. 32. Petitioner admitted that the criminal activity forwhich she was convicted occurred on October 1, 1989.I.G. Ex. 1.3. The criminal charge against Petitioner, her plea ofguilty and conviction, resulted from an investigationconducted by the Texas Attorney General's Medicaid Fraud3 I refer to the I.G.'s original July 24, 1991,brief in support of motion for summary disposition asI.G. Br. (number/page). The I.G. attached four exhibitsto his first motion, which he designated as Exhibits 1through 4. I refer to the I.G.'s exhibits as I.G. Ex.(number designation)/(page). The I.G. also submitted thesworn affidavit of William J. Hughes, Program Analyst inthe I.G.'s Dallas office. Mr. Hughes's affidavit, unlikethe other I.G. submissions, was not marked as an exhibit.I refer to it as Hughes Aff. (page number). Petitionersubmitted her written reply to the I.G.'s motion and atypewritten letter that was originally sent by her to theTexas Department of Human Services to contest herexclusion. I will refer to Petitioner's typewrittenletter as Pet. Let. (page number). After my November 8,1991 Order, the I.G. submitted a renewed motion forsummary disposition and a supporting brief, which I referto as I.G. Mot. (page number). The I.G. attached oneexhibit to his renewed motion, which I refer to as I.G.Ex. 5. I refer to the I.G.'s second renewed motion,submitted on February 14, 1992 as I.G. Second Ren. Mot.The I.G. attached exhibits 6, 7 and 8 to his secondrenewed motion. I admit into evidence all I.G. exhibits,including the Hughes affidavit, and Petitioner's letter.

4Unit beginning November 27, 1989 at the BrookhavenNursing Center in Cheyenne, Texas. I.G. Ex. 2.4.Brookhaven Nursing Center is a medical facilityreceiving funds under the Texas Medicaid Program. I.G.Ex. 2.5. Petitioner admitted to Nora E. Longoria, theinvestigator for the Texas Attorney General's MedicaidFraud Unit, that she had converted for her own usemedications provided for four patients (Peggy Bang,Dorothy Crowson, Creda Hoga, and James Martin) and hadfalsified these patients' treatment records. I.G. Ex. 2.6. On November 28, 1989, Petitioner signed a statementwhich was witnessed by Ms. Longoria, in which Petitioneradmitted that, starting around the beginning of October,1989, she had converted to her own use medicationsprovided for residents at the Brookhaven NursingFacility. I.G. Ex. 8.7. In her statement, Petitioner admitted converting toher own use medication provided for patients, includingCreda Hoga, Dorothy Crowson, Peggy Bang, Gertrude Clark,and James Martin. I.G. Ex. 8.8. James Martin was not a resident at the BrookhavenNursing Facility on October 1, 1989. I.G. Ex. 6.9. Creda Hoga was a resident at the Brookhaven NursingFacility on October 1, 1989, and was a Medicarebeneficiary occupying a Medicare skilled nursing facilitybed as of that date. I.G. Ex. 6.10. Dorothy Crowson was a resident at the BrookhavenNursing Facility on October 1, 1989, and was eligible forMedicaid. I.G. Ex. 5.11. The I.G. did not prove that Brookhaven NursingFacility presented a claim to a Medicaid program foritems or services provided to Dorothy Crowson on October1, 1989. I.G. Ex. 6.12. Peggy Bang was a resident at the Brookhaven NursingFacility on October 1, 1989, and was eligible forMedicaid. I.G. Ex. 5.13. The I.G. did not prove that Brookhaven NursingFacility presented a claim to a Medicaid program foritems or services provided to Peggy Bang on October 1,1989. I.G. Ex. 6.

514. The I.G. did not prove that Gertrude Clark was aresident at the Brookhaven Nursing Facility on October 1,1989, and did not prove that Gertrude Clark was either aMedicare beneficiary or a Medicaid recipient.15. The Judgment of Conviction which was entered againstPetitioner does not name the individual whose medicalrecords were falsified by Petitioner. I.G. Ex. 1.16. The I.G. has not established by extrinsic evidencethe name of the individual whose medical recordsPetitioner was convicted of falsifying. See I.G. Ex. 1 8.17. Petitioner was convicted of a criminal offensewithin the meaning of section 1128(i) of the Act.18. The I.G. did not prove that Petitioner was convictedof a criminal offense related to the delivery of an itemor service under Medicare or Medicaid.19. There are no disputed issues of material fact inthis case and summary disposition is appropriate.20. The I.G. has not proven that he has authority toexclude Petitioner pursuant to section 1128(a)(1) of theAct.ANALYSISThe threshold issue in this case is whether Petitionerwas "convicted" of a criminal offense within the meaningof section 1128(i) of the Act. Petitioner's plea ofguilty to criminal charges in a Texas State court meetsthe statutory definition of conviction. Section1128(1)(3) defines a conviction to include thecircumstance where a plea of guilty has been accepted bya State court. Here, Petitioner pleaded guilty to acrime and that plea was accepted. Findings 1 and 17.The issue which is central to this case is whetherPetitioner was convicted of a criminal offense related tothe delivery of an item or service under Medicare orMedicaid program, within the meaning of section1128(a)(1) of the Act. Inasmuch as the I.G. excludedPetitioner pursuant to this section, the I.G. must showthat her conviction fell within the meaning of thatsection in order to establish that he had the authorityto exclude Petitioner.The relevant facts of this case are detailed below.Petitioner was employed as a nurse at the Brookhaven

6Nursing Facility, a Texas nursing facility which treatsboth Medicare beneficiaries and Medicaid recipients. OnNovember 27, 1989, an investigator from the TexasMedicaid Fraud Unit confronted Petitioner concerning adiscrepancy between a patient's records, which recordedthat the patient was being administered a prescriptionmedication, and the patient's assertion that, in fact,she was being administered another, nonprescriptionmedication instead. I.G. Ex. 2.Petitioner admitted to having converted to her own usemedications which had been provided for patients at theBrookhaven Nursing Facility and falsifying patients'treatment records to cover up these acts. She deniedhaving converted to her own use medication from thepatient whose statement prompted the investigation. I.G.Ex. 2. However, she admitted to the investigator havingconverted to her own use medication from four namedpatients (Peggy Bang, Dorothy Crowson, Creda Hoga, andJames Martin) and falsifying their treatment records.Id. On November 28, 1989, Petitioner signed a statementin which she admitted that "around the beginning ofOctober" 1989, she began taking medication from patients.I.G. Ex. 8. In that statement, she named the patientswhose medications she had converted to her own use asincluding Creda Hoga, Dorothy Crowson, Peggy Bang,Gertrude Clark, and James Martin. Id.On May 31, 1990, Petitioner pleaded guilty in a TexasState court to the criminal charge of making a falsestatement to obtain property. The Judgment of Convictionand Sentence recites that the offense to which Petitioneroccurred on the first day of October, 1989. I.G. Ex. 1.The document does not state the particulars ofPetitioner's offense. Specifically, it does not identifythe false statement which Petitioner made or thecircumstances under which it was made. Id. The I.G. hasoffered no evidence from either the State court or fromother sources connected with Petitioner's conviction(such as the prosecuting attorney) which would explainthe circumstances of the offense of which Petitioner wasconvicted.However, it is reasonable to infer that Petitioner'sconviction emanated from the investigation at theBrookhaven Nursing Facility and Petitioner's admissionsto the Medicaid investigator. In her report, theinvestigator recommended that Petitioner's case bereferred to the local prosecutor. I.G. Ex. 2.Petitioner's admission of having begun convertingpatients' medication and altering their treatment recordsaround the beginning of October, 1989, closely dovetails

7with the October 1, 1989 date of the offense recited inthe Judgment of Conviction and Sentence. I.G. Exs. 1, 8.Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude Petitioner'sconviction of a single count of making a false statementto obtain property relates to an episode in whichPetitioner falsified the treatment records of at leastone of the patients whose medication Petitioner admittedconverting to her own use. These individuals include,but by Petitioner's admission, are not limited to, CredaHoga, Dorothy Crowson, Peggy Bang, Gertrude Clark, andJames Martin.The I.G. offered evidence which establishes that, as ofOctober 1, 1989, James Martin was not a patient at theBrookhaven Nursing Facility. His admission to thefacility began on October 18, 1989. I.G. Ex. 6.Therefore, Mr. Martin could not be the patient whoserecords Petitioner was convicted of having falsified onOctober 1, 1989.The I.G. has offered no evidence concerning GertrudeClark. It is therefore not established that she was apatient at the Brookhaven Nursing Facility on October 1,1989, nor is it established that Ms. Clark was receivingeither Medicare or Medicaid items or services at thefacility.The I.G. has established that, as of October 1, 1989,Creda Hoga was occupying a Medicare skilled nursingfacility bed at the Brookhaven Nursing Facility. I.G.Ex. 5. The I.G. has also established that DorothyCrowson and Peggy Bang were eligible for itmes orservices under the Texas Medicaid program, and that PeggyBang was eligible for Medicare while at Brookhaven. I.G.Exs. 5, 6. However, the I.G. has offered no evidence toshow that these patients' stays in the facility or anyitems or services which they received during their stayswere covered by the Texas Medicaid program. Moreimportantly, the I.G. has not shown, with respect toCrowson and Bang, that these patients received anyMedicare or Medicaid items or services on October 1,1989, the date that, according to the criminalinformation, provides the basis for Petitioner'sconviction. I.G. Ex. 7.The I.G. asserts that, based on these undisputed materialfacts, he has proven that Petitioner was convicted of acriminal offense within the meaning of section 1128(a)(1)of the Act. I disagree. The evidence fails to provethat Petitioner was, in fact, convicted of a criminaloffense related to the delivery of an item or service

8under Medicare or the Texas Medicaid program. Althoughthe I.G. has offered evidence which shows that theoffense of which Petitioner was convicted might berelated to the delivery of a Medicare or Medicaid item orservice, he has not adduced sufficient proof to establishthat the conviction is related to the delivery of aMedicare or Medicaid item or service. The I.G. has thusfailed to meet his duty to establish proof of authorityto exclude Petitioner under section 1128(a)(1).In his initial motion for summary disposition, the I.G.asserted that the requisite nexus for a conviction undersection 1128(a)(1) was established by virtue of the factthat Petitioner was employed at a nursing home whichtreated Medicare and Medicaid patients and committed acrime during the course of her duties at that facility.As I announced in my November 8, 1991 ruling, I was notpersuaded by that argument, and I restate the reasonshere.Section 1128(a)(1) specifically requires that, as a basisfor an exclusion, a party must be convicted of a criminaloffense related to the delivery of an item or serviceunder Medicare or Medicaid. The fact that an individualcommits a crime during the course of his or heremployment by a facility which receives Medicare orMedicaid reimbursement is not in and of itself sufficientto meet the statutory test, because such a convictionwould not necessarily relate to the delivery of aMedicare or Medicaid item or service.The I.G.'s theory, expressed in his initial motion forsummary disposition, is so broad as to make any criminaloffense committed on the premises of a facility whichreceives Medicare or Medicaid reimbursement a criminaloffense within the meaning of section 1128(a)(1). Thelogical extension of his argument would, for example,encompass a simple battery by an employee on a coworker.This analysis departs from the plain meaning of the Act.Furthermore, it would make section 1128(a)(1) so broad inits application as to render virtually meaningless theremainder of sections 1128(a) and (b).The Act does not define the term "criminal offenserelated to the delivery of an item or service." However,a criminal offense has been held to meet the statutorytest where the delivery of an item or service is anelement in the chain of events giving rise to the item orservice. Jack W. Greene DAB 1078 (1989); aff'd sub nom.Greene v. Sullivan, 731 F. Supp. 835, 838 (E.D. Tenn.1990) (Greene); Larry W. Dabbs, R. Ph. et al., DAB CR151(1991) (Dabbs). A criminal offense has also been held to

9meet the statutory test where Medicare or a Medicaidprogram was the victim of a party's criminal offense.Napoleon S. Maminta, M.D., DAB 1135 (1990) (Maminta).In Greene, the petitioner was convicted of filing afraudulent Medicaid reimbursement claim. An appellatepanel of the Departmental Appeals Board held that theoffense was an offense within the meaning of section1128(a)(1), inasmuch as it arose from the providing of aMedicaid item or service (a prescription for a Medicaidcovered drug). In Dabbs, the petitioners were convictedof the crime of mislabeling drugs. I concluded that thisoffense was related to the delivery of a Medicaid item orservice. The basis for my conclusion was that the act ofmislabeling grew out of events which necessarily includedthe petitioners' filling certain prescriptions forMedicaid items or services and presenting Medicaidreimbursement claims for those items or services.In Maminta, an appellate panel sustained findings thatthe petitioner had been convicted of a criminal offenseconsisting of unlawfully converting to his use a Medicarereimbursement check which was payable to another party.The appellate panel held that petitioner had beenconvicted of a criminal offense within the meaning ofsection 1128(a)(1), in that Medicare was the victim ofhis crime.The I.G. has not contended that Petitioner was convictedof having converted to her use medications which belongedto Medicare or Medicaid. Nor has the I.G. asserted thatthese programs were the victims of Petitioner's crime.Therefore, the I.G. is not arguing that Petitioner'soffense falls within the Maminta test.Thus, in order for me to find that Petitioner wasconvicted of a criminal offense within the meaning ofsection 1128(a)(1), I must find some nexus betweenPetitioner's conviction and an identified Medicare orMedicaid item or service. The starting point fordeciding whether the test has been met here is to analyzethe status of the patients whose medications wereconverted by Petitioner and whose records were falsified.However, as I stated in my November 8, 1991 ruling, thatis only the starting point of the analysis.The document containing Petitioner's guilty pleaidentifies the date on which her crime occurred (October1, 1989) and the nature of her offense (making a falsestatement to obtain property). It does not identify thespecific false statement made by Petitioner. Therefore,it is not possible to ascertain from this document

10w

Unit beginning November 27, 1989 at the Brookhaven Nursing Center in Cheyenne, Texas. I.G. Ex. 2. 4. Brookhaven Nursing Center is a medical facility receiving funds under the Texas Medicaid Program. I.G.