Transcription

5Ann Berry SomersManaging Wetland VegetationRound-leafed sundew (Drosera rotundifolia).

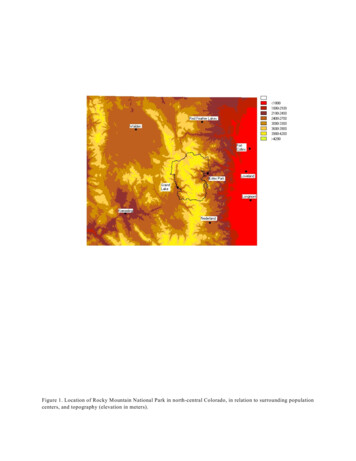

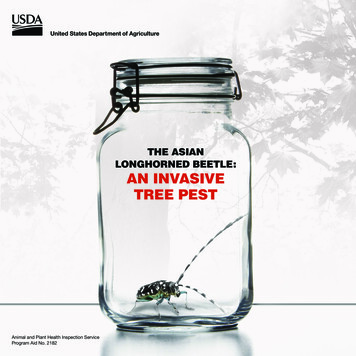

CHAPTER FIVEManaging Wetland VegetationThe purpose of this manual is to assist landmanagers in becoming successful wetlandmanagers. A land manager can be any personor agency aware of the special needs and benefits of wetlands who has the power to makethe needed changes. The intent is to stop thedecline of wetland plants and animals byproducing more and better wetland habitats.Habitats are environments used by species togrow, live, hibernate, bask, forage, and reproduce. The management options for specificwetlands vary, based on site character and theobjectives and motivations of the managementplan. Discussed below are some techniquesused to manage wetland vegetation. While theprimary consideration should be to improvethe function of a target wetland, the adage“first, do no harm” is also worth remembering.Over time, freshwater wetlands in theSoutheast succeed toward a closed forestcanopy; the sunny microhabitats graduallydisappear as the interior surface becomesshady. The time this takes can be relativelyshort. For example, the Southeast experiencedvery dry conditions in the mid-1980s andduring this time extensive woody growthemerged in many wetland sites. Although it isdifficult to predict how global climate changewill impact the wetland hydrology and biotaof the Southeast, clearly the succession toshaded conditions is an important consideration in the conservation and management ofsmall wetlands.Many plants and animals require opensunny habitats and are not found in heavilyshaded areas. Appropriate treatments may beneeded to manipulate the wetland communitiesto the desired mix of woody and non-woodyplants. For example, the ecology of the bogturtle seems to indicate a preference for patchyhabitat of wet shrubby and woody areasinterspersed with open, sunlit, boggy, wetmeadows with various herbaceous vegetationtypes (Box 5.1). This habitat type might havedeveloped and been maintained by naturaldisturbances (high winds, storms, floods) andthe actions of animal herbivores such as beaver(Castor canadensis), elk (Cervus elaphus), or bison(Bison bison). Of the types of animals thatmight have played an important role, thebeaver is the most likely since it not only feedson woody plants, but is also an accomplishedwetland builder. In many cases, our management strategy might be guided by comparisonwith the actions of beavers on the nativelandscape (see Wetland Management byBeavers, Chapter 6).Several options for managing woodywetland vegetation include cutting, grazing,chemical methods (herbicides), and the use offire. Each site will present prospects andchallenges for the use of any or all of thesetechniques. Also, new technology and greaterexperience will likely produce new techniquesapplicable to specific problems. This basicdiscussion of vegetation management considersthe dynamics of wetlands, the ecology ofwetland species, and the larger picture of thewatershed. With so many wetland functionsand values at risk, it is helpful to know thatoptions exist for their restoration andmanagement.Mechanical Woody VegetationRemoval TechniquesAs used here the term mechanical meanscutting, sawing, clipping, mowing, uprooting,and related physical techniques that can beused directly on plants. A variety of toolsand mechanical equipment may be used tocut back or pull out wetland woody plants,depending on the job required. The size ofthe wetland and the amount of management47

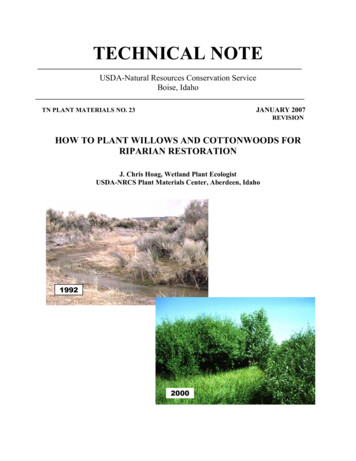

CHAPTER FIVEManaging Wetland VegetationBox 5.1 Removal of Hardwood Canopy is Beneficial to the Bog TurtleBy Dennis W. HermanDennis W. HermanThe bog turtle’s ultimate enemy may be a closedcanopy. The turtle’s basking sites and nesting areasare located in open, sunny sedge meadows withemergent vegetation and a subcanopy of shrubs.Later stages of succession produce a closed canopythat blocks sunlight and eliminates surface warmingand herbs. Bog turtles are long-lived, reaching agesin excess of 40 years. Mating and egg-laying canoccur over the life of a bog turtle. Reproductivesuccess declines as adequate nesting sitesdisappear and individual turtles can live to a ripe oldage persisting in sub-optimum sites. If areas open upDennis W. HermanThis view of a meadow bog shows how livestockgrazing maintains the open, shrubless wetlandspreferred by bog turtles.A view of the same meadow bog showing the rapidshrub succession two years after livestock wereremoved. Habitat becomes less suitable for bogturtles as shade increases.48in the wetland by man-made or natural reasons, thenreproduction can once again occur in the population.This case study illustrates how an aged population ofbog turtles benefited from the removal of canopyspecies and actually began reproducing again afternearly two decades.The bog turtle was discovered along a secondorder stream in a north Georgia county in 1979. Thehabitat where the first turtles were found was atypical,comprised of a rocky meandering stream with smallseepages irregularly located along the stream.Some typical wetland species were observed in theseepages including sedges (Carex sp.), bog rushes(Scirpus sp. and Juncus sp.), and small amounts ofpeat moss (Sphagnum sp.). A hardwood canopy ofoaks (Quercus sp.), maples (Acer sp.), and tuliptree(Liriodendron tulipifera) dominated the area preventingsunlight from reaching the forest floor.A bog turtle survey began in 1979 by a US ForestService biologist ended in 1982. Only one old adultfemale was found during this initial survey. Dr. KenFahey found additional adult bog turtles from 1983to 1986, all of them very old. No evidence ofreproduction was ever found at this site, and it wasassumed that it was an old population, expected topersist only until the last turtle died out.The upper slope above the site was logged in1986, but provided no direct benefits to the population.The survey was discontinued from 1987 through 1990.In 1990, Dr. Fahey and the US Forest Service joinedforces, renewed searches, and began a trappingcampaign to locate new turtles. The survey wasmoderately successful, with the capture of additionalspecimens, yet reproduction and recruitment were notobserved. The Forest Service, at the urging of Dr.Fahey, began to selectively remove some vegetationand girdled some large trees in 1993. Girdling of treeshas continued from 1994 to the present. A bog turtlenest containing three eggs was found in the top of arotting hardwood stump in July 1997 in one of theopen areas created by tree and vegetation removal.This was the first reported case of bog turtlesreproducing at the site and in Georgia.

CHAPTER FIVErequired to implement the plan oftendetermine the most effective and efficientmethod to use. Small wetlands, like the mostcommon ephemeral pools, seeps, and bogsare amenable to skillful management bypeople using hand tools without the aid oflarge, heavy machines. On the other hand,large areas like floodplain forests may requirelarge equipment like trucks, tractors, andearthmoving equipment to achieve themanagement goals. If heavy equipment wasused to drain or otherwise alter the wetland,then it is likely that similar equipment willbe required for restoration.The amount of time required for differenttechniques also needs consideration. Canorganized work crews of volunteers be usedat the site? Is there sufficient skilled laboravailable from the landowner or other localgroups to do the job? Can someone subcontractthis work? Who has the knowledge and skills?The timing of the treatments and the frequencyof repeated or subsequent treatments must beconsidered. Does the management plan outlineany alternative treatment options as conditionschange? How will the treatments and subsequent responses be evaluated for effectiveness?A wetland management project where the goalis to keep conditions sunny will require moreintensive management practices. Considerationmust be given to the fact that managementmight also continue far into the future andplans should be made now to ensure that thebest possible arrangements have been made forthis commitment.Choice of technique may depend on theseason in which the work will take place. If awetland has deep, soft mud, as required by bogturtles, this condition will limit the machineryused and may make it difficult to walk aroundthe site even in high boots. The impact ofentering a wetland, with either machinery orpeople intent on drastically modifying thevegetation, should not be considered a trivialpart of the management project. In some casesthe trampling, crushing, and breaking of thesurface and the hummock forming vegetationcan cause direct destruction of plants, eggs,nests, or animals who hide in these niches.Matt FlintManaging Wetland SitesTurk's-cap lily (Lilium superbum) is found in moistconditions in the Mountains.This damage can affect reptiles, amphibians,mammals, and invertebrates that live and nestin the low vegetation at the open margins ofwetlands. Excessive trampling may also harmthe hydrology of the wetland by penetratingimpervious soil layers.Careful cutting of wetland woody treesand shrubs can be effective in opening a closedcanopy to the point of producing a response inthe plant community. Often it might be helpfulto experiment on a small part of the wetland todetermine both the logistics of the site and togauge the response of the treatment before it iswidely applied. Cutting with hand tools orhand-held power equipment is the mostaccurate method of trimming or removingwoody plants. Removing individual plants toopen the canopy and allow more light to reachthe surface can benefit surface basking reptiles,amphibians, and insects. These openings inthe canopy may also benefit wetland herbsrequiring sunlight at the surface to germinateand grow.There can also be drawbacks to suddennew openings in the canopy. In experimentsto study the effects of canopy openings onpopulations of mountain sweet pitcher plant(Sarracenia rubra ssp. jonesii), it has beenobserved that grasses and even red mapleseedlings aggres-sively colonize some newopenings. In some cases the new plants49

CHAPTER FIVEManaging Wetland VegetationBox 5.2 A DOT Wetland Mitigation SiteBy Kenneth A. Bridle, Ph.D. and Ann Berry SomersDennis W. HermanMitigation is a term used to describe actions tocompensate for environmental damage. This essaydescribes the case of a small wetland restoration andpreservation that resulted as part of a mitigationagreement. This site was chosen because it isconsidered to be a freshwater biodiversity site of localsignificance. The wetland is located in a larger floodplainand was purchased by the North Carolina Department ofTransportation (NCDOT) as mitigation for wetlanddamage during the construction of a highway bypass.The construction project and this wetland are in the sameUSGS hydrologic unit.This wetland, called a “marsh” by locals, consists of arich and diverse biological community in the midst of anhistoric farming and grazing bottomland. Horses andcows have grazed the site as recently as 6-7 years ago.Historic photographs confirm that this wetland has beenexposed to row crops and other agricultural activity sinceat least 1940.Marsh prior to restoration. Note woody growth in backgroundresulting from elimination of cattle and horses that oncegrazed the area.50Possibly the most significant natural area in thecounty, this wetland has been noted by local naturalists,birders, and herpetologists for over 30 years. An informalgroup of biologists has been studying the site withoccasional visits since about 1971. An array of wildlifestudies have been conducted and information about birds,reptiles, and plants all indicate the special biologicalnature of this wetland. Vegetational analysis and soilsurveys were used to delineate the wetland, and sitehydrology was monitored for a year prior to construction.The marsh is composed of at least four separatewetland zones including different assemblages of plantspecies. There is some uncertainty about classification ofthese communities, given their long history of human andagricultural disturbance and natural dynamics. Among thenames applied to the existing plant assemblages by thosewho have been there, are Piedmont Fen or Meadow Bog,Wet Meadow, Marsh Hibiscus Pool and a Boggy AlderThicket. There is also a willow and birch lined ditch and alarge, tree-covered clay pan which functions like anextended ephemeral pool. Each aspect of these areasoffers a variety of wildlife habitat based on the diversity ofplant species and water quality.Present are zones of shrubs such as buttonbush(Cephalanthus occidentalis), swamp rose mallow(Hibiscus moscheutos) and tag alder (Alnus serrulata).Woody plants scattered throughout include silky dogwood(Cornus amomum), swamp rose (Rosa palustris), and thenon-native multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). Herbdominated zones include sedges (Carex spp.) andgrasses, American bur-reed (Sparganium americanum),and cattail (Typha latifolia). Other herbs scatteredthroughout include monkeyflower (Mimulus ringens), lamprush (Juncus effusus), arrowleaf tearthumb (Polygonumsaggitatum), swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata),orange touch-me-not (Impatiens capensis), white vervain(Verbena urticifolia), and a hedge hyssop (Gratiola sp.).Drier areas support ironweed (Veronia noveboracensis),

CHAPTER FIVEtick trefoil (Desmodium sp.), and grasses such as redtop(Agrostis stolonifera), fescue (Festuca sp.), and timothy(Phleum pratense).The mitigation plan included a 40 acre buffer ofold fields around the wetland site. Key to the projectsuccess may be these enhancements, which restoredadditional parts of this floodplain to a wetland condition,increasing its value as a functional and biodiversewetland. Ditches were filled, two more pools wereexcavated, and raised berms and a freeboard dam wereconstructed to control water levels in the area.Continued monitoring of the plant communitydevelopment and hydrology are taking place in restoredareas now that the construction phase is completed.On-going threats to the site are primarily a result ofthe nearby human population. The major threat to waterquality is fertilizer runoff from nearby develop-ments,and buffers have been constructed to help absorb someof the excess. The primary animal threats to wildlife arefrom free-ranging domestic cats and an apparent overabundance of raccoons. Cats hunt wildlife even if theyare well fed at home. Raccoons proliferate as a result offree food offered by humans in the form of garbage,compost piles, and pet food left on porches. Thesepredators endanger the eggs, young, and adults of mostreptiles found in the site; the eggs and chicks of groundnesting birds; and almost all other small animals.Biologists’ recommendations for thesite include management for these pest species. Theymenace many conservation initiatives throughouteastern North America.SITE SIGNIFICANCE: Regionally significant dueto the size of the wetland, the complexity of its naturalcommunities, and the presence of at least one specieslisted as threatened and several uncommon species.PROTECTION STATUS: Easements, managementplan, and transfer of the land to a qualified conservationorganization after the NCDOT mitigation requirementsare fulfilled, will accomplish long-term protection.Ann Berry SomersManaging Wetland VegetationBeavers kill large trees by girdling them, eliminatingpatches of canopy. This technique also works well whenused by humans to limit shading.colonize so thickly that other plants areexcluded, including the rare pitcher plant.Plants can be topped, limbed, or cut backto the ground in order to make openings.However, this treatment often may cause abushy regrowth. Felling of large trees can alsohave a literal impact, depending on what theyhit when they fall. Another method, barkgirdling, removes the bark cutting off nutrientsupplies to the roots, resulting in the death ofthe tree while leaving it standing as a snag.Standing dead snags can provide additionalhabitat for many species for many years.Eventually the tree will fall and provideimportant habitat and cover for animals andother species. Girdling is an easy, effective,and selective technique that can cheaply killwoody species using simple tools.Managing Woody DebrisCutting techniques generate lots of debris,which may also need to be managed. In somecases this accumulation must be removed fromthe wet region, and may be used to createnearby brush piles for animal habitat. Anotheruse for this material may be within the wet51

CHAPTER FIVEManaging Wetland Vegetationcore area —by placing it as a beaver might tomake low dams perpendicular to the slope ofthe valley. These structures slow down theflow of water and spread the flows into sheetsacross the ground surface. They also increasethe ability of the wetland to filter and trapsediments, capturing material to increase theorganic material retention. They can be usedin conjunction with other methods to increaseretention of water in the site (see Chapter 6).If these structures are effective in altering thesurface hydrology, this modification mayincrease the wetness of the site and might alsohelp modify surrounding vegetation for thebenefit of wetland species like pitcher plants.Excessive flooding may occur during springtime or other wet periods and should beavoided, as it may drown eggs or otherwiseharm some wetland species.Mowing and Using Heavy EquipmentOn those sites where it is deemed appropriate to use heavy equipment to fell andremove trees or mow down herbs and brush,care must be taken to minimize the adverseimpacts of this type of work. Not only thephysical impact of the equipment, intentionaland incidental, but also the probability of fueland oil spills, and other contamination must beexpected and planned for. It is important thatthe equipment operator be aware of management goals or work under close supervision.Box 5.3 Woody VegetationCutting Suggestions With the help of a professional, assesswhat to cut based on the desiredoutcome. Use the least impact method possible. Limit canopy removal to 25-50 percentper year. Plan to use or manage the cuttings. Avoid stepping on hummocks and otherareas where hatchlings or eggs couldbe disturbed. Disturb only one patch of the site at atime. Assess the impact before continuing.52In many cases a skilled equipment operatorcan use experience and finesse to augmentthe plan and make necessary corrections oncework has started. Do not leave an operatorunsupervised as most equipment can make adramatic impact quickly, and some mistakesare uncorrectable.Many agricultural techniques like mowingand haying can also be used to manage vegetation in and around wetland sites. The timingof any vegetation management operationshould be such that no harm is done to nativespecies of plants and animals encouraged bythe wetland management plan. Care should betaken to avoid cutting pastures too low, whichcan damage nests, kill small animals, and scalptufting, clumping, and climbing vegetation.Consultations with local biologists and wildlifemanagers can be used to plan the best timeand frequency of cutting, mowing, or hayingoperations. Slight alterations in typical farmactivities can profoundly impact a wetland andits native communities. Delaying mowing justa few weeks or leaving an unmowed area as abuffer and refuge, may only slightly affectfarm operations, but may be critical to aflowering or nesting species’ reproductivesuccess for the year.Horse logging, a technology of a past era,is regaining favor for use in conditions whereenvironmental impact from standard equipment is a concern. Horses can get into tighterareas with less surface stability than wheeledequipment. Horses can also disturb the surfaceless during log skidding. Horse hoof prints alsodo not channel water flow in the same way astire ruts which can dramatically change the waysurface water flows.Grazing and BrowsingAnimals as a Means ofVegetation ControlMany types of animals make their homesin native wetland communities, living off theproductivity of the plant communities in aparticular area. Commonly, large animals likedeer and beaver can crop woody vegetationenough to have a dramatic impact. Other

CHAPTER FIVEManaging Wetland VegetationBox 5.4 Mowing andHeavy Equipment Use Suggestions Use the least impact method possible. When mowing, don’t cut close. Don’t mow more than once a year, lessoften if possible. Unmowed grassy andweedy areas provide important refuges andforaging areas for many forms of wildlife,including various game species, songbirds,and butterflies. Minimize ruts and compaction of soilsand vegetation. Plan to minimize and mitigate fuel, oil, andgrease contamination in the site. Avoid working during known breeding timesand in suspected breeding places. Limit canopy removal to 25-50 percentper year. If using heavy equipment, disturb only onepatch of the site at a time. Assess theimpact before continuing.animals like small mammals, insects, and birdscan have an equally impressive impact onnative plant communities by eating vegetation,pollination, seed dispersal, and other activities.As the biodiversity of the wetland restorationincreases, many more levels of structure andinteraction become evident.Animals can be one of the most effectiveand important means of controlling unwantedvegetation by their grazing, browsing, barkstripping, root eating, and other woodyvegetation manipulations. While someanimals graze fresh succulent new growth,others gnaw at bark and, in the case ofbeavers, even fell sizable trees. Commonlarge animals, like cows, horses, goats, andsheep, can keep vegetation well trimmed inany paddock. These and other agriculturallyimportant farm animals have been used asvegetation management tools for centuries.Livestock GrazingBenefits derived from limited grazinginclude retardation of woody vegetation andshrubs, and prevention of channel formation.Hooves break up the rootstocks of shrubs andallow sheet flow to be restored. When livestock are removed from wetlands, water nolonger pools in hoof prints, channels appear,and water flowing out of the site is increased.This enhanced flow in channels can cut deepgrooves into the soil, increasing the detrimentaleffects of water lost to the system. Besidesinhibiting channel formation, hoof prints alsoprovide hiding areas for bog turtles and otherwetland animals and exposes mineral soilfor seed germination. However, excessivenumbers of livestock can create problems bydenuding vegetation and increasing nutrientinput from fecal droppings.At one time many conservationists thoughtthat removing grazers was important for manyrare wetland species populations to persist.In light of recent studies however, cattle andother livestock are now considered vital inmaintaining site suitability for bog turtles andother rare species. The benefits derived fromgrazing can far outweigh negative impactssuch as accidental trampling of plants andanimals, compaction of soil, and additionalnutrient enrichment.A flexible system with the capacity tomove animals into and out of the wetland,or provide grazer access only at specifiedtimes of the year will be the most useful andpotentially the most agriculturally productive.Paddock management, fencing, alternativewatering sources, heavy use areas, andcontrolled wallows have proved to be positiveinvestments in many streamside and wetlandsites—benefiting both the farmer’s businessand the environment of the watershed. Theseare practices where the strength of conservation agencies can help landowners withnew technical information and financialassistance (see Chapter 7).The best grazers for promotion of bogturtle habitat appear to be beef cattle; goats orsheep may have similar or perhaps greaterbenefits, but these have not been studied.Limiting grazing density to no more than oneanimal unit ( one mature beef cow, also seeGlossary) per acre will optimize the situationfor both pasture health and turtle success.53

CHAPTER FIVEKenneth A. BridleManaging Wetland VegetationManaging wetlands may include seasonal exclusionof livestock.Adjustments can be made when other types ofgrazers, such as dairy cattle, horses, or sheep,are involved. Once a grazing regime isin place it can be fine-tuned by removing oradding livestock to the site.The use of excluder fencing and seasonalgrazing (winter grazing) are important conservation tools for the management and protectionof bog turtle and other wetland species habitats.Seasonal exclusion of cattle has been proven tobe an effective management tool in regulatingBox 5.5 Wetland Grazing Suggestions Allow only light to moderate grazing. Beef cattle are the preferred grazer; buthorses are also highly effective. Goats andsheep may also have important beneficialeffects. A ratio of 1 animal unit per acre is preferred. Grazing on a seasonal (winter only) rotationbasis is acceptable. Construct a fencearound the site allowing a buffer of nativevegetation to filter polluted runoff. Use fertilizer and lime sparingly whenapplying to lawns and fields surroundingany wetland. Use excluder fencing around known orsuspected turtle nesting areas, sensitiveplants or plant colonies.54soil and vegetation impact: denuded areasbecome reestablished with vegetation, sensitive plants can grow, and safer conditionsexist for wetland nesting animals. Cattle canbe permitted free access to the wetland duringlate fall and winter, permitting the benefitsdescribed above. Researchers studying adangerously small population of bog turtles inNorth Carolina recorded a population increaseof 85% within a 5-year period after seasonallyrestricting cattle. Other strategies includeallowing grazers access to the sites yearround, but drastically limiting their numbers.Protection of nesting areas is paramount tothe success of turtle populations.Although bog turtles and some other rarespecies do indeed coexist with wild anddomestic grazers, some plants cannot tolerateinteraction with livestock. The size and typeof wetland community have to be correctlymatched with the amount and type of grazingin order to limit negative impacts on thewetland natural communities.Chemical Controls ofVegetationThe modern tools of vegetation controlinclude herbicide chemicals. In any vegetationmanagement project, questions will alwaysarise regarding the advisability of chemicalherbicides for the control or elimination ofundesirable plants. Chemical herbicides arecomplex formulations mixed to meet specificgoals in specific situations. Because of thecomplexity of testing, labeling, and use, mostherbicides are targeted for major markets, likeagriculture, lawn care, or terrestrial weed control.Using Chemicals with CautionEach year chemicals are released into theenvironment in many forms ranging from rawpetroleum products to refined pharmaceuticals.These chemicals amount to billions of poundseach year. The fates of these chemicals and thelife cycle of their products in the environmentare largely unknown. The release into theenvironment of chemicals commonly known

CHAPTER FIVEManaging Wetland Vegetationas pesticides can be especially risky as they aredesigned to be toxic. When deciding to usepesticides, one must consider the balancebetween benefit and risk. Herbicides are atype of pesticide used to kill plants.Registration of herbicides follows acomplex set of rules that seek to allow the saleand use of chemicals judged to produce morebenefit than harm. However, out of alltheoretical possibilities, it is only possibleto research the likely and obvious uses ofchemicals. Therefore the labels of herbicidesare specific about how they can and should beused. Use of any herbicide in a manner notintended on the label is illegal and bothpersonally and environmentally risky. Becauseof the relatively small amount of applicationsof herbicides in and around water and thecomplexity of adding chemicals to aquaticsolutions, few herbicides are labeled for use inaquatic or wetland conditions.Testing for labeling includes herbicidetoxicity in several types of models: breakdownproducts, persistence in the environment,potential to accumulate in the food chain, andhazards to non-target species. This complexassessment allows chemical manufacturers toclaim benefits as weighed against potentialand documented risks. Few chemicals havebeen tested with rigor for their impact on theenvironment, including unintentional consequences to non-target organisms and humans.Many chemicals can and do react to formcomplexes of products, most of which havenot been well-studied. The interactions andaccumulation of these products and theirunintended consequences have, however, beendocumented with a few now famous casestudies of DDT and 2,4 D effects on wildlife.Caution in the use of herbicides is alwaysrecommended. It is therefore crucial to applyherbicides according to label recommendations.There may be conditions in wetlandswhere concerns for the effectiveness andefficiency of plant growth control offsetunintended impacts of chemical herbicides.In these situations the selection of the properchemical, application, timing, and techniquecan reduce negative impacts as well asenhance effectiveness.At the time of development of yourmanagement plan, a review of the availablelabeled herbicides should be undertaken.Labels and chemical formulations change asolder compounds are replaced with newerformulations for new uses. It is often best tocheck with the local cooperative extensionagent to get an update on what might beavailable to achieve the intended goals forchemical vegetation control. Names andproduct descriptions given in Appendix G arefor discussion and are not intended asendorsements.Application TechniquesHerbicides are typically applied as sprays,liquid paints, injections, granular formulations,or fumigants. There are no granular formulated products or fumigants appropriate orlabeled for wetland conditions. Some of thesemight be used in adjacent crops and t

used and may make it difficult to walk around the site even in high boots. The impact of entering a wetland, with either machinery or people intent on drastically modifying the vegetation, should not be considered a trivial part of the management project. In some cases the trampling, crushing, and breaking of the surface and the hummock forming .