Transcription

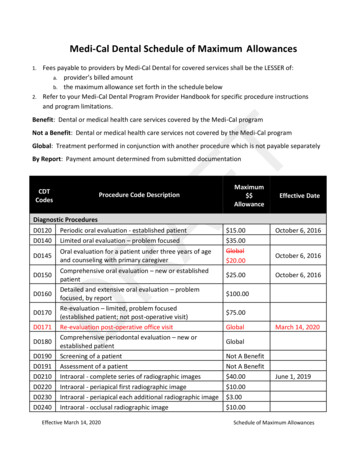

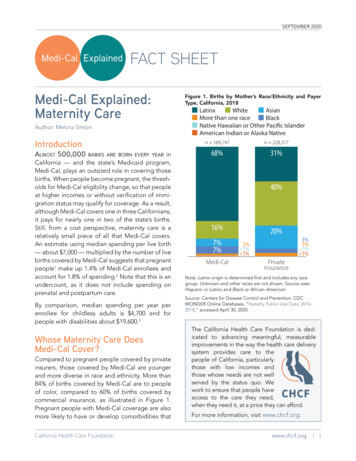

SEPTEMBER 2020Medi-Cal ExplainedNative Hawaiian or Other Pacific IslanderFACT SHEETAmerican Indian or Alaska NativeMedi-Cal Explained:Maternity CareAuthor: Melora SimonIntroductionLatinxAlmost 500,000WhiteinCaliforniaAsian— and the state’s Medicaid program,Medi-Cal,Blackplays an outsized role in covering thoseMorepeoplethan onerace pregnant, the threshbirths. WhenbecomeNativeHawaiianor change,Other PacificIslanderolds for Medi-Cal eligibilityso thatpeopleor AlaskaNative of immiat higherAmericanincomes Indianor withoutverificationgration status may qualify for coverage. As a result,although Medi-Cal covers one in three Californians,it pays for nearly one in two of the state’s births.Still, from a cost perspective, maternity care is arelatively small piece of all that Medi-Cal covers.An estimate using median spending per live birth— about 7,000 — multiplied by the number of livebirths covered by Medi-Cal suggests that pregnantpeople1 make up 1.4% of Medi-Cal enrollees andaccount for 1.8% of spending.2 Note that this is anundercount, as it does not include spending onprenatal and postpartum care.babies are born every yearFigure 1. Births by Mother’s Race/Ethnicity and PayerType, California, 2018LatinxWhiteAsianMore than one raceBlackNative Hawaiian or Other Pacific IslanderAmerican Indian or Alaska Nativen 189,747n 228,31768%31%19%By comparison, median spending per year perenrollee for childless adults is 4,700 and forpeople with disabilities about 19,600.3Whose Maternity Care DoesMedi-Cal Cover?Compared to pregnant people covered by privateinsurers, those covered by Medi-Cal are youngerand more diverse in race and ethnicity. More than84% of births covered by Medi-Cal are to peopleof color, compared to 60% of births covered bycommercial insurance, as illustrated in Figure 1.Pregnant people with Medi-Cal coverage are alsomore likely to have or develop comorbidities thatCalifornia Health Care Foundation40%16%7%7%Medi-Cal20%2% 1% 1%3%3% 1% 1%PrivateInsuranceNote: Latinx origin is determined first and includes any racegroup. Unknown and other races are not shown. Source usesHispanic or Latino and Black or African American.Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDCWONDER Online Databases, “Natality Public-Use Data, 20162018,” accessed April 30, 2020.The California Health Care Foundation is dedicated to advancing meaningful, measurableimprovements in the way the health care deliverysystem provides care to thepeople of California, particularlythose with low incomes andthose whose needs are not wellserved by the status quo. Wework to ensure that people haveaccess to the care they need,when they need it, at a price they can afford.For more information, visit www.chcf.org.www.chcf.org 1

SEPTEMBER 2020PrivatensuranceFigure 2.1 Maternal Characteristics by Payer Type,California, 2016–2018Pregnancy risk factors, %MedicaidPrivate InsuranceMedi-CalNon-Medi-CalAdvanced maternal agePrepregnancy elevated BMI15.9%49.0%30.7%62.6%Pregnancy risk factors29.5%27.7%Maternal tobacco use62.6%Preeclampsia6.1%5.8%Pregestational diabetes1.4%0.9%2.5%0.4%Prenatal depressive symptoms10.6%Figure 2.2 Maternal Characteristics by Payer Type,California, 2016–201820.4%Postpartum depressive symptoms14.2%10.2%Note: Pregnancy risk factors include prepregnancy and gestational diabetes and hypertension, eclampsia, previous pretermbirth, infertility treatment and/or fertility-enhancing drugs orassistive reproductive technology, and previous cesarean delivery.Gestational diabetes10.1%11.4%Asthma4.7%6.1%Source: The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative basedon 2018 Patient Discharge Data from the Office of StatewideHealth Planning and Development linked to Birth Certificate Datafrom the California Department of Public Health - Vital Records.Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDCWONDER Online Databases, “Natality Public-Use Data, 20162018,” accessed February 11, 2020. Depressive symptoms dataprovided upon request for 2016-17, Maternal and Infant HealthAssessment, California Department of Public Health, receivedJune 19, 2019.complicate pregnancy, such as elevated bodymass index (BMI), diabetes, preeclampsia, anddepression, as illustrated in Figures 2.1 and 2.2.How Are Maternity ServicesCovered in Medi-Cal?Like many other states, California has largelyembraced managed care, with more than 80% ofpeople covered by Medi-Cal now enrolled in amanaged care plan.4 However, 40% of births paidfor by Medi-Cal are still covered by the fee-for-service (FFS) system. The majority of FFS births are totwo groups of people newly eligible for Medi-Calon the basis of their pregnancy: (1) persons withoutverification of satisfactory immigration status andCalifornia Health Care Foundation(2) persons with incomes that are 139% to 213% ofthe federal poverty level (FPL), which in 2020 is anincome of 17,609 to 27,179 for a household ofone person.5In addition to being FFS, this special Medi-Calcoverage differs from standard Medi-Cal coveragein two ways. First, the coverage ends 60 days aftergiving birth, at which point people revert backto their prepregnancy eligibility status. This maymean they are no longer eligible for Medi-Calcoverage, though their baby will continue to becovered automatically through the first year of life.Second, for persons without verification of satisfactory immigration status, the coverage is limitedto pregnancy-related services6 and referred to aswww.chcf.org 2

SEPTEMBER 2020Table 1. Medi-Cal Eligibility and PregnancyImmigration StatusIncome LevelsCoverage TypeMedi-CalDelivery SystemPost-Pregnancy EligibilityCitizen or legalpermanent resident 139% of FPLFull-scope Medi-CalManaged careRemain eligible for full-scopeMedi-Cal managed careCitizen or legalpermanent resident139%–213% of FPL* Full-scope Medi-CalFee-for-serviceReturn to CoveredCalifornia; no longerMedi-Cal eligibleFee-for-serviceNo coverage except in caseof emergencyPerson without0%–213% of FPL*verification of satisfactoryimmigration statusRestricted scope —pregnancy-relatedMedi-Cal* For pregnant people with income levels that are 214%–322% of FPL, Medi-Cal can be accessed via buy-in to the Medi-Cal Access Program,which is administered by managed care plans. In 2020 for a household of one person, 139% of FPL is 17,609; 213% of FPL is 27,179; and322% of FPL is 41,087.“restricted scope.” Coverage details are describedin Table 1. The FFS system also covers those whoare found to be presumptively eligible by participating providers and are granted immediate,no-cost temporary coverage that continues for 60days while they apply for permanent Medi-Cal orother health coverage.7What Maternity Services DoesMedi-Cal Cover?All pregnant enrollees are eligible for medicallynecessary covered services, regardless of whethertheir care is administered by FFS or a managedcare plan.Examples of services covered: Obstetric care in an office, clinic, hospital outpatient setting, or alternative birthing center: Prenatal: Up to 13 visits across all primaryobstetrical providers per pregnancy in a ninemonth periodDelivery: Vaginal and c-section deliveryPostpartum care: One visit in a six-monthperiod unless the individual has a medical ormental health postpartum complication or isat risk for a postpartum complicationDiagnostic testing: Pregnancy determination,obstetric panel, depression screening, andgenetic testing as part of the California PrenatalScreening Program; ultrasounds provided outside of those for routine prenatal care (e.g.,nuchal translucency, advanced maternal age).California Health Care Foundation Specialty care and interventions (e.g., a glucometer for gestational diabetes, fetal wellbeing testing, prescription drugs, perinatalsubstance use disorder services) are coveredwhen medically necessary. Some interventions,such as a blood pressure monitor for home use,generally require prior authorization by theCalifornia Department of Health Care Services(DHCS) or the plan. Psychological care: Up to a total of 20 individualand/or group counseling sessions are reimbursable when delivered during the prenatalperiod and/or during the 12 months followingchildbirth.In addition, the following education and supportservices are offered by qualified providers throughthe Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program(CPSP):8 Health education services Nutritional services, including vitamin/mineralsupplementation, and breastfeeding educationand support Psychosocial servicesWhere Are Medi-Cal MaternityServices Delivered?Prenatal and Postpartum Care ServicesLimited information is publicly available on theprovision of prenatal and postpartum care forpregnant Californians with low incomes. In 2018,prenatal care for approximately one-third ofMedi-Cal deliveries was provided by Federallywww.chcf.org 3

SEPTEMBER 2020Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and look-alikes,9assuming all pregnant patients who received prenatal care at FQHCs and look-alikes in 2018 werecovered by Medi-Cal.10 Kaiser Permanente provided prenatal care for approximately 5% of deliveries paid for by Medi-Cal, assuming all those thatgave birth at Kaiser hospitals also received prenatal care through the Kaiser system.11 About 60%of people covered by Medi-Cal who gave birthhad prenatal care provided by private practicesand medical groups, including non-FQHC publicand district hospitals, community clinics, and theUniversity of California system. Fewer than 1.5% ofpeople whose delivery was covered by Medi-Calreported no prenatal care at all.12 Informationabout postpartum care is even more limited. Thelack of information on where pregnant people withMedi-Cal receive prenatal and postpartum carepresents challenges in understanding quality andaccess and in facilitating quality improvement.DeliveriesWho Provides Medi-Cal MaternityServices?Within Medi-Cal, physicians provide the majority ofprenatal and postpartum services, as well as deliveries. However, births attended by midwives, whodeliver babies both in and out of hospitals, havegrown across payer types by 52% since 2007. In2018, midwives attended 6.8% of Medi-Cal birthsand 16% of privately insured births in California.17In California, midwives can practice under two different professions, certified nurse-midwives (CNMs)or licensed midwives.18 In 2019, there were 753CNMs and 386 licensed midwives in California.19Despite reimbursement parity mandated by theAffordable Care Act, access to midwives remains achallenge.20 This is due to many factors, includingscope-of-practice laws that require physiciansupervision for CNMs.21Figure 3. Births, Medi-Cal vs. Non-Medi-Cal, byHospital Type, California, 2017As with non-Medi-Cal births, almost all (99.6%)births to people covered by Medi-Cal take placein hospitals.13 But these births are not distributedn hospitals189,747 as illustratedn 228,317equally acrossin Figure 3.Nearly 75% of births covered by Medi-Cal happen31%that offerat one-fourth of California’s hospitalslabor and delivery — about 150,000 births annuallyat 80 California hospitals.14University of CaliforniaCity/CountyDistrict2%4%1%10%Freestanding birth centers provide care for lowPayers40% model ofriskAllpatientsand typically use a midwiferycare. Deliveries in these centers have nearly quadrupled since 2007, but still comprise only 0.14% ofMedi-Cal births.15 Demand for birth center servicesoutstrips supply. Although managed care plansand Medi-Cal 16%FFS are required to contract with20% birthfreestanding birth centers, many freestandingcenters do not accept Medi-Cal patients, citing the7%lower reimbursement rates2%they receive compared7% 1%to commercially insured 1%patients. In addition, itis not clear Medi-Calthat there is active oversightPrivate of thisrequirement or a penalty for plansInsurancethat fail to offer3%their network.16a freestanding birth center in3% 1% storKaiserNonprofit5%7%13%3%18%54%All PayersNotes: In-hospital births at 237 hospitals that offer maternityservices. Nonprofit hospitals include church-related hospitals.Investor hospitals are for-profit. Kaiser Permanente hospitals arenonprofit. Non-Medi-Cal includes uninsured patients. Segmentsmay not total 100% due to rounding.Source: Custom data request, California Maternal Quality CareCollaborative, received June 14, 2019.California Health Care Foundationwww.chcf.org 4

20%ntersSEPTEMBER 2020Community Perinatal Health Workers are alsoimportant members of the care team, though theycannot bill directly. They include doulas,22 childbirth educators, and lactation consultants. Womencovered by Medi-Cal are slightly more likely toreport using a doula than those with commercialinsurance.23How Does Medi-Cal Pay forMaternity Services?Like birth centers, demand also exceeds supplyfor midwives and doulas, as depicted in Figure 4,and these gaps are more pronounced than amongpeople with private coverage (not pictured) dueto a greater interest among people with Medi-Calcoverage and more limited access.24For nearly all maternity care services, Medi-Calreimbursement rates are significantly lower thancommercial reimbursement rates. These reimbursement disparities also exist in other types ofcare, both primary care and specialties such asoncology and orthopedics, but maternity providerssee a much larger portion of Medi-Cal patientsthan do providers in most other specialties.25Figure 4. Gap Between Actual Use and Future InterestAmong Medi-Cal Recipients: Birth Centers, Midwives,and Doulas, California, 2016Definitely wantActually use20%17%11% 1%Birth centers6%DoulasNotes: Based on a statewide survey of 2,539 women who gavebirth in California hospitals in 2016. Medi-Cal respondents wereidentified based on a Medi-Cal record of a paid 2016 childbirthclaim.Source: Carol Sakala et al., Listening to Mothers in California: APopulation-Based Survey of Women’s Childbearing Experiences,National Partnership for Women & Families, September 2018.California Department of Health Care Services, MIS/DSS DataActually useWarehouse.Definitely wantFor details on how Medi-Cal pays for maternityservices, please see companion paper Medi-CalExplained: Paying for Maternity Services available fordownload on CHCF’s website.California Health Care FoundationUnder the fee-for-service system, providers arepaid directly by DHCS using the methodologiesdescribed below.Historically, Medi-Cal FFS rates are among thelowest in state Medicaid programs nationally.26However, DHCS provides supplemental paymentsto certain providers. For maternity services, FQHCsand hospitals that serve Medi-Cal and uninsuredpatients are each eligible for specific types of supplemental payments, which can provide a substantial revenue stream.Professional Reimbursement Under FFS11%MidwivesFee-for-ServiceRoutine, uncomplicated obstetric care is reimbursed in three ways:1. Globally, for providers who render totalobstetric care, which includes prenatal care,delivery, and postpartum care. Payment istriggered by the baby’s delivery and is all-inclusive for the obstetrician (e.g., routine urinalysis and ultrasounds are included and cannotbe billed separately). This approach simplifiesbilling and can enable a team-based collaborative practice between physician and nonphysician providers. Global billing is more oftenused by private practice providers and is nottypically used by FQHCs.2. Per visit, for providers who do not rendertotal obstetric care or who provide fewerthan 13 prenatal visits. Providers receive ahigher payment for the initial prenatal visit anda lower payment rate for follow-up visits (up to13) and one postpartum visit. Per-visit billingwww.chcf.org 5

SEPTEMBER 2020can result in a higher reimbursement per episode than global billing.3. Based on face-to-face time spent forComprehensive Perinatal Services Program(CPSP) services, which are additional toobstetric care services described above, withbonuses for early initiation of care. To be eligible, providers must enroll as a CPSP provider.FQHCs are reimbursed at their ProspectivePayment System (PPS) rate for CPSP servicesrather than according to the CPSP fee schedule.Other care, including mental health services andspecialty care, are provided on a fee-for-servicebasis.Facility Reimbursement Under FFSHospitals are paid through a facility-specific caserate that is adjusted based on the reason for admission, severity of illness, and risk of mortality. Thispayment system, All Patient Refined DiagnosisRelated Groups (APR-DRGs),27 builds on a similarsystem used in Medicare that was introduced in1983, but was developed with Medicaid populations in mind.28 In California, DHCS implementedAPR-DRGs in 2013.Freestanding birth centers are paid a flat ratefor deliveries that is about 35% of the averageAPR-DRG rate for low-risk vaginal births. If thepatient needs to be transferred to a hospital, thebirth center gets 25% to 75% of the rate, dependingon when the transfer occurs.How DHCS Pays Managed Care PlansPlans typically receive a monthly capitation amountfor every individual enrolled based on their aidcode. Importantly, specialty mental health andsubstance use disorder services are delivered byan enrollee’s county, distributing accountabilityand adding complexity to care coordination for ahigher-risk group of pregnancies.For counties with a single managed care plan, maternity spending is factored into monthly capitationrates paid by DHCS. For counties with more thanone plan, maternity services are treated differentlybecause births are high-cost events and may not beCalifornia Health Care Foundationevenly distributed between plans in a given year. Asa result, plans receive a supplemental payment forevery live birth, designed to cover the physician andfacility spending for the birth episode.29How Managed Care Plans Pay ProvidersIn interviews with seven Medi-Cal managed careorganizations conducted in fall 2019,30 many saidthey use the FFS schedule in determining payment,while others said they may pay 10% to 30% morethan FFS rates. Contracts vary by provider and areoften proprietary and confidential.In addition, some plans rely heavily on value-basedpayment mechanisms, such as global or professional services capitation to delegated medicalgroups.31 These risk-bearing groups use a combination of capitation and fee-for-service to paytheir contracted providers and, like managed careplans, vary in their rates and approaches, which areproprietary and confidential. Some stakeholdersraised concerns about access to CPSP services inmanaged care and the delegated environment,and there is very little publicly available data aboutuse of the program.What Experience and OutcomesDoes Medi-Cal Produce?Overall, compared to people covered by privateinsurance, those covered by Medi-Cal are muchless likely to access early prenatal care or robustpostpartum care, as illustrated in Figures 5 and 6on page 7.People covered by Medi-Cal were much more likelyto report feeling that they were treated unfairly inthe hospital because of the type of insurance theyhad, as shown in Figure 7 on page 7.In terms of birth outcomes, mothers covered byMedi-Cal are slightly more likely to deliver via c-section and to deliver babies with more complex needs.Like many in the general health care system,Medi-Cal members face challenges of timelyaccess to care, bias and racism in the health caredelivery system, and food and housing insecurity.www.chcf.org 6

der%der%LatinxWhiteFigure 5. Prenatal Care in the First Trimester by PayerAsianType andRace/Ethnicity Within Medi-Cal, California, 2018Black or African AmericanAsianMore than one race80% IslanderNative Hawaiian or Other PacificLatinxAmerican Indian or Alaska Nativemnmnmn79%Non Medi-CalWhiteMedicaid78%Private InsuranceMore than one race74%American Indian or Alaska NativeNative HawaiianOverall or Other Pacific Islander63%91%3%78%American.Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDCWONDER Online Databases, “Natality Public-Use Data, 20162018,” accessed February 11, 2020, and April 30, 2020.Figure 7. Unfair Treatment Due to Type of Insurance byPayer, California, 2016UsuallyAlwaysMedi-Cal5%2%2%Private1% 1% 1%Notes: Not all eligible respondents answered each item. “Never”not shown. Medi-Cal respondents were identified based upon aMedi-Cal record of a paid 2016 childbirth claim. Privately insuredrespondents self-identified in the survey. p .01 for differencesby payer.Sources: Listening to Mothers in California (statewide surveyof 2,539 women who gave birth in California hospitals in 2016),National Partnership for Women & Families, 2018; CaliforniaDepartment of Health Care Services MIS/DSS Data Warehouse.California Health Care Foundation3450%24% 9% 7%PayerMedi-Cal12%43%Private41%Latinx10%White7%25% 11% 9%58%Asian/Pacific IslanderPrivatePrivateNote: Sourcesuses Hispanic or Latinoand Black or AfricanInsuranceInsuranceSometimes29%9% rivate insurance31%Figure 6. Number of Maternal Postpartum Office Visitsby Payer and Race/Ethnicity, California, 20166%Blackn 228,317SEPTEMBER 202023% 7%6%22% 14% 15%45%26% 11% 8%57%22% 7%57%24% 7%5%5%Notes: Based on a statewide survey of 2,539 women who gavebirth in California hospitals in 2016. Medi-Cal respondents wereidentified based on a Medi-Cal record of a paid 2016 childbirthclaim. Source uses Latina.Source: Carol Sakala et al., Listening to Mothers in California: APopulation-Based Survey of Women’s Childbearing Experiences,National Partnership for Women & Families, September 2018.California Department of Health Care Services, MIS/DSS DataWarehouse.These factors result in heightened health risks,poorer outcomes, and poorer patient experiencesAlwaysfor pregnant people, and notably for Black pregnantUsuallypeople, as seen in Figure 8 on page 8. These dispariSometimesties cannot be fully explained by patient-level factorssuch as age, income, education level, insurancestatus, cesarean birth, or higher prevalence of comorbidities.32 Instead, the evidence points to multiplefactors at different levels, including health systemquality33 and the impact of racism and chronic stressduring pregnancy,34 including that coming from thehealth system35 and the individual provider.36In summary, California is a large state, home to oneeighth of the births that happen in the US annually.It is varied in both its geography and the racial andwww.chcf.org 7

SEPTEMBER 2020Figure 8. Perinatal Characteristics of Pregnant People with Medi-Cal Coverage, by Race/Ethnicity, California, 2018BlackAmerican Indian or Alaska NativeMore than one raceNative Hawaiian or Other Pacific IslanderLatinxWhiteAsian3632 32ann31 31 31 30racenander13C-section, %12 11 1213999Preterm birth, %12999797 31Low birthweight, %1011 11888NICU admission, %Notes: Source uses Hispanic or Latino and Black or African American.Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC WONDER Online Databases, “Natality Public-Use Data, 2016-2018,” accessedFebruary 11, 2020, and April 29, 2020.ethnic diversity of its population. While the Medi-Calhealth care system is highly complex, there are somethings it does very well. The success of its work toreduce maternal mortality and the c-section ratehave been held up as national models.California has also made important strides inrecent years to address maternal mental healthand pilot a more integrated approach for infantsand children born with special needs. While it istoo soon to assess the impact of these new policies, they represent progress, and it is important totrack their outcomes. Maternal mental health: In 2019, Medi-Calintroduced enhanced reimbursement for perinatal screening for depression. Postpartumdepression screening is also allowed as partof a well-child visit to be billed under theinfant’s coverage throughout the first yearof life. In addition, up to 20 individual and/or group counseling sessions for pregnant orpostpartum women with certain depressive,socioeconomic, and mental health–related riskCalifornia Health Care Foundationfactors are now covered. Finally, Senate Bill 104(Chapter 67, Statutes of 2019) authorized theextension of “pregnancy pathway” Medi-Calcoverage by 10 additional months beyond the60-day postpartum period for individuals whohave been diagnosed with a maternal mentalhealth condition. This new coverage was implemented August 1, 2020. However, unless furtherlegislative action is taken, the program may besuspended on December 31, 2021. Whole Child Model: As of July 2019, five planscovering 21 counties operate under the WholeChild Model. This model integrates coordination and financing for all required newborn careand the care of children with special health careneeds, historically carved out to the FFS systemunder California Children’s Services. Theseplans now bear neonatal intensive care unit(NICU) risk, which creates more of an incentiveto embrace value-based payment and/or innovative care models that improve outcomes andreduce costs in birth and infancy.www.chcf.org 8

SEPTEMBER 2020Endnotes1. We use the term “pregnant people” to recognize that notall people who become pregnant and give birth identifyas a woman or a mother.2. Author analysis of Fiscal Year 2017/18 MaternityKick Payments from “Rate Range Development andCertification Reports by Plan Model Type,” Department ofHealth Care Services, accessed June 15, 2020.3. Len Finocchio, Matthew Newman, and Eunice Roh,Medi-Cal Facts and Figures: Crucial Coverage for LowIncome Californians, California Health Care Foundation,February 2019.4. Elizabeth Hinton et al., 10 Things to Know About MedicaidManaged Care, Kaiser Family Foundation, December 16,2019.5. “Federal Poverty Level (FPL),” HealthCare.gov, accessedJuly 7, 2020.6. Pregnancy-related services include prenatal care, labor,delivery, postpartum care, family planning services, and services for other diagnoses, illnesses, or medical conditionsthat might threaten the safe, full-term delivery of the fetus.Pregnancy-related coverage qualifies as Minimum EssentialCoverage as required by the Affordable Care Act.7. Finocchio, Newman, and Roh, Medi-Cal Facts and Figures.8. Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program (CPSP) grewout of a perinatal demonstration project called theObstetrical Access Project, which operated from 1979 to1982 in 13 California counties. Comprehensive serviceswere shown to reduce low-birth-weight rate by one-thirdand to save approximately 2 in short-term neonatalintensive care unit costs for every 1 spent. CPSP servicesbecame a Medi-Cal benefit in 1987.9. An FQHC look-alike is a health center that meets allrequirements and is part of the Health Center Programbut does not receive federal award funding.10. Author analysis of California FQHCs from “2018 UniformData System (UDS) Resources,” Healthcare Resources andServices Administration, Bureau of Primary Health Care,accessed August 1, 2020.11. Jen Joynt, Maternity Care in California: A Bundle of Data,California Health Care Foundation, November 2019.12. Author analysis of Centers for Disease Control andPrevention, CDC WONDER Online Databases, “NatalityPublic-Use Data, 2016-2018,” accessed April 30, 2020.13. Author analysis of Centers for Disease Control andPrevention, CDC WONDER Online Databases, “NatalityPublic-Use Data, 2016-2018.”14. Author analysis of custom data request from the CaliforniaMaternal Quality Care Collaborative, received December17, 2019.15. Author analysis of Centers for Disease Control andPrevention, CDC WONDER Online Databases, “NatalityPublic-Use Data, 2016-2018.”California Health Care Foundation16. Blair Dudley, Promoting Midwifery and High Value Care inMedi-Cal, Pacific Business Group on Health, April 2020.17. Author analysis of custom data request from the CaliforniaMaternal Quality Care Collaborative, received December17, 2019.18. The professions share a philosophy of women-centeredcare that recognizes and supports childbirth as a normalphysiologic process, but differ in education requirements,certifying organizations, regulatory bodies, licensingpolicies, and enabling statutes. More detail is available atCalifornia’s Midwives: How Scope of Practice Laws ImpactCare.19. Connie Kwong et al., California’s Midwives: How Scopeof Practice Laws Impact Care, California Health CareFoundation, October 2019.20. Carol Sakala et al., Listening to Mothers in California:A Population-Based Survey of Women’s ChildbearingExperiences, National Partnership for Women & Families,September 2018.21. Kwong et al., California’s Midwives.22. Doulas are nonmedical professionals who provide emotional, physical, and informational support and guidancein different aspects of reproductive health. More detailis available from the National Health Law Program’s factsheet “What Is a Doula?” (PDF).23. Sakala et al., Listening to Mothers in California.24. Sakala et al., Listening to Mothers in California.25. Steve Zuckerman, Aimee Williams, and Karen Stockley,Medi-Cal Physician and Dentist Fees: A Comparisonto Other Medicaid Programs and Medicare, CaliforniaHealthCare Foundation, April 2009.26. Zuckerman, Williams, and Stockley, Medi-Cal Physicianand Dentist Fees.27. Department of Health Care Services, “Diagnosis RelatedGroup Hospital Inpatient Payment Methodology,” lastmodified April 8, 2020.28. Richard F. Averill et al., All Patient Refined DiagnosisRelated Groups (APR-DRGs), Version 20.0: MethodologyOverview (PDF), 3M Health Information Systems, 2003.29. Michael Engelhard, Steve Soto, and Athena Chapman,Medi-Cal Payment to Managed Care Plans — CurrentProcess and Challenges, California Health CareFoundation, February 2019.30. Plans interviewed included CalOptima, Community HealthGroup of San Diego, Health Net, Inland Empire HealthPlan, L.A. Care Health Plan, Partnership HealthPlan ofCalifornia, and Santa Clara Family Health Plan.31. Dudley, Promoting Midwifery and High Value Care inMedi-Cal.32. Elizabeth Howell, “Reducing Disparities in SevereMaternal Morbidity and Mortality,” Clinical Obstetrics andGyn

Still, from a cost perspective, maternity care is a relatively small piece of all that Medi-Cal covers. An estimate using median spending per live birth — about 7,000 — multiplied by the number of live births covered by Medi-Cal suggests that pregnant people1 make up 1.4% of Medi-Cal enrollees and