Transcription

Connecticut’s AlliedHealth Workforce:Challenges andOpportunitiesA report by the Allied Health Workforce Policy BoardJanuary 2015

BackgroundIn 2004, Connecticut’s legislature established the Connecticut Allied Health Workforce Policy Board (AHWPB) (Public Act04-220) to conduct research and planning activities related to the allied health workforce. According to the legislation,the responsibilities of this board include:1. Monitoring data and trends in the allied health workforce including, but not limited to:a. The state’s current and future supply and demand for allied health professionals; and,b. The current and future capacity of the state system of higher education to educate and train studentspursuing allied health professions.2. Developing recommendations for the formation of an economic cluster for allied health professions.3. Identifying recruitment and retention strategies for institutions of higher education with allied healthprograms.4. Developing recommendations for promoting diversity in the allied health workforce including but not limitedto racial, ethnic and gender diversity, and for enhancing the attractiveness of allied health professions.5. Developing recommendations regarding financial and other assistance to students enrolled in or consideringenrolling in allied health programs offered at public or independent institutions of higher education.6. Identifying recruitment and retention strategies for allied health employers.7. Developing recommendations about recruiting and utilizing retired nursing faculty members to teach or trainstudents to become licensed practical nurses or registered nurses.8. Examining nursing programs at institutions of higher education and developing recommendations about thepossibility of streamlining the curricula offered in such programs to facilitate timely program completion.The Allied Health Workforce Policy Board is overseen and supported by the Connecticut Department of Labor, Office ofWorkforce Competitiveness on behalf of the CT Employment and Training Commission.Allied Health Workforce Policy Board members are:Frances Padilla, co-convener, Universal Health Care FoundationStuart Rosenberg, co-convener, St. Francis Hospital and Medical CenterMark Bain, VA Connecticut Healthcare SystemTricia Harrity, Northwestern AHECElizabeth Beaudin, Connecticut Hospital AssociationKim Kalajainen, Lawrence and Memorial HospitalPatricia Bouffard, CT State Board of Examiners forStephen J. Mordecai, Griffin HospitalNursingSherry Ostrout, Connecticut Community Care, Inc.John Capobianco, Charlotte Hungerford HospitalDeborah Parker, Eastern Connecticut Health NetworkJoseph Cappa, Connecticut GIGregory Paveza, Southern Connecticut StatePatricia Fennessey, CT Technical High School SystemUniversity/Board of RegentsMargaret Flinter, Community Health CenterPatricia Santoro, State Office of Higher EducationMerle Harris, Retired President, Charter Oak StateBetsey Smith, Quinnipiac University/ConnecticutCollegeConference of Independent CollegesKathy Marioni, CT DOL, Office of WorkforceKristin Sullivan, State Department of Public HealthCompetitivenessAlice Pritchard, Executive Director of the Connecticut Women’s Education and Legal Fund, serves as a consultant to theBoard on behalf of the CT Employment and Training Commission. For more information on the Board’s activities, pleasevisit: ndustrySectors/AlliedHealth/AlliedHealth.htm, or contact Dr.Pritchard at 860-247-6090 or apritchard@cwealf.org.2

Table of ContentsIntroduction. 4Reforms Impacting the Health Care Workforce . 4Additional Factors Affecting the Demand for Health Care Workers . 5Connecticut’s Health Care Workforce: Supply and Demand Analysis in Key Industry Areas . 7Primary Care/Public Health. 10Behavioral Health . 12Long-term Services and Supports . 14Health Information Technology/Management . 16Building A Skilled Workforce: Challenges Facing Individuals and Institutions. 18Priority Areas and Recommendations. 21Conclusion . 23References . 243

IntroductionIn 2004, Connecticut’s legislature established the Connecticut Allied Health Workforce Policy Board (AHWPB)(Public Act 04-220) to conduct research and planning activities related to the allied health workforce. TheBoard began meeting in March 2005 and issued its first report to the legislature in February 2006, followed byannual reports. Since 2004, the AHWPB has convened employers and educators in the healthcare fields to sharetheir data on the workforce, knowledge about what shortages exist, and to make recommendations to thelegislature on how to prepare the current and future workforce for industry demands.The AHWPB has been monitoring reforms driven at the state and federal level, which will profoundly change theway in which healthcare will be delivered in Connecticut in the future. The implementation of the AffordableCare Act (ACA) combined with the growing healthcare needs of America’s aging population and the utilization ofnew technologies is impacting the delivery of health care services. This report provides an update to the June2014 (link) report, which highlights federal and state health care reforms as well as the supply and demand forhealth care workers and the challenges associated with preparing that workforce for the next generation ofhealth care delivery. The report concludes with priority focus areas to address Connecticut’s workforcechallenges.Reforms Impacting the Health Care WorkforceThe Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (H.R.3590) and the Health Care Education and Reconciliation Act(H.R.4872), together known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), strive to achieve the “Three Part Aim”: improvingthe experience of care for individuals, improving the health of populations, and lowering per capita costs. Inorder to achieve these goals, the existing payment models and health care delivery system need to be reformed.The ACA aims to move the health care system away from its current episodic, fee-for-service payment approachand towards a coordinated model that is focused on delivering high-quality, low-cost care across the continuumof care. In addition to changing the method through which providers are paid for health care, it is also necessaryto reform the way in which that care is delivered, i.e., reforming the delivery system by creating high-performingorganizations of physicians and hospitals that use systems of care and information technology to prevent illness,improve access to care, improve safety, and coordinate services (http://www.accountablecarefacts.org). Thesechanges will have a direct impact on the skills demanded of current and future workers in health care in bothnonclinical and frontline positions (Alssid & Goldberg, 2013).In 2011, a Health care Cabinet was established in Connecticut to advise the Governor and Lt. Governor on issuesrelated to implementing ACA and the development of an integrated health care system for the state. In March2013, the Governor’s office received a 2.8 million planning grant from the Centers for Medicaid and MedicareInnovation (CMMI) to develop a State Healthcare Innovation Plan. The State Innovation Model (SIM) planfocuses on achieving better health, while eliminating health disparities; improving health care quality andexperience; and lowering health care costs (CT Healthcare Innovation Plan, 2013). In December 2014,4

Connecticut was awarded 45 million in federal funds to implement the SIM plan as part of 620 millionawarded to 11 states under the ACA.In addition to planning for the implementation of the ACA, Connecticut is leading other reforms as well. MoneyFollows the Person (MFP) is a multi-million dollar federal demonstration grant, received by the ConnecticutDepartment of Social Services in 2007. It is intended to rebalance the long-term care system so that individualshave the maximum independence and freedom of choice of where they live and receive services. There areseveral inter-related initiatives in MFP including workforce development; hospital discharge planning; long-termservices; and nursing home right-sizing.In 2011, building on the early work of MFP, Connecticut undertook a major planning effort related to long-termcare known as Connecticut’s Strategic Rebalancing Plan (Rebalancing). Rebalancing aims to increase choice ofwhere people receive long-term services and supports while supporting cost efficiencies in the Medicaidprogram. In SFY 2014, of those receiving Medicaid long-term care services, 59% received care in a home orcommunity-based setting, and 41% in an institution. 1 By 2025, Rebalancing goals would shift that ratio to 75%receiving long-term care in a home or community based setting, and only 25% in an institution.The AHWPB is monitoring these efforts and has invited presentations throughout the year to align effortsimpacting the workforce. In partnership with state sponsored efforts such as the SIM planning, Rebalancing, andMFP, the AHWPB can help position Connecticut businesses and workers for these changes by keeping statepolicy makers and stakeholders abreast of these efforts and providing recommendations for future action.Additional Factors Affecting the Demand for Health Care WorkersA number of factors will impact the health care workforce in the years ahead. For instance, the model of caredelivery will shape workforce demand. To the extent that medical homes are adopted, the clinical shortagecould be lessened because of the reliance on other care providers and non-clinical staff. In addition, front lineworkers could see their roles and tasks expand without change in compensation or job advancement, and someemployers may hire lower-paid and lower-skilled workers to reduce staff at higher levels (Wilson, 2014).Employers interviewed for a 2014 Jobs for the Future study could not predict their staffing needs in the comingyears in large part due to the uncertainty of the impact of health care reform. Major hospitals in Connecticut,Ohio, Virginia and other states announced cutbacks in 2013 due to the cuts in Medicare and Medicaid funding(Wilson, 2014). In many cases efforts were focused on training current staff to fill openings, not on developingexternal pipelines (Wilson, 2014). According to the report, experts claim that tens of millions of new patients willrequire an upsurge in hiring new workers, particularly in primary care (Wilson, 2014).The Connecticut’s hospital system continues to experience fundamental changes in its organizational form andthe structure of its health care providers. Between 2009-2013, there were 13 attempts and seven successfulhospital consolidations and/or partnerships, a substantial increase from the previous decade (Kaylin, 2013). Of1Rebalancing: Medicaid Long-Term Care Clients and Expenditures. SFY 2014.5

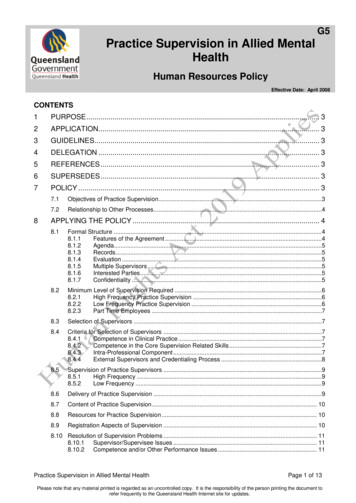

the 29 acute care hospitals in the state, 16 are now currently part of a larger hospital parent company, and someof the remaining 13 are affiliated with out of state hospital networks. These partnership and affiliations arecausing uncertainty in hiring as operations are consolidated and the need for employees across different fields isunder review.The future demand for health care workers will be impacted by the current age of the workforce. As shownbelow in Table 1, health care related employment data by age indicated that 24% of employees are between theages of 45-54 and 19% are between the ages of 55-64. 2Table 1. Connecticut Health Care Employment by Age 2013 Q41% -6465-99Source: U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators (QWI)A 2014 report by the Connecticut League for Nursing (CLN) suggests that in a recent survey of 1,661 registerednurses, 51% are 55 and older (CLN, 2013). As shown in Table 1, as demand increases in the years ahead,employers will need to be ready to replace almost 25% of their workforce.Another factor that will impact the workforce and projected openings is Connecticut’s aging population whichwill require increased health care services, such as nursing and residential care. Connecticut is ranked secondamong states with the highest percentage of the population in both the ‘Aged 90 and Over’ and ‘Aged 65 andOver’ categories. 3 In 2013, Connecticut population aged 65 and older was 15.2% of the overall population. 4 In2015, that percent is projected to increase to 15.98% and by 2020 it will be 18.12%. 5Health care needs related to an aging population will also require a shift in delivery models. For example, growthin long-term services and supports brought about through Rebalancing will shift the delivery of care fromresidential facilities toward community based services, redistributing the workforce from skilled nursing facilities2U.S. Census Quarterly Workforce Indicators (QWI). Retrieved on 12.5.14.State of CT Department of Social Services. 2013. Strategic Rebalancing Plan: A Plan to Rebalance Long Term Services andSupports 2013-2015.4US Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 1/29/145CT State Data Center. CT Population Projections. Retrieved 12/5/14.36

to home care agencies. This shift will require home care workforce to have a different set of skills, such as theability to work autonomously, thereby making the type of care needed in the home will become more complex.The Connecticut General Assembly’s (CGA) Alzheimer’s Task Force report found that 70% of individuals withAlzheimer’s or related dementia reside in the community, and this is likely to increase the demand for homecare services and supports (CGA, 2013). Of those with dementia who live in the community, 75% live withsomeone and the remaining 25% live alone (CGA, 2013). As the number of individuals with Alzheimer’s in theUnited States is expected to increase substantially over the next few decades, the long term care workforce willneed to expand in size to meet demand and receive enhanced training to provide better services.Connecticut’s Health Care Workforce: Supply and Demand Analysisin Key Industry AreasConnecticut’s health care workforce continues to be one of the largest in the state and is projected to continuegrowing over the next ten years. The CT Department of Labor reports that Health Care and Social Assistance isthe largest sector in Connecticut.Connecticut’s total employment in October 2014 was 1,694,600, with employment in health related occupationswas 265,000. 6 The CT Department of Labor projects, the employment level for Health Care and Social Assistanceoccupations will increase to 331,339 by 2022, a 19.9% increase for the ten-year period. 7Table 2 highlights occupation projections for 2012-2022 indicating the number of projected openings and thepercentage increase in those openings. Some occupations have significant numbers of new workers anticipated.Others may have high percentage changes over the ten-year period, but a smaller numerical change. Forinstance, registered nurses (RNs) show a high numeric change (5,249) while Occupational Therapy Assistantshave a high percentage change of 35.4%, but only 174 projected new jobs over the ten-year period. The AHWPBhas focused its analysis on occupations with high numeric change such as Personal Care Aides (PCAs), PhysicalTherapists (PTs), Medical Assistants (MAs) and Home Health Aides (HHAs). All of these workers will be critical tothe full implementation of the ACA and the focus on primary care.Data from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) suggests the demand for RNs and LPNs willbe met in Connecticut if our current graduation rates continue through that time period. The HRSA modelestimates, which are comparable to the Bureau of Labor Statistic’s job growth estimates, show a slight oversupply of both professionals by 2025.67CT Department of Labor, CT Total and Healthcare Employment. October 2014.CT Department of Labor, State of CT Industry Projections 2010-2020. Retrieved on 12/5/14.7

Table 2. CT Occupational Projections 2012-2022Sample Health Care OccupationsHealth Diagnosing and Treating PractitionersPersonal Care AidesRegistered NursesNursing, Psychiatric, and Home Health AidesHome Health AidesMedical AssistantsLicensed Practical and Licensed Vocational NursesPhysical TherapistsNursing AssistantsEmergency Medical Technicians and ParamedicsNurse PractitionersOccupational Therapy and Physical Therapist Assistants andAidesPhysician AssistantsPharmacy TechniciansRadiologic TechnologistsDiagnostic Medical SonographersOccupational TherapistsDental AssistantsMedical and Clinical Laboratory TechniciansPharmacistsMedical Records and Health Information TechniciansHealth Technologists and Technicians, All OtherPhlebotomistsPhysical Therapist AidesPhysical Therapist AssistantsOccupational Therapy AssistantsFamily and General PractitionersDietitians and NutritionistsMedical and Clinical Laboratory 3.937.435.412.117.15.9Source: CTDOL Occupational Projections 2012-2022. 20148

Much of the health care workforce requires education beyond high school, and will need to be trained inConnecticut’s institutions of higher education. In 2013, Connecticut public and private colleges and universitiesgraduated over 4,500 students in health care related programs. As shown in Table 3, while most occupationalareas have sufficient graduates to meet the ten year demand, a number of occupations need focused attentionfor recruitment to meet projected openings. These occupations include diagnostic medical sonographers,medical records and health information technicians, and radiologic technologists and technicians.Table 3. Occupational Projections and Related CT College and University n AssistantsOccupational TherapistsRegistered NursesRadiation TherapistsRespiratory TherapistsCardiovascularTechnologists andTechniciansDiagnostic 19467,23960779018330.19991,382383Radiologic TechnologistsOccupational TherapyAssistantsPhysical TherapistAssistantsEmergency

, CT DOL, Office of Workforce Competitiveness . Tricia Harrity, Northwestern AHEC . Kim Kalajainen, Lawrence and Memorial Hospital . Stephen J. Mordecai, Griffin Hospital . Sherry Ostrout, Connecticut Community Care, Inc. Deborah Parker, Eastern Connecticut Health Network . Gregory Paveza, Southern Connecticut State University/Board of Regents