Transcription

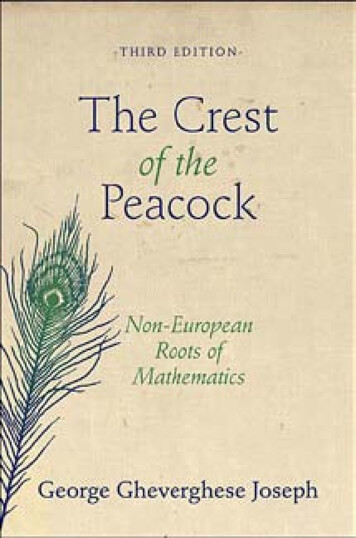

The Crest ofthe Peacock

The Crest ofthe PeacockNon-European Roots of Mathematics THIRD EDITIONGeorge Gheverghese JosephPrinceton University Press Princeton & OxfordPrinceton University Press Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2011 byPrinceton University PressPublished by Princeton University Press,41 William Street, Princeton,New Jersey 08540In the United Kingdom:Princeton University Press,6 Oxford Street, Woodstock,Oxfordshire OX20 1TWFirst published by I. B. Tauris 1991Published in Penguin Books 1992Reprinted with minor revisions 1993Reprinted with revisions 1994Reprinted with additional material 2000press.princeton.eduAll Rights ReservedLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataJoseph, George Gheverghese.The crest of the peacock : non-European roots ofmathematics / George Gheverghese Joseph. — [3rd ed.].Originally published: London ; New York : I.B. Tauris,1991.Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 978- 0- 691- 13526- 7 (pbk. : alk. paper)1. Mathematics Ancient. 2. Mathematics—History.I. Title.QA22.J67 2001510.9—dc222010015214British Library of Cataloging- in- Publication Datais availableThis book has been composed in MinionPrinted on acid- free paper Printed in the United States of America10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the memory of my parents and elder sister,Adangapuram Gheverghese Joseph Panicker,Sara Joseph, and Mary Jacob

Like the crest of a peacock, like the gemon the head of a snake, so is mathematicsat the head of all knowledge.—Vedanga Jyotisa (c. 500 bc)

ContentsPreface to the Third Edition xiPreface to the First Edition xxiiiChapter OneThe History of Mathematics: Alternative Perspectives 1A Justification for This Book 1The Development of Mathematical Knowledge 3Mathematical Signposts and Transmissions across the Ages 12Chapter TwoMathematics from Bones, Strings, and Standing Stones 30Beginnings: The Ishango Bone 30Native Americans and Their Mathematics 45The Emergence of Written Number Systems: A Digression 58Mayan Numeration 66Chapter ThreeThe Beginnings of Written Mathematics: Egypt 79The Urban Revolution and Its African Origins 79Sources of Egyptian Mathematics 81Number Recording among the Egyptians 84Egyptian Arithmetic 88Egyptian Algebra: The Beginnings of Rhetorical Algebra 102Egyptian Geometry 109Egyptian Mathematics: A General Assessment 119

viii ContentsChapter FourThe Beginnings of Written Mathematics: Mesopotamia 125Fleshing Out the History 125Sources of Mesopotamian Mathematics 132The Mesopotamian Number System 136Babylonian Algebra 150Babylonian Geometry 159Chapter FiveEgyptian and Mesopotamian Mathematics: An Assessment 177Changing Perceptions 178Neglect of Egyptian and Mesopotamian Mathematics 181The Babylonian- Egyptian- Greek Nexus: A Seamless Story orThree Separate Episodes? 184Chapter SixAncient Chinese Mathematics 188Background and Sources 188The Development of Chinese Numerals 198Chinese Magic Squares (and Other Designs) 206Mathematics from the Jiu Zhang (Suan Shu) 215Chapter SevenSpecial Topics in Chinese Mathematics 246The “Piling- Up of Rectangles”: The Pythagorean Theoremin China 248Estimation of p 261Solution of Higher- Order Equations and Pascal’s Triangle 270Indeterminate Analysis in China 282The Influence of Chinese Mathematics 296Chinese Mathematics: A Final Assessment 301Chapter EightAncient Indian Mathematics 311A Restatement of Intent and a Brief Historical Sketch 311Math from Bricks: Evidence from the Harappan Culture 317Mathematics from the Vedas 323Early Indian Numerals and Their Development 338Jaina Mathematics 349Mathematics on the Eve of the Classical Period 356

ContentsChapter NineIndian Mathematics: The Classical Period and After 372Major Indian Mathematician- Astronomers 373Indian Algebra 380Indian Trigonometry 392Other Notable Contributions 403Chapter TenA Passage to Infinity: The Kerala Episode 418The Actors 418Transmission of Kerala Mathematics 435Chapter ElevenPrelude to Modern Mathematics: The Islamic Contribution 450Historical Background 450Major Medieval Islamic Mathematicians 455Medieval Islam’s Role in the Rise and Spread of IndianNumerals 461Arithmetic in the Islamic World 466Algebra in the Islamic World 475Islamic Algebra and Its Influence on Europe 486Geometry in the Islamic World 487Trigonometry in the Islamic World 496Mathematics from Related Sources 503The Islamic Contribution: A Final Assessment 508References 521Name Index 543Subject Index 549ix

Preface to the Third EditionIt is now almost twenty years since the first edition of this book came outas a hardback. Four reprints, two editions, and a number of translationslater, the book is badly in need of a revamp, owing to new theories andevidence as well as comments, suggestions, and criticisms that have comefrom so many different parts of the world. It was particularly fortuitousthat while I was preparing the new edition of the book there appeared TheMathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook(edited by Victor Katz), on the history of mathematics of the named cultures, published in 2007. My debt to this book will become evident fromthe references and acknowledgments that follow.The readership of this book in the past has included mainly teachersand the general public, with the technical content of the mathematicalmaterial being accessible to anyone having a reasonable precalculus background. And since it is a similar readership that this edition addresses,the demands on the reader have been kept to a level not different fromthose of the earlier editions. However, it is hoped that the new edition willalso attract greater interest among the historians of mathematics. Towardthat end, and for other readers who wish to pursue their interests further,this edition contains a major innovation: the introduction of endnotes foreach chapter. These endnotes will hopefully serve different objectives: toprovide references for those who wish to pursue their own reading on specific subjects, to qualify and elaborate on points made in the main text,to respond to comments and criticisms on earlier editions, and occasionally to make connections between different traditions and their “ways ofdoing mathematics.” It is hoped that the introduction of these endnoteswill not disturb or distract the flow of the narrative in the main text. Yet

xii Preface to the Third Editionanother innovation with this edition is a revised and enlarged referencelist. Because of substantial additions, it was felt necessary to regroup theentries according to the mathematics of particular cultures, with a separatecategory for general items. It is hoped that these innovations will make thisbook a more effective resource for students and teachers of mathematicswhile remaining accessible to general readers.While researching for this edition, I also came across another book, AHistory of Mathematics: From Mesopotamia to Modernity, by Luke Hodgkin. In its introduction, there is a section on “Eurocentrism,” which I foundboth thought provoking and persuasive. Incidentally, Hodgkin’s book isthe first history of mathematics I have come across that acknowledges thepervasiveness and durability of the Eurocentric version of history. Thequotation below from his book encapsulates his view:It would appear that the argument set out by Joseph [in the Crest of thePeacock] has not been won yet. . . . For what [Eurocentrism] might meanin mathematics, we should go back to Joseph who, at the time he began hisproject (in the 1980s), had a strong, passionate and undeniable point. . . .his book is important: it is the only book in the history of mathematics written from a strong personal conviction, and it is valuable for thatreason alone. It stands as the single most influential work in changing attitudes to non- European mathematics. The sources, such as Neugebaueron the Egyptians and Babylonians, or Youschkevitch on the Islamic tradition, may have been available for some time before, but Joseph drew theirfindings into a forceful argument which since (like Kuhn’s work) its mainthrust is easy to follow has made many converts. (pp. 12–13)A number of “mainstream” historians of mathematics have in recent yearstaken up the task of casting a wider net in writing history and consideringseriously the contributions of not only the ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations but also the Chinese, Indian, and Islamic civilizations.There are substantial and growing communities of mathematics historiansof all these civilizations, a number of whom are engaged in the task ofmaking new evidence accessible to everyone. Nevertheless, it is argued thatchange in historical perceptions is slow, and that a significant part of thenew studies in the history of mathematics has failed to reach the broadercommunity.A central theme of the earlier editions, seen by some as their principalstrength and by others as either an irritating irrelevance or even a fatal

Preface to the Third Edition xiiiweakness, is their critique of the widespread acceptance of the hegemonyof a Western version of mathematics, following from the assumption thatmathematics was largely a Greek and European creation. I have arguedelsewhere that in the past the two tactics used to propagate this view were(1) omission and appropriation and (2) exclusion by definition. The first isexamined in some detail in chapter 1. The second needs clarification andelaboration here.A Eurocentric approach to the history of mathematics is intimately connected with the dominant view of mathematics, both as a sociohistoricalpractice and as an intellectual activity. Despite evidence to the contrary,a number of earlier histories viewed mathematics as a deductive system,ideally proceeding from axiomatic foundations and revealing, by the “necessary” unfolding of its pure abstract forms, the eternal/universal laws ofthe “mind.”The concept of mathematics found outside the Graeco‑European praxiswas very different. The aim was not to build an imposing edifice on a fewself‑evident axioms but to validate a result by any suitable method. Some ofthe most impressive work in Indian and Chinese mathematics examined inlater chapters, such as the summations of mathematical series, or the use ofPascal’s triangle in solving higher- order numerical equations, or the derivations of infinite series, or “proofs” of the so- called Pythagorean theorem,involve computations and visual demonstrations that were not formulatedwith reference to any formal deductive system. The view that mathematicsis a system of axiomatic/deductive truths inherited from the Greeks, andenthroned by Descartes, has traditionally been accompanied by the following cluster of values that reflect the social context in which it originated:1. An idealist rejection of any practical, material(ist) basis for mathematics: hence the tendency to view mathematics as value‑free anddetached from social and political concerns2. A n elitist perspective that sees mathematical work as the exclusivepreserve of a high‑minded and almost priestly caste, removed frommundane preoccupations and operating in a superior intellectualsphereMathematical traditions outside Europe did not generally conform tothis cluster of values and have therefore been dismissed on the groundsthat they were dictated by utilitarian concerns with little notion of rigor,

xiv Preface to the Third Editionespecially relating to proof. Any attempt at excavation and restoration ofnon‑European mathematics is a multifaceted task: confront historical bias,question the social and political values shaping the mathematics (and thewriting of the history of mathematics), and search for different ways of“knowing” or establishing mathematical truths in various traditions. I havewritten elsewhere (Joseph 1994b, 1997a) on the same subject in relationto the Indian tradition. (Documentation can be found in the “India” and“General” sections of the reference list at the end of this book.) Because ofthe centrality of the issue of “proof ” in judging the quality of mathematicsoutside the European tradition, we will be returning to this subject at different points in this book.The responses of some critics to the earlier versions of this book havehelped to confirm my belief that words or labels in common use need careful scrutiny. It has been pointed out that terms such as “Classical,” “DarkAges,” and “Renaissance” are peculiarly European concepts of little relevance to the rest of the world. Also, words such as “ancient,” “medieval,”and “modern” are of doubtful provenance when applied to other histories. It is, however, in the labeling of geographical areas that the distortionscould, potentially, take on grotesque proportions.Consider the term “Europe.” A Eurasian peninsula has been elevatedto the status of a continent, equal in importance, if not superior, to therest of the continent combined. The Mercator projection may have contributed to this perception, with its visually distorted image exaggerating thenorthward bounds to make “Europe” look larger than the whole of Africa,and enormous compared with the other Eurasian peninsula, India. Thespecial status accorded to Europe in the standard histories of the world hasstrengthened the notion, shared by many Europeans and their overseas descendants, that they played a starring role in the Eurasian theater of worldhistory. The resulting categories such as European/non‑European, West/East, Europe/Asia have tended to reinforce this Eurocentric illusion.It is precisely because of this tendency to enhance Europe through theuse of labels that any project involving the writing of a balanced historyshould carefully address the question of labels. Unfortunately, these labelshave existed for so long that they have acquired legitimacy through usage. Fairly early in writing The C

book a more effective resource for students and teachers of mathematics while remaining accessible to general readers. . Ages,” and “Renaissance” are peculiarly European concepts of little rele-The Crest of the Peacock. Non‑European Roots of Mathematics, , . George Gheverghese Joseph . The Crest of the Peacock) (The : mathematics: ‑ to ‑ The Crest of the Peacock. , of (1), (1 .File Size: 2MBPage Count: 592