Transcription

MARSHALLISLANDS

MARSHALL ISLANDSFebruary 2015Disaster Risk Financing and InsurancePCR AFI 2015Country Note

2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development /International Development Association orThe World Bank1818 H Street NWWashington DC 20433Telephone: 202-473-1000Internet: www.worldbank.orgThis work is a product of the staff of The World Bank withexternal contributions. The findings, interpretations, andconclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect theviews of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or thegovernments they represent.The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the dataincluded in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, andother information shown on any map in this work do not implyany judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning thelegal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance ofsuch boundaries.Rights and Permissions****The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because TheWorld Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, thiswork may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercialpurposes as long as full attribution to this work is given.Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights,should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The WorldBank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202522-2422; e-mail: pubrights@worldbank.org.Photo Credits****Photos specifically credited are done so under Creative CommonsLicenses. The licenses used are indicated through icons showcasednext to each image.b 2.0 Attribution /legalcode)bd Attribution No-Derivatives 2.0/legalcode)ba Attribution Share Alike 2.0/legalcode)If not indicated otherwise, photos used in this publication havebeen sourced from the following locations with full rights:World Bank Flickr WebsiteUnited Nations Flickr WebsiteAll non-Creative Commons images in this publication requirepermission for reuse.Cover Photo Credit: Kyle Post / Flickr b//////

MARSHALL ISLANDSPCRAFITable of Contents01 Acknowledgments02 Acronyms and Abbreviations03 Executive Summary05 Introduction07 Economic Impact of Natural Disasters10 Public Financial Management of Natural Disasters11 Post-Disaster Budget Mobilization12 Ex-Ante Practices and Arrangements14 Ex-Post Practices and Arrangements15 Total Response Funds Available16 Post-Disaster Budget Execution18 Domestic Catastrophe Risk Insurance Market19 Options for Consideration20 End Notes21 References22 About PCRAFI23 Annex 130 Annex 231 Annex 3i

MARSHALL ISLANDSPCRAFI01AcknowledgmentsThis note has been prepared by a team led(SPC) through its Applied Geoscience andby Olivier Mahul (Disaster Risk Financing andTechnology Division (SOPAC), the World Bank,Insurance Program Manager, World Bank) andand the Asian Development Bank, with financialcomprising Samantha Cook (Financial Sectorsupport from the government of Japan and theSpecialist) and Barry Bailey (Consultant).Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery(GFDRR).The team gratefully acknowledges the data,information, and other invaluable contributionsThe Disaster Risk Financing and Insurance Programmade by the Pacific Island Countries. Without theiris grateful for the financial support received fromskills and expertise, the compilation of this notethe government of Japan and the Global Facilitywould not have been possible.for Disaster Reduction and Recovery.This note benefitted greatly from the technicalexpertise of the following persons: Franz DreesGross (Country Director Timore-Leste, Papua NewGuinea. and Pacific Islands, World Bank), OlivierMahul (Disaster Risk Financing and InsuranceProgram Manager, World Bank), Denis Jordy (SeniorEnvironmental Specialist, World Bank), MichaelBonte-Grapentin (Senior Disaster Risk ManagementSpecialist, World Bank), Paula Holland (Secretariatof the Pacific Community), and David Abbott(Secretariat of the Pacific Community).Inputs and reviews from Robert Utz, DavidKnight, Kim Edwards, Oscar Ishizawa, RashminGunasekera, Keren Charles, Francesca de Nicolaand Susann Tischendorf greatly enhanced the finalnote. Design and layout developed by Bivee.co.The Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment andFinancing Initiative (PCRAFI) is a joint initiativebetween the Secretariat of the Pacific CommunitySectionA

PCRAFI02Acronymsand AbbreviationsCFACompact of Free AssociationDAEFDisaster Assistance Emergency FundDRFIdisaster risk financing and insuranceDRMdisaster risk managementHFAHyogo Framework for ActionJNAPJoint National Action PlanPCRAFIPacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing InitiativePICPacific Island CountryRFARegional Framework for ActionSIDSSmall Island Developing StatesSOPACApplied Geoscience and Technology Division of SPCSPCSecretariat of the Pacific CommunitySPREPSecretariat for the Pacific Regional Environment ProgrammeTCTropical CycloneUNDPUnited Nations Development ProgrammeUNISDRUnited Nations International Strategy for Disaster ReductionCurrency: US SectionAMARSHALL ISLANDS

PCRAFIMARSHALL ISLANDS03Executive SummaryThe likelihood that a hazardous event willUS 100,000. Consequently the government relieshave a significant impact on the Marshallheavily on donor support to fund post-disasterIslands has risen with the increasing levelsexpenditures.///of population and assets in the urban areasof Majuro and Ebeye. The low-lying atolls areThe Marshall Islands has a maximum amount//////at risk of damage to both assets and people as aof US 15.6 million potentially available inresult of storm surges and tsunamis. In Decemberex-ante instruments to facilitate disaster2008, a state of emergency was declared followingresponse, which is equivalent to 44 percent ofweeks of high seas, which resulted from stormthe recurrent budget in 2013. These contingentsurges coinciding with high tides and two tropicalfunds are composed of US 0.2 million from thedepressions (Marshall Islands Government 2009;contingency budget, US 0.1 million from theUNOCHA 2008). These events caused damage toDAEF, and the maximum payout of US 15.3roads, houses, and other infrastructure on the low-million from the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurancelying atolls of Majuro and Ebeye. Similar events arePilot. It is estimated that there is a 1 percentexpected to become more frequent with climatechance in any year that disaster losses will exceedchange and rising sea levels.the total amount available. However, it shouldThe Marshall Islands is expected to incur, on///average over the long term, annual losses ofUS 3 million due to earthquakes and tropicalcyclones. In the next 50 years, the Marshall Islands///be noted that the risk insurance pilot will releasefunds only if certain pre-agreed upon eventmagnitudes are reached. If the contingency budgetand DAEF alone are considered, there is an 18.6///has a 50 percent chance of experiencing a lossexceeding US 53 million, and a 10 percent chanceof experiencing a loss exceeding US 160 millionpercent chance that funds will be exceeded in anyone year.The government’s post-disaster budget///(PCRAFI 2011).execution process relies on a variety ofThe government takes an ex-ante approachfinancial tools, but the size of the economyto financing the cost of disasters, but thelimits access to immediate post-disaster cashresources available are limited. While theresources. The government has dedicated, yetgovernment has a contingency budget and accesslimited, funds that can be accessed followingto the Disaster Assistance Emergency Fund (DAEF),an event and used effectively; however, not allthe immediate cash available through the formercurrently followed procedures are embeddedis only US 200,000 and through the later onlywithin the financial legislature, including those/////////SectionA

PCRAFI04MARSHALL ISLANDSrelated to the unique requirements of post-disasterfinancing.A number of options for improving disaster riskfinancing and insurance are presented here forconsideration:(a) develop an integrated disaster risk///financing and insurance strategy;///(b) assess the domestic insurance market for///both public and private assets to establishwhat products are currently offered andto determine their level of uptake;(c)///carry out a quantitative analysis to///determine whether contingent creditcould be an effective tool to accessadditional liquidity post-disaster; and///(d) investigate the possibility of establishing///policies for financial assistance to disastervictims in remote communities.///Photo Credit//////Stefan Lins/Flickr b

MARSHALL ISLANDSPCRAFI05IntroductionThe Marshall Islands has a land area of 181km2The Marshall Islands government, in conjunction/// sup /scattered across a collection of 29 atolls andwith the Secretariat of the Pacific Communityfive islands. Most of the atolls and islandsApplied Geoscience Division (SPC-SOPAC), thehave an elevation of less than 6m above seaSecretariat of the Pacific Regional Environmentlevel, including the capital, Majuro, many parts ofProgramme (SPREP), the United Nationswhich are less than 1m above sea level. The low-Development Programme (UNDP) Pacific Centre,lying atolls and islands lie in an expanse of oceanthe United Nations International Strategy forof almost 2 million km2. This scattered geographyDisaster Reduction (UNISDR), and other partners,increases both the time and cost involved in initialhas developed several institutional frameworkspost-disaster response.on disaster risk management (DRM) and climatesup ///According to the 2011 Population and HouseholdCensus, the population of the Marshall Islandschange adaptation at the national, subregional,and international level, including the following: Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) 2005–2015is 53,158.1 The two urban centers, Majuro andEbeye (a small islet on Kwajalein atoll), have Pacific Disaster Risk Reduction and Disasterpopulations of 28,000 and 9,614, respectively.Management Framework for Action (RegionalEbeye has the highest population density in theFramework for Action or RFA) 2005–2015Pacific, equivalent to an estimated 66,750 peopleper square mile; this is higher than the population National Action Plan for Disaster Riskdensity in Tokyo, estimated at 15,619 people perManagement, 2008–2018square mile.2 Marshall Islands Emergency Response Plan,Events in 2013 demonstrated that the2010///Marshall Islands is extremely vulnerable tothe threat of both storm surge and drought. Policy for Climate Change Adaptation, 2006///In May 2013 a statement of emergency was issuedbecause of severe drought conditions in the atolls Joint National Action Plan (JNAP) for DisasterRisk Management and Climate Changeof Mejit and Utrik, located in the north. In contrast,Adaptation, 2011–2014flooding forced the airport on the main island ofMajuro to close on June 25, 2013. The seawallDisaster risk financing and insurance (DRFI) is///that protects the runway broke in four places as aa key activity of the HFA Priorities for Actionresult of high tides and an associated storm surge.4 and 5. The HFA is a result-based plan of actionBoth of these incidents highlight the vulnerabilityadopted by 168 countries to reduce disaster riskof the population and their assets, both publicand vulnerability to natural hazards and to increaseand private.the resilience of nations and communities to///Section01

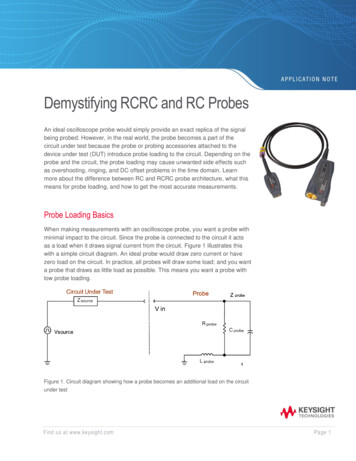

PCRAFI06disasters over the period 2005–2015. In the Pacific,the HFA formed the basis for the development ofthe Regional Framework for Action.MARSHALL ISLANDSto meet post-disaster funding needs withoutcompromising their fiscal balance. This programis one application of the Pacific Catastrophe RiskAssessment and Financing Initiative (PCRAFI).The RFA cites DRFI activities as a key nationalThe Pacific DRFI Program is built upon a three-and regional activity. Theme 4—“Planning fortiered approach to disaster risk financing. Theseeffective preparedness, response and recovery”—layers align to the basic principles of sound publichas an associated key national activity, “Establish afinancial management, such as the efficientnational disaster fund for response and recovery.”allocation of resources, access to sufficientTheme 6 of the RFA—“Reduction of underlyingresources, and macroeconomic stabilization. Therisk factors”—cites the development of “financialthree tiers acknowledge the different financialrisk-sharing mechanisms, particularly insurance,requirements associated with different levelsre-insurance and other financial modalitiesof risk: (i) self-retention, such as a contingencyagainst disasters as both a key national andbudget and national reserves, to finance smallregional activity” (SOPAC 2005). These regionalbut recurrent disasters; (ii) a contingent creditimplementation activities align with the three-tieredmechanism for less frequent but more severedisaster risk financing strategy developed by theevents; and (iii) disaster risk transfer (such asWorld Bank.insurance) to cover major natural disasters. See//////Goal 2 of the Marshall Islands (2007) Nationalfigure 1.///Action Plan for Disaster Risk ManagementThis report aims to build understanding///seeks to “mainstream DRM in planning,of the existing DRFI tools in use in thedecision making and budgetary processes atMarshall Islands and to identify gaps wherenational and local levels.” This goal includesengagement could further develop financialestablishing a sustainable fund for DRM.resilience. The report also aims to encourage peer///The Pacific Disaster Risk Financing and///Insurance Program enables countries toincrease their financial resilience againstnatural disasters by improving their capacity//////exchange of regional knowledge, specifically byencouraging dialogue on past experiences, lessonslearned, optimal use of these financial tools, andthe effect these tools may have on the executionof post-disaster funds.Figure 1 — Three-Tiered Disaster Risk Financing StrategyRisk TransferLow Frequency/High SeverityInternational AssistanceSovereign Risk Transfer(e.g. Cat Bond/Cat Swap, (re)insurance)01Risk RetentionSectionHigh Frequency/Low SeverityContingent Credit LinesInsurance of Public AssetsPost Disaster CreditGovernment Reserves, Contingency Budget / FundsEmergency FundingReconstructionSource: World Bank 2010.

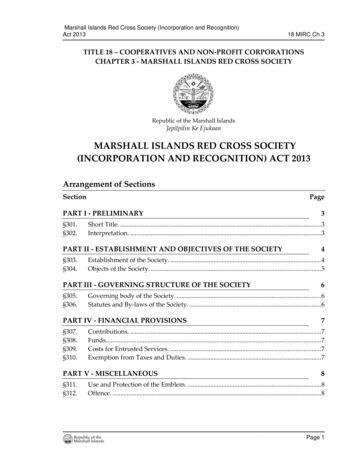

PCRAFIMARSHALL ISLANDS07Economic Impact ofNatural DisastersBetween 1988 and 2008, 18 natural disastersFigure 2 — Building Locations///affected around 12,700 people in theMarshalls Islands. The estimated direct cost ofthese events was US 317 million (SPC-SOPAC2012). Half of these disasters were slow-onset///disasters such as droughts. Droughts have madeaccess to safe water an especially important issuefor the Marshall Islands. Droughts also increase therisk of water-borne diseases, since the supply ofwater for both drinking and sanitation is limited.The frequency of drought events suggests thatthere may be a case for establishing a droughtresponse budget line.The likelihood that a hazardous event will///have a significant impact on the MarshallIslands has risen with the increasing levelsof population and assets in the urban areasof Majuro and Ebeye. These low-lying atolls are///at risk of damage to both assets and people as aresult of storm surges and tsunamis. In December2008, a state of emergency was declared followingweeks of high seas, which resulted from stormsurges coinciding with high tides and two tropicaldepressions (Marshall Islands Government 2009;UNOCHA 2008). These events caused damage toroads, houses, and other infrastructure on the lowlying atolls of Majuro and Ebeye. Similar events areexpected to become more frequent with climateSource: PCRAFI 2011.Section02

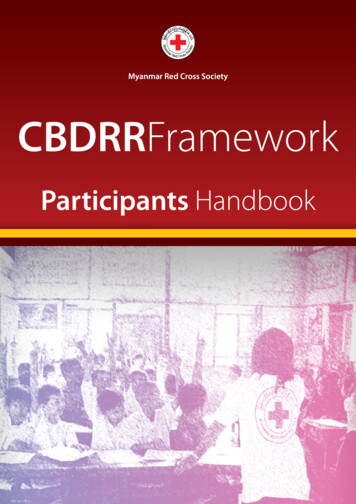

PCRAFI08MARSHALL ISLANDSFigure 3 — Direct Losses by Return PeriodDIRECT LOSSES (MILLION USD)300250TC EQ200EQTC15010050Source: PCRAFI 201100100200300400500600700800900Note: TC tropical cyclone; EQ earthquake.1000MEAN RETURN PERIOD (YEARS)change and rising sea levels. Figure 2 shows the0 0.25 0.5economies are highly dependent on10 NThe remote atoll and island subsistence///18 Naccrued over time.Kilometersagriculture, which in turn is highly susceptibleKwajalein Atollto adverse weather conditions. An estimated0///6,384 people were affected by the drought in150 300600MajuroAtollKilometers2013 (RMI 2013b). Household water catchments162 E 164 E 166 E 168 E 170 E 172 Eand other water storage facilities ran out of water,Ebeyeand levels of salinity in underground water sourcesKwajaleinAtollbreached safety levels for consumption. Theprolonged drought and high groundwater salinityLauralevels devastated food crops such as breadfruit,0banana, and taro. This situation will have long-12Kilometerslasting impacts on food security and the health ofKwajalein 00.51Total Average AnnualLoss (thousand USD)0 - 1010 - 1515 - 3030 - 5050 - 7575 - 1006501830the populations of the affected atolls.The Marshall Islands is vulnerable to losses///0from tropical cyclones, which cause damageto buildings, infrastructure, and livelihoods. In00.2510.51Kilometers23///1997, for example, Typhoon Paka caused US 80million of damage to crops and affected 70 percentSection02KilometersDelapof houses on Ailinglaplap Atoll (PCRAFI 2011).During a 20-year period, cyclones in the MarshallIslands caused on average US 63 million per6 NMarshallIslandsprovides an indication of the assets that have12 NFigure 4 — Average Annual Losses by Arealocation of buildings in the Marshall Islands andLaura8KilometersMajuro AtollSource: PCRAFI 20110 2 4Delap

PCRAFIMARSHALL ISLANDS09cyclone (SPC-SOPAC 2012); Typhoons Zelda, Axel,and Gay caused significant damage and loss withinthe span of one year (1991–1992).The Marshall Islands is expected to incur,///on average, US 3 million per year in lossesdue to earthquakes and tropical cyclones. In///the next 50 years, it has a 50 percent chance ofexperiencing a per-event loss exceeding US 53million, and a 10 percent chance of experiencing aper-event loss exceeding US 160 million (see figure3).The expected average annual loss can also beshown by area, as in figure 4. Areas colored inred indicate high levels of average annual losses,ranging from US 0.78 million to US 2.1 million.The full risk profile for the Marshall Islands can befound in annex 3.Photo Credit//////Stefan Lins/Flickr b

PCRAFI10MARSHALL ISLANDSPublic FinancialManagement ofNatural DisastersIn the Marshall Islands, a major constraint///The CFA agreement was amended in 2004 to///in financial response to natural disasters isinclude specific guidance on establishing thethe limited number of staff to implementDisaster Assistance Emergency Fund (DAEF)—activities. Authority lies with a few key individualsdiscussed below—and accessing additional post-who are also responsible for many other portfoliosdisaster financial support from the U.S. Agency for//////of work. The drought response occurred at analready busy time—that is, when the Ministry ofFinance was preparing for the annual regionalForum Leaders Meeting and working on the 2014budget and annual donor round table.The Compact of Free Association (CFA)International Development (USAID). According tothe amended CFA, additional finance is availableonce one of the following criteria is met: “(i) thePresident of the Republic of the Marshall Islandsofficially declares a national state of emergencyin accordance with the laws of the Governmentof the Republic of the Marshall Islands; (ii) the///agreement, established with the United Statesin 1986, provides the Marshall Islands witheconomic assistance worth around US 45million a year until the agreement expires in2023. In 2013 the CFA agreement provided over///disaster is deemed to be beyond the ability ofthe Government of the Republic of the MarshallIslands to respond, including taking into accountthe available resources of the Disaster AssistanceEmergency Fund and the need to protect thesustainability of the Fund; or (iii) the GovernmentUS 72 million in funds in total. But use of theof the Republic of the Marshall Islands hasfunds must be related to the specific areas detailedrequested assistance through the United Nationsin the agreement, which states that “fundsdesignated representative for the coordination ofreceived under the CFA, as amended shall not bedisaster and humanitarian assistance.” (CFA 2004).transferred to any other activity, or reprogrammedor expended for any other purpose during thefinancial year” (Marshall Islands Government2013a).4In 2004, the renewal of the CFA agreement///provided a stream of grants, due to declineover time, that were aimed primarily at

PCRAFIMARSHALL ISLANDS11Post-DisasterBudget Mobilizationthe education, health, and infrastructuresectors. When the annual grants under theCFA agreement cease in 2023, the MarshallIslands’ fiscal stress is likely to increase, as isits financial vulnerability to natural disasters.///The Marshall Island already faces many challengesassociated with gaining economic and fiscal selfsufficiency, and these are made greater by theoccurrence of natural disasters.The Ministry of Finance plays a leading role///in facilitating disaster response efforts. The///ministry waives normal tendering procedures uponreceipt of the statement of emergency, and itexecutes payments rapidly, sometimes on the sameday. Following the declaration of disaster in MayEffective post-disaster financial response relies on2013, the Ministry of Finance led a national post-two fundamental capabilities:disaster assessment of the ongoing drought in the(a) The ability to rapidly mobilize funds postdisaster; andnorthern islands, and it led a flash-funds appeal togenerate and consolidate donations from membersof the public and local businesses.(b) The ability to execute funds in a timely,The government takes an ex-ante approach///transparent, and accountable fashion.to DRFI, but its available resources are limited.///The next section discusses the existing proceduresfor post-disaster budget mobilization and executionand where possible provides examples of their use.While the government has a contingency budgetand access to the DAEF, the immediate cashavailable through the former is US 200,000 andTable 1— Sources of Funds AvailableSHORT TERM(1-3 MONTHS)MEDIUM TERM(3-9 MONTHS)LONG TERM(OVER 9 MONTHS)Ex-post FinancingDonor Assistance (relief)Budget ReallocationDomestic CreditExternal CreditCapital Budget RealignmentDonor Assistance (reconstruction)Tax IncreaseTax Incentives (Flash Appeal)Ex-ante FinancingEmergency FundContingency BudgetContingent CreditSovereign (parametric) CatastropheRisk InsuranceSectionTraditional Disaster InsuranceSource: Government of Marshall Islands; World Bank.03

PCRAFI12MARSHALL ISLANDSBox 1— The Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance PilotThe Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance Pilot aims to providegovernment in the aftermath of a severe natural disaster that disrupts theimmediate budget support following a major tropical cyclone orprovision of government services. Countries can choose between threeearthquake/tsunami. The insurance is designed to cover emergencylayers of coverage—low, medium, and high—depending on the frequencylosses, which are estimated using both a modeled representation of theof events. The lower layer will cover events with a return period of 1 in 10event based on hazard parameters and a calculation of total modeledyears, that is, more frequent but less severe events. The medium layer willphysical damage. Unlike a conventional insurance scheme, where a payoutcover events with a 1-in-15-year return period, while the higher layer willwould be assessed against actual incurred costs, this scheme pays out oncover less frequent but more severe events, or those with a return periodthe results of a model. The advantage of this approach is that it results inof 1 in 20 years. However, countries may request that a more customizeda much faster payout. The payout would act as a form of budget supportoption be developed for them.//////and would go some way to cover the costs that would be incurred by thethrough the latter is US 100,000. Consequentlyin gray are for generic instruments that to datethe government relies heavily on donor support tohave not been used in the Marshall Islands.fund post-disaster expenditures.Ex-Ante Practices and ArrangementsEx-post financial measures such as post-///disaster budget reallocation take betweenThe uncertainty surrounding internationalone and two weeks to mobilize and requireassistance has increased pressure on countries tocabinet approval.Reprogramming of funds canestablish domestic sources of finance for post-be done only following the declaration of disaster,disaster relief. This includes the establishmentwhich is normally a few weeks after the statementof national reserves or the transfer of risk toof emergency. This means that the reprogrammingthe international insurance market. The ex-anteof funds between ministries can take up to sixpractices and arrangements that have been madeweeks, although ministers can reprogram up toby the Marshall Islands are described below.///5 percent of their budget between departmentsDisaster Assistance Emergency Fundwith relative ease. Interdepartment reprogrammingcan be done within one or two days following thedeclaration of disaster.The Marshall Islands has a variety of ex-ante///and ex-post financial tools, and the time ittakes to mobilize and execute these fundsvaries significantly. Building on the World Bank///disaster risk financing and insurance framework(see annex 1), table 1 shows the ex-ante andSectionex-post financial tools available, indicates thoseutilized by the Marshall Islands, and gives indicativetimings. The tools utilized by the Marshall Islands03are highlighted in blue. Those sections highlightedUnder the CFA agreement with the United///States government, the DAEF was legallyestablished in 2004. The fund, which may///be drawn on only to pay for assistance andrehabilitation after a disaster or emergency,was first implemented in 2005. Each year, uponreceipt of US 200,000 from the Marshall Islandsgovernment, the DAEF receives an equal amountin the form of a grant from the United States. Thefunds held within the DAEF can accrue interestuntil they are released post-disaster. The total

PCRAFIMARSHALL ISLANDSSovereign catastrophe risk insuranceamount in the fund as of June 2013 was just over 1.5 million.13The Marshall Islands’ participation in the///The amount of funding released followingPacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance Pilotan event was increased in 2013 as a meansprovides access to an injection of liquidity///of setting a precedent for other donor funds.within the first month of an eligible disaster.After the government declares a state of nationalThe pilot was launched on January 17, 2013, andemergency, it can withdraw an amount of upthe Marshall Islands opted for coverage againstto US 100,000 per event. This amount reflectstropical cyclones with the associated hazards ofrenegotiation in 2013: initially, the amount wasstorm surge, precipitation from tropical cylone,S 50,000, but it became apparent that otherand flooding caused by tropical cyclone (see tabledonors saw this amount as a precedent and2).///contributed the same amount. The same patternwas witnessed during the drought response inMarch 2013: after the government withdrewUS 100,000, other donors matched this amount///In the event that the Marshall Islands///experiences a tropical cyclone with anestimated emergency loss that exceeds thewith their initial contributions.selected attachment point, the country willContingency budgetits contingency budget. Events that generatebe eligible for a payout worth over five times///an emergency loss beneath the attachment point5The Marshall Islands holds a nominal///contingency budget for the payment ofunforeseen expenditures equivalent tomust be managed by optimizing the use otherfinancial tools.US 200,000 each year. The process for decidingExternal debt///to draw on these funds is not legislated but reflectsself-imposed restraint and prudence by the staffat the Ministry of Finance. The limited amount ofcash means it can be easily exhausted either by adisaster or another unforeseen event.The current stock of public debt is equivalent///to 55.9 percent of gross domestic product(IMF 2013). Of this, approximately 97 percentis external. An estimated 64 percent of theexternal debt is central government debtTable 2— Selected Insurance Coverage, 2014–2015 Pilot SeasonTROPICAL CYCLONEPolicy periodNovember 1, 2014–October 31, 2015Peril selectedTropical cycloneLayer of coverage selected1 in 15 yearsCoverage limit as a percentage of contingency budget 500 percentReporting agencyJoint Typhoon Warning CenterSectionSource: World Bank.03

PCRAFI14to the Asian Development Bank, with theMARSHALL ISLANDSBudget reallocationbalance being state-owned enterprise debtThe Marshall Islands, like many small islandguaranteed by the central government.///states, has limited sources of domesticThe Asian Development Bank debt is all onconcessional terms. It is therefore expected thatrevenue and limited budget flexibility. The//////the level of existing debt will remain manageablein the coming years, although an increase in bothprincipal repayments and interest is expected tolargest sources of domestic revenue are taxeson trade and consumption, closely followed byrevenue from taxes on income and profits, whichrespectively generated US 17.3 million andoccur from about 2017. The current debt-serviceratio is estimated to be equivalent to 10 percent ofthe export of goods and services, down from 16.5US 11.3 million in fiscal year 2012/13 (IMF 2013).Grants from the CFA and from developmentpercent in 2010 (IMF 2013).partners amounted to 59.2 million. This meansGiven the relatively low levels of debtapproximately 62 percent of the annual bu

///The Marshall Islands is expected to incur, on average over the long term, annual losses of US 3 million due to earthquakes and tropical cyclones. /// In the next 50 years, the Marshall Islands has a 50 percent chance of experiencing a loss exceeding US 53 million, and a 10 percent chance of experiencing a loss exceeding US 160 million