Transcription

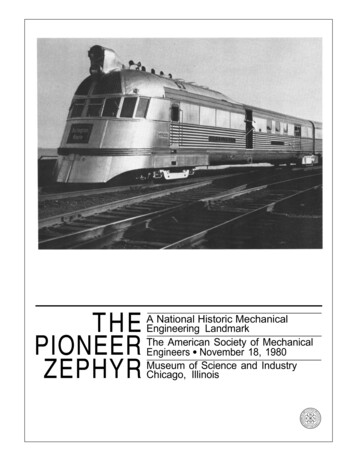

THEPIONEERZEPHYRA National Historic MechanicalEngineering LandmarkThe American Society of MechanicalEngineers November 18, 1980Museum of Science and IndustryChicago, Illinois

NATIONAL HISTORIC MECHANICALENGINEERING LANDMARKTHE AMERICAN SOCIETY OFMECHANICAL ENGINEERS - 1980THE PIONEER ZEPHYR“Each of us can say—as hewould at Plymouth Rock or at Independence Hall—‘it all started righthere.’ And ‘right here,’ to Burlington men, is the specific point inhistory at which this railroadturned its attention from our magnificent steam engines to the earlydiesels. This point is marked by thePioneer Zephyr,” wrote former Burlington Railroad President H.C.Murphy in 1963.Comparing the introduction ofthe Pioneer Zephyr—the world’sfirst diesel-powered, stainless steelstreamlined train—to the landingof the pilgrims at Plymouth Rock,might strike some as grandiose.But as every railroad buff knows,the debut of the Pioneer Zephyrwas, in its own right, that important.For underneath the Zephyr’s brilliant silver exterior lay a revolutionary two-cycle diesel engine thatwould soon replace the traditionalsteam engine, changing forever thenature of the entire railroading industry. The 97½-ton train itself wasan impressive 196 feet of fluted,stainless steel, a lightweight material never before used in the construction of rail cars. Not only wasthe steel beautiful to look at, it alsoheld together better and worelonger than the metals it replaced.Inside the train, the Zephyr provided luxury accommodations today’s rail travelers can only dreamabout.With all those advantages backing it up, the Pioneer Zephyr salvaged the role of the railroad as acarrier of passengers, as well asfreight. In the coming years, thepowerful diesel engines introduced by the Zephyr would prove aformidable match to the burgeoning trucking industry thatthreatened to take away the railroads’ freight traffic.Murphy presented some statis-tics to back up his proud claim thatthe era of diesel railroading startedwith the Burlington’s Zephyr. In1934, the year the Zephyr made itsfirst run, some 50,000 smokebelching steam locomotives werepuffing their way back and forthacross the United States, rackingup 17.8-billion passenger miles and268-billion ton-miles of rail transportation.By 1961, following the PioneerZephyr’s lead, the country had become completely “dieselized.” Approximately 28,500 diesel unitsproduced 20-billion passengermiles and 565-billion ton-miles. Inother words, the diesel-poweredunits were capable of doing almostfour times the work performed bytheir predecessors, the steamlocomotives.In the early days, the advantagesof the dieselized engine were notso evident.

THE RAILROAD VERSUSTHE MODEL TAnyone watching a 1920 Model Tautomobile jerking and backfiringdown the road would find it hard tobelieve that the abject of so muchderision would one day threatenthe very existence of the railroad asa passenger carrier. But that isexactly what happened.In 1924, the Burlington Railroadcarried a whopping 18-million passengers. Only five years later, as theautomobile’s popularity increased,that figure dropped to 13.8-million.And by 1933, in the midst of theGreat Depression, only 7-milliontravelers rode the rails. Passengerrevenues followed a parallel descent. To the amazement of many,the railroad, with a tradition asgrand as any in America, wasslowly being replaced by an armyof 30 mph automobiles.Luckily for the railroad industryand the traveling public, a figureappeared on the scene in the early1930s, with the know-how and determination to build a train to meetthe demands of the 20th centurytraveler. His name was Ralph Budd,and he became president of theBurlington Railroad in 1932.By the time Budd arrived at theBurlington, the automobile hadedged out trains as the favoredmeans of transportation, even forlong distance travel. Budd wasamong the first to admit that “theloss of railway passenger trafficduring the last decade has beencaused by a shifting from the railways to the highway, and not from adecline in total travel. In fact, thetotal passenger one-mile units oftravel have greatly increased.”Budd reasoned that since automobile engineers had derailedthe passenger train, they could bethe ones to put it back on thetracks. As author David Morgannoted in “Diesels West!,” suchthinking implied the use of a kind ofautomotive internal combustionpower instead of the steamlocomotive, upon which the industry had relied for a century.THE FIRST STAINLESSSTEEL-SHOD TRAINOne of Budd’s first moves was tovisit the Edward G. Budd (no relation) Manufacturing Co. inPhiladelphia. The Budd Co. hadbeen the first to produce the allsteel automobile wheel, as well asthe all-steel automobile body. Nowit was ready to tackle passengertrain construction.At the Budd Co. plant, the Burlington president examined a testrail car body incorporating anumber of radical innovations, including a gas engine and rubbertires. Budd immediately dismissedthese alterations as impractical.What caught his attention was thecar’s stainless steel construction.The benefits of the stainless steelrail car were obvious: the materialwas lightweight yet strong, and itlasted almost forever. The problemwas nobody had been able to figureout a way to build stainless steel railcars in a practical shop operation.Fortunately, the Burlington president’s timing was just right. TheBudd Co. had just patented itsDuring the record-setting 1,000-miledawn-to-dusk run from Denver to Chicago inMay 1934, a select group of passengersrelaxed in the Pioneer Zephyr’s roundedsolarium-lounge. One of the passengers(third from left), was Edward G. Budd,president of the Budd Manufacturing Co.that built the all-steel train.newly devised “Shotweld Process.”The system allowed rivetless seamsof stainless steel to be joined without damaging its corrosionresistant qualities. At the sametime, it provided a joint strongerthan the steel it held together.Ralph Budd knew a good product when he saw one. He decidedthis would be the material for thenew train he set out to build to recapture the rail passenger market.On June 17, 1933, barely a yearsince he first stepped into office,Ralph Budd signed a contract withthe Budd Co. to construct a trainout of stainless steel. The firm wasgiven virtually free reign in the design of the train.Now Budd needed a power unitfor his stainless steel train, to replace the hopelessly outdatedsteam engine. As usual, Budd gotwhat he went after.DIESEL POWER ERADAWNSThe expertise of no less thanthree firms was brought to bear onthe problem of building a two-cyclediesel engine to meet the demandsfor train engines with increasedhorsepower. The work was led bythe General Motors Co., which wasgreatly aided by the company’s1930 acquisition of the Winton Engine Co. and rail carbuilderElectro-Motive Co.But it was Charles F. Kettering,General Motors’ vice president ofresearch, and the engineering staffof Winton Engine Co., that led theproject to a successful conclusion.In the late 1920s, Kettering beganwork on the two-cycle diesel engine, which eventually would become an integral part of thePioneer Zephyr. His aim was to design a lightweight power unit withimproved response and lower costper horsepower than the availableengines.A period of great productivity followed the 1930 merging of theGeneral Motors, Winton-Engine,and Electro-Motive companies.During that time, a number of significant engineering contributions

The Zephyr was a hit attraction at the 1934 World’s Fair in Chicago. The silver, streamlinedtrain was responsible for reviving the public’s interest in rail passenger service at a timewhen the passenger train seemed almost a thing of the past.The Pioneer Zephyr was the first streamlinedtrain to carry the U.S. mail. At station stops,passersby could deposit letters in a specialmailbox built onto the side of the train.were made. The unit injector wasdevised, incorporating the pumping and fuel metering functionsinto a single device to avoid highpressure lines.Two other significant achievements were the application of theengine-driven positive displacement blower for scavenging, andthe development of the weldedsteel crankcase, which enabled areduction in overall weight overcast steel versions.A major turning point occurredin 1933, when the Kettering team’seight-cylinder, 600-hp, 8-201 engine, with a weight-to-power ratioof only 20 pounds per horsepower,was chosen to supply power to theChevrolet exhibit at Chicago’s“Century of Progress Exposition.”While visiting the Fair, RalphBudd came upon the display, andimmediately decided that theIightweight diesel engine wouldprovide the power for his all-new,all-important passenger train. AsBudd saw it, the diesel railroad wasthe railroad of the future—and ifany company could put the dieselengine in a train, it was GeneralMotors.Approximately one year later, onMay 26, 1934, the Pioneer Zephyrseats for 20 passengers.Third and last was a 31-ft. compartment with seats for 40 persons,and a solarium-lounge with chairsfor 12.Prior to the Pioneer Zephyr, thetraveling public knew only ornatebut gloomy railroad car interiors.All that changed with the highstepping Zephyr. Each individualcompartment had a distinctivecolor harmony coordinating wallcolors, window drapes, upholstery,and floor covering.But more important than theZephyr’s looks was the uplifting effect it had on a mid-DepressionAmerica. Said a former PioneerZephyr rider, “I have always felt thatthe Pioneer Zephyr, in introducinga new type of service at a time whenthe Depression was still fresh in ourminds, had a stimulating effect inthat it lifted our spirits and hadmuch to do with reaffirming thefaith of the people in the free enterprise system. True, it was not aworld-shaking event, but it pointedthe way for better things to come.”No. 9900 made its grand debut witha record-setting 1,000-mile dawnto-dusk run from Denver toChicago in 13 hours. Appropriatelyenough, the Zephyr was namedafter the Greek god of the westwinds.The train was powered by a Winton 8-201A 600-hp, two-cycle dieselengine (a revision of the modelRalph Budd saw at the fair), designed to travel at speeds of approximately 110 mph. Not only wasthe Pioneer Zephyr faster andlighter than its predecessors, italso reduced the Burlington’s costof passenger train operation.A new era in railroading historyhad begun.THE INSIDE STORYThe high operating standards ofthe world’s first high speed dieselpropelled, stainless steel three-cartrain were matched by the Zephyr’spainstaking interior furnishings.The first car held the diesel engine, engineer’s cab, a 30-ft. railwaypost office, and space for baggage.The second car carried a largerbaggage compartment, a buffetgrill and, at the rear portion of theunit, a 16-ft. smoking section withPIONEER OF AN ERAFollowing the Zephyr’s first historic run, it made another cross-

country tour covering 222 cities,where it was received by some2-million spectators. The train alsowas a hit attraction at Chicago’s1934 Century of Progress.On Armistice Day 1934, theZephyr went into regular passenger service, serving the Westand Midwest until its retirement.That was only the beginning—for the diesel and for the PioneerZephyr. The train was the star ofradio programs and a hit movie entitled “The Silver Streak.” Itsparked dreams of adventure in theminds of countless small boys andgirls—and of distant places in theminds of their parents.The first million miles of thePioneer Zephyr were celebrated onDec. 29, 1939. On Apr. 10, 1944, theZephyr was the guest of honor at its10th birthday party at Lincoln, Neb.The granddaddy of diesel-poweredstreamlined trains celebrated its20th anniversary of regular serviceat Quincy, III.Finally on May 26, 1960, thePioneer Zephyr pulled up to its finaldestination just outside the EastPavilion of Chicago’s Museum ofScience and Industry, blowing thewhistle on an unparalleled careerthat had spanned 26 years andsome 3.2-million miles. ThePioneer Zephyr is now on permanent exhibit at the Museum.A TRADITION ISESTABLISHEDIn addition to all of its technological achievements, the PioneerZephyr led to a revival of the pub-The Pioneer Zephyr is on permanent exhibit at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry.lic’s interest in rail passenger service. Settled comfortably in thewelcoming arms of the moderntrain, thousands of Americanswatched the nation’s prairies,mountains, and forests fly by.Glamour queens of the era likednothing better than to make agrand entrance into town by rail,greeted by crowds waiting on thestation’s platform.The Pioneer Zephyr spawned afamily of sister Zephyrs, each one atestimony to the Burlington Railroad’s dedication to engineeringexcellence. It was a model for thepassenger trains of competing railroads.Although the Pioneer Zephyr nolonger rides the rails, its name liveson as a symbol of young America’sindustrial genius.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe Diesel and Gas Engine Power Div. of The American Society of MechanicalEngineers gratefully acknowledges the efforts of all who cooperated on thelandmark designation of the Pioneer Zephyr, Chicago, III. A special thank you isextended to the Museum of Science and Industry, the Electro-Motive Div. of theGeneral Motors Corp., and the ASME Rail Transportation Div. and Chicago Sectionfor their assistance.The American Society of Mechanical EngineersDr. Charles E. Jones, presidentJames R. Jones, vice president, power departmentCharles O. Velzy, vice president, industry departmentWarren C. Fackler, vice president, Region VIDr. Rogers B. Finch, executive director and secretaryThe National History and Heritage CommitteeProf. J.J. Ermenc, chairmanDr. R. Carson DalzellProf. R.S. HartenbergDr. J. Paul HartmanRobert M. Vogel, Smithsonian InstitutionCarron Garvin-Donohue, staff director of operationsJill Birghenthal, administratorThe Diesel and Gas Engine Power DivisionFrank J. Pekar, Jr., chairmanWalter R. Taber, Jr., vice chairmanEdwin C. Younghouse, vice chairmanDouglas W. ExlineKarl T. GeocaW. Warren NugentLewis D. ContaThe Pioneer Zephyr is the 54th National Landmark designated by the Society. For acomplete listing of Landmarks, please contact the Public Information Department,ASME, 345 E. 47th St., New York, NY 10017 212/644-7740.HO58

Pioneer Zephyr. His aim was to de-sign a lightweight power unit with improved response and lower cost per horsepower than the available engines. During the record-setting 1,000-mile dawn-to-dusk run from Denver to Chicago in A period of great productivity fol-May 1934, a select group of passengers lowed the 1930 merging of the

![Z W ] } v ] ( ( nce completed, W ] } v W l P ] v P t r õ W ] } v W l P .](/img/56/pioneer-new-client-welcome-2021.jpg)