Transcription

JGIMREVIEWSMentorship of Underrepresented Physiciansand Trainees in Academic Medicine: a Systematic ReviewEliana Bonifacino, MD, MS1 , Eloho O. Ufomata, MD, MS1, Amy H. Farkas, MD, MS2,3,Rose Turner, MLIS4, and Jennifer A. Corbelli, MD, MS11Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; 2Division of General Internal Medicine,Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA; 3Milwaukee VA Medical Center, Milwaukee, WI, USA; 4Falk Library of the Health Sciences,University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.BACKGROUND: Though the USA is becoming increasingly diverse, the physician workforce contains a disproportionately low number of physicians from racial and ethnicgroups that are described as underrepresented in medicine (URiM). Mentorship has been proposed as one way toimprove the retention and experiences of URiM physicians and trainees. The objective of this systematic reviewwas to identify and describe mentoring programs forURiM physicians in academic medicine and to describeimportant themes from existing literature that can aid inthe development of URiM mentorship programs.METHODS: The authors searched PubMed, PsycINFO,ERIC, and Cochrane databases, and included originalpublications that described a US mentorship programinvolving academic medical doctors at the faculty or trainee level and were created for physicians who are URiM orprovided results stratified by race/ethnicity.RESULTS: Our search yielded 4,548 unique citations and31 publications met our inclusion criteria. Frequently citedobjectives of these programs were to improve research skills,to diversify representation in specific fields, and to recruitand retain URiM participants. Subjective outcomes wereprimarily participant satisfaction with the program and/orwork climate. The dyad model of mentoring was the mostcommon, though several novel models were also described.Program evaluations were primarily subjective and reportedhigh satisfaction, although some reported objective outcomes including publications, retention, and promotion. Allshowed satisfactory outcomes for the mentorship programs.DISCUSSION: This review describes a range of successfulmentoring programs for URiM physicians. Our recommendations based on our review include the importanceof institutional support for diversity, tailoring programs tolocal needs and resources, training mentors, and utilizingURiM and non-URiM mentors.KEY WORDS: mentorship; underrepresented in medicine.J Gen Intern Med 36(4):1023–34DOI: 10.1007/s11606-020-06478-7 Society of General Internal Medicine 2021Prior Presentations The abstract of this work was presented as an oralabstract at the national meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicinein Washington DC in May 2019 and was a finalist for the Milton W.Hamolsky Jr. Faculty Scientific Presentation Award.Received April 3, 2020Accepted December 15, 2020BACKGROUNDThe USA is becoming increasingly diverse with Black andHispanic Americans accounting for 12.6% and 16.3% of thepopulation, respectively.1 Although there have been numerousnational efforts to increase diversity in the physician workforce, numbers of medical school graduates from these ethnicand racial groups remain disproportionately low at 6.2% and5.3%, respectively.2 While the numbers of medical studentsfrom groups that are traditionally underrepresented in medicine (URiM) are increasing, this has not occurred for all ethnicand racial groups equally, as Black male applicants and matriculants to medical school have declined since 1978.3Many studies have underscored the vital importance ofdiversity in the medical workforce. Having physicians fromURiM backgrounds, which increases patient-physician concordance, has been associated with benefits for patient care,including increased satisfaction,4 perceived quality of care,5and adherence to medication regimens.6 Additionally, URiMphysicians are more likely to practice in medically underserved and low-income communities.7 In research, papers thatare coauthored by ethnically diverse contributors have greaterimpact on the scientific community as measured by publication in higher impact factor journals and number of citations8;moreover, diversity in research team members can yield greater improvements in problem-solving.9Despite the benefits associated with diversity in the medicalworkforce, significant disparities exist. Physicians from URiMbackgrounds remain underrepresented at all levels of academic medicine.10 URiM academic faculty are promoted at lowerrates,11 and both faculty and trainees report feelings of isolation and lower career satisfaction.12 Disparities also exist inscientific research with one study demonstrating that Blackscientists were 13% less likely to receive NIH funding whencompared to white scientists.13Mentorship is one proposed mechanism to address disparities for URiM physicians and trainees and has been associatedwith increased career satisfaction,14 research productivity, andpreparedness for junior faculty.15 Unfortunately, URiM physicians are less likely to have mentors both as trainees16 and asfaculty.17 Two prior reviews in 2013 and 2014 aimed toidentify programs created to address the importance ofPublished online February 2, 20211023

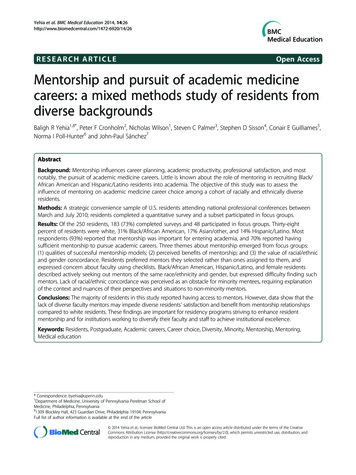

1024Bonifacio et al.: Mentorship of Underrepresented Physicians and Traineesmentorship and faculty development for URiM academicfaculty, but did not include trainees.18, 19 We aimed to conducta systematic review that identified and described existingmentoring programs for URiM physicians, inclusive oftrainees, to identify barriers and facilitators to the success ofsuch programs, and to assess for themes in mentorship programs for URiM physicians across the continuum of training.METHODSSearch Strategy and Study SelectionThis study was performed as part of a larger systematic reviewthat was reported upon in two prior publications.20, 21 Wesearched PubMed (1946–present), PsycINFO (1957–present),the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) (1966–present), and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(1992–present), following the Preferred Reporting Items forSystematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. Our search strategy was developed in collaboration witha health sciences librarian (RT). The search strategy wasdeveloped using a combination of database-specific subjectheadings and keywords for the concepts of mentorship andacademic medicine. Only those subspecialty terms that addedunique references were included in the final search (Appendix). We also examined previously published systematic reviews to assure completeness of our search. We finalized oursearch on September 11, 2019. Two authors (EB and EU)independently evaluated all records for eligibility usingDistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada), a webbased systematic review data management system. We resolved discrepancies by group discussion including the seniorauthor (JC).Study Eligibility CriteriaWe included original publications that (1) described a mentorship program as defined below; (2) involved (though notnecessarily exclusively) academic physicians or trainees(medical students, residents, fellows); (3) described a programdesigned for persons who are from URiM backgrounds, orprovided results stratified by race/ethnicity; (4) described a USprogram; and (5) were published in English. We registered ourdetailed protocol on PROSPERO (University of York, York,UK), which can be accessed at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display record.php?ID CRD42018067598.We accepted the definition of mentorship as proposed byBeech et al.: “a developmental partnership in which knowledge, experience, skills and information are shared [ ] tofoster the mentee’s professional development and [ ] alsoto enhance the mentor’s perspectives and knowledge.”18 Wedid not consider technique- or skill-teaching programs asmentorship programs. We utilized the Association of American Medical Colleges’ definition of the concept “underrepresented in medicine”: “those racial and ethnic populations thatJGIMare underrepresented in the medical profession relative to theirnumbers in the general population.”22 We limited our searchto the USA in order to maximize generalizability for USprograms, as racial/ethnic demographics, and therefore whichgroups are considered underrepresented, are society-specific.Data AbstractionTwo study authors (EB and EU) independently abstracted thedata, which included author and year published, number ofmentors and mentees, model of the mentorship program (e.g.,dyadic, peer mentoring), educational training level, racial/ethnic demographics, program objectives and components,method of evaluation and results, and barriers and facilitatorsof mentorship programs.Study QualityWe were unable to perform a quality or bias assessment on 24of the 31 included publications that presented descriptive dataonly, as no validated measures exist to assess quality of bias,and due to the heterogeneity of study design, outcome andassessment methods. One study23 was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and five presented data at two or more timepoints.24–28 For these, we applied the National Heart, Lungand Blood Institute (NHLBI) Quality Assessment Tools forControlled Intervention Studies and for Before-After Studieswith No Control Group, respectively.29 One study was qualitative,30 and we applied the Critical Appraisal Skills Program(CASP) Checklist for Qualitative Studies.31 Two authors (EBand JC) independently applied quality assessment tools toeach study. Overall quality ratings based on the scale wereassessed, and discrepancies were resolved through group discussion to reach consensus.Development of Key ThemesKey themes were developed through an iterative process. Twoauthors (EB and EU) independently generated a list of keythemes synthesized from careful review of all included papers.Criteria used were that themes should be both actionable andgeneralizable, and directly driven by results of included studies. Themes were discussed and refined, and where discrepancies existed, consensus was reached through deliberationand agreement with all study authors who were blinded towhether each theme was on one of both initial lists.RESULTSPublication SelectionWe retrieved a total of 4,548 citations. After screening forduplicate records, 4,207 remained. A total of 3,476 recordswere excluded based on title and abstract screening, and 731underwent full text review. In total, 31 publications23–28, 30, 32–55met all of our criteria and were included in the data analysis.

JGIMBonifacio et al.: Mentorship of Underrepresented Physicians and TraineesRecords identified throughPubMed, ERIC, PsycINFO, andCochrane Databases(n 4,548)Records remaining afterduplicates removed(n 4,207)1025Duplicates removed(n 341)Records excluded bytitle/abstract (n 3,476)Articles excluded:Full text articlesassessed for eligibility(n 731)1. Did not stratify results by URiM status(n 355)2. Did not describe a mentoring program(n 197)3. Not a US program/not in English (n 109)4. Does not involve physicians (n 39)Publications included(n 31)Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram of publications identified in systematic review. ERIC, Education Resources Information Center; URiM,underrepresented in medicine; US, United States; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.Reasons for exclusion of the remaining articles are enumeratedin Fig. 1. The 31 publications described 28 mentorshipprograms.QualityApplying NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools, four studies24, 26–28 were deemed to be of fair quality, and two studies23, 25 deemed to be of good quality. The CASP Checklist isnot designed to have a scoring system. Checklist results indicate that results of the qualitative study included30 are validand can be applied to local populations.Program ParticipantsThe majority of programs were targeted at specific academiclevels, with seven programs targeted specifically to medicalstudents,26, 28, 32, 34, 38, 52, 53, 55 two programs specifically forresidents,37, 48 10 programs specifically created for juniorfaculty,24, 25, 30, 40–46, 51, 56 two programs addressed MD/DOtrainees in post-doctoral programs,43, 44, 47 and one addressedall faculty members.33 Seven programs included more thanone academic or training level,23, 35, 36, 39, 49, 50, 54 rangingfrom high school students to faculty members. The number ofmentees in each program ranged from seven46 to more than200.23, 27, 32, 36, 51Half of the 28 programs were specifically created for URiMphysicians and trainees, 26–28, 30, 33, 34, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 44, 48, 52,54, 55whereas the remaining 14, though not specifically createdfor URiM mentees, provided results stratified byrace/ethnicity. Of those that included specific racial and ethnicdemographic information, 14 included Black mentees,24, 27, 28,30, 32, 35, 37, 39, 47, 50–5412 included Hispanic or Latinxmentees,24, 27, 28, 30, 32, 37, 39, 44, 47, 50, 51, 54 and five includedAmerican Indian/Alaska Native mentees.27, 37, 39, 43, 44, 50Eighteen programs did not specify the racial or ethnic demographics of the mentors in their program.23–28, 30, 32, 33, 36, 38,41–45, 47, 49–51, 54Three programs were led by URiM mentorsonly,34, 52, 53 while the rest included mentors from both URiMand non-URiM demographics in varying proportions(Table 1).Mentorship ,56 of the 28 programsexclusively used a traditional dyadic mentorship model, whichincludes a pair of a more experienced mentor and a juniormentee. The dyadic model of mentorship was used almostexclusively by those programs published prior to 2000,52, 53, 55whereas more varied models of mentorship emerged sincethen.Two programs33, 46 utilized a peer or horizontal mentorshipmodel, in which individuals of the same rank or experiencementor each other.46, 57 A group model of mentorship, whichincludes groups of multiple senior mentors and multiple juniormentees,58 was utilized in two programs.34, 39 Two programsinstituted a dyadic model in combination with a peer model ofmentorship.23, 51 One of these programs was a RCT of mentorship interventions in URiM graduate students, fellows andjunior faculty in health sciences that compared peermentoring, a dyadic model where mentors received specifictraining, the combination of the two, and usual practice.23 Inthree of the papers included in this review, the model ofmentorship was unspecified.30, 48, 54

1026JGIMBonifacio et al.: Mentorship of Underrepresented Physicians and TraineesTable 1 Description, Objectives, and Evaluation of Mentorship Programs for URiM Physicians and TraineesStudy n t surveyMentees: 197junior facultyMentors: SeniorfacultyMentees: 6.7%Black3.0% LatinoMentors:UnspecifiedPeer mentoringand postsurveyMentees: 204junior facultyMentors:UnspecifiedMentees: 67%Black, 27% Latino,4% AmericanIndian or re/postsurveyMentees: 15medicalstudentsMentors:UnspecifiedMentees: praisalInventory,Ragins andMacFarlinMentor RoleInstrumentSurvey,publication,and recruitmentIncrease in skills forsuccess for grantsHigh satisfactionscores100% of URiMgrant applicantsreceived grantsGreater number ofindependentinvestigator awardsreceived after training compared tomentored-researchawardsMentorshipimportant indeveloping researchproposals andcareer advancementFairLewis23(2016)RCTMentees: 150graduatestudents,fellows, orjunior facultyMentors: 150facultyMentees: 47%URiMMentors:UnspecifiedDyad and peerPre-post NeedSatisfactionScale andWork (survey,interviews,and focusgroups)Mentees: 29junior facultyMentors:UnspecifiedMentees: 79%Black17% dmethods(survey andinterviews)DescriptiveMentees: 13medicalstudentsMentors: 16mentors inlaboratoryscience, clinicalresearch,clinical practiceMentees: 54%Black, 46% LatinoMentors:UnspecifiedFunctional dyadSurvey andqualitative dataHigh studentsatisfaction withmentorship androtationAverage of 1.7publications, sixresulting fromdirect mentorshipSeven studentsapplied to ENTresidency, andincreased numberof URiM ENTresidents at homeinstitutionGreater satisfactionof needs withmentor at 2 monthsin mentor traininggroupNo difference at 12months insatisfaction amonggroupsNo difference atany time point insatisfaction at workNumber ofpublications rose intraining period5 mentees promotedGreater successwith NIH grantsthancontemporaneousapplicants (33% vs.17.4%)High ratings inperception ofmentor-mentee relationshipAll students werevery satisfied (92%)or satisfied (8%)with programAll mentorsenjoyed theirexperience, andexpected ontinued on next page)

JGIM1027Bonifacio et al.: Mentorship of Underrepresented Physicians and TraineesTable 1. (continued)Study 2015)Post surveyMentees: 191medicalstudentsMentors:UnspecifiedMentees: 17.3%Black; 9.9%HispanicMentors:UnspecifiedDyadSurvey andpublicationLin33 (2016)DescriptiveMentees:Unspecifiednumber offacultyMentors:Unspecifiednumber offacultyMentees: URiMMentors:UnspecifiedPeerNumber ofURiM faculty,academic rank,and salaryPachter37(2015)DescriptiveMentees: 65residentsMentors: 47fellows, 38senior mentorsMentees: 75%Black15% Latino2% NativeAmerican/AlaskanMentors: 66% offellows URiM,50% of seniormentors URiMDyadic (eachparticipant hasone juniormentor and onesenior mentor)% ofparticipants inacademiccareers entees: 37%Black, 30% Latino,2% rainingoutcomesde Dios35(2013)Post surveyMentees: 7healthprofessionalstudents, entees: 2interns, 7 postdoctoral fellows, 5 juniorfacultyMentors: 29facultyMentees: 21%Black, 7% biracial,14% AsianMentors: 7%biracial3% Latino10% Asian17% unknown62% CaucasianDyadSurveyAfghani36(2013)Post surveyMentees: 253high schoolstudents, 36undergraduatestudents, 12medicalstudentsMentors: 8–9facultyMentees: 22% ofhigh schoolstudents URiM67%undergraduatestudents URiM,92% medicalstudents URiMMentors:Unspecified“Cascading,” (5high schoolstudentsmatched withoneundergraduatestudent, 2-3 undergraduate students matchedwith 1 medicalstudent)SurveyHarris39(2012)Post survey13 medicalstudents, 28residents, 12junior faculty, 6community41% Black, 32%Asian, 11% Latino1% NativeAmerican, 15%Caucasian, 1%GroupAcademicproductivityEvaluation resultsrelationship withscholarIncrease in allknowledgedomains, and manyskill-related domains50% of URiMparticipants pursuedacademic positionsIncreased interest ingeriatricsParticipantscoauthored 582manuscripts, 11NIH grants, 3 Kawards, 4 RO1sIncreased URiMfaculty from 2 to 4Increased URiMfull professors from0 to 1Salary equal byrank andsubspecialtytraining63% of participantsare in academiccareersParticipants reportpositive commentsabout networkingand friendship,exposure toresearch, and careerdirectionOf 36 participants,28 have jobs inhealth-related fields,or have been accepted to graduate/medical schoolsAll menteesreported being verysatisfied (54.5%) orsatisfied (45.5%)with theirexperienceMajority (90.9%)planned to continuerelationship withmentorMedical studentsreportedimprovement inself-confidence,motivation forcareer in academicmedicine,leadership abilities,teaching skills andcare forunderservedpopulationsMedical students,residents, and juniorfaculty have allreportedpublications, /AN/A(continued on next page)

1028JGIMBonifacio et al.: Mentorship of Underrepresented Physicians and TraineesTable 1. (continued)Study ographicsmembers, 16senior faculty, gramevaluationEvaluation resultspresentation, andnational and localawards directly as aresult of thisprogram100% completedprogramProgram yielded 42peer-reviewed manuscripts and 16funded grants81% of participantspursuing career inNeuroAIDSresearchOf participants nowin practice, 57%hold positions asfull-time facultymembers4 mentorship pairswere successful60% increase inpromotion forURiM faculty,though no changein percent of URIMfaculty at any rank5 URIMfaculty/fellowsawarded fellowships89% of respondentsrated program asvaluableRespondents valuedmeeting otherstudents (43%) andmentors (54%)Respondents ratedprogram as relevantto professional(84%) and personal(88%) development24/31 funded grantproposals within 2years4/11 promoted toassociate escriptiveMentees: 88menteesincluding 40MD/PhD candidates and 26 junior facultyMentors:FacultyMentees: Mostfrom ademicproductivity,recruitmentButler48(2010)Post surveyMentees: URiMMentors: URiMand non-URiMUnspecifiedNumber ofgraduates inacademiccareersEmans42(2008)Post surveywith followupMentees: 76general surgeryresidentsMentors:FacultyMentees: e34(2008)Post surveyMentees 34medicalstudentsMentors: 17facultyMentees: URiMMentors: ptiveDescriptiveMentees: Hispanicand ionsLewellenWilliams40(2006)DescriptiveMentees: URiMMentors:Unspecified forpeer, distance.Onsite facultyURiMPOD (PeerOnsite-Distance)which includesDyad (includingdistance), entees: 19PhD, MD, andMastersstudentsMentors:FacultyMentees: 22junior facultyMentors: 9peers (juniorfaculty), 10onsite faculty,unspecifieddistance (privatepractice,governmentfigures)Mentees: JuniorfacultyMentors: SeniorfacultyMentees: URiMMentors:UnspecifiedDyadRetention, andpromotionIncreased 5-year retention rate (58%)compared to beforeprogram (20%)Increase in numberof URIM faculty(7.5%) compared tobefore program(6.9%)Proportion of tenuretrack increasedN/AN/AN/AN/AN/AN/AN/A(continued on next page)

JGIM1029Bonifacio et al.: Mentorship of Underrepresented Physicians and TraineesTable 1. (continued)Study (2004)Pre-postsurveyMentees: 67junior facultyMentors: 59senior facultyMentees: on)Mentees:114junior facultyMentors: SeniorfacultyMentees: nes47(2006)DescriptiveMentees: 7junior facultyPeer mentoringNoneDescriptiveMentees: 15medicaldoctorates orPhDsMentors: SeniorfacultyMentees: DiverseculturalbackgroundsMentees: 20%Black, 13% Latino,7% AsianMentors:UnspecifiedMosaic:research dinterviews,focusgroups)Mentees:Preceptorship:20 juniorfacultyMentorship: 9junior facultyMentors: 29senior facultyMentees:Preceptorship:15% Asian, 9%Black, 3% LatinoMentorship: 22%Asian, 6% Black,6% ethy55(1999)Post surveyMentees: 30medicalstudentsMentors: 15FacultyMentees: surveyMentees:Medicalstudents,Mentees: AfricanAmerican etentionRetentionEvaluation results(44%) compared tobefore program(25%)Participants weremore confident inacademic roles,skills in research,education, andadministrativeresponsibilities5/6 URiM facultystayed at institution,6/6 stayed in academic medicineFour-year retentionrate of URiM juniorfaculty at institutionincreased from 58to 80%Increase in retentionrates in academicmedicine from 75to 90%None5/9 graduatedparticipants are inresearch-based academic careers2 MDs leftacademia due tounsupportiveclimate for womenand low salaryHigher participationfrom Asian, Black,and Latino facultyPsychosocialfunctions (e.g.,counseling,friendship, rolemodeling) ratedhigher than careerfunctionsPreceptorshipvalued highly bymentors (89%) andmentees (83%).Mentorship valuedby mentees (60%)and mentors (75%)Minority facultyretained at 100% inprecepting program,while 33% infaculty withoutpreceptorsHigh rating ofsatisfaction in bothmentees (5.1 out of7) and mentors (6.4out of 7)Mentees met withmentors an averageof 3 in 1 yearValued groupmeetingsPercent of URiMstudents obtaininghonors airN/AN/A(continued on next page)

1030JGIMBonifacio et al.: Mentorship of Underrepresented Physicians and TraineesTable 1. (continued)Study edtrainees, facultyMentors:FacultyMentors:UnspecifiedMentees: 37medicalstudentsMentors: 13facultyMentees: 43medicalstudentsMentors: 26faculty orcommunityphysiciansMentees: BlackMentors: BlackDyadUnspecifiedMentees: BlackMentors: BlackDyadUnspecifiedEvaluation resultswith 3 of therequired clerkshipsOutcomes forfaculty andadvanced traineesnot availableStudents valuedtheir mentorsStudents valuedacademic support,insight into clinicalrotations andprivate practice,role modelprofessional andpersonal balance,and enhancemedical RiM, underrepresented in medicine; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; RCT, randomized controlled trial; NIH, National Institutes of Health; K awards, NIHCareer Development Awards; RO1s, NIH Research Project Grants; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MD, Doctor of Medicine; PhD, Doctor ofPhilosophy; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndromeaQuality assessments were performed for those publications with study designs for which a validated quality assessment scale existsbNational Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Quality Assessment Tools for Controlled Intervention Studies and for Before-After Studies with NoControl Group quality scores reached by consensus of two authors after applying scalecCASP checklist results indicate that results of the qualitative study included are valid and can be applied to local populationsSeveral novel models of mentorship were described bypublications in this review. One program described a PeerOnsite-Distance model which featured peer mentors who wereclose to the mentee in rank; senior faculty as on-site mentors toserve as advocates, liaisons, or coaches; and distance mentorswho are leaders in healthcare, business, academia, or politicalsettings.40 Another approach featured a cascading mentorshipmodel in which eight or nine senior faculty members wereeach paired with multiple medical students, who in turn,mentored two or three undergraduate university students,who then mentored a group of five high school students.36The mosaic model, which was aimed to increase the sex andracial/ethnic diversity of researchers in aging, described aresearch program that featured individual research mentoring,career coaching, and counseling from the program director andother senior female faculty members.47 The last model utilizeda “community of mentors” scheme, which was operationalizedthrough a three-tier system that gave faculty basic logisticalinformation, and skills appropriate to their developmentalneeds, and conducted institutional initiatives to enable committed professional relationships.42Program Objectives and ComponentsNine of the 28 programs described in our study sought toimprove research skills of mentees.26–28, 30, 32, 38, 43, 44, 46, 49,50, 54Ten of the 28 programs were intended to increase representation in a specific content area.26, 28, 30, 32, 33, 37–39, 47–49 Fiveprograms designated recruitment and retention of URiM menteesas one of their primary program objectives.25, 39, 40, 42, 45, 54 Forsix programs, their goal was to provide support to menteesthrough their mentorship programs34, 35, 41, 42, 53, 55Two publications aimed to further mentorship research:one described a new mentorship model that could beadapted to other insitutions,40 and the other was an RCTthat evaluated whether mentorship models satisfied psychological needs.23 Other program objectives were to develop leadership skills and opportunities,36, 42 teachingskills,36, 46 clinical skills,36, 48 and cultural competence;52train mentors,55 enhance socialization,52 and networking;24, 48 and to orient junior faculty to the division.24Evaluation Methods and ResultsFourteen programs utilized a survey-based assessment.23–28,30, 32, 34–36, 38, 42, 51, 55The seven programs that assessedreported satisfaction and perception of the value of the program found high satisfaction and value ratings24, 26, 28, 34, 35,51, 55The previously mentioned RCT comparing mentor training, peer mentoring, combined peer mentoring and mentortraining, and usual mentorship found no difference in satisfaction at 12 months between groups; moreover, all groups hadhigh satisfaction ratings.23Ten programs assessed academic productivity includinggrants received and peer-reviewed publications.26, 27, 30, 32,

JGIMBonifacio et al.: Mentorship of Underrepresented Physicians and Trainees39, 42–44, 47, 49, 51Though these papers list the number ofmanuscripts and grants, no comparison group is available.Three programs addressed recruitment.26, 33, 41 Onefound that their program was associated with increasednumber of residents of URiM backgrounds in their otorhinolaryngology program compar

abstract at the national meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in Washington DC in May 2019 and was a finalist for the Milton W. Hamolsky Jr. Faculty Scientific Presentation Award. Received April 3, 2020 Accepted December 15, 2020 J Gen Intern Med36(4):1023-34 Published onlineFebruary 2, 2021 JGIM REVIEWS 1023