Transcription

Issues in Business Management and Economics Vol.1 (6), pp. 148-162, October 2013Available online at http://www.journalissues.org/IBME/ 2013 Journal IssuesISSN 2350-157XReviewIdentifying and minimizing risks in the changemanagement process: The case of Nigerian bankingindustryAccepted 7 October, 2013Muo, IKDepartment of BusinessAdministration,Olabisi Onabanjo University,Ago-Iwoye, Nigeria.Author E-mail: muoigbo@yahoo.comTel.: 2348033026625This paper examines the numerous imposed and voluntary changes thathave occurred in the Nigerian banking industry in the past three decadesand identifies the risks associated with the management of those changes.These risks include failure, corporate death, succession, operational policy,infidelity, political and country risks. It also highlights the strategies formanaging and minimizing these risks to include thorough planning andexecution, stakeholder mapping, strategic control, proactive successionmanagement and key-man insurance. The paper concludes that it isimportant for organizations to be aware of change risks, pay particularattention to people issues and continuously scan the environment so as todetect early warning signals. Ultimately, the human element is more criticalthan technology and processes, while an Organisational Behaviourperspective is more imperative rather than focusing solely on facts andfigures.Key words: risk, risk-management, change management, central bank of Nigeria,banking industryINTRODUCTIONBanks and banking are critical to the socio-economicwellbeing and stability of any economy. This is becausetheir efficient fund intermediation oils the wheel ofeconomic development (Nwankwo, 1991). Banks lend athigher maturities, thereby, facilitating capital projects;facilitate payments and transactions, thus promotingcommerce, provide liquidity to markets and reduce thecost of capital, and help firms to manage risks like : suddenswings in exchange rates. The banking sector in Nigeria hasbeen playing these roles in the past 119 years withcommendable successes; though there are also reasonableopportunities for improvement (Muo, 2003). The StructuralAdjustment Programme of 1986 was the first majorfinancial reengineering that fundamentally altered thefeatures and fortunes of the Nigerian banking industry. Itcame along with a basket of measures that promotedderegulation, liberalization of licensing, establishment ofother financial institutions and regulatory overhaul. Therewas the advent of universal banking in 2001, after whichthe banks transformed into being ‘all things to all men’through the super-market model. But the next major leap inthe Nigerian banking industry was the consolidationprogramme of 2004, which raised the shareholders fund toa minimum of N25bn when many banks were still belowN2bn (Soludo, 2004). When the transition ended onDecember 31, 2005, Nigeria had 25 new and not so new‘mega-banks’ in place of the 89 that had hitherto existed. Tocross the N25bn hurdle, some banks merged; some wereacquired and some stood alone. To meet the N100bn capitalthreshold for foreign reserve management and in line withan emerging riotous competitive tempo, some of the banksraised more funds from the capital market; a trend that gotso worrisome that the CBN had to intervene to stop it.Furthermore, Nigerian banks expanded locally andinternationally, establishing full-fledged physical presenceoverseas and consolidated their dominance of the WestAfrican banking landscape as at 2008 (Table 1) .They alsomaintained a significance presence in Africa where theywere 7 out of the top 25 banks (Zenith-7th, First Bank-8th,Guarantee Trust Bank-11th, Access Bank-15th, United

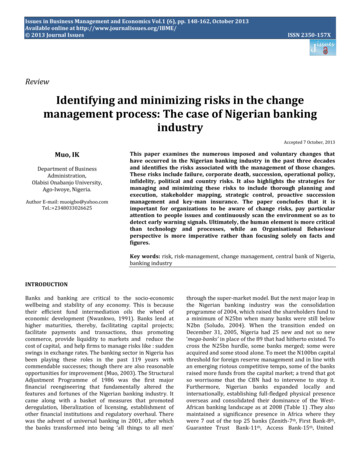

Issues Bus. Manag. Econ.149Table 1. West Africa’s top twenty banks as at 2008Regional Rank1234567891011121314151617181920African h BankOceanic BankIntercontinentalAccess BankGTBUBAFCMBUBNFBNEcobank TransDiamondStanbic IBTCEcobank NigFirst InlandBank PHBSpring BankNig. Intl BankFidelity BankSkyebankAfribankDate of ResultsJune 08Sept 07Feb 08Feb 08Feb 08Sept 07April 08Feb 07Feb 07Dec 07April 07Dec 06Dec 07April 07June 07Dec 05Dec 06June 07Sept 07March tal[ 292284267263234233221Assets[ 8642640155630011052872170635631428Source: African Business, October, 20087 of these Nigerian banks have been lost to the ‘whirlwind’ as at January, 2012! Details as we proceedBank for Africa-16th, Fidelity Bank-17th and Skye Bank-24th(Banker Magazine, 2012). This trend has been described asthe emergence of regional banking groups in Africa; mostlybased in South Africa and Nigeria (Christensen et al., 2006).Another wave of reforms was also unleashed in 2008,which involved dismissal of the executive management ofbanks, injection ofN620bn into liquidity-challenged banks,and introduction of a new banking model among others.This era has been characterized by multiplicity ofregulatory interventions and banks have been continuouslyadjusting and readjusting to these new realities andengaging in strategic change initiatives.Businesses operate under conditions of uncertainty; theuncertainty that expected outcomes may not materializedue to unforeseen exigencies. This uncertainty is thefoundation of the array of risks which every businesscontinually faces. Banks, as a peculiar type of business thatdeal in cash and have the singular ability to create money,are fundamentally built on trust and confidence. In additionto general business risks, banks have their own peculiarrisks. Risks faced by other businesses also take differentdimensions in the banking industry. Thus, while liquidityand reputational risks affect every organization, in thebanking industry, they may lead to runs and outrightclosure. One of the risks that has become very significant inthe Nigerian banking arena - as a result of all theaforementioned developments- is the change risks; risksthat arise from voluntary or imposed changesThe objectives of this paper are: to review the changesthat have occurred in the Nigerian banking industry in thepast three decades. To identify the risks associated with thechange process and suggest ways of managing these risks.The paper is divided into six parts: introduction, conceptualclarifications and literature review, Nigerian banks andcontinuous changes, risks in the change managementprocess, managing of change risks and conclusion.Conceptual clarifications and literature reviewRisks and risk managementDecisions are taken under conditions of uncertainty andimplemented in the future where unpredictability is thenorm. Consequently, there are chances that expectedoutcomes may not materialize. Deviation from the expectedis always a possibility but what matters is the extent of thatpossibility, which is probability. In plain terms, riskexposure is the probability of loss arising from variationsbetween expected and actual outcomes. A decision ortransaction is deemed riskier, if the probability of suchlosses is high, especially if such losses have life-threateningconsequences for the organization. Organizations areexposed to risks for the mere fact of being in existence,because of the philosophy of the management, their typesof business and the environment in which they operate.There is direct relationship between risks and rewards,because, riskier businesses are generally more profitable.Organisations thus, manage risks by deciding which ones toassume and which ones to avoid, and how to mitigate therisks, including the ones they cannot anticipate. Riskmanagement is all about reducing the likelihood ofoccurrence of activities which will have negative outcomes

Muoon the business through the use of certain tools andtechniques (Adebonojo, 2009). Risk management is anattempt to minimize the probability of losses, createalternative plans of action and minimize the impact of theserisks, which are a normal part of the business process. It isalso defined as the identification, assessment andprioritization of risks followed by coordinated andeconomical application of resources to minimize, monitorand control the probability and /impact of unfortunateevents or maximize the realization of opportunities(Banjo,2011). In managing risks, one must bear in mind, the 3-foldnature of risk management: Risks must be identified beforethey are measured and only after the impact has beenevaluated can we decide on the most effective method ofcontrol. The goal of risk management is not necessarily toreduce risks; it is really to establish a set of policies andmanagement techniques to measure, monitor, and controlrisks (Delaney, 2007).Kaplan and Mike (2012), recognize three broadcategories of risks:i) Preventable risks- these are controllable and ought tobe eliminated or avoided;ii) Strategy risks: risks voluntarily accepted in theprocess of trying to generate superior returns; these are notinherently undesirable and they are not managed throughrules based control models andiii)External risks: caused by natural disasters andpolitical/macroeconomic shifts; natural and economicdisasters with immediate impact, geopolitical andenvironmental changes with long term impact andcompetitive changes with medium term impact includingdisruptive technologies and strategic moves.Banjoko (2011) on the other hand classifies risks as pure,speculative, dynamic, static, fundamental, particular, andfinancial or downside. Effective risk management bringsnumerous benefits to the firm and its shareholders, thestakeholders and the society at large and the most obviousis that the business continues to exist to fulfil its economicand social roles in the societyRisks are thus, quantified and managed within thecontext of well coordinated frameworks. Common riskmanagement tools include scenario building, sensitivityanalysis, Monte Carlo simulation and option pricing, whichare offshoots of games and chaos theories and otheradvances in probability sciences. However, the broadmethods of dealing with risks are risk avoidance andassumption, loss prevention and reduction, risk transferand regular risk survey to determine which one to assume,avoid or transfer. Nonetheless, risk management has notalways been a scientific affair, because in the days of old,decisions (and the attendant risks) were guided bysuperstition, blind faith, hunches and incantations(Bernstein, 1996). The elaborate apparatus of riskmanagement facilitated by super-computersandmathematical models have eventually metamorphosed intoa culture and a new religion. This quantification of risks hascreated some lethal dangers for businesses and the society,150especially, the arrogance of quantifying the unquantifiableand increasing- rather than minimizing -risks (Bernstein,1996). Thus, while risk management has become scientific,it is imperative to guard against being ensnared by figures,charts and models which are soulless tools and mere meansto an end.An overview of general business and banking risksGeneral business risksEvery business faces an array of multidimensional andinterconnected risks in its efforts to create value. Theserisks include: market, political, reputation/confidence,financial, ICT, information, succession, credit, operations,regulatory and change risks. Of course, the nature ofbanking will automatically change the nature and impact ofthese risks. Succession risk is the likelihood of anorganization having a failed succession programme; havingan unsuccessful successor, one who leaves before he hassettled down or is rejected by the dominant stakeholders.In this knowledge economy where information moves atthe touch of a button, information risks are also asthreatening as the conventional ones (Johnson, 2005), andso are other newer forms of risks like: political risks (Bach,2005), project risks (Reyck, 2005) and environmental risks.But one of the most critical risks is strategic risk, which isan array of external events and trends that can devastate acompany’s growth trajectory and shareholder value(Slywotzky and Drzik, 2005). They take a variety of formsnew technology, shift in market or customer loyalty - andbusinesses that successfully manage these risks becomerisk-shapers; they are both aggressive and prudent inpursuing new growths.Banking risksBanking is a particularly risky business, especially; as bankshave extended their services to all aspects of the capitalmarket and these include newer types like Reputational,Confidence, and Leadership risks. A risk prioritizationexercise by Arthur Anderson in 2001(cited in Umoh, 2003)identifies the first ten as: computer, human resources,credit default, regulatory, customer satisfaction, ITinfrastructure, liquidity, industry and leadership risks inthat order. Note that computer and human resources riskscame before credit, fraud and liquidity risks. Somecommon bank risks are tabulated in Table 2.E-banking risks also deserve special mention, and they areinterlinked with other conventional banking risks operational, technology infrastructure, security, and ,reputational and legal. Common approaches to measuringand managing these banking risks include: standardssetting and financial reporting, position limits and rules,investment guidelines and strategies: and incentiveschemes (Samtomero, 1997).

Issues Bus. Manag. Econ.151Table 2. Common Bank RisksS/NType of rrency structure68Balance sheet structureIncome structure andprofitabilitySolvency/capitaladequacy9Country & Transfer10Legal11Reputational7Brief DescriptionRisk that party to a loan agreement will not be able or willing toservice the loan[interest/capitalRisk of bank having insufficient funds on hand to meet its currentobligationsRisk of change in interest rate that will have adverse effect on banksincome and/or expensesCapital loss resulting from adverse market price movements relatedin investment in commodity, equity or debtsRisk of adverse exchange movements due to mismatch betweenforeign receivables and payablesRisks resulting from the structure and composition of banks assetsand liabilities and off-balance sheet positionsRisk that a bank does not have enough income to cover its expensesand maintain capital adequacyRisk of bank having insufficient capital to continue operations andnon-compliance with regulatory capital standardRisk arising from economic, social and political environment in theborrowers home country[country risk] and the risk present in loansthat are not denominated in the borrowers local currency[transferrisks]Risks that a banks contract or claims will be unenforceable or thatthe court will impose judgments against it; risks of legal uncertaintydue to lack of clarity of laws in localities in which the bank doesbusinessRisk that problems in a bank can cause customers, creditors andcounterparties or markets to lose confidenceSource: Nnanna (2003) today’s Banking Risks and Current Regulatory and SupervisoryFramework Bullion Vol.27, No.3, July/September; p30There are also some risks associated with the increasinglyinternational and cross-border operations of Nigerianbanks. These cross - border risks include : HigherContagion Crises/Risks- the transmission of a shockaffecting one bank or a group of banks to other banks orthe entire banking sector (Mauro and Yafeh, 2007) ;International Financial Centre is a risks in which the banksand the banking system suffer immensely from anyfinancial crises because of the concentration of financialactivities in the environment just as it happened to the cityof London and UK in The Great Contraction of 2008-2009(Rogoff, 2009) ; Market Integrity Risks;ForeignExchange/Currency Risks- beyond the basic forex risks;Political/Country Risks - which may be macro or micro(Eitman et al., 1998) and depends on the cultural,administrative, geographical and economic‘distance’between the bank in question and the host country(Johnson et al.,2008 ;Ghemawat,2001 ) . Others include:Human Resources (HR) Risk - because the bank has to workwith and through literally unknown people with differentwork culture, orientation and banking habits. HR risksbecome more manifest whenever a wide gulf existsbetween the home and host banking environment, humancapital stock and culture. Next is: Super Bank and Too-BigTo-Fail Risks, because as they expand across borders theirsystematic importance increases and their monitoringability dwindles, thereby, putting their entire operationsand continued existence at risk .Change and change managementOrganizations deliberately change their strategies, culture,processes, procedures or structures so as to directlyimprove their economic performance or to improve theirability to perform. This indirectly impacts their economicperformance. Beyond these deliberate efforts (and most ofthese efforts are due to some other factors like competition,customers, technology and environmental realities),organizations are also compelled to change certain aspectsof their operations by regulatory authorities. In the lattercase, they do not have any choice as to the objective of thechange but they may have various options and routes in theprocess of complying with these directives. Changemanagement refers to how organisations manage thisprocess of deliberate or imposed changes articulation/initiation, take-off, execution, evaluation andreview.Padro de Val and Fuentes (2003), define organisationalchange as an ‘empirical observation of variations in shape,quality or state over time after the deliberate introduction

Muoof new ways of thinking, acting and operating with the aimof adapting to the environment or improving performance’.This phenomenon may be assessed in terms of the extent ofthe organizational change or the speed at which the changeoccurs. Organizational change is also seen as the movementfrom the existing plateau toward a desired future state inorder to increase organizational efficiency andeffectiveness (Cummings and Worley, 2005; George andJones, 2002). Such changes may be sporadic or ongoing asorganizations react to external forces for change or as apart of self-imposed improvement initiatives (Mowart,2002).There are several ways of classifying organisationalchanges. It may be in terms of the degree of change or thespeed of change. Whether the organization designed thechange itself or it was imposed on it. Whether it imitatedothers and the way and manner it was articulated withinthe organization. Whether the management adopted a tell(imposed) or a sell (consultative) approach in articulatingand announcing the change. It can also be taken from theangle of how the industry in its entirety changes. Thus,change may be radical, progressive, creative orintermediating -depending on how it threatens theindustries core assets and activities with obsolescence(McGahan 2004); sustaining (evolutionary) or disruptive(revolutionary) (Christensen and Overdorf, 2000);dramatic - championed by the leaders; systemic championed by the staff managers or organic- championedby rank and file, which may lead to revolution, reforms orrejuvenation (Huy and Mintzberg, 2003).Other classifications of change include: vision led andproblem driven changes (Fradette, 1998); fundamental ortransformational (addressing big-picture issues likestrategy, culture, strategy) and transitional or transactional(concerned with everyday issues) like structure, processes,needs (Beckhard and Harris, 1987). Others are:developmental (improvement on current operations),transitional (replacing existing processes or methods) ortransformational (occurs after transitional; moving into andoccupying the new state) (Olufade, 2010); convergent,radical, evolutionary and revolutionary (Cummings andWorey, 2005). Next are: evolutionary, incremental, firstorder changes (small changes, improvements on thepresent situation) or transformational, strategic, secondorder changes (change of essential framework that affectsoperational capabilities) ( Padro de Val and Fuentes, 2003).Adaptive change - which occurs when changes in societies,markets, customers, competition and technology forceorganizations to clarify their views, develop new strategiesand learn new ways of operating (Heifetz and ralized) change; (Dragos, 2009) incrementalinnovation( small improvements in existing products andprocesses to operate more efficiently and deliver greatervalue to customers), architectural innovations( applyingtechnological or process advances to fundamentally change152some component or elements of their business) anddiscontinuous innovations( radical advances thatprofoundly alter the basis for competition in an industryoften rendering ways of working obsolete) (O’Reilly andTushman, 2004).Nigerian banks and continuous changesNigerian businesses have been experiencing changes as inother parts of the globe. However, no sector hasexperienced that change as the Nigerian Banking industry,which has been subjected to rapid regulatory quakes since1986, with the enthronement of Structural AdjustmentProgramme (SAP) by the military administration underBabangida . Before the advent of SAP, the Nigerian bankingindustry was characterized by an admirable calmness andthe only worry then was whether the monetary policyregime was tight or loose. It was a control-prone era andthe banks operated as dictated by the annual monetarypolicy and foreign exchange circulars which literarilycontrolled every banking process and policy (Onwumere,2005). SAP changed all that by introducing a regime thatshook the banking industry to its foundation. Every aspectof banking, except opening of branches, was deregulated.New institutions and laws were introduced and an unholytrinity of privatization, commercialization and deregulationbecame the economic mantra. More banks were licensedand efforts were also made to wean the banking sectorfrom dependency on public sector deposits to the extentthat MDAs were once ordered to open retail accounts withthe Central Bank of Nigeria (Muo, 2003).The entire banking system was turned ‘upside down’ asbanks made efforts to comply with the new, strange regime.The new order also unleashed a competitive volcano withinthe industry especially, between the old and newgeneration banks. The process led to riotous competitionand regulatory laxity as several initiatives were beingintroduced simultaneously. The operators allowed theirgreed to overrun their sense of judgment while people gotto positions they were not qualified for because of thedearth of capable professionals and people were promotedbeyond their competence. The Peter Principle was at workas managers were promoted to their level of incompetenceor rather, beyond their level of competence (Peter, 2011).Policy summersaults and government indebtedness andinterference in banking operations were also veryprevalent and all this culminated in distress that ravagedthe industry and the entire economy (Ebodaghe, 1996,NDIC, 2001, Fadiran, 2009). The process of managing thecontagious distress led to a lot of regulatory interventionsin form of hitherto unknown rules and actions especially bythe NDIC, which itself was the outcome of SAP and allieddevelopments. By the time the banking distress ended andthe remaining banks tried to pick up the pieces of what wasleft of the industry, the problem of round-tripping andother unholy practices emerged. Round-tripping isan

Issues Bus. Manag. Econ.153unethical and indeed illegal process of sourcing foreignexchange at the official market for supposedly genuinetransactions and then selling it at the parallel market at avery high premium. Again, another round of regulatoryquick-fixes was introduced to contain the situation.The next major regulatory intervention was unleashed in2001 in the form of the universal banking policy which ledto a wholesale reconfiguration and banks had to scrambleto meet the new operational imperatives. Under thisscenario, banks had the right to engage in all or someactivities such as: normal banking activities (current,savings, and deposit accounts, cheque collection andpayment, credit facilities and forex transaction) to beregulated by the CBN; clearing house activities to beregulated by Nigerian Interbank Clearing System andNigerian Automated Clearing System; Capital MarketActivities (issuing, underwriting and advisory services) tobe regulated by Securities and Exchange Commission andthe Nigerian Stock Exchange; and insurance activities(agency brokerage, underwriting; lost adjusting andreinsurance) to be regulated by National InsuranceCommission. The Central Bank was the overall regulator. Bythis policy, the banks had actually become all things to allmen and the pigeonholing of financial services into severalcompartments was abandoned and the financialsupermarkets model became operative (Muo, 2012).Of course, it must be agreed that the merchant banks hadlobbied relentlessly to be allowed to access cheap retaildeposits-just like the commercial banks and this clamourwas satisfied by the Universal Banking framework. Thiswas also in tandem with developments in the globalbanking industry. Banks had to brainstorm to conform tothis regime and that was as they were just emerging fromthe tremor caused by distress and related problems. By thistime, the classification of the banking industry had takencomplicated and confusing dimensions as we had the oldgeneration banks, new generation banks, millenniumbanks, (like Platinum and Reliance Banks), convertedbanks (like Intercontinental and Metropolitan banks), andresuscitated banks (like National and African Continentalbanks) (Muo, 2007).Before the banks become fully attuned to the universalbanking mode, the Soludo-led management emerged withthe 13-point agenda, which included the thousand-foldincrement in capital requirements (Soludo, 2004). Thisresulted in consolidation and the reduction in the numberof banks from 89 to 25. While this was a strategic andcomprehensive initiative to overhaul the Nigerian bankingindustry and equip it for the emerging challenges, it wasstill another regulatory tsunami inflicted on an industrythat was just trying to settle down to the dictates of therecently introduced universal banking. Banks and bankerswere once more thrown into incalculable confusion in aneffort to meet another round of strange and hithertounimaginable regulatory requirements.Just as the banks were trying to settle down to thedictates of consolidation and at most expected further finetuning and smoothening of rough edges, Lamido Sanusisucceeded Soludo as the Governor of CBN. And within thefirst year of his tenor, the Nigerian banking industrysuffered the greatest regulatory violence in its history. Theboard and management of 8 banks were dismissed with theCBN appointing interim board and management, injectingN620bn to support the banks (CBN, 2009). List of debtorsof the affected banks was released; the police, Economicand Financial Crimes Commission and the courts weredeployed in controversial efforts to recover the debts. TheCBN also cancelled the Universal Banking programme andintroduced a new banking model (CBN, 2010a). Thus, in asingle reform package, the universal banking programme(2001) and consolidation programme (2004) werecancelled while narrow-banking option (separating retailfrom investment banking), modular design option(ensuring that separate businesses are conducted byseparate vehicles) were simultaneously adopted. The AssetManagement Company of Nigeria, a ‘bad bank’, was alsoestablished (FRN, 2010, Elueni, 2011, Iyatse, 2012).This is also being done in an era of unparalleleduncertainty. While the previous programmes had cleardirections and operators knew where they were heading to,the Sanusi era was initially characterized by the as-thespirit-directs banking. Even the Federal Government didnot know the direction of the CBN programmes and thatwas why the Ministry of Finance publicly demanded thatthe CBN should provide a blueprint (Ewulu, 2012). Owoh(2013) notes that there are no reform master plans oromnibus roadmap, while the reform targets benchmarksand the means/costs associated with them are not knownwith ad-hoc pronouncements the order of the day. It alsoappeared as if there was a deliberate policy to upturn allthe policies of the previous CBN management. Theseinclude the uniform minimal capital base; the totalorganizational restructuring of CBN that increasedoperating departments to 25 barely a year after thepredecessor had reduced them to 17; recalling of residentexaminers and altering the guidelines for the registration ofvarious classes of Bureau de Changes for forex businesses.There were other developments as new regulatory regimeswere introduced. The tenure of bank CEOs were limited to10 years, (Olajide and Fodeke, 2010), the tenure of boardmembers and the ownership of foreign subsidiaries werealso streamlined. These changes also had other impacts.The banks that had hitherto overran the West Africanbanking environment and were making serious inroads intothe rest of Africa had to suspend further foreignexpansions, sell off existing ones or restructure theownership and management models of these banks (CBN,2012b). Other changes include the compulsory retirementof CEOs who had spent up to 10 years in office (this affectedZenith, UBA, and Skye banks), tenure limit of 12 years fornon executive directors and compulsory replacement ofexternal auditors after ten years. It should be noted that in

Muothe last two cases, the CBN merely activated dormantprovisions.In the 13 months between August 2011 and September2012,the Nigerian banks witnessed the followingregulatory initiatives: the take-off of Islamic banking (Muo,2011), the nationalization of three banks

management process: The case of Nigerian banking industry Accepted 7 October, 2013 Muo, IK Department of Business Administration, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Nigeria. Author E-mail: muoigbo@yahoo.com Tel.: 2348033026625 This paper examines the numerous imposed and voluntary changes that have occurred in the Nigerian banking industry in the past three decades and identifies the .