Transcription

E x t e n s i o n B u l l e t i n 2 7 1 9 , N e w, O c t o b e r 2 0 0 0Natural Enemies in Your Garden:A Homeowner’s Guideto Biological ControlMICHIGAN STATEU N I V E R S I T YEXTENSION

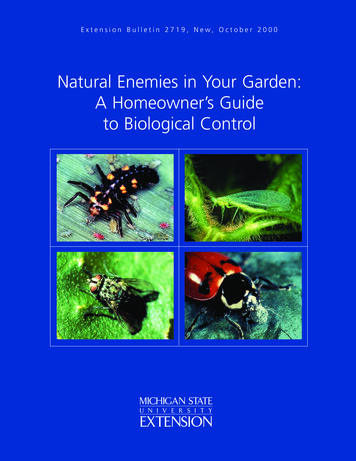

Cover PhotosFront cover, clockwise from top left Ladybug larva, Coccinella septempunctata (USDA). Green lacewing adult (Karim Maredia). Ladybug, Hippodammia parenthesis1. Tachinid fly adult (Dave Smitley).Back cover, from top Tomato hornworm covered with braconid parasitoid cocoons1. Carabid beetle adult, Calosoma spp. (Dave Smitley). Virus infected cabbage looper1.Text Illustrations Pages 21 ‘Orius’, 23, 25, 26, 28, 29, 32, 33, 35, 38, 44-46, and 48(Michelle Schwengel, Midwest Biological Control News). Pages 15-20, 21 ‘true bug’, 24, 33, 36, 40, and 42 (Jana Lee). Page 29 ‘Multicolored Asian lady beetle’ (William F. Lyon, O.S.U. Extensionfactsheet HYG-215-94: Multicolored Asian lady beetle). Page 37 (J.J. Culver, 1919, USDA Bulletin 766, plate 1). Page 47 (P. Berry, 1938, USDA Circular 485). Pages 34, 411.1(Michael P. Hoffman and Anne C. Frodsham, 1993,“Natural Enemies of Vegetable Insect Pests”, Cornell University).

Natural Enemies in Your Garden:A Homeowner’s Guideto Biological ControlJana C. LeeDouglas A. LandisDepartment of EntomologyMichigan State UniversityThis publication is a product of the Michigan State University Biological ControlProgram within the Center for Integrated Plant Systems. Funding was providedby the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station, Project GREEEN andMichigan State University Extension.MICHIGAN STATEU N I V E R S I T YEXTENSIONMICHIGANAGRICULTURALEXPERIMENTSTATION

Table ofContentsIntroductionWho are Our Friends in the Garden?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Making Biological Control Work for Us . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Conserving Natural EnemiesConservation Step 1: Don't Reach for the Pesticide Spray . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Conservation Step 2: Make a Home for Natural Enemies(Habitat Manipulation) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Augmenting Natural EnemiesNatural Enemies for Hire . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11What to Consider When Ordering Natural Enemies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Making Augmentation Successful . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Discovering Natural Enemies in Your Backyard —How to Sample . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14Natural Enemies of Common Pests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15PredatorsMinute Pirate Bugs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Stink Bugs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Assassin Bugs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24Damsel Bugs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24Bigeyed Bugs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25Green Lacewings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Ladybugs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27Rove Beetles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Ground Beetles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32Hover Flies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34Robber Flies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35Spiders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36ParasitoidsTachinid Flies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37Trichogramma Wasps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40Aphidius Wasps . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 422

Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t sCotesia glomerata. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43Cotesia melanoscelus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44Pteromalus puparum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45Diadegma insulare . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45Tiphia vernalis and T. popilliavora . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46Elm Leaf Beetle Parasitoids . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47Ooencyrtus kuvanae . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48PathogensNematodes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50Beauveria bassiana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52Entomophaga maimaiga. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54Bacillus thuringiensis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55Trichoderma harzianum, Strain T-22 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59Gliocladium virens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60AcknowledgementsThis book summarizes information from the Midwest Biological Control News that is ofinterest to homeowners and gardeners. The newsletter source and contributing authors aregiven at the end of each section. If you are interested in learning more about a particulartopic, you many find the original article and other articles of interest to you in thenewsletter online index at http://www.entomology.wisc.edu/mbcn/mbcn.html We thank the following people for their help and comments: Chris DiFonzo, DeborahMcCullough, Susan Mahr, Dean Krauskopf, Ralph Heiden, Angela Eichorn, Jerry Draheimand Jeanne Himmelein. We also thank Susan Mahr from Midwest Biological Control News,Michael Hoffman, Dave Smitley and Karim Maredia for use of their illustrations andphotos. Many illustrations from Midwest Biological Control News were drawn byMichelle Schwengel.3

IntroductionThe home landscape is a complexhabitat possibly consisting ofvegetables, flowers, turf, woodyornamentals and other desired, and in somecases, undesired plants. For most of us, ourgarden is a relaxing place where we tailor theenvironment to our aesthetic and physicalneeds. Yet the garden is also home tocreatures we consider pests when we findthem in our broccoli or apples or on ourprized rose bushes. As a result, the homelandscape has become the repository ofnearly 11 percent of the conventionalpesticides used in this country. Indeed, acrefor acre, your cousin Vinny's tomato patchhas more pesticides than farmer Joe'ssoybean field! Fortunately, the garden is alsohome to our friends, the natural enemies ofpests.Most gardeners learn a great deal about theirplants' growth needs, but they often knowlittle about the insects in their gardens. Mostof the insects in a garden are not harmfulpests. The vast majority of insect species inNorth America are either beneficial orharmless to humans and garden plants.To take advantage of the work that naturalenemies do (kill pests), we must first knowwhich ones we have and help them flourish.Using natural enemies to control pestsreduces your need to use pesticides and letsyou take a bite from cousin Vinny's tomatoes,right off the vine!— MBCN, v.4, n.4, Bryan Schmeiser and BobO'Neil, Purdue University.4Who are Our Friendsin the Garden?Most of us are familiar with spiders,ladybugs and praying mantids and knowthey eat a lot of bad bugs. Luckily, manyother natural enemies are also taking care ofpests. There are three major groups ofnatural enemies: predators, parasitoids andpathogens.Predators, such asladybugs and spiders,eat many prey in alifetime. Often they arelarger and stronger thantheir prey and the mostvisible natural enemiesin our garden. Some areC. maculataquick running hunters,while others sit and wait for a victim topounce on.Parasitoids arespecialized insectsthat develop asyoung in one host,eventually killingit. Unlikepredators, theyusually kill onlyone prey duringWasp on an eggtheir immaturestage. Many fliesand wasps are parasitoids, but they areusually small and therefore go unnoticed.

IntroductionPathogens— nematodes,viruses,bacteria, fungiandprotozoans —cause diseases.nematodeMany of thesenaturally occurin our gardens; others need to beintroduced. Commercial companies havebegun to develop many of these pathogensas bait or spray formulations, making themeasier for us to use.Making BiologicalControl Work for UsBiological control uses natural enemies tokeep unwanted pests at low levels.To practice biological control in the yard, youshould know the three basic approaches.Classical biological control is usedwhen pests are exotic in origin and exoticnatural enemies are imported and releasedto bring about control. This is conducted byfederal and state agencies. Although wehomeowners will not be importing naturalenemies into our backyards, some of thenatural enemies described in this book werebrought from other countries andestablished here. The importation of parasiticwasps to control alfalfa weevil in theMidwest has been a widely successfulclassical biological control program.Conservation biological controlencourages existing natural enemypopulations to flourish in the area andsuppress pests. This involves reducingpractices that harm natural enemies as wellas implementing practices that improvenatural enemy longevity, reproductive rateand effectiveness.Augmentation biological controlis the release of natural enemies into theenvironment in high numbers. This is donewhen natural enemies do not thrive well inthe environment or are not active during thetime of pest activity. Conservation andaugmentation of natural enemies are thehome gardener's tools to subdue pests, solet's get started!5

ConservingNatural Enemiesword of caution: not all traps are effective(see section on electric traps).Conservation Step 1:Don't Reach for thePesticide SprayTo conserve natural enemies in the homelandscape, first and foremost, we need toreduce insecticide use. The chemicals wespray to get caterpillars off broccoli also killor reduce the livelihood of natural enemies.Natural enemies take longer to re-establishthemselves than pests do. Using pesticidesmay also create new pests because it killsnatural enemies that are suppressing minorpests without our knowledge. When thenatural enemies are killed by a pesticide,these minor pests can become majorproblems.Kinder OptionsHome gardeners have many insect pestmanagement options other than insecticides.Adopting these options with attention to thelife cycles of pest and beneficial insects is akey component of integrated pestmanagement (IPM). Some IPM practicesinclude preplant cultural operations, such asselecting insect-resistant varieties, croprotations and companion plantings. After thegarden has been planted, harmful insectscan be managed in a variety of ways.6 When all other measures have failed, veryselective and well timed spot treatments ofindividual plant parts with a low-impactinsecticide (such as insecticidal soaps orhorticultural oils, which are relatively safecompounds for beneficials) may beconsidered. Tolerating a modest level of insect feedingon your garden vegetables will reduce theneed for chemical inputs. If cabbagewormseat part of your cabbage head, you canalways cut off the nibbled part and use therest.— MBCN, v.2, n.4, John Obrycki, Iowa StateUniversity, and Susan Mahr, University ofWisconsin - Madison.Conservation Step 2:Making a Home forNatural Enemies(Habitat Manipulation) If the garden is relatively small and insectpests are few, hand picking remains one ofthe most effective means of insect controlfor a gardener.Natural enemies require more than just food(pests to eat) to complete their life cycles.Predators and parasitoids may need anoverwintering site, protection from heat anddesiccation, plant food sources and earlyseason prey to sustain them if pests are notpresent. Managing the garden habitat tomeet the needs of predators and parasitoidsis an excellent way to conserve these gardenfriends and minimize the harmful effects ofcrop production on them. Traps or barriers can be useful for somepests, and biological control agents thatare commercially available can be veryeffective against specific insect pests. AOverwintering sites — Most pests aregenerally better at dispersal than their naturalenemies, so a garden may get colonized bypests long before natural enemies arrive. For

Conserving Natural Enemiesthis reason, it is all the more important thatoverwintering sites, such as floweringborders, hedges and other perennial habitatsbe provided for natural enemies. Thesevegetative sites insulate natural enemies fromthe winter chill. While some natural enemiesmay overwinter in the bare ground, we laterprepare the ground for planting and disrupttheir homes, sometimes killing them. Whenparts of the garden include undisturbedperennial plantings, natural enemies are morelikely to survive the winter.Mulches — Using mulches can reduce weedgrowth while providing humid, shelteredhiding places for nocturnal predators such asspiders and ground beetles. Also, the mulchmay make it harder for flying insects such asaphids and leafhoppers to see the crop byreducing the visual contrast between thefoliage and the soil surface.Flowers — Having certain flowering plantsavailable can greatly increase the longevityand fertility of many natural enemies. Astudy in Canadian apple orchards showedthat parasitism of orchard pests was four to18 times higher in orchards with manywildflowers than in orchards with fewflowers. A number of plant species havebeen shown to encourage natural enemies(see Table 2). Ladybug and lacewing adultsoften feed on pollen. Many natural enemiesthat benefit from floral nectar are smallElectric Traps Get Good Insects But Miss MosquitoesHave you or someone you know bought anelectric insect trap to keep the mosquitoesand other biting flies at bay? The snap,crackle and pop of fried arthropods mayseem to confirm their effectiveness, but arethese traps really doing much good? Thetraps in question use ultraviolet light to lurein flying insects, but many species ofmosquitoes are not attracted to light, andmany other non-target insects are attractedto lights and are inadvertently destroyed.Researchers in Delaware tracked the insectscaught in the electric traps of six homesnear lowland, wooded sites rich in aquaticbreeding habitats and, therefore, close tolots of mosquitoes and no-see-ums. Thesetraps were good at catching insects, theyfound 13,789 insects, but only 31 werebiting flies (a mere 0.22 percent). Nearlyhalf of the insects collected were nonbiting aquatic insects such as caddisfliesand midges. More importantly, the trapsdestroyed 1,868 insects from 27 families ofpredators and nine families of parasitoids.Ground beetles, rove beetles and braconidwasps were particularly common victims.Predators and parasitoids accounted for13.5 percent of the trap catch.By their calculations, the traps needlesslydestroy 71 billion to 350 billion non-targetinsects in the United States each yearwithout achieving any effective control ofnuisance insects. The heavy toll onbeneficial insects suggests that electrifiedtraps may actually be counterproductive forinsect control.— MBCN, v.3, n.10; T.B. Frick and D.W.Tallamy, 1996, Density and diversity ofnon-target insects killed by suburbanelectric insect traps, Entomology News,107(2): 77-82.7

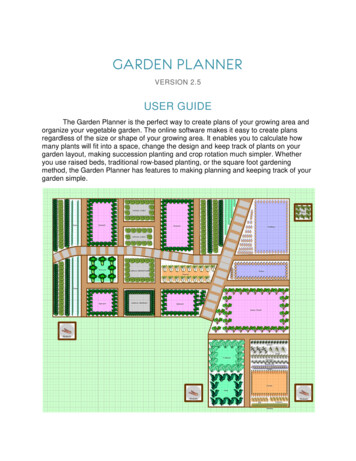

Conserving Natural EnemiesMaximizing Biological Control with Selective InsecticidesBiological control can be used as part of anintegrated pest management program tomaintain the appearance, health andstructural integrity of your valued plantings.The following guidelines will help youmaximize the potential for biological control: Monitor your plants regularly to recordplant health, pest and natural enemyabundance, and habitat disturbance. Use your records and experience todevelop situation-specific action thresholds and particular control strategies.parasitic wasps, often smaller than amosquito. Consequently, flowers that aregood for them are usually small, not overlytubular and relatively open. In addition,flowers ought to synchronize with naturalenemy activity. Planting a mixture of plantsthat bloom for long periods and overlap intime will ensure that food sources areavailable when natural enemies are active.Mulch AroundPlantsUndisturbed Grassy sGarden showing types of habitat manipulation to benefit natural enemies.8 When managing pests that occur early inthe season, consider the impacts ofnatural enemies on late-season pests. When thresholds are exceeded, usepesticides most compatible with biologicalcontrol. Some chemicals can be usedwithout significantly affecting naturalenemies, but most of the commoninsecticides are broad-spectrum and haverelatively long residual activity. ConsultTable 1 for specific information.Perennial plants often have shorter bloomingperiods than annuals, so particular attentionshould be given to plant diversity andblooming times in perennial bordersdesigned for natural enemies. Sequentialplantings of dill, coriander and caraway canbe made to provide a continuous source ofvaluable flowers.Ground covers — Leguminous cover cropsimprove soil fertility and provide shelter,floral food sources and alternate prey for awide variety of natural enemies. In covercrops, non-pest prey may be present andsustain natural enemies if their favorite pesthas not invaded the area.It should be apparent that a single recipe forsuccess using habitat manipulation does notexist. Consider altering gardening practicessuch as planting times, selecting cultivarsand mixing crops together to thwart pestsand enhance natural enemy survival.— MBCN, v.3, n.4, Shawn Steffan and PaulWhitaker, University of Wisconsin Madison.

Conserving Natural EnemiesTable 1. Pesticide Use Compatibility with Biological inesLindanenot compatiblevery long residual, broad-spectrumOrganophosphatesOrthene (acephate)not compatiblebroad-spectrumDursban , Lorsban (chlorpyrifos)not compatiblelong residual, broad-spectrumSpectracide (diazinon)not compatiblelong residual, broad-spectrumCygon (dimethoate)not compatiblelong residual, broad-spectrumCarbamatesSevin (carbaryl)not compatiblebroad-spectrum; repeated use maystimulate spider mite reproductionPyrethroidsAmbush , Pounce (permethrin)not compatiblelong residual, broad-spectrumBotanicalsPyrethrinsomewhat compatibleshort residual but very broadspectrumAzatin , Margosan-O (azadirachtin)compatibleinsect growth regulator derived fromseeds of neem tree; kills immaturestages; pupal stage parasitoids notaffectedInsect growthregulatorsDimilin (diflubenzuron)somewhat compatiblemoderate residual; kills immaturestages pupal stage parasitoids are notkilledMicrobial insecticides(pathogen biologicalcontrol agents)Bacillus thuringiensisvar. kurstaki Dipel ,Thuricide , Javelin (bacteria)highly compatibletargets caterpillarsBacillus thuringiensisvar. tenebrionis (bacteria)highly compatibletargets beetle grubsBeauveria bassiana(fungus)compatiblekills some soft-bodied predators;short residual, broad-spectrumSteinernema carpocapsaeBiosafe (nematode)highly compatiblevery low toxicity to humans and nontargets, wasp parasitoids with silkencocoons are not killedHorticultural oil(petroleum oil)compatibleinactive when dry; kills soft-bodiedinsects; pupal stage parasitoids notkilledSafer , M-Pede (insecticidal soap)compatibleinactive when dry; kills soft-bodiedinsects; pupal stage parasitoids notkilledOthers— MBCN, v.6, n.3, Cliff Sadof, Purdue University, and Michael Raupp, University of Maryland.9

Conserving Natural EnemiesTable 2. Good Flowers for Predators and Parasitoids.Umbelliferae (carrot family)caraway . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Carum carvicoriander (cilantro) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Coriandrum sativumdill . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Anethum graveolensfennel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Foeniculum vulgareflowering ammi or bishop’s flower . . . . . . . . Ammi majusQueen Anne’s lace (wild carrot) . . . . . . . . . . Daucus carotatoothpick ammi . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ammi visnagawild parsnip . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Pastinaca sativaCompositae (aster family)blanketflower . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Gaillardia spp.coneflower . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Echinacea spp.coreopsis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Coreopsis spp.cosmos . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Cosmos spp.goldenrod . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Solidago spp.sunflower . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Helianthus spp.tansy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Tanacetum vulgareyarrow . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Achillea spp.Legumesalfalfa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Medicago sativabig flower vetch. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Vicia spp.fava bean. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Vicia favahairy vetch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Vicia villosasweet clover. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Melilotus spp.Brassicaceae (mustard family)Basket-of-Gold alyssum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Aurinium saxatilishoary alyssum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Berteroa incanamustards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Brassica spp.sweet alyssum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Lobularia maritimayellow rocket . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Barbarea vulgariswild mustard . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Brassica kaberOther plant familiesbuckwheat. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Fagopyrum sagittatumcinquefoil. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Potentilla spp.milkweeds . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Asclepias spp.phacelia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Phacelia spp.10

If naturally occurring predators and parasitesare not sufficient to control garden pests,augmenting them with releases ofcommercially available natural enemies maybe effective. Insect pathogens are oftenproduced as formulations called microbialinsecticides for use in the yard. Not allnatural enemies are available because rearingthem may be difficult or costly.AugmentingNaturalEnemiesNatural Enemiesfor HireWhat is available? Green lacewings arecommonly sold and are a good option foraphid control. These predators can bepurchased and released early in the growingseason for earlier and more effective control.The eggs are shipped in small containersmixed with bran (or another filler, such asvermiculite) that protects the eggs duringshipping. All you have to do is sprinkle thecontents of the container on the plants.Other very popular natural enemies areTrichogramma wasps to controlcabbageworms, cabbage loopers, tomatohornworms and other caterpillars, andbeneficial nematodes to control a widevariety of garden pests. The most commonlyused microbial agent is a bacterium, Bacillusthuringiensis, or Bt. Microbial insecticides aresold by many chemical companies andcommon in stores. If you are interested inpurchasing predators or parasitoids, this is agood free source of information:— Suppliers of Beneficial Organisms in NorthAmerica by C. D. Hunter, from: CaliforniaEnvironmental Protection AgencyDepartment of Pesticide RegulationEnvironmental Monitoring and PestManagement P.O. Box 942871Sacramento, CA uppl.htmWhat to ConsiderWhen OrderingNatural EnemiesAsk the supplier for specific information andrecommendations for your particularsituation. Ordering and releasing naturalenemies can be successful if you: Know the specific pests you need tocontrol. Know the best natural enemies, eithersingly or in combination, for the targetpest or pests. Make sure companies11

Augmenting Natural Enemiesprovide the exact name of the naturalenemy that they are selling. Know the proper time to release thenatural enemy. Timing should be basedupon the life cycles of the pest and thenatural enemies. Know the proper release rate for eachnatural enemy. Calculate the number of natural enemiesneeded on the basis of release rate, area tobe covered and severity of pest infestation. Know the recommended frequency ofrelease if multiple releases are necessary. Provide a safe delivery address, one wherethe shipment will be cared for as soon asit arrives and where it will not be exposedto temperature extremes. Understand proper release practices so thatyou will be prepared to make releaseswhen the shipment arrives. Understand proper storage requirements ifreleases are not to be made immediatelyafter arrival.— MBCN, v.2, n.3.Making AugmentationSuccessfulReleasing loads of natural enemies in thegarden will take money from your pocket,but will it guarantee success? Sometimespredators and parasitoids will leave the areaor will not survive long enough to have animpact on pests. Maintaining a suitablehabitat, as discussed in conservationbiological control, is critical to improving thenatural enemy's efficacy. Be very judicious12What About Releasing Ladybugsand Praying Mantids?Ladybugs are good biocontrol agents, butwhat about the ones you buy? Chancesare these ladybugs are Hippodamiaconvergens. Many convergent ladybugsoverwinter in huge aggregations in theSierra Nevada mountains. This makes iteasy for suppliers to scoop them up, boxthem and sell them. Unfortunately, whenyou release these convergent ladybugs inyour backyard, they behave as they do inthe mountains — they fly away lookingfor the valley, their normal feedinggrounds. Some suppliers are nowpreconditioning ladybugs, letting them flyaround before you receive them so theladybugs will be less likely to fly away. Ifyou're interested in testing ladybugs inyour backyard, look for the activity box inthe ladybug section.What about praying mantids? Thoughthey certainly do prey on pests, mantidsare extreme generalists — they will eatvirtually anything they can catch, includingtheir siblings and other beneficials. Largemantids, such as the commerciallyavailable Chinese mantid, will even catchand eat bees and other pollinators. Adultmantids are very mobile, so they usuallywon't remain in the release site for long.Nevertheless, they are interesting. Becauseof their large size, big and seeminglyinquisitive eyes, and their “praying”stance, we seem to have an affinity forthem. If you wish to purchase them, do soas a source of education or interest, butdon't expect them to provide muchbenefit in pest management.- MBCN, v.2, n.4, Dan Mahr, University ofWisconsin - Madison.

Augmenting Natural Enemieswith insecticide use when releasing naturalenemies. Commercially reared insects willlikely find it just as hard to survive insecticideexposure as your normal yard insects. Also, adiversity of plantings (flowering plants,ground covers) will help maintain anadequate food supply and shelter so releasednatural enemies will remain in your gardendoing what you paid for them to do.Looking for the Silver BulletWe often look to biological control to worklike chemical controls. It would be nice ifone natural enemy was the silver bullet andtook care of the pest. Yet natural enemiesoften do not work that way. Releasing afantastic predator and having it becomeestablished in the system requires effort.We need to know what the predator needsand make sure alternative food sources andprotective shelter are provided. As you lookthrough this book, you will notice thatsome natural enemies eat a variety of pestsand others are very specific. Both areusually needed to obtain effective biologicalcontrol. Some specific natural enemies canbe very good at locating pests at lowdensities and keeping them low, whileother specifics may be good at bringingdown pest outbreaks. Generalists areimportant because they can feast on avariety of pests and are more flexible inwhere they can live. When a particularlybad pest arrives, the generalist naturalenemies are already in your garden ready todo their share of eating away the pestpopulation. Biological control of pests maytake many natural enemies and more efforton your part, but it can work in yourgarden!13

DiscoveringNatural Enemiesin Your Backyard —How to SampleYour garden contains a wealth of smallcritters. We tend to notice the bad orpretty ones, but there are plenty moreout there — we just need to keep an eyeopen for the

Using natural enemies to control pests reduces your need to use pesticides and lets you take a bite from cousin Vinny's tomatoes, right off the vine! — MBCN, v.4, n.4, Bryan Schmeiser and Bob . time of pest activity. Conservation and augmentation of natural enemies are the home gardener's tools to subdue pests, so let's get started .