Transcription

Boletín de la SociedadMexicana de Ficologíay de la SociedadFicológica de AméricaLatina y el CaribeNo. 3, abril 2014

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 32COMITÉ EJECUTIVO NACIONALSociedad Ficológica de América Latina y el Caribe: 2012-2014http://www.sofilac.com/Dr. Francisco F. PedrochePresidenteDepartamento de CienciasAmbientales, División CienciasBiológicas y de la Salud. UAM-Lerma.e-mail: fpedroche@correo.ler.uam.mxDra. Jhoana Díaz LarreaTesoreraDepartamento de Hidrobiología,División Ciencias Biológicas y de laSalud. UAM-Iztapalapa.e-mail: jhoanadiazl@yahoo.comDra. Ma. Esther A. Meave delCastilloSecretaria EjecutivaDepartamento de Hidrobiología,División Ciencias Biológicas y de laSalud. UAM-Iztapalapa.e-mail: mem@xanum.uam.mxDr. José Áke CastilloEditor ejecutivoUnidad de Investigación deEcología de Pesquerías,Universidad Veracruzanae-mail: aake@uv.mxDr. Abel Sentíes GranadosVocal AcadémicoDepartamento de Hidrobiología,División Ciencias Biológicas y de laSalud. UAM-Iztapalapa.e-mail: asg@xanum.uam.mxEDITORES DEL BOLETÍNDr. Eberto Noveloenm@ciencias.unam.mxDr. Abel Sentíes Granadosasg@xanum.uam.mxDr. Juan M. Lopez-Bautistajlopez@ua.eduM. en C. María Eugenia ZamudioVocal de DifusiónDepartamento de Hidrobiología,División Ciencias Biológicas y de laSalud. UAM-Iztapalapae-mail: maruzarc@xanum.uam.mxPara publicar en este Boletín, enviarsus propuestas a los editores. Políticasy normas en página 23.Números anteriores en mx/

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 33MENSAJE DEL PRESIDENTEDE LA SOCIEDAD MEXICANA DE FICOLOGÍA Y DE LA SOCIEDADFICOLÓGICA DE AMÉRICA LATINA Y EL CARIBEDurante los próximos dos años (2014-2015) el presente boletín será el órganoinformativo de dos Sociedades: la Sociedad Filológica de América Latina y el Caribe yla Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología. Precisamente, durante estos dos años las mesasdirectivas de ambas asociaciones trabajaremos conjuntamente para beneficio deambas agrupaciones.En los tiempos actuales todas las instituciones, con variaciones dependiendo del paísque se trate por supuesto, están obligadas a buscar formas nuevas de lograr susobjetivos, con la visión de aprovechar mejor sus recursos y lograr resultadostangibles y concretos como efecto lógico de una planeación y del trabajocolaborativo entre los miembros de la agrupación.Los problemas que enfrentamos de principio son complejos y deben de serabordados en el concierto con otras disciplinas, para crear lenguajes comunes y deahí la trascendencia de construir Sociedades que fomenten la transdisciplina.

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 34En este sentido, un boletín informativo es crucial en la comunicación e intercambiode ideas, proyectos y logros. La construcción de conceptos ad hoc, de métodospertinentes y apropiados, la discusión de resultados y la propuesta de alternativas,nacen precisamente de este diálogo entre pares, de distintos países y conformaciones diversas.A la par con el boletín, publicación periódica, debemos construir páginaselectrónicas actualizadas y que en tiempo real nos informen, por medio dedirectorios, perfiles de investigación, publicaciones, alumnos en formación, regionesgeográficas en estudio, de las herramientas electrónicas que facilitan y hacen másexpedita la realización de nuestro trabajo cotidiano.Otros instrumentos de ayuda y que aprovecharemos, son las redes sociales. De estas,a la fecha contamos con una cuenta en Facebook y hemos alentado la inscripción delos agremiados a ResearchGate, una propuesta novedosa de cómo calificar el trabajode investigación, pero sobre todo que permite la vinculación e intercambio entreprofesionales que poseen intereses similares.Todos estos instrumentos deberán estar enfocados a los problemas inmediatos denuestras Sociedades como: la cooperación mexicana, latinoamericana eiberoamericana, como una prioridad importante para después o paralelamente,acrecentar los lazos con otras regiones del planeta con problemas similares; laactualización continua a niveles licenciatura y postgrado; la concreción de convenioscon otras Sociedades, IES, ONG entre otras, para construir redes científicas quepuedan, en el corto plazo, establecer estudios o investigaciones de largo aliento enregiones geográficas de interés común; la preparación de líderes de la ficología encada región de los países miembros, por mencionar sólo algunos.A nombre de las dos Sociedades agradezco el esfuerzo y dedicación, así como lasideas extraordinarias de nuestros editores, que hacen de este boletín un medioindispensable en la vida de nuestras asociaciones.Francisco F. PedrochePresidenteSociedad Ficológica de América Latina y el Caribe (2012-2015)Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología (2014-2017)

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 35EDITORIALCon el tercer número del Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología se inicia una etapadistinta para esta publicación. Por dos años será también el Boletín informativo de laSociedad Ficológica de América Latina y el Caribe. Y es momento para rendir un homenaje alas editoras del primer Boletín Ficológico Latinoamericano: Dra. Marilza Cordeiro-Marino,Dra. Rosario de Almeida Braga y Dra. Maria Teresa de Paiva Azevedo, quienes mantuvierondurante el periodo 1987-1990 una publicación útil y de alta calidad. En 1993, coincidiendocon el 3er. Congreso Latinoamericano de Ficología y la Primera reunión Iberoamericana deFicología en México, apareció el número 5 de ese Boletín en el que se incluyeron lasdirecciones de 1253 personas relacionadas con el estudio de las algas en esta gran región. Porsu parte, la Sociedad Mexicana publicó Boletines informativos hasta 1998.Así con este Boletín de las Sociedades Mexicana y Latinoamericana y del Caribe, sostenemosla idea de que las sociedades científicas requieren de un medio de comunicación con susmiembros. La publicación de una revista y de un boletín informativo fue planteada en variasocasiones e incluso aparece como parte de los estatutos de la Sociedad Ficológica deAmérica Latina y el Caribe pero no prosperó ninguna iniciativa al respecto. Las opcioneseditoriales han cambiado desde 1987 y por ello nuestra propuesta es un tanto intermedia, unboletín que ofrezca información calificada, comentarios y opiniones que puedan despertar elinterés por las algas, además de información que no caduque o que sirva de referenciaposterior. Un publicación tipo “newsletter” tiene la desventaja de parecer sobrepasado por lavelocidad de difusión que se alcanza en internet. Una publicación científica requiere de unapoyo financiero y organizativo de tipo institucional o de la Sociedad que no tenemos porahora. Una publicación que se mantenga en el intermedio es un reto y una oportunidad deprobar nuestra capacidad de respuesta, de mantener la comunicación y de difundir laficología al mismo tiempo.En concordancia con lo anterior, en este número ofrecemos un artículo sobre metagenómicaen el estudio de algas subaéreas que promueve la utilización de las técnicas moleculares parael estudio de la diversidad. Invitamos a los lectores a mandar su opinión y sobre todo susresultados relacionados con estos temas. Las ilustraciones muestran varias facetas deespecies de Nostoc, en cultivo y de muestras ambientales, una Cyanoprokaryota típicamentesubaérea. También se incluye información del próximo Congreso Latinoamericano ynuestras secciones de Ficoweb y publicaciones recientes.Los invitamos cordialmente a colaborar y apoyar en la difusión de la ficología en México y enLatinoamérica. Este Boletín aparecerá tres veces al año: abril, agosto y diciembre.Atentamente,Los editores

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 36ARTÍCULO ORIGINALThe use of metagenomics to infer algal diversity in a subaerialcommunity from an African tropical rainforest, “Les Monts deCristal” national park, Gabon.Haj Allali, David Ward and Juan Lopez-Bautista *Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Alabama, P.O. Box 870345,Tuscaloosa, AL 35484-0345, U.S.A.*Author to whom correspondence should be addressed;Phone: 1(205) 348-1791, Fax: 1(205) 348-6460Email: jlopez@as.ua.eduAbstractThe usefulness of metagenomics inassessing the biodiversity of “Les Montsde Cristal” National Park in Gabon,Africa was tested. This region waschosen in the basis of its botanicalrichness that makes it highly amenablefor studies on the biodiversity ofsubaerial organisms and it isconsidered one of the richest in thecountry and in Central Africa. Treeswere sampled for subaerial algae byscrapping where microorganisms’growth was evident. A portion of thelarge subunit of the ribosomal DNA(23S) gene was chosen as the molecularmarker. This marker was successfullyamplified from both prokaryotes(cyanobacteria) and eukaryotes (nonvascular plants). The resultingsequences were placed taxonomicallyby reconstructing a phylogeny usingMaximum Likelihood (ML). Theanalysis consisted of 467 taxa includingabout 150 environmental 23S sequencesfrom Africa and the following groupswere represented within the “Monts deCristal” forest: cyanobacteria,chlorophyte green algae includingsome trentepohlialean taxa, diatoms,mosses, and liverworts. This studyshowed the usefulness of this markerand also represents an ineditedcontribution in subaerial algalbiodiversity because the terrestrialalgal flora of Les Monts de Cristal hasbeen overlooked and never assessedbefore.Keywords: Subaerial, “Les Monts deCristal”, Metagenomics, 23S rDNAIntroductionSince 1990’s, microbial ecology hasexperienced major revolutions in partdue to the constant developments ofgenomics and molecular biology.Initially, studies targeting the analysisof rDNA sequences obtained directlyfrom the environment, coupled withtraditional studies of microbiology,demonstrated that more than 98%microorganisms are not cultivableunder laboratory conditions (Ward etal. 1990). Consequently, theirmorphological or physiological featurescannot be characterized. A new field

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 37emerged, metagenomics, which is theanalysis of genomic DNA ofassemblages of organisms from theenvironment (Handelsman 2004).Cloning environmental DNA (withoutany prior cultivation) is a relatively newmethod to unravel the diversity foundin microalgal communities. Using suchmethods will help isolate phylotypes (adistinct, consistently found sequencethat is classified by its phylogeneticrelationship to other organisms) thatare new to science (Gabor et al. 2003).Most studies of algal diversity relied onculture and morphological charactersto separate different taxa. However,these studies were based onmicroscopical criteria that could notprovide quantitative measures ofgenetic diversity, these methods rarelyprovided profiles of communitystructures (Edgcomb et al. 2002).The power of molecular techniquesmakes it possible to understand thefunction and composition of terrestrialecosystems. Giovanonni et al. (1990)study marked the advent of thesetechniques to solve purelyoceanographical questions. Bysequencing the 16S ribosomal RNAgene, these authors showed that therewas an unexpected diversity ofbacterial populations in oceanicecosystems and none of thesepopulations corresponded topopulations established in culture atthat time. Later, Urbach et al. (1992)showed that Prochlorococcus marinus,a cyanobacterium recently isolated inculture had in fact a 16S rRNA that wasvery close to certain unknownpopulations of the Pacific and SargassoSea. This study showed thatmetagenomic techniques couldaccount for new taxa before they areever accounted for in culture.Following the footsteps of Urbach, themain part of the data gathered so far ondiversity of eukaryotic communities(including heterotrophic, autotrophicorganisms or mixotrophs) was relatedto oceanic, marine or coastalecosystems (Moon-van der Staay et al.2001a; Mann 2003). These studies haveshown a high level of diversity as wellas new evolutionary lineages in recentyears (Díez et al. 2001; Guillou et al.2002; Massana et al. 2002). Similarly,other metagenomics surveys ofeukaryotic microbial diversity frommarine environments have revealedhigher diversity of eukaryotic algae(Lopez-Garcia et al. 2001; Fuller et al.2006). The characterization ofeukaryotic diversity in hydrothermalvents environments in the Guaymasbasin in the Gulf of California has alsorevealed representatives of previouslyuncharacterized protists, includingearly branching eukaryotic lineages(Edgcomb et al. 2002).The diversity of DNA recovered fromenvironmental samples was distinctlyhigher than classical taxonomicalmethods as shown by denaturinggradient gel electrophoresis (Gabor etal. 2003). These metagenomicapproaches have allowed the wealthyconstruction of environmental genebanks (Gabor et al. 2003).Environmental samples within algalorganisms have shown the extent oftaxonomic diversity in marineenvironments (Díez et al. 2001; LopezGarcia et al. 2001; Moon-van der Stay etal. 2001b), and from freshwater

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 38environments (Sherwood et al. 2008). Astudy conducted by Lawley et al. (2004)demonstrated the usefulness of ametagenomic approach using samplesfrom Antartic soils samples.Sherwood and Presting (2007) havedemonstrated the usefulness of a singlepair of primers that can amplify the 23Splastid rDNA gene of eukaryotic algaland cyanobacterial groups. Thismolecular marker has been successfullyused to identify algal groups from astream in Hawaii (Sherwood et al.2008). However, to our currentknowledge, this is the first subaerialalgal biodiversity study based onenvironmental sequences.Our current research is focusing on thebiodiversity of subaerial algae (Rindi etal. 2010). Subaerial algae are algae thatlive exposed on a variety of substratesabove the soil surface (Graham et al.2009). For an alga, this is an extremelyharsh environment (terrestrial) wherewater plays a major role. As many othersubaerial components, such asterrestrial mosses, liverworts, andhornworts, algae need water tocomplete sexual reproduction byallowing the motile sperm to fertilizethe egg (Raven et al. 2005). Water isalso essential, both as a substrate (inphotosystem II) and as a medium(enzymatic reaction) to performphotosynthesis (Hoganson andBabcock 1997). Rainforests are amongthe wettest ecosystems where waterreaches the habitat either as rainfall oras water vapor (due to high humidity)that is absorbed directly from the air.Thus, humid tropical rainforest areideal habitats for subaerial algae.Tropical rain forests are housing a largeproportion of the world’s biologicaldiversity. However, these forests arevanishing very rapidly compared withother biomes (Laurance 1999; Achardet al. 2002). In Africa, the tropicalrainforests are restricted to theequatorial belt, with its largest block inthe Congo Basin and the lower Guineanarea. This central area is the secondlargest block in the world (Wilkie andLaporte 2001). Within Central Africa’stropical forest, lies the country ofGabon. With almost 80% of its surfacearea covered by the moist tropicalforest, Gabon is one of the mostbiologically diverse countries in allAfrica (Breteler 1996) and highlyamenable for studies on thebiodiversity of subaerial algae.The African tropics were estimated tohave 40,000 to 45,000 plant species(Beentje et al. 1994), among thisdiversity 6,000-10,000 plant species arefound in Gabon (Letouzey 1968). InAugust 2002 a National Park Systemwas created by a Presidential decree inorder to protect the country’s forest.This system has put 10.8% of thecountry’s territory under fullprotection. One of these parks issituated in “les Monts de Cristal” (theCrystal Mountains). The region of “LesMonts de Cristal” is known for itsbotanical richness and is consideredone of the richest in Gabon andprobably in Central Africa (Wilks 1990).Several biologists before have beeninterested in the flora and fauna of thisregion for decades (Reitsma 1988;Gentry 1993; Stévart 2003, 2004).However, the terrestrial algal flora hasbeen overlooked and never assessed inthis region. Considering the high

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 39humidity and habitat diversity found intropical rainforests (Neustupa 2005;Rindi et al. 2006), a Gabonese study isexpected to yield a high diversity ofsubaerial algae.Collection and export permits wereacquired from the “Agence Nationaldes Parcs Nationaux”. Import permitswere obtained from the United StatesDepartment of Agriculture.Algae found in the tropical rainforestare assumed to belong to basicallythree different lineages: Cyanobacteriaor Blue-green algae (Cyanophyta),Diatoms (Stramenopiles), and Greenalgae (Chlorophyta) (Rindi et al. 2010).About 200 subaerial genera founddistributed among these three mainlineages were implicated in previousfloristic studies (Nienow 1996).DNA was extracted from field samplesusing a Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit(Qiagen, Valencia, CA USA) followingthe manufacturer’s recommendations.Metagenomic approaches to the studyof subaerial algae have been absentfrom the literature. In this study, thesubaerial algal community of “LesMonts de Cristal” National Park isevaluated using metagenomics. Thisstudy will provide evidence of therichness and the high biodiversity ofthe subaerial environment as well astest the presence of the three majorgroups of algae found in the subaerialhabitat (diatoms, green, and blue-greenalgae) using environmental cloning.Materials and methodsEpiphytic samples were collected at“Les Monts de Cristal” National Park,Gabon during the rainy season on May20-24, 2008. Algae were scrapped off oftheir substrates using sterile bladesform an area of 4 cm2. Substrates werechosen where evidence of algal growthwas evident (red, green, yellow, or darkareas on different substrates). Sampleswere placed in sterile bags, desiccatedusing sterile silica gel and transferredto the laboratory at the University ofAlabama for further analyses.The PCR primer pair consisted ofP23SrV f1 and P23SrV r1 (Sherwoodand Presting 2007). These primersamplify the chloroplast-encoded 23SrDNA from prokaryotic and eukaryoticalgae. To prevent the amplification ofthe bacterial DNA a touchdown PCRprotocol was used as shown bySherwood and Presting (2007).The amplification of the PCR productswas carried in a thermal cycler (Brand)and the PCR mix consisted of a total of13 µL. The PCR reaction included: 4.4µL of sterile distilled water water; 1.25µL of 10x reaction buffer (AppliedBiosystems California, USA); 1.25 µL ofMgCl2 (25 mM) (Applied BiosystemsCalifornia, USA); 1.25 µL of dATP,dCTP, dGTP, dTTP cocktail (8 mM);0.625 µL of each primer: P23SrV f1 andP23SrV r1 (10mM); 0.1 µL of Taqpolymerase (New England Biolabs,Ipswich, MA). Additionally, we added2.5 µL of 1% non-acetylated bovineserum albumin (BSA) as an additive.BSA has been used as an enhancer ofPCR amplifications when humicsubstances are present. Finally, 1.0 µLof genomic DNA was added to the PCRreaction mix. PCR products were runon a 1% agarose gel with EthidiumBromide to check the integrity,concentration and purity of the DNA. Afragment of about 450 base pairs was

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 310cut from the gel and purified with aQiagen Mini Elute Gel Extraction Kit(Qiagen) following the manufacturer’srecommendations. The resulting DNAwas then ligated into cloning vectorsusing ATOPO-TA Cloning Kit with thePCR 2.1-TOPO Vector (Invitrogen,California, USA) following theirprotocols. After the insertion, plasmidswere transformed into Escherichia coliprovided from the TOPO-TA CloningKit followed by a heat shock with theaddition of S.O.C medium (SuperOptimal broth with Cataboliterepression). Bacteria were transferredto an incubator were they were shaken(200 rpm) at 37 C for one hour.Bacterial cells were then plated onLuria agar plates with Xgal andampicillin. Plates were incubated at 37C for 24 hours followed by a visualinspection to detect colonies withinserts (white colonies). These colonieswere transferred into theaforementioned cocktail PCR and usedas DNA template for the amplification.This time the PCR protocol included aninitial denaturing phase of 5 minutes at95 C, followed by 35 cycles of 94 C for30 seconds, 58 C for 30 seconds and 72C for 30 seconds, with a finalextension of 7 minutes at 72 C. Theresulting samples were run on a 1%agarose gel with Ethidium Bromide,excised from the gel with a sterileblade, and purified with a Qiagen MiniElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen).Resulting DNA was quantified viaNanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer(NanoDrop Technologies, Delaware,USA). DNA products were sequencedwith the same primers in bothdirections using Big Dye version 3.1sequence kit (Applied BiosystemsCalifornia, USA). Following the cyclesequencing reaction DNA wassequenced using an ABI 3100automated sequencer (AppliedBiosystems). Sequences were capturedas text as well as color-codedelectropherograms using Sequencher4.5 (Gene Codes Corporation,Michigan, USA).DNA sequences were aligned in ARB(Ludwig et al. 2004) based on thesecondary structure of the plastidribosome (Cannone et al. 2002). Forcomparison, UPA (Universal PrimerAmplicon) sequences for Cephaleurosvirescens SAG 42.85, Trentepohlia sp.SAG 117.80, and Printzina sp. Panama[F223] were generated following thesame protocols described. Phylogeneticanalyses were carried out based on thecloned sequences. For comparison,UPA trentepohlialean sequences wereadded to the data matrix as well asother representatives of available algalUPA sequences reported previously(Sherwood et al. 2008) and depositedin GenBank.The phylogenetic analysis was carriedout using the Maximum Likelihood(ML) approach on the resulting dataset(Allali 2011) and the phylogeny wasreconstructed using PAUP* 4.0b10(Swofford 1998) using the general timereversible model with a portion ofinvariant sites and gamma distributedrate variation among sites (GTR I Γ)that was determined using Modeltest3.07 (Posada and Crandall 1998). Theresulting tree was processed usingAdobe illustrator for printing andvisualization purposes.

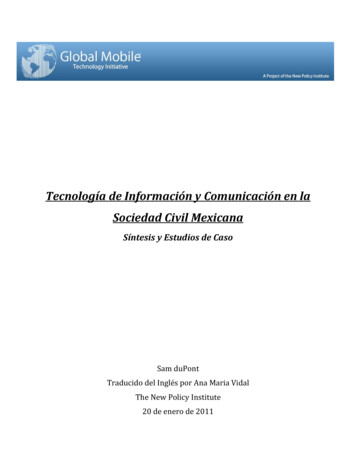

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 311ResultsThe Maximum Likelihood tree (Figure1) illustrates different photosyntheticeukaryotic and prokaryotic organismsas well as non-photosynthetic plastidbearing Apicomplexans. The analysisconsisted of 467 taxa including about150 environmental 23S sequences fromAfrica. The dataset consisted of a totalof 513 characters. There were 60invariant characters. Among the 453variable characters, 361 were parsimonyinformative.The environmental sequences fromAfrica were inferred to four majorlineages: the prokaryotic algaeCyanobacteria, and three othereukaryotic groups the Streptophytes,the Chlorophytes and theStramenopiles. The different colors inthe tree represent the different groupsof algae. Subaerial environmentalsequences (represented by the prefixGA MC ENV#) from Gabon are labeledwith capital letters (see legend).The tree was rooted through the midpoint rooting and the longest branchwas that leading to the Apicomplexansdepicted with the light blue color,following a counterclockwise directionof the Apicomplexans we have theEuglenoids (depicted in yellow color).Adjacent to the Euglenoids we observethe Rhodophytes with the red color,However the Rhodophytes shown hereare non-monophyletic and are split bythe Stramenopiles represented with thebrown color. In the Stramenopiles wefind some of the Gabonese subaerialenvironmental samples (sequenceslabeled S and T). These sequences weremore related to the diatoms than theother Stramenopiles. Movingcounterclockwise from the cluster ofRhodophytes and Stramenopiles wefind the Cyanobacteria (blue-greenalgae) depicted in purple color.Sequences labeled P, Q, and R wereinferred in the cyanobacteria.Cyanobacteria are a monophyleticgroup representing the onlyprokaryotic organisms in thephylogeny. Sequences labeled R weregrouped with Scytonema, whilesequences labeled P were grouped withPhormidium and Microcoleus. Finallycolony 125 (labeled Q) forms a cladewith Anabaena and Nostoc. Adjacent tothe Cyanobacteria we have a cluster ofCryptophytes, Haptophytes, andClaucosystophytes depicted in orange.Moving counterclockwise from thecluster Cryptophytes, Haptophytes,and Claucosytophytes is theStreptophytes clade (the dark greencolor). In this clade we find land plantsand photosynthetic green algae.Environmental sequences in this groupwere spread between Bryophytescommonly called mosses (sequenceslabeled O), the liverworts (sequenceslabeled H, K, and J), Angiosperms(sequences labeled N, M, L), and theTrentepohliales (sequences labeled I).Sister to the Streptophytes is theChlorophytes clade depicted with thelight green color. The Chlorophytesinclude the rest of the green algae.Sequences in this group were inferredto two major lineages theChlorophyceae and theTrebouxiophyceae. Sequences labeledA and B were inferred aschlorophycean grouping withDunaliella, Chlamydomonas, andChlorochoccum. The other sequences(C, D, E, F, and G) were grouped with

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 312PPOOQQRRSTTSNNMMLLKKAAJJIIBBHHGGCDDFFECFigure 1. Maximum likelihood phylogeny of African subaerial epiphytes. The tree shows the majorsubaerial algal constituents (Cyanobacteria, diatoms, and green algae). The letters indicate phylotypesof subaerial algae found in “Les Monts de Cristal”.COLORLight greenDark greenOrangePurpleRedBrownRedYellowLight blueTAXONOMIC laucosytophytaCyanobacteriaRhodophyta (Group 1)StramenophilesRhodophyta (Group 2)EuglenozoaApicomplexaGabonese environmental sequencesA,B,C, D, E, F and GH,I,J,K,L,M,N,ON/AP,Q, and RN/AS and TN/AN/AN/A

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 313the trebouxiophycean generaMicrothamnion, Rosenvingiella,Chlorella, and Prototheca.DiscussionApicomplexans:Depicted as the longest branch of thephylogeny, the Apicomplexans areunicellular parasitic organisms ofanimals and share a remnantchloroplast (the apicoplast) with otheralgae (Moore et al. 2008). Theseunicellular parasites acquired theirapicoplast through secondaryendosymbiosis of a red alga much likethe same way the Dinoflagellatesacquired their plastids (Moore et al.2008). However, due to the parasiticnature of the Apicomplexans, theirapicoplast is non-photosynthetic and isnon-functional. The non-functionalityof the remnant plastid may have lead toless selective pressure on its genomeand may have led it to mutate rapidly(Wilson et al. 1996). This may explainwhy the Apicomplexans representedthe longest branch in the MLphylogeny. Apicomplexan sequenceswere not found among the Africanenvironmental sequences.CyanobacteriaCyanobacteria are photosyntheticprokaryotes that were among the firstorganisms to invade the terrestrialenvironment (Lopez-Bautista et al.2007). Cyanobacteria share the samephotosynthetic pathways as otheralgae, which lead to their classificationwith algae for a long time (blue-greenalgae); however, they were lately placedin the domain Bacteria based on 16SrRNA sequences (Woese et al. 1990). Inthe ML phylogeny (figure 1)Cyanobacteria were among the mostdiverse in the subaerial Africanenvironment based on environmentalsequences. Particularly, Africanphylotypes were inferred to the orderNostocales with genera Scytonema andPhormidium. These genera aremorphologically invested with firmmucilaginous sheaths and they allshare a synapomorphy (the presence ofa heterocyst) (Wilmotte 1994). Becausethe presence of the heterocyst in thesecyanobacteria they are capable of fixingNitrogen (N2) from the atmosphere.These sheathed genera are the secondmost successful group of subaerialalgae after the algae that formsymbiotic associations, and as a groupthey reach their maximumdevelopment in the tropics (Fritsch1907). The Nostocalean cyanobacteriathrive in tropical regions mainly due totwo major factors: first, the frequencyand the abundance of rainfall in thetropics, and second, their ability to fixatmospheric nitrogen (Nienow 1996). Alow concentration of nutrients, such asnitrogen (ammonium and nitrate) inthe terrestrial environment might bethe result of the extensive growth ofthese groups. The subaerialenvironment as opposed to aquaticenvironment is low in Nitrogen (N2),however, the air is composed of 78%N2. The ability of heterocystouscyanobacteria to fix atmosphericnitrogen may give them a selectiveadvantage over other groups of algae.A similar study using metagenomicapproaches conducted by Lam (2010) inSuriname, South America has shownthe presence of cyanobacteria in the

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 314subaerial environment. Previousbiodiversity studies usingmorphological observations haveregularly found these genera in theAfrican tropics (Frémy 1924, 1932;Duvigneaud and Symoens 1948).Viridiplantae:The Viridiplantae (Green plants)include all green algae and land plants,it is comprised of two sister lineagesthe Chlorophytan and the Charophytan(or Streptophytan) lineages. TheChlorophytan lineage comprises theTrebouxiophyceae, the Chlorophyceae,the Ulvophyceae and Prasinophytes (inpart), while the Streptophytan(Charophytan) lineage comprises theCharophyceae, the Prasinophytes (inpart), and land plants (Lewis andMcCourt 2004). The “green plants”along with the Rhodophytes and theGlaucosystophytes share a closerelationship with cyanobacteria.Chlorophytes, Rhodophytes andGlaucophytes evolved a plastidialcondition by primary endosymbiosis.Endosymbiosis theory states that aphotosynthetic cyanobacterium wasengulfed (ingested and retained) by aheterotrophic protist (Delwiche 1999).Our environmental sequences fromGabon, Africa inferred the followinggroups to be members of the subaerialcommunity in “Les Monts de Cristal”:the Chlorophyceae, theTrebouxiophyceae, the Ulvophyceae(represented by Trentepohlialean taxa),and some land plants. The presence ofthese groups in this environment wasnot surprising since p

Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología No. 3 5 EDITORIAL Con el tercer número del Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ficología se inicia una etapa distinta para esta publicación. Por dos años será también el Boletín informativo de la Sociedad Ficológica de América Latina y el Caribe. Y es momento para rendir un homenaje a