Transcription

Alliance forChild Protection inHumanitarian ActionMEASURING SEPARATIONIN EMERGENCIESCommunity-based monitoringin rural Adwa, Tigray, EthiopiaCelina Jensen, Matthew MacFarlane,Beth L. Rubenstein, Terry Saw, Daniel Mekonnen,Katharine Williamson and Lindsay Stark

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis pilot in Ethiopia is part of the MeasuringSeparation in Emergencies (MSiE) project, fundedby the USAID Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance(OFDA). The MSiE project is implemented by Savethe Children in partnership with Columbia University,and steered by an interagency Advisory Panel.The work reported here was coordinated andmanaged by Save the Children. Columbia Universityis the intellectual and methodological lead on thecommunity-based monitoring approach. The pilotwas conducted in collaboration with the InternationalOrganization for Migration (IOM) in Ethiopia.This pilot would not have been possible without thesupport of the government of Ethiopia, particularlythe Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs, or thesupport of and collaboration with UNICEF Ethiopiaand the national Child Protection Sub-Cluster. Inparticular, we would like to thank Mini Bhaskar andEphrem Belay (UNICEF), Elizabeth Cosser (ChildProtection Working Group) and Hiruy BahretibebFeleke (Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs).Special thanks go to the male and female communityfocal points for their dedicated work. They gavea substantial amount of their time and effort to k Hadush, Tekla Welagebriel, ryam, Gebrezgher Neway, GebrehansMesfin, Kide Hagos, Mebrahtu Gebresilassie,Gebremedhin Gebrelibanos, Tirhas Gebremedhin,Alamnesh Negash, Yihanisu Gebru, hid Welegerima, Kiros Yared, ZemichaelKide, Freweine Tesfay, Haylay Asgela, , Tsehanesh Tsegay, Zekaryas Hagos, andKidanamaryam Berhe.The hard work of Anna Skeels, MSiE ProjectManager, and Craig Spencer, Columbia Universitymethodologist, was instrumental in setting up andsupporting the pilot. Terry Saw, a Masters studentat Columbia University, was instrumental in effectivedata collection and data analysis for this pilot.Finally, we appreciate the strategic support andguidance of the project’s Advisory Panel membersand their input into this pilot, namely: MonikaSandvik-Nylund, Janis Ridsdel (UNHCR), MathildeBienvenu, Claudia Cappa and Ibrahim Sesay(UNICEF), Florence Martin (Better Care Network),Mark Canavera (CPC Learning Network), JessicaLenz (InterAction), Nicole Richardson (Save theChildren), Monica Noriega, Amina Saoudi (IOM),Anne Laure Baulieu, Annalisa Brusati and YvonneAgengo (International Rescue Committee). Thanksalso go to Hani Mansourian (Alliance for ChildProtection in Humanitarian Action) and Layal Sarrouh(Child Protection Area of Responsibility).Published on behalf of the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action bySave the Children1 St John’s LaneLondon EC1M 4ARUK 44 (0)20 7012 6400savethechildren.org.ukFirst published 2018 The Save the Children Fund 2018The Save the Children Fund is a charity registered in England and Wales (213890) andScotland (SC039570). Registered Company No. 178159This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee or priorpermission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any other circumstances,prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable.Cover photo: Matt MacFarlaneTypeset by Grasshopper Design CompanyCommunity-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESCONTENTSExecutive Pilot context 11Design and methods 12Findings 16Discussion 22Learning and implications SCPWGChild Protection Working GroupDRCDemocratic Republic of CongoIOMInternational Organization for MigrationMSiEMeasuring Separation in EmergenciesUASCUnaccompanied and separated childrenCommunity-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia1

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESEXECUTIVE SUMMARYFamilies are the basic protective unit for children in society and, in almost allcases, provide the best environment for meeting a child’s developmental needs.The separation of children from their families is one of the most significantimpacts that humanitarian crises have on individuals’ lives worldwide. Identifyingsafe and supportive interim care for children, and undertaking family tracingand reunification activities to reunite them with their family following onset ofan emergency, are two of the most significant protective and psychologicalinterventions that humanitarian actors can carry out during an emergency.Background to Measuring Separation in EmergenciesThe Measuring Separation in Emergencies (MSiE) project is an interagencyinitiative under the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, fundedby the USAID Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) and coordinatedby Save the Children in partnership with Columbia University. The overall aimof the MSiE project is to strengthen emergency response programmes forunaccompanied and separated children (UASC) through the development ofpractical, field-tested methods to enhance the assessment of the scale andnature of separation in emergencies.To address this gap in data on UASC, in 2014 the Assessment and MeasurementTask Force of the Global Child Protection Working Group (CPWG) 1 launched aninteragency initiative to develop a project to generate rigorous statistics aboutUASC across a range of emergency settings. The project had several componentseach of which had specific methods to measure separation. Three componentswere initially explored with a fourth component, the residential care approach,being included following the initial pilots in 2014:1. Projection approach aims to use existing population data from a givenlocation, combined with empirical data from comparable emergencies, togenerate models of UASC risk profiles characteristic of certain emergencytypes and phases, and to test or validate those projections against actual datain existing or evolving emergencies.2. Population-based estimation approach aims to provide a populationbased estimation of the prevalence, number and basic characteristics of UASCin a defined area, affected by the same emergency, at any given point in time.3. Community-based monitoring approach incorporates a community-basedmonitoring system capable of continuous, ongoing measurement of trends inthe frequency and basic characteristics of UASC in defined areas over time.1Later renamed the Assessment, Measurement and Evidence Working Group upon transition from the CPWG tothe Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action in 2016.2Community-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIES4. Residential care approach is designed to capture the scale of movementsof children into residential care facilities as a result of an emergency.This report focuses primarily on the community-based monitoring approach,developed by Columbia University, and the field testing of this approach inthe Tigray region of Ethiopia from June to December 2016. The InternationalOrganization for Migration (IOM) office in Ethiopia hosted the pilot research withthe support of Save the Children.Ethiopia contextThe monitoring system was established in 10 villages in the Adwa district of theTigray region. The Adwa district is located adjacent to the communities mostseverely affected by drought, and therefore local partners expected significantmovement of children throughout this area. The government also contributed toidentifying locations for the monitoring system based on expected numbers ofchild separation cases moving through the region as well as accessibility and cellphone network reliability. Through engagement with the government, five kebeles(the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia, generally composed of approximately2,000 households) were identified and deemed as appropriate for the study.Focal point selection processCommunity-based monitoring relies on selected community members to act asfocal points to provide regular reports about the situation where they live. Therationale is that community members will be privy to insider knowledge aboutthe people who live close to them, and with proper organisation, training andincentives this knowledge can be routinely gathered and centralised to get apicture of a given issue.During visits to the villages with the kebele chairperson, residents were given anoverview of the pilot and asked to provide feedback as well as give their consentto participate in the research. Residents in all 10 villages gave their consent tothe process. Each village then held an election to choose three focal points pervillage. Two focal points came from the existing village leadership structure andone came from outside that structure. It was required that at least one focal pointfrom each village be a woman.The next step was for the research team to meet with the focal points to identifyand agree upon a clearly defined reporting area of 100 to 200 households withinwhich the focal points would be responsible for reporting cases of separation. Insome villages, this reporting area covered a small, relatively densely populatedgeographic area, while in other villages the reporting area encompassed largefields and farms. By including both types of communities, the project was betterable to represent the diversity of conditions in the region.Community-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia3

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESReporting protocolWhen a focal point learned of a case of separation in his or her reporting zone,she or he was asked to send a text message containing a numeric code to theproject coordinator’s central phone. Whenever possible, this six-component codeprovided the following information about each child: age (exact or approximate) sex whether the child arrived in the community, departed from the community,or was remaining in the same community whether the child was separated or unaccompanied reason(s) for the separation current caregiver(s).Data retrieval and verificationAll of the text messages were sent to a central smartphone connected toFrontlineSMS, a free, open-source software that enables automatic transmissionof coded text messages to a special web-based inbox. This set-up allowedproject and research staff to remotely retrieve and monitor reports from villages.Every time a case report was received via the FrontlineSMS system, the projectcoordinator phoned the focal point who had sent the case information to verifytheir report and, if necessary, request that a corrected code be sent.FindingsThe findings from this pilot suggest that a community-based monitoring approachusing mobile phones has the potential to generate important informationfor programmes responding to child separation in slow-onset humanitarianemergencies. Over the course of the six-month study period, 48 individual casesof unaccompanied and separated children were reported and verified. Of these48 cases, 21 were children who had arrived in the community, nine had becomeseparated without changing communities, and 18 were children who had left theircommunity; 19 children (40%) were classified by focal points as unaccompanied.Distribution of reporting varied across months, ranging from 23 cases in July toone case in October. Most departures occurred in July and September and mostarrivals occurred in July, August and December. There was also wide variation inthe number of cases per village, with one village reporting no cases throughoutthe study period and another village reporting more than 10.4Community-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESLessons learned and conclusionThe lessons learned from piloting the community-based monitoring approach inEthiopia include:1. Clarify definitions of an unaccompanied child and a separated child, bothto align with international definitions and to understand and align with localdefinitions and how these intersect with vulnerability. Nearly 40% of thereported separations were unaccompanied children. Despite conductingtraining that included a specific module on definitions of both unaccompaniedand separated children, it is possible that focal points did not fully grasp theconcept of separation, and did not include children who were separated butunder the care of a relative.2. Take steps to ensure that focal points are motivated to maintain engagementpotentially by taking a more structured approach to case identification. Overa longer time period (for instance 6–9 months) a small stipend may helpmaintain focal point motivation. In addition, a more structured approach tocase finding, such as visiting each home on a regular basis or selecting focalpoints that already visit each household, could improve overall accuracy ofthe monitoring system. Motivation and case finding appear to overlap: findingcases contributes to improved motivation, which indicates that it may bepossible to improve both accuracy and motivation over time.3. Consider the reliability of network service on the technology used and plan foralternative solutions.4. Ensure that focal points are elected at community level by community members.The pilot found that the most significant predictor of consistent reporting inEthiopia was whether or not a focal point was elected by their community.5. Link the monitoring approach to active case follow-up and to family tracingand reunification efforts.This study describes a second pilot survey that aimed to determine the efficacy andfeasibility of a community-based monitoring system in a slow-onset emergencycontext. The findings from the survey have important programming implicationsfor emergency responses in the Ethiopian setting and beyond.Given the increasing interest among practitioners to have simple, low-costapproaches to better identify unaccompanied and separated children inemergencies, the findings from this study suggest that the monitoring approachmay provide useful information, while also pointing to the need to adapt andcontextualise the system with different levels of support and focal point selection.The potential for such an ongoing source of data to complement family tracingand reunification activities presents new opportunities for programme planningand emergency responses to support vulnerable children and families.Community-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia5

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESBACKGROUNDFamilies are the basic protective unit for children in society and, in almost allcases, provide the best environment for meeting a child’s developmental needs.The separation of children from their families is one of the most dramatic impactsthat humanitarian crises have on individuals’ lives worldwide. Separation mayoccur accidentally as a consequence of the emergency, for instance duringsudden displacement, or deliberately when adults are forced to make difficultdecisions about what they feel is in the best interests of their family. Separationmay also occur by force, such as in abduction, trafficking or forced recruitment. Inaddition, the actions of humanitarian organisations themselves can unintentionallyresult in separation, for example, during medical evacuations or by targetingunaccompanied and separated children for humanitarian assistance. Secondaryseparation, for example from an interim caregiver, may occur when the capacityof caregivers to cope is eroded over time.The family is central to protecting the child from threats and risks and inproviding an environment to support the healthy development of the child. Anunaccompanied 2 or separated 3 child is therefore vulnerable and at greater risk ofviolence, abuse, exploitation or neglect. Identifying safe and supportive interimcare for children, and undertaking family tracing and reunification activities toreunite them with their family following onset of an emergency, are two of themost significant protective and psychological interventions that humanitarianactors can carry out during an emergency. Yet despite investments in serviceprovision, there are no known tools or approaches to determine a representativeestimate of the number of unaccompanied and separated children (UASC) ina given humanitarian emergency. Without a sense of how many children areseparated, practitioners must rely on a mix of generalised assumptions andselective information to design and target their activities. In addition, advocatesfor separated children are limited in their ability to secure funding, as they cannotprovide donors with accurate information on the scale of the problem.The rule of thumb used by most child protection actors is that separated childrencomprise approximately 3–5% of the displaced population in an emergencycontext. Unfortunately, this assumption has never been validated and, moreover,it discounts the complex nature of not only different emergency situations, butalso different cultural contexts in which the profile of separation may diverge2Unaccompanied children (also referred to as unaccompanied minors) are children, as per the definition in theUnited Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), who have been separated from both parents andother relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.3Separated children are children, as per the definition in the UNCRC, who have been separated from both parents,or from their previous legal or customary primary caregiver, but not necessarily from other relatives. These may,therefore, include children accompanied by other adult family members.6Community-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESsignificantly. Recognising this diversity, the Child Protection Rapid Assessment(CPRA) Toolkit was designed to gather context-specific information on UASCsix to eight weeks following an emergency event. However, the CPRA producesqualitative data that is not representative of an entire affected area.Currently, there are no standard assessment measures to gather data aboutongoing trends in the scale and characteristics of the separation of children overtime, which creates challenges in the implementation of response mechanisms.Further, without a dynamic understanding of the movement of separated children,implementing organisations are unable to target and adapt their programmeseffectively for maximum impact. To address the gap in capturing changes inseparation over time, in 2014 the Assessment and Measurement Task Force ofthe Global Child Protection Working Group (CPWG) 4 launched an interagencyinitiative to develop a core set of approaches to generate rigorous statistics aboutUASC across a range of emergency settings. Through a close partnership with anAdvisory Panel composed of practitioners, policymakers and donors, researchersfrom Columbia University in New York came together to design an approachfor measuring trends in emergency-related separation in protracted emergencysettings in order to better inform humanitarian responders and advocates.Following in-depth discussions, the Advisory Panel recommended a communitybased monitoring approach as a cost-effective way to benefit from and engagewith local awareness of children’s movement over a prolonged period of time.The aim was to measure trends in the frequency of separation and the basiccharacteristics of UASC in defined areas. Community-based monitoring relies ona network of trained community members who relay specific observations abouttheir surroundings to a central body on a regular basis.Monitoring systems can be created to monitor issues that need urgent attentionor can be used to monitor long-term trends. They tend to provide more‘real-time’ information, which is important in situations of rapid change in orderto respond quickly. Continuous data collection is helpful when the ability to trenddata or to detect changes in occurrence or distribution is desired. The approachhas been used to gather information about topics ranging from infectiousdiseases to maternal health and nutrition in hard-to-reach areas.5 In addition,borrowing from the success of community-based monitoring systems in otherresource-poor settings, it was proposed that data be collected through the use ofmobile phones.6 Compared with paper-based reporting, phone-based reportingincreases the speed and efficiency of community-based monitoring systems.74See previous note on the transition.Boothby N, Stark L (2011); Bowden S, Braker K, Checchi F, Wong S (2012); Cox J, Dy Soley L, Bunkea T et al.(2014); Curry D, Bisrat F, Coates E, Altman P (2013); Rosales A, Galindo J, Flores A (2010)56Kindade S, Verclas, K (2008); Van der Windt P, Humphreys M (2014)7Lucas H, Greeley M, Roelen K (2013)Community-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia7

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESThe first iteration of the community-based monitoring system to measureunaccompanied and separated children was tested in the Democratic Republicof Congo (DRC) in 2014.8 This 11-week pilot took place in 10 village sites inthe conflict-affected region of North Kivu in eastern DRC. While the pilot led tovaluable learning, a number of key questions and areas for improvement wereidentified, including a more rigorous comparison of focal point performance bygender and community position and an evaluation of medium-term sustainabilityof monitoring beyond 11 weeks. Importantly, the Advisory Panel and the researchteam also concluded that differences between chronic emergency situations,such as conflict-affected eastern DRC, and slow-onset emergencies, such as aslow-onset natural disaster emergency, necessitated a second pilot of the survey.This report presents the findings from the second pilot of the community-basedmonitoring system, carried out over a six-month period in 2016 during the droughtin the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia.88Rubenstein BL, Spencer C, Mansourian H, Noble E, Munganga GB, Stark L (2015)Community-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESINTRODUCTIONThe Measuring Separation in Emergencies (MSiE) Project is an interagencyinitiative under the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action funded bythe USAID Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) and coordinated by Savethe Children in partnership with Columbia University. The project is steered by aninteragency Advisory Panel, including members of the Inter-agency Working Groupon Unaccompanied and Separated Children and the Assessment, Measurementand Evidence Working Group of the Alliance for Child Protection in HumanitarianAction. The overall aim of the MSiE project is to strengthen emergency responseprogrammes for unaccompanied and separated children (UASC) through thedevelopment of practical, field-tested approaches to enhance the assessment ofthe scale and nature of separation in emergencies.The humanitarian community has significant experience and expertise in workingwith unaccompanied and separated children (UASC). However, the lack of robustdata available on UASC in emergencies makes it extremely difficult to: generate adequate and timely funding design and implement appropriate programmes strengthen relevant child protection systems, and influence national andinternational policies and laws relating to separation.Save the Children, Columbia University, and members of the interagency AdvisoryPanel have worked together to pilot tools that will more effectively measureseparation in emergencies. The aim is to strengthen emergency responseprogramming for UASC through the development of practical, operationallysound approaches that can be used in most emergency contexts to generaterobust measurement and assessment of the scale and nature of separation. Atthe project outset, a set of four key questions (for all stages of an emergency)provided a broad framework for discussion on the required focus of these newapproaches to measurement:1. How many UASC are there?2. Where are UASC now, where have they come from, where are they going?3. What are the causes of separation, which children are most vulnerable to themand why?4. What are the main needs of UASC? What protection risks are they facing?Informed by desk research and consultation with a range of stakeholders,technical child protection input from the Advisory Panel members, and guidanceon appropriate methodologies from Columbia University, consensus was gainedat a ‘Methodology Kick-Off Workshop’ on the methodological approaches to beexplored. Participants agreed that the priority would be to focus on the estimationor enumeration of UASC, but that more qualitative questions (for example, theCommunity-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia9

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIEScauses of separation and the needs of UASC) would also be addressed whereand to the extent feasible. Three approaches were initially explored with a fourthapproach, the residential care approach, being included following the initial pilotsin 2014:1. Projection approach aims to use existing population data from a givenlocation, combined with empirical data from comparable emergencies, togenerate models of UASC risk profiles characteristic of certain emergencytypes and phases and to test or validate those projections against actual datain existing or evolving emergencies.2. Population-based estimation approach aims to provide a populationbased estimation of the prevalence, number and basic characteristics of UASCin a defined area, affected by the same emergency, at any given point in time.3. Community-based monitoring approach incorporates a community-basedmonitoring system capable of continuous, ongoing measurement of trends inthe frequency and basic characteristics of UASC in defined areas over time.4. Residential care approach is designed to capture the scale of movementsof children into residential care settings as a result of an emergency.The MSiE project has been implemented in two phases. In Phase 1, the populationbased estimation and the community-based monitoring approaches were bothpiloted in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2014. Following positive results,lessons learned and recommendations from reports published in 2014, Phase 2was planned to include a second field test of the community-based monitoringapproach in northern Ethiopia in 2016 during a drought as well as of the populationbased estimation approach in Haiti in a rapid-onset emergency situation followingHurricane Matthew in 2017. The emergency in Haiti also presented an opportunityto pilot a new tool focusing on the movement of children post-emergency into andout of residential care settings.This report focuses primarily on the community-based monitoring approach,developed by Columbia University, and the field-testing of this approach inthe Tigray region of Ethiopia from June to December 2016. The InternationalOrganization for Migration (IOM) office in Ethiopia hosted the pilot research withthe support of Save the Children.10Community-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia

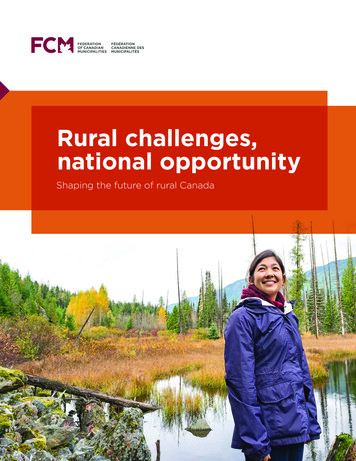

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESPILOT CONTEXTThe community-based monitoring system was set up in the Tigray region ofnorthern Ethiopia in June 2016 because of the impending famine caused by a severedrought throughout the region. It was predicted that the impact of the drought onlivelihoods and consequent increased rates of malnutrition would lead to familyseparation. This context therefore offered an opportunity to monitor separationover time in the context of a slow-onset food insecurity crisis. The system wasdeveloped in partnership with Save the Children and IOM in close collaborationwith the government of Ethiopia and the national Child Protection Sub-Cluster.The primary goal was to measure trends in the scale and characteristics of UASC,while the secondary goal was to generate learning for refining the data collectionapproaches and tools needed to conduct similar research in other settings inthe future.The monitoring system was established in 10 villages in the Adwa district of the Tigrayregion. The Adwa district is adjacent to the communities most severely affected bythe drought, and therefore local partners expected significant movement of childrenthroughout this area. The government also contributed to identifying locations for themonitoring system based on expected numbers of child separation cases movingthrough the region as well as on accessibility and cell phone network reliability.Through engagement with the government, five kebeles (the smallest administrativeunit in Ethiopia, generally composed of approximately 2,000 households), wereidentified and deemed to be appropriate for the study.Figure 1: Maps of Ethiopia and TigrayAdwaEasternTigrayWestern TigrayCentralTigrayEritreaSudanRed SeaTigrayBenishangulGumazAfarAmharaDjiboutiGulf of AdenAddis AbabaHarariOromiaEthiopiaGambelaSouthSudanSouthern Nations,Nationalitiesand PeoplesSomaliSomaliaUgandaSouthernTigrayDire DawaKenyaArabianSeaCommunity-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia11

MEASURING SEPARATION IN EMERGENCIESDESIGN AND METHODSThe research team included methodologists from Columbia University and theMSiE project manager from Save the Children UK. The team partnered with theIOM office in Tigray, which was used as a base to conduct the study. A dedicatedproject coordinator, local to Tigray, was hired by IOM to serve as the main fieldagent and point of contact for the community focal points. Services for urgentactions and referrals were provided in partnership with existing local responsestructures, particularly the Mi

Community-based monitoring in rural Adwa, Tigray, Ethiopia 3 4. Residential care approach is designed to capture the scale of movements of children into residential care facilities as a result of an emergency. This report focuses primarily on the community-based monitoring approach,