Transcription

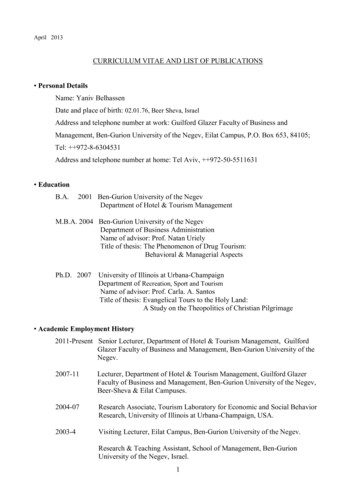

ElGenogramsPractical tools forfamiy physiciansIAN WATERS, MSW, CSWWILLIAM WATSON, MD, CCFPWILLIAM WETZEL, MSWGENOGRAM IS A VERSATILEclinical tool that can helpfamily physicians integrate a patient's familyinformation into the medical problem-solving process for betterpatient care. Physicians in primary careoften have to treat patients with seriousmedical illnesses (eg, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension) in combination with psychosocial problems(eg, domestic violence, substance abuse,relationship difficulties). Knowledge ofboth biomedical and psychosocial issuesis needed to diagnose and manage thesepatients. The family genogram (familytree) offers a unique opportunity forobtaining family medical and social history from patients more easily, and forexpanding a family physician's understanding of the presenting problems byproviding a quick picture of the contextin which they occur.SUMMARYA geogram can help a physidanietegrate a patient's familyinformation into the medicalproMmn-solving process forletter patient care. A genogramallows a physid. to obtimmedicol and psychosodalinformation from . patinteasily aid, as a result, to have ahifer understanding of thecontext of the presentingsymptoms.RESUMELe g6nogromme est n outilqui penmet au m6dedn demieux int6grer les donneesfamliales du patient dons leprocessus m6dKald solutionde problimes, donc d'am6liorerla qualite des soins. Grace auMr Waters is a Social Worker and Lecturer;Dr Watson, a Fellow ofthe College, is anAssistant Professor, and Mr Wetzel is a SocialWorker and Lecturer in the Department of Familyand Community Medicine at the University ofToronto. Mr Waters is on staff at The TorontoHospital. Dr Watson and Mr Wetzel are atSt Michael's Hospital. They are all members ofthe Working with Families Institute at theUniversity of Toronto.genoromme, le midecn pautfadlement obtenir losinformations miicales etpsychosodales, ce qu facilerala comprfieslon du contextedes symptomes de presentotien.C mFH1994;4,082-287.I282Canadian Family Physician VOL 40: Februay 1994Family systems medicineDuring the last decade, research hasdemonstrated a relationship betweenfamily functioning and the physical andemotional well-being of an individualpatient.' Family systems medicine haspromoted a family orientation to patientcare by developing several assessmenttools that incorporate both family andpsychosocial information into medicalcare. These family assessment toolsinclude the family APGAR, family circlemethod,2 genogram,3 PRACTICE,4 andFIRO5 models.Physicians using a family systemsmedicine orientation have found thatcreating a diagram of a family's healthcare problems assists them in managingmany of their patients' health care concerns. Genograms have been comparedto more traditional medical tools, such asx-ray films and cardiograms, that helpfacilitate hypothesis generation, differential diagnoses, and ultimately a management plan for the patient.6 "Thegenogram can be thought of as an x-rayofthe family. It gives the physician andthe patient a graphic display of the family, including the family's patterns of illness and psychosocial problems."7Construcing a genogramSymbols for genograms have been standardized, enabling physicians to build a

X .picture of family structure quickly and seehow it affects a patient's ability to copewith illness or other significant life stressors (Figure 1).6 A genogram collects andrecords three generations of family information in six specific categories:* family structure;* life cycle stage;* pattern repetition across generations;* life events and family functioning;* relationship patterns and triangles; and* family balance and imbalance.A8-0During the first visit with complex families, a genogram is best limited to onlytwo generations, or to only family members with significant health problems.Missing family data can be added later ifnecessary. Family physicians should consider completing expanded genogramswhen confronted with patients or familieswith difficult clinical problems (Table 1).Expanded genograms focus on three-generational relationship patterns and usuallytake 20 to 30 minutes to complete.3'7'9Physicians wanting to adopt a family systems orientation to patient care will oftenstart with a basic, or "skeletal," genogram.Completing a skeletal genogram with a newpatient is frequently an effective way todevelop baseline data on who the otherfamily members are, who lives at home,what this patient's context is, and what thefamily's patterns of illness are. The skeletalgenogram takes 5 to 20 minutes to completeand is limited to questions of family structure, significant family events, and history offamily health problems. Often a skeletalgenogram can be completed while recording a traditional family history.BenefitsThe information recorded in genogramsassists family physicians to generatehypotheses about patients' risks for familyrelated illnesses or stressors, such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary heartdisease, substance abuse, and depression.A family history of these problems oftenallows a family physician to generate ahypothesis about a patient's presentingcomplaint quickly and then develop questions that help in coming to a diagnosisand management plan.6 For example, fora patient with gastric complaints, agenogram that indicates a strong familyTable 1. Issues for whichgenograms might behelpfulBIOPSYCHOSOCIAL ISSUES* Anxiety, depression, orpanic attacks* Substance abuse* Multiple somatic orvague complaints* NoncompliancePSYCHOSOCIAL ISSUES* History of physical, sexual,or emotional abuse* Childhood behaviourproblems* Difficult life cycle transitionDOCTOR-PATIENT ISSUES* Angry or demandingpatient* Patient whomphysician dislikesCanadian Family Physician VOL 40: Februagy 1994283

Figure 2. NuaLaK.'. gpatrem: lpat cormpaind fsh.pn mb.,mhpI'kI'Ls.ikGro.RomeFamily history of lcoholism;P*atient.s conffiu6relationship with her father;* Recent separation fti rboyfizend;imitedsupport jts(e& -family and friends); anda Patient's stomach problemnswere likely a combination ofher ncreased ol4 J oand her intern Iizaon ofL1.J W36lstress.Case 1. The following case study and accompanying genogram were taken from Dr William Watson's practice.first met Nuala on a busy afternoon,after she was referred urgently by hersister who worked as an emergency roomnurse at the local hospital. Her sister saidonly that she was having lots of stomachproblems and was under a lot of stress.When I met this 38-year-old woman, shelooked depressed and tired with slightlybloodshot eyes.When asked why she was coming to seeme, she said somewhat angrily, "I've beento see three doctors so far and none ofthem could help me with this stomachproblem." I suspected at that point thatshe might be a difficult patient. She complained of dyspepsia symptoms includingheartburn, bloating, and epigastric discomfort for the past 6 weeks. She had nonocturnal pain or melena. She had triedantacids with no relief. When asked whatshe thought was causing her symptoms,she said she thought it might be an ulcer. Iasked her about alcohol intake and sheindicated that she had increased from twoto three drinks a day. She also stated thatshe smoked 20 cigarettes a day. At thispoint she became very impatient, sayingshe had to get back to work. As herI284Canadian Family Physician VOL 40: February 1994physical examination was normal,I prescribed an H2-receptor blocker andasked her to return in 2 weeks.When she returned I asked her whethershe had any stressors in her life. Sheacknowledged it had been difficult for herrecently. She also stated that her stomachfelt much better, and she seemed lessangry. I asked, "Do you think there couldbe a connection between your stomachproblems and some of the stresses in yourlife?" She then related how she had broken up with her boyfriend 6 weeks agoand had subsequently increased her alcohol intake. She appeared upset about thisand seemed on the verge of tears. Shewent on to talk about how stressful herwork had been lately. With the information on excessive alcohol intake, dyspepsia, and smoking coupled with ademanding, stressed patient, I decided toconstruct a genogram to gain a betterunderstanding of family health issues andrelationships.Nuala talked about her alcoholic father,whom she hated for constantly beratingher mother and herself. She denied anyphysical or sexual abuse. She describedher mothermeek and passive. Both"Well,Nuala," I said, "Sometimes these experiences can affect us in ways that we don'tunderstand. It seems that people whohave lived in families like yours often havepains that doctors cannot completely fix.Perhaps your pain is somehow connectedto your past." I"Could be," she said.I then completed her examination andreviewed her blood test results, whichshowed a mild elevation of liver enzymes.I suggested that she would have to stop herexcessive alcohol intake if she ever wantedto get better. I mentioned some options fortreatment and suggested she return in3 weeks for a follow-up visit.On the third visit, she looked more atease and healthier. She said she hadthought a lot about what we discussed onthe last visit, especially with regard to herfamily. She recognized some patterns ofalcohol overuse, especially in her grandparents, father, and brother. She thoughtthat she would seriously like to explorealcohol treatment programs and alsoobtain counseling for her stress problems.asparents died several years ago.

history of alcoholism would lead to a highindex of suspicion about the possible roleof alcohol. Genograms can also be effective for evaluating the problems of patientswith multiple vague complaints.By doing a genogram with Nuala(Figure 2), I was able to enhance our rapport. Often demanding, difficult, and angrypatients, as well as patients whom physicians dislike, respond well to being involvedin completing their genograms. Thegenogram process frequently lets patientsand physicians escape from what feels likean unproductive relationship. Patientsinterpret the genogram process as an act ofbeing listened to and cared about as people.The process permits physicians to learnmore about patients' life experiences, and asa result, to be more empathic to patients'needs and behaviours (Figure 3). The newinsight and empathy can in turn be used tofacilitate a more effective and satisfying doctor-patient relationship for both patient andphysician. The increased rapport oftenmeans patients are more open and acceptingof both medical and nonmedical referrals.Completing a genogram also communicates a message to a patient that a family physician is interested in addressingfamily and psychosocial problems as partof ongoing health care. Many patients andphysicians find the genogram a nonthreatening way of inquiring about potentiallysensitive issues, such as sexual abuse andalcoholism.7"2The visual impact of genograms canalso be useful for both physicians andpatients in determining whether presentingmedical problems are connected to familyor psychosocial issues. Family physicianscan quickly look at complex medical andrelational genograms and understand howfamily information could affect patients'presenting complaints. On the other hand,patients are often struck by recurring patterns in their families, such as alcoholismand cardiac problems. This informationcan influence patients' awareness, and foster a sense of urgency to deal with andmake decisions about complying with suggested medical regimens (Table 28).9Potential roadblocks to usinggenogramsThe main concern expressed by familyphysicians is the length of time it takes tocomplete a genogram. Some family physicians consider genograms to be impractical in a busy office practice because theyincrease the amount of time spent on thefamily history section of the office visit.'3Family physicians who have successfullyintegrated genograms into their practicesacknowledge that the genogram processincreases the length of visits. However, theyalso believe that the extra time required isoften well spent building patient rapport orproviding potentially useful family information that can be used to address apatient's concerns during a particularoffice visit or at some future visit.It is also important to note that agenogram is rarely completed in one officevisit and is often constructed with a patientover tirne. For example, many physiciansconstruct a skeletal genogram when theyfirst meet a patient, and then expand itwhen indicated. Often, the genogram iskept in a special place in the chart(eg, attached to the back) so that it can beeasily located, and therefore referred toand built upon repeatedly.The other criticism of genograms isthat, to date, research has not proven theclinical utility of this family assessmenttool.'0,'247 However, studies have shownthat the genogram process captures morepsychosocial and biomedical informationthan traditional history taking.'4"15 Theresults of these research studies should notdiscourage family physicians from usinggenograms (only 10% to 20% of interventions used in medicine are supported byrandomized control trials'8). Futuregenogram research should focus on examining whether there is value in having agenogram as baseline information forevery patient's chart and what specificpatients, or particular patient problems,could benefit from genograms. 19ConclusionA genogram is a practical clinical tool thatfosters a family systems approach topatient care. Genograms give familyphysicians a quick, integrated picture ofpatients' biomedical and psychosocial histories. Genograms allow family physiciansto diagnose and manage difficult biopsychosocial clinical problems that often cannot be addressed using the traditional biomedical model. Genograms also assistTable 2. Benefits ofgenogramsSYSTEMATIC MEDICAL RECORD KEEPING* Easily read, graphic format* Identifies generational,biomedical, andpsychosocial patterns* Assesses connectionsbetween family context andillnessRAPPORT BUILDING* Nonthreatening way toobtain emotionally ladeninformation* Increases trust and patientcompliance* Demonstrates interest inpatient and significantothers* Reframes presentingproblem for patientsMEDICAL MANAGEMENT ANDPREVENTIVE MEDICINE* Highlights supports andobstacles to compliance* Identifies life events thatcould affect diagnosis andmanagement* Identifies illness patterns;facilitates patient educationAdaptedfrom McGoldrick.8Cnadian Family Physician VOL 40: Febmagy 1994285

Ftgur 3. Peter T.'s genogram The patient complain ofcest pain.Iuiwi sht hP eterT.'sI6UF A,--52U6E AM* Patient's relationshipwith his mother-in-law;* Patient's unresolvedgrief after the deatliof mother-in-law-, .50.WHACfIImCA(anniversary reaction);and* Patient's somatizationas a response to lossesand stressors.I. ., .".S!.T.!. ., . , . . .,.,-. 100.Case 2. This case study and genogram were drawn from St Michael's Hospital Family Practice Unit.T. was a 28-year-old marriedof Portuguese descent who hadbeen a patient of mine for about 2 years.My previous contact with him had beenminimal, consisting of an annual physicalexamination and a couple ofvisits regard-colleagues had left the company a month When I suggested that often the most difago to establish their own business, andficult things to discuss are the mostthey wanted him to join them. He had important ones to talk about, he becamebeen ambivalent about this, but finally tearful and began to express how muchdecided to remain with his company. he missed his wife's mother.Consequently he now had a more seniorShe had died the previous year after aing minor infections.position with his company and felt that yearlong battle with cancer. Peter statedWhen Peter came to see me at the clin- expectations of him were higher.that he was very close to her and in fact,ic, he was obviously agitated and disI established a working diagnosis of cos- "she was more like a mother to me." Astressed. He reported that he had been tochondritis, prescribed some coated we discussed this further, it became apparhaving some chest pain associated with aspirin, and suggested that Peter return to ent that Peter's grief regarding this lossdyspnea during the past 10 days, and that the clinic in 1 week. Three days after the was unresolved, as he had tried to remainhe had had to leave work and go home initial visit Peter phoned me in a very agi- strong for his wife and her family at theearly on a couple of occasions. As Peter tated state, saying that his symptoms had time of the death. In addition, Peter andtalked about this, he was extremely anxious not improved at all and that he in fact had his wife took on increased responsibilitiesand shaky. When I asked him what he to leave work early that day due to his for the extended family after this death,thought was going on, he initially said, "I chest pain. I tried to reassure him by demands that were difficult and anxietydon't know; that's why I came to see you." telling him that his chest x-ray examina- provoking for them.However as I persisted in trying to under- tion results were normal and that thereWhen I asked Peter if there were anystand his concerns and fears, he indicated were no indications of any serious physical similarities or parallels between that situathat he was worried that he might have health problems.tion and the recent changes at his worksome problem with his heart.When Peter came in for a follow-up place, he was able to identify that in bothWhile I did a physical examination, I appointment, he was again very anxious situations he had lost people about whominquired about the various risk factors and reported no significant change in his he had cared and on whom he hadassociated with heart disease, and discov- presenting problems. I explained to Peter depended. I also indicated to Peter that heered only one factor in his case (ie, his that often many factors contribute to was likely experiencing an anniversaryfather had been diagnosed with angina symptoms such as his, and that to under- reaction to his mother-in-law's death,about 4 years earlier). The examination stand these more clearly I needed to which was a normal and healthy part ofrevealed minimal tenderness along the left obtain more information.his grieving process.parasternal region with no other positiveI proceeded to construct his familyI explained to Peter that unresolvedfindings. I ordered a chest x-ray examina- genogram (Figure 3). As I asked Peter grief and other stressors in his life, comtion and did a cardiogram in the office questions about his own family, his bined with his anniversary reaction, were(which was normal).responses were quite matter-of-fact; howlikely the primary factors contributing toBecause I wondered whether Peter's ever, in contrast, he was cautious and his current symptoms. I suggested referralsymptoms were related to stress, I inquired apprehensive when talking about his to a social worker for counseling, andabout any recent changes or pressure in his wife's family. When I commented on this Peter accepted this saying, "Talking aboutlife. He told me of significant changes in observation, he indicated in a sad tone these things with you today has helped mehis work situation: some of his senior that it was difficult for him to talk about it. to see that they still bother me."Peterman286Canadian Family Physician VOL 40: Febmuary 1994

physicians to establish rapport withpatients and to have empathy with, andunderstanding of, patients' circumstances, especially when dealing withdifficult patients.URequests for reprints to: Mr I. Waters,Family Practice Unit, Groundfloor Eaton G-447,The Toronto Hospital, 200 Elizabeth St, Toronto,ON M5G2C4References1. Campbell T. Family interventions in physicalhealth. In: Sawa R, editor. Family health care.Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications,1992:213-26.2. Barrier D, Christie-SeelyJ. The presentinigproblems of families and family assessment.In: Christie-SeelyJ, editor. Working with thefamil in primagy care: a systems approach tohealth care and illness. New York: Praeger,1984:201-13.3. Mullins H, Christie-SeelyJ. Collecting andrecording family data - the genogram. In:Christie-SeelyJ, editor. Working with thefamilyin primagy care: a systems approach to health care andillness. New York: Praeger, 1984:179-91.4. Barrier D, Bybel M, Christie-SeelyJ,Whittaker Y. PRACTICE'- a familyassessment tool for family medicine. In:Christie-SeelyJ, editor. Taorkinlg wi/ith fatheianYin pnma9 care: a systems app)roach to health care anidillness. New York: Praeger, 1984:214-34.5. Doherty W, Colangelo N. The familyFIRO model: a modest proposal fororganiizing family treatment. 7 Alarital FarnTher 1984;10:19-29.6. 1.ike R, RogersJ, MIcGoldrick NI. Readinigand initerpreting geniograms: a systematicapproach. ] Farn Pract 1988;26(4):407- 12.7. Crouch NI, Davis T. Using the geniogram(family tree) clinically. In: Crouch NI,editor. Thefamilj in medical practice: afaniijsystems pnmer. New York: Springer-Verlag,1987:174-92.8. McGoldrick XI. Cenograms infamily assessment.New York: Norton Co, 1985:39-124.9. Crouch XI, Christie-SeelyJ. The (Roenlt)genogram of medicine; or using the familygenogram in patient care. Mled Encounter 1991;8(l):8-10.10. Rohrbaugh NI, RogersJ, lIcGoldrick NI.How do experts read family genograms? Fan7Systems Med 1992; 10(l): 79-89.11. Radomsky NA. Creatinig inews meaniitngthrough dialogue. A case story of chronic painatid scxuial abuse. Cani Faini Plasiriani 1992;38:2864-7.12. RogersJ, DuLrkiui NI. The semi-structuredgeniogrami interviews. I. Protocol. II.Evaluation. Famn Systems A fed 1984;2(2):176-87.13. Rogersj, Rohrbaugh NI. 'I'he SAGEI-PAGE,trial: clo family gclougiramiis make a difllireniee'7A4nm Board Faini hI-art 1991;4(5):319-26.14. RogersJ, Cohn P. Impaet of a screellingfatmily geuogram oll filrSt 11(LI)unters imprimary care. Famli hart 1987;4(4):291-301.1 5. RogersJ, Cohln P. The genogram'seontriblution to familc-cutredeare. .Aj7 AIed1 988;85(4):300-6.16. RogersJ, Hollowav R. Completion r-ate andrelilabilit of'thce self-administered geuiogram(SAG,E1). Famn Prart 1990;7(2): 149-51.17. Rogers J, Rohrhaugh NL. NMcGoldriek NI.Cau experts predict health risk from familygenr)grams? FamIMed 1992;24(3):20t-)15.18. Becker L. Isstucs in the adoptiou of a familyapproach by practisinig family phyvsicians. Ini:Sawsa R, editor. Family health rare. NewburvPark, Calif: Sage Ptublications, 1992:189-99.19. CampllrIT. Researclh relports: familyinterventions in faamily prac(tice. Fain SystemsMed 1992;10(2):227-9.* * -\;0f.E i500000ffffffffffffffFf000:ffff0LSo IL:fu;0 - 0:d ;m- 0REtt000000t0000000000:00:s0:00. ;02lDQ;::0t77t0:X;tE:-\XIFAA - CCP-i0:00:S Mi000000tm f

genograms Themainconcern expressed byfamily physicians is the length oftime it takes to completeagenogram. Somefamilyphysi-cians consider genogramsto be impracti-cal in abusyoffice practice because they increase the amountoftime spent onthe family history section ofthe office visit.'3 Familyphysicians whohave successfully integrated genograms .