Transcription

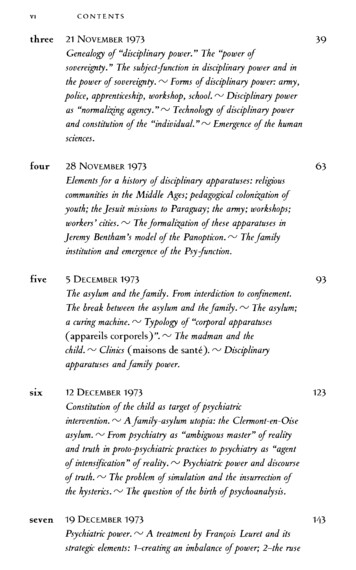

CONTENTSVIthree21 NOVEMBER 197339Genealogy of "disciplinary power." The "power ofsovereignty.yy The subject function in disciplinary power and inthe power of sovereignty. Forms of disciplinary power: army,police, apprenticeship, workshop, school. Disciplinary poweras "normalizing agency." Technology of disciplinary powerand constitution of the "individual." Emergence of the humansciences.four28NOVEMBER197363Elements for a history of disciplinary apparatuses: religiouscommunities in the Middle Ages; pedagogical colonisation ofyouth; the Jesuit missions to Paraguay; the army; workshops;workers' cities. The formali ation of these apparatuses inJeremy Bentham's model of the Panopticon. The familyinstitution and emergence of the Psy function.five5DECEMBER197393The asylum and the family. From interdiction to confinement.The break between the asylum and the family. The asylum;a curing machine. nu Typology of "corporal apparatuses(appareils corporels) ". The madman and thechild. r f Clinics (maisons de sante). Disciplinaryapparatuses and family power.six12 DECEMBER 1973123Constitution of the child as target of psychiatricintervention. A family-asylum utopia: the Clermont-en-Oiseasylum. From psychiatry as "ambiguous master" of realityand truth in proto-psychiatric practices to psychiatry as "agentof intensification " of reality. Psychiatric power and discourseof truth. The problem of simulation and the insurrection ofthe hysterics. The question of the birth of psychoanalysis.seven19DECEMBER1973Psychiatric power. A treatment by Francois Leuret and itsstrategic elements: 1-creating an imbalance of power; 2-the ruse17l3

Contentsviiof language; 3-the management of needs; 4-the statement oftruth. The pleasure of the illness. The asylum tric power and the practice of "direction". The gameof "reality " in the asylum. The asylum, a medicallydemarcated space and the question of its medical oradministrative direction. The tokens of psychiatric knowledge:(a) the technique of questioning; (b) the interplay ofmedication and punishment; (c) the clinicalpresentation. Asylum "microphy sics of power." Emergenceof the Psy function and of neuropathology. The triple destinyof psychiatric power.nine16 JANUARY 1974201The modes of generalization of psychiatric power and thepsychiatrixation of childhood. 1. The theoretical specificationof idiocy. The criterion of development. Emergence of apsy chop athology of idiocy and mental retardation. EdouardSeguin: instinct and abnormality. 2. The institutionalannexation of idiocy by psychiatric power. The "moraltreatment" of idiots: Seguin. The process of confinement andthe stigmati\ation of the dangerousness of idiots. Recourse tothe notion of degeneration.ten23 JANUARY 1974233Psychiatric power and the question of truth: questioning andconfession; magnetism and hypnosis; drugs. Elements for ahistory of truth: 1. The truth-event and its forms: judicial,alchemical and medical practices. Transition to a technologyof demonstrative truth. Its elements: (a) procedures of inquiry;(b) institution of a subject of knowledge; (c) ruling out thecrisis in medicine and psychiatry and its supports: thedisciplinary space of the asylum, recourse to pathologicalanatomy; relationships between madness andcrime. Psychiatric power and hysterical resistance.

vnielevenCONTENTS30 JANUARY 197 7 IThe problem of diagnosis in medicine and psychiatry. 265Theplace of the body in psychiatric nosology: the model of generalparalysis. The fate of the notion of crisis in medicine andpsychiatry. The test of reality in psychiatry and its forms:1. Psychiatric questioning (l'interrogatoire) and confession.The ritual of clinical presentation. Note on "pathologicalheredity" and degeneration. 2. Drugs. Moreau de Tours andhashish. Madness and dreams. 3. Magnetism and hypnosis.The discovery of the "neurological body."twelve6 FEBRUARY 1974297The emergence of the neurological body: Broca and Duchennede Boulogne. Illnesses of differential diagnosis and illnessesof absolute diagnosis. The model of "generalparalysis" andthe neuroses. The battle of hysteria: 1. The organisation of a"symptomatological scenario." 2. The maneuver of the"functional mannequin " and hypnosis. The question ofsimulation. 3. Neurosis and trauma. The irruption of thesexual body.Course Summary335Course Context3zl9Index of N a m e s369Index of N o t i o n s376Index of Places383

FOREWORDMICHEL FOUCAULT TAUGHT AT the College de France From January1971 until his death in J u n e 1984 ( w i t h the exception of 1977 when hetook a sabbatical year). The title of his chair was "The History olSystems of Thought."On the proposal of Jules Vuillemin, the chair was created on 30November 1969 by the general assembly of the professors of the Collegede France and replaced that of "The History of Philosophical Thought"held by Jean Hyppolite until his death. The same assembly electedMichel Foucault to the new chair on 12 April 1970.' He was 43 years old.Michel Foucault's inaugural lecture was delivered on 2 December1970. 2 Teaching at the College de France is governed by particular rules.Professors must provide 26 hours of teaching a year ( w i t h the possibility of a maximum of half this total being given in the form of seminars ).Each year they must present their original research and this obligesthem to change the content of their teaching for each course. Coursesand seminars are completely open; no enrolment or qualification isrequired and the professors do not award any qualifications/ 1 In the terminology of the College de France, the prolessors do not have studentsbut only auditors.Michel Foucault's courses were held every Wednesday from January toMarch. The huge audience made up ol students, teachers, researchers andthe curious, including many who came Irom outside France, required twoamphitheaters of the College de France. Foucault olten complained aboutthe distance between himsell and his "public" and ol how lew exchangesthe course made possible. 5 He would have liked a seminar in which realcollective work could take place and made a number of attempts to bring

XFOREWORDthis about. In the final years he devoted a long period to answering hisauditors' questions at the end of each course.This is how Gerard Petitjean, a journalist from Le Nouvel Observateur,described the atmosphere at Foucault's lectures in 1975:When Foucault enters the amphitheater, brisk and dynamic likesomeone who plunges into the water, he steps over bodies to reachhis chair, pushes away the cassette recorders so he can put downhis papers, removes his jacket, lights a lamp and sets off at fullspeed. His voice is strong and effective, amplified by loudspeakersthat are the only concession to modernism in a hall that is barelylit by light spread from stucco bowls. The hall has three hundredplaces and there are five hundred people packed together, fillingthe smallest free space . . . There is no oratorical effect. It is clearand terribly effective. There is absolutely no concession to improvisation. Foucault has twelve hours each year to explain in a p u b lic course the direction taken by his research in the year justended. So everything is concentrated and he fills the margins likecorrespondents who have too much to say for the space available tothem. At 19.15 Foucault stops. The students rush towards hisdesk; not to speak to him, but to stop their cassette recorders.There are no questions. In the pushing and shoving Foucault isalone. Foucault remarks: "It should be possible to discuss what Ihave put forward. Sometimes, when it has not been a good lecture,it would need very little, just one question, to put everythingstraight. However, this question never comes. The group effect inFrance makes any genuine discussion impossible. And as there isno feedback, the course is theatricalized. My relationship with thepeople there is like that of an actor or an acrobat. And when I havefinished speaking, a sensation of total solitude . . ." 6Foucault approached his teaching as a researcher: explorations for afuture book as well as the opening up of fields of problematization wereformulated as an invitation to possible future researchers. This is why thecourses at the College de France do not duplicate the published books.They are not sketches for the books even though both books and courses

Forewordxishare certain themes. They have their own status. They arise from a specificdiscursive regime within the set of Foucault's "philosophical activities." Inparticular they set out the programme for a genealogy of knowledge/powerrelations, which are the terms in which he thinks of his work from thebeginning of the 1970s, as opposed to the programme of an archeology ofdiscursive formations that previously orientated his work.7The courses also performed a role in contemporary reality. Those whofollowed his courses were not only held in thrall by the narrative thatunfolded week by week and seduced by the rigorous exposition, they alsofound a perspective on contemporary reality. Michel Foucault's art consisted in using history to cut diagonally through contemporary reality. Hecould speak of Nietzsche or Aristotle, of expert psychiatric opinion or theChristian pastoral, but those who attended his lectures always took fromwhat he said a perspective on the present and contemporary events.Foucault's specific strength in his courses was the subtle interplaybetween learned erudition, personal commitment, and work on the event.*With their development and refinement m the 1970s, Foucault's deskwas quickly invaded by cassette recorders. The courses—and someseminars—have thus been preserved.This edition is based on the words delivered in public by Foucault. Itgives a transcription of these words that is as literal as possible. 8 Wewould have liked to present it as such. However, the transition from anoral to a written presentation calls for editorial intervention: At the veryleast it requires the introduction of punctuation and division into paragraphs. O u r principle has been always to remain as close as possible tothe course actually delivered.Summaries and repetitions have been removed whenever it seemed tobe absolutely necessary. Interrupted sentences have been restored andfaulty constructions corrected. Suspension points indicate that therecording is inaudible. When a sentence is obscure there is a conjecturalintegration or an addition between square brackets. Anasteriskdirecting the reader to the bottom of the page indicates a significantdivergence between the notes used by Foucault and the words actually

xiiFOREWORDuttered. Quotations have been checked and references to the texts usedare indicated. The critical apparatus is limited to the elucidation ofobscure points, the explanation of some allusions and the clarification ofcritical points. To make the lectures easier to read, each lecture is preceded by a brief summary that indicates its principal articulations. 9The text of the course is followed by the summary published by theAnnuaire du College de France. Foucault usually wrote these in June, sometime after the end of the course. It was an opportunity for him to pickout retrospectively the intention and objectives ol the course. It constitutes the best introduction to the course.Each volume ends with a "context" for which the course editors areresponsible. It seeks to provide the reader with elements of the biographical, ideological, and political context, situating the course withinthe published work and providing indications concerning its placewithin the corpus used in order to facilitate understanding and to avoidmisinterpretations that might arise from a neglect of the circumstancesin which each course was developed and delivered.Psychiatric Power, the course delivered in 1973 and 1974, is edited byJacques Lagrange.*A new aspect of Michel Foucault's "oeuvre" is published with thisedition of the College de France courses.Strictly speaking it is not a matter of unpublished work, since thisedition reproduces words uttered publicly by Foucault, excluding theoften highly developed written material he used to support his lectures.Daniel Defert possesses Michel Foucault's notes and he is to be warmlythanked for allowing the editors to consult them.This edition of the College de France courses was authorized byMichel Foucault's heirs who wanted to be able to satisfy the strongdemand for their publication, in France as elsewhere, and to do thisunder indisputably responsible conditions. The editors have tried to beequal to the degree ol conlidence placed in them.F R A N C O I S EWALD A N D A L E S S A N D R O F O N T A N A

Forewordxiii1. Michel Foucault concluded a short document drawn up in support of his candidacy withthese words: "We should undertake the history ol systems of thought." "Titres et travaux,"in Dils et Ecrits, 195/l-19S8, four volumes, ed. Daniel Defert and Francois Ewald (Paris:Gallimard, 1994) vol. 1, p. 846; English translation, "Candidacy Presentation: College deFrance," in The Essential Works of Michel Foucault, 1954-1984, vol. 1: Ethics: Subjectivity andTruth, ed. Paul Rabinow, trans. Robert Hurley and others (New York: The New Press,1997) p. 9.2. It was published by Gallimard in May 1971 with the title VOrdre du discours (Paris).English translation: "The Order of Discourse," trans. Rupert Swyer, appendix toM. Foucault, The Archeology of Knowledge (New York: Pantheon, 1972).3. This was Foucault's practice until the start of the 1980s.4. Within the framework of the College de France.5. In 1976, in the vain hope of reducing the size of the audience, Michel Foucault changed thetime of his course from 17/i5 to 9 . 0 0 . See the beginning of the lirst lecture (7 January1976) ol "1/ Jaut defendre la societe". Cours au College de France, 1976 (Pans:Gallimard/Seuil, 1997); English translation, "Society Must be Defended". Lectures at theCollege de France 1975-1976, trans. David Macey (New York: Picador, 2 0 0 3 ) .6. Gerard Petitjean, "Les Grands Pretres de I'universite Iranc.aise," Lc Nouvel Observateur,1 April 19757. See especially, "Nietzsche, la genealogie, I'histoire," in Dils et Ecrils, vol. 2, p. 137. Englishtranslation, "Nietzsche, Genealogy, History," trans. Donald F. Brouchard and SherrySimon in, The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984, vol. 2: Aesthetics, Method, andEpistemology, ed. James Faubion, trans. Robert Hurley and others (New York: The NewPress, 1998), pp. 369 92.8. We have made use ol the recordings made by Gilbert Burlet and Jacques Lagrange inparticular. These are deposited in the College de France and the Institut Memoires deI'Edition Contemporaine.9. At the end of the book, the criteria and solutions adopted by the editors ol this year'scourse are set out in the "Course context."

INTRODUCTIONArnold I. DavidsonMICHEL FOUCAULT'S CENTRAL CONTRIBUTION to political philosophywas his progressive development and refinement of a new conception ofpower, one that put into question the two reigning conceptions ofpower, the juridical conception found in classical liberal theories and theMarxist conception organized around the notions of State apparatus,dominant class, mechanisms of conservation, and juridical superstructure. If the first volume of his history of sexuality, La Volonte de savoir( 1 9 7 6 ) , is a culminating point of this dimension of Foucault's work, hiscourses throughout the 1970s return again and again to the problem ofhow to analyze power, continually adding historical and philosophicaldetails that help us to see the full import and implications of his analytics of power. At the beginning of the chapter "Methode" in La Volontede savoir Foucault warns his readers against several misunderstandingsthat may be occasioned by the use of the word "power," misunderstandings concerning the identity, the form, and the unity of power.Power should not be identified, according to Foucault, with the set ofinstitutions and apparatuses in the State; it does not have the form ofrules or law; finally, it does not have the global unity of a general systemof domination whose effects would pass through the entire social body.Neither state institutions, nor law, nor general effects of dominationconstitute the basic elements of an adequate analysis of how powerworks in modern societies. 1 Without having yet developed all of the toolsof his own analysis, Psychiatric Power already exhibits Foucault's awareness of the shortcomings of available conceptions of power, and nowheremore clearly than in his own critique of notions implicit or explicit in

Introductionxvhis Histoire de la folk. Foucault's dissatisfaction with his previous analysis of asylum power centers around two basic features ol the analysisin Histoire de lafolie: first, the privileged role he gave to the "perceptionof madness" instead of starting, as he does in Psychiatric Power, from anapparatus of power itself; second, the use of notions that now seem tohim to be "rusty locks with which we cannot get very far" and thattherefore compromise his analysis of power as it is articulated in Histoirede lafolie.2As regards this second point, Foucault's critique of his own use of thenotions of violence, of institution, and of the family can be seen in retrospect to be an important part of his development of that alternativemodel of power that will be at the center of Surveiller et punir and LaVolonte de savoir. In effect, Foucault's criticisms here take aim precisely atassumptions concerning the identity, the form, and the unity of power.Rather than thinking of power as the exercise of unbridled violence, oneshould think of it as the "physical exercise of an unbalanced force" (inthe sense of an unequal, non symmetrical force), b u t a force that actswithin "a rational, calculated, and controlled game of the exercise ofpower.' 0 Instead of conceptualizing psychiatric power in terms of institutions, with their regularities and rules, one has to understand psychiatric practice in terms of "imbalances of power" with the tactical uses of"networks, currents, relays, points of support, differences of potential"that characterize a form of power/ 1 Finally, in order to understand thefunctioning of asylum power, one cannot invoke the paradigm of thefamily, as if psychiatric power "does no more than reproduce the familyto the advantage of, or on the demand of, a form of State control organized by a State apparatus"; there is no foundational model that can beprojected onto all levels of society, but rather different strategies thatallow relations of power to take on a certain coherence. 3 In La Volonte desavoir, with more conceptual precision, Foucault explicitly understandspower in terms of a multiplicity of relations of force, of incessant tactical struggles and confrontationsthat affect the distributionandarrangement of these relations of force, and of the strategies in whichthese relations of force take effect, with their more general lines ofintegration, their patterns and crystallizations. 6 And the nominalismadvocated in La Volonte de savoir is present in practice in Psychiatric

xviINTRODUCTIONPower: power is "the name that one gives to a complex strategic situationin a given society."7The stakes of this nominalism are evident in one of the firsttheoretical claims about power that Foucault makes in Psychiatric Power,a claim that, despite its apparent simplicity, already requires an entirereelaboration of our conception of power:. . . power is never something that someone possesses, any morethan it is something that emanates from someone. Power does notbelong to anyone or even to a group; there is only power becausethere is dispersion, relays, networks, reciprocal supports, differences of potential, discrepancies, etcetera. It is in this system of dirferences, which have to be analyzed, that power can begin tolunction. 8This claim is the basis of Foucault's later insistence on "the strictly relational character of relationships of power" (and of relationships of resistance), the fact that power "is produced at every moment, in everypoint, or rather in every relation Irom one point to another." 9 Foucaultwas never interested in providing a metaphysics of Power; his aim was ananalysis of the techniques and technologies of power, where power isunderstood as relational, multiple, heterogeneous, and, of course, productive. 10 Foucault went so far as once to proclaim, "power, it does notexist" so as to emphasize that, from his perspective, it is always bundlesof relations, modifiable relations of force, never power in itself, that is tobe studied—that is to say, to render the exercise of power intelligible,one should take up the point of view of "the moving base of relations offorce that, by their inequality, continually lead to states of power, butalways local and unstable."" As late as 198 7 i, when the focus of his interests had already shifted, he stressed this point yet again: "I hardlyemploy the word power, and if I occasionally do, it is always as a shorthand with respect to the expression that I always use: relations ofpower.I believe that it is precisely this relational conception ol power, withall ol its accompanying instruments of analysis, that allows Foucault togive his extraordinary historical reinterpretation ol the problem ol

IntroductionXVllhysteria at the conclusion of Psychiatric Power. When in the final part ofhis lecture of 6 February Foucault takes u p Charcot's treatment of hysterics and what he names "the great maneuvers of hysteria," heannounces the angle of analysis he will adopt: "I will not try to analyzethis in terms of the history of hysterics any more than in terms of psychiatric knowledge of hysterics, b u t rather in terms ol battle, confrontation, reciprocal encirclement, of the laying of mirror traps by whichFoucault means traps that reflect one another], of investment andcounter investment, of struggle for control between doctors and hysterics."1*All of the terms in this description answer to his new analytics of power,with its "pseudo military vocabulary," that will provide the frameworkfor his examination of a wide variety of historical phenomena duringthe 1970s.1H And when he sets aside the idea of an epidemic of hysteria( a scientific-epistemological notion) in favor of an analysis focused on"the maelstrom of this battle" (le tourbillon de cette bataille) that surrounds hysterical symptoms, one cannot help but hear an anticipation ofthe last line of Surveiller el punir where Foucault tells us that in thoseapparatuses of normalization that are intended "to provide relief, tocure, to help" one should hear "the rumbling of battle" (/e grondemenl dela balaille)P It is this rumbling, this maelstrom of battle that Foucault'sperspective renders visible, a struggle that is effaced in a purely epistemological analysis and that is left out of sight within a theory of powerbuilt on a juridical and negative vocabulary. (Hence the way in whichthe "repressive hypothesis" renders imperceptible the multiplicity ofpossible points ol resistance.) To take just one example, Foucault's analytics restores this relational dimension of battle to the great problem ofsimulation that was so crucial to the history of psychiatry; it enables himto treat simulation not as a theoretical problem, but as a process bywhich the mad actually responded to psychiatric power, a kind of "antipower," that is a modification ol the relations ol lorce, in the face ol themechanisms ol psychiatric power—thus the appearance ol simulationnot as a pathological phenomenon, but as a phenomenon of struggle. 16As a result, lrom this point of view, hysterical simulation becomes "themilitant underside the militant reverse side] ol psychiatric power"and hysterics can be seen as "the true militants ol antipsychiatry." 1 'Moreover, the elaboration of this microphysics of power does not require

xviiiINTRODUCTIONFoucault to ignore the epistemological dimensions of the history ofpsychiatry, the discursive practices of psychiatric knowledge. O n thecontrary, it allows him to place these practices within a political historyof truth, to reconnect these practices to the functioning of an apparatusof power, to link them to a level "that would allow discursive practice tobe grasped at precisely the point where it is formed." 18 Psychiatric Powercan be read as a kind of experiment in method, one that responds in historical detail to a set of questions that permeated the genealogical periodof Foucault's work:. . . to what extent can an apparatus of power produce statements,discourses and, consequently, all the forms of representation thatmay then [.] derive from i t . . . How can this deployment ofpower, these tactics and strategies of power, give rise to assertions,negations, experiments (experiences ), and theories, in short to agame of truth? 1 9At the very end of his course, when Foucault returns to the relations ofpower between hysteric and doctor, to hysterical resistance to medicalpower, the scene of sexuality is center stage. But the introduction of sexuality into this scenario does not derive from the "power" of the doctors, but rather from the hysterics themselves, as their putting into playof a point of resistance within the strategic field of existing relations ofpower. As a counter attack to the medical need to find an etiology forhysteria that will give its symptoms a pathological status, and morespecifically (given the distributions of power-knowledge that surroundthe hysterical body) to find a trauma that will function as a "kind ofinvisible and pathological lesion which makes all of this a well and trulymorbid whole," the hysteric will respond with the counter maneuver ofa recounting of her sexual life, with all of its possible traumatism,thereby effecting a redistribution of force relations and a new configuration of power. . . w h a t will the patients do with this injunction to find thetrauma that persists in the symptoms? Into the breach opened bythis injunction they will push their life, their real, everyday life,

Introductionxixthat is to say their sexual life. It is precisely this sexual life thatthey will recount, that they will connect u p with the hospital andendlessly reactualize in the hospital. 2 0And Foucault draws the following remarkable conclusion, which needsto be underlined and related, after the fact, to the context of his laterhistory of sexuality:It seems to me that this kind of bacchanal, this sexual pantomime,is not the as yet undeciphered residue of the hysterical syndrome.My impression is that this sexual bacchanal should be taken as thecounter-maneuver by which the hysterics responded to the ascription of trauma: You want to find the cause of my symptoms, thecause that will enable you to pathologize them and enable you tofunction as a doctor; you want this trauma, well, you will get allmy life, and you won't be able to avoid hearing me recount my lifeand, at the same time, seeing me mime my life anew and endlesslyreactualize it in my attacks!So this sexuality is not an indecipherable remainder but thehysteric's victory cry, the last maneuver by which they finally getthe better of the neurologists and silence them: If you want symptoms too, something functional; if you want to make your hypnosis natural and each of your injunctions to cause the kind ofsymptoms you can take as natural; if you want to use me todenounce the simulators, well then, you really will have to hearwhat I want to say and see what I want to do! 21This victory cry or the hysteric, although a genuine cry of victory, is nota definitive cry. Like all triumphs within the field of mobile andreversible power relations, one can be sure that it will be met by furthertactical interventions, actions intended to modify the new disposition offorce relations, rearranging yet again the existing relations of power. If itis the hysteric herself who, from within the field of power relations,imposes the sexual body on the neurologists and doctors, these latter,according to Foucault, could respond with one ol two possible attitudes.They could either make use of these sexual connotations to discredit

xxINTRODUCTIONhysteria as a genuine illness, as did Babinski, or they could attempt tocircumvent this new hysterical maneuver by surrounding it once moremedically—"this new investment will be the medical, psychiatric, andpsychoanalytic take over of sexuality." 22 History has taught us that thesecond response would be the triumphant one. And the first volume ofFoucault's history of sexuality picks up the battle where Psychiatric Powerleft off, with the codification of scientia sexualis and the solidificationof the apparatus of sexuality, with a new medical victory cry in favor ofsexuality. Indeed, the "hysterisation" of women's bodies is one ofthe four great strategic ensembles with respect to sex that Foucault singlesout as having attained an historically noteworthy "efficacity"the order of power and "productivity" in the order of knowledge.23inTheeffects of an initially disruptive recounting of her sexual life by thehysteric will be reorganized by means of the constitution of a scientificmodality of confession; the traumas of sexuality will become atproduceour27subjection. ' If Charcot could not see or speak of this sexuality, the laterhistory of psychiatry would find it everywhere, would insist on puttingsex into discourse, would enjoin its patients to speak of their sexuality.When the science of the subject began to revolve around the question ofsex, the hysteric's victory was effectively countered by new tactics andstrategies of power, and the reactualization of one's sexual life wasdivested ol its potential ol resistance and became a practice now crucialto the func

treatment" of idiots: Seguin. The process of confinement and the stigmati\ation of the dangerousness of idiots. Recourse to the notion of degeneration. ten 23 JANUARY 1974 233 Psychiatric power and the question truth: of questioning and confession; magnetism a