Transcription

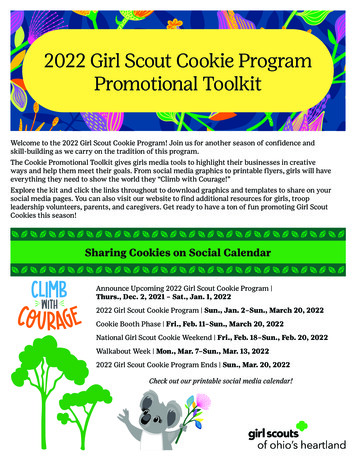

A salute to Alexander Calder sculpture,watercolors and drawings, prints,illustrated books, and jewelry in thecollection of the Museum of Modern Art.Introductory essay by Bernice RoseAuthorCalder, Alexander, 1898-1976Date1969PublisherThe Museum of Modern ArtExhibition URLwww.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1931The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—isavailable online. It includes exhibition catalogues,primary documents, installation views, and anindex of participating artists.MoMA 2017 The Museum of Modern Art

ASALUTETOALEXANDERCALDER

I

ASALUTETOALEXANDERCALDERSCULPTUREWATERCOLORSAND DRAWINGSPRINTSILLUSTRATEDBOOKSAND JEWELRYIN THE COLLECTION OFTHE MUSEUMOF MODERN ARTINTRODUCTORYESSAYBYBERNICEROSETHE MUSEUMOF MODERN ART,NEW YORK

HA0r(The quotation from Thomas Wolfe'sYou Can't Go Home Againis reprinted by permission ofHarper & Row, Publishers, Inc.OioQuotations fromCalder-. An Autobiography with Picturesare reprinted by permission ofPantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc.Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 72-1 10987The Museum of Modern Art11 West 53 StreetNew York, N.Y. 10019 1969 by The Museum of Modern Art. All rights reservedPrinted in the United States of AmericaOP IARTJon the coverMODEL FOR "TEODELAPIO." (1962)oppositeAlexander Calder, Roxbury, Conn., 1959(photo Alexander Liberman)

A SALUTE TO ALEXANDER CALDERThroughout his long career as one of the pioneeringsculptors of the twentieth century, Alexander Calder hasbeen unusually reticent, making very few statementsabout his work and theorizing as little as possible whenhe could be persuaded to speak. "When an artist explains what he is doing," he wrote in 1937, "he usuallyhas to do one of two things: either scrap what he hasexplained, or make subsequent work fit in with the explanation. Theories may be all very well for the artisthimself, but they shouldn't be broadcast to other people."Calder remains reticent to this day. But, while he hasleft to others to theorize about his sculpture, the sculpture itself has generated its own definitions. In theAddenda Section of the Second Edition of Webster'sNew International Dictionary published in 1954 there aretwo definitions that had not appeared in earlier editions:mobile n. Art. A delicately balanced construction orsculpture of a type developed by Alexander Caldersince 1930, usually with movable parts, which can be setin motion by currents of air or mechanically propelled,stabile n. Art. An abstract sculpture or construction typically made of sheet metal, wire, and wood. Cf. MOBILEabove LOBSTERTRAP AND FISH TAIL. (1939)opposite WHALE II. (1964)4In subsequent editions the definitions no longer makedirect reference to Calder, indicating that his work hadgenerated a whole new genre of objects, so integratedthat they were classified as part of the general vocabulary. These are definitions that can be applied only tosculpture made in the twentieth century and only tosculpture set within a fairly specific context, and withcertain definite roots. The roots most meaningful hereare Constructivism, an art movement based on the analytic structure of Picasso's Cubist collages; Futurist ideasthat demanded that art portray space through dynamicmovement and use industrial materials appropriate to anage of speed; and Malevich's rejection of the portrayalof objects as necessary to art.Calder was, perhaps, peculiarly qualified to realizethe ideas of the Constructivists and at the same timesynthesize them with Surrealism. Son and grandson ofsculptors, he himself had been trained as a mechanicalengineer. He was thus familiar with both technology andart when he arrived in Paris in the late twenties, and wason the scene during a major revival of interest in nonobjective art, Constructivism, and Dada.Calder's first fame came from his performance of hisminiature circus before the avant-garde. The impact thecircus had on these intellectual and social circles is per-

haps best indicated by the circumstance that years laterThomas Wolfe, in his novel You Can't Go Home Again,would use a performance of the circus as a focus for hisstinging comment on a social milieu that used art andartists as a diversion."Yes, Mr. Piggy Logan was the rage that year. He wasthe creator of a puppet circus of wire dolls, and theapplause with which this curious entertainment had beengreeted was astonishing. Not to be able to discuss himand his little dolls intelligently was, in smart circles, akinto never having heard of Jean Cocteau or Surrealism;it was like being completely at a loss when such namesas Picasso and Brancusi and Utrillo and Gertrude Steinwere mentioned. Mr. Piggy Logan and his art werespoken of with the same animated reverence that theknowing used when they spoke of one of these—"The highest intelligences of the time—the very subtlestof the chosen few —were bored by many things —They were bored with living, they were bored with dying, but— they were not bored that year with Mr. PiggyLogan and his circus of wire dolls.".There were miniature circus rings made of roundedstrips of tin or copper which fitted neatly together. Therewere trapezes and flying swings. And there was anastonishing variety of figures made of wire to representall the animals and performers. There were clowns andtrapeze artists, acrobats and tumblers, horses and bareback lady riders. There was almost everything that onecould think of to make a circus complete, and all of itwas constructed of wire —"It started, as all circuses should, with a grand procession of the performers and the animals in the menagerie. Mr. Logan accomplished this by taking eachwire figure in his thick hand and walking it around thering and then solemnly out again. . . ."Then came an exhibition of bareback riders. Mr.Logan galloped his wire horses into the ring and roundand round with movements of his hand. Then he put theriders on top of the wire horses, and, holding them firmlyin place, he galloped these around too. Then there wasan interlude of clowns, and he made the wire figurestumble about by manipulating them with his hands. Afterthis came a procession of wire elephants. . . ."above THE HORSE. (1928)The Horse is an early combination carved-and-constructed piece-, itprefigures the structure of the later metal stabiles."Metal is more flexible for shapes, shapes in wood are limited by thegrain." (Conversation)below COW. (1929)"The form isn't very elegant." (Conversation)6These performances provided Calder not only withmoney to eat but with introductions to the most advanced artists of the time. In Paris he met Miro (althoughhe did not immediately assimilate the significance ofMiro's work), and ultimately Arp, Leger, and other members of Abstraction-Creation,the exhibiting group ofthe Neo-Plasticists and Constructivists in Paris. Graduallyhe turned the emphasis away from the circus and began

SODA FOUNTAIN. (1928)THE HOSTESS.(1928)7

above COW. (1929)below SOW. (1928)8to construct and exhibit large wire figures. JosephineBaker was the first subject to be treated in this largeformat. Though many of the wire sculptures are caricatures, they are—the portraits in particular— the first sculptures in which Calder makes use of multiple views,constructs a sculpture in which all sides can be seen atonce, and modulates space as if it were a palpablevolume.It cannot be claimed that Calder was pursuing anyradically new, original course in sculpture at this time.Open-form sculpture was under constant discussion during these years; with the collaboration of Gonzalez,Picasso was also working with wire. But, whereas hewas soldering and using wire as a stiff, sticklike element,Calder, who has always preferred mechanical constructions, was creating in the manner that has remainedcharacteristic for him. He has always found it easier tothink with his hands, to think in terms of specific materials. He bends and twists wire to outline planes andvolume and follow features as if wire were a fluid linedrawn in space. The flexibility of these wire figures showsthat from the first Calder displayed a propensity for moving form. He had become so facile with wire representations that he could make a piece like Sow on demand infifteen minutes. But, by 1930, he was ready for new challenges. An earlier piece of 1928, Elephant Chair withLamp, already shows elements of much later standingmobiles: a fixed organic form for a base, a wire armextended from the apex, with mobile elements suspendedfrom it. Calder quickly began to move into new areas.It is at this time that Constructivist ideas seem to haveprovided him with a new context for open-form sculpture. Constructivism had originated in Russia during theRevolution with the brothers Naum Gabo and AntoinePevsner, who spread its ideas first to Germany and thento Paris during the twenties. In both countries it hadsignificant effects, becoming a focus for plastic innovations. In 1920 Gabo had written the Realistic Manifestoin which he announced the Constructivist break with theplastic tradition that had dominated Western art for"1000 years." Among his pronouncements are severalthat seem appropriate to Calder:"The realization of our perceptions of the world inthe forms of space and time is the only aim of our pictorial and plastic art. we construct our work as theuniverse constructs its own, as the engineer constructshis bridges, as the mathematician his formula of theorbits. everything has its own essential image — all[are] entire worlds with their own rhythms, their own

JOSEPHINE BAKER. (1927-29)"I never met Josephine Baker , but I had a friend, a Texas musician,Renick Smith, and I did some drawings for music covers. Smith took themaround Paris to the greatest American singers and the only one who woulddo anything was Josephine Baker. . . . She had a beautiful body. . .when Ishowed her to someone one time, he said, 'That's her beautiful body ?(Conversation)

MARION GREENWOOD. (1929-30)"Where you have features you draw them, where there areri t any, youlet go." (Conversation)orbits." Denouncing descriptive line and volume, Gabocontinued: ".we bring back to sculpture the line as adirection and in it we affirm depth as the one form ofspace. We renounce the thousand-year-old delusion inart that held the static rhythms as the only elements ofthe plastic and pictorial arts. We affirm in these arts anew element of the kinetic rhythms as the basic formsof our perception of real time." Later he expanded hisideas to deal directly with the materials of sculpture: "Insculpture, as well as in technics, every material is goodand worthy and useful, because every material has itsown aesthetical value. In sculpture, as well as in technics, the method of working is set by the material itself."In 1930 Calder was invited to join the AbstractionCreation group. In the same year, Mondrian came tosee his circus; Calder returned the visit, precipitatingthe first major change in his style."I was very much moved by Mondrian's studio," hewrote, "large, beautiful and irregular in shape as it was,with the walls painted white and divided by black linesand rectangles of bright color like his paintings. It wasvery lovely, with a cross-light (there were windows onboth sides), and I thought at the time how fine it wouldbe if everything there moved; though Mondrian himselfdid not approve of this idea at all. I went home andtried to paint. But wire, or something to twist, or fear, orbend, is an easier medium for me to think in." He wentback to wood and wire because he "liked manipulatingpieces."Calder is that rare individual who is able intuitivelyto integrate theory and concept with manual dexterity tocreate a "mechanical" representation of a visual idea.From Mondrian he learned the essentials of Neo-Plasticism, excerpting what he found useful: flat planes; theuse of primary colors in opposition to black and white;equilibrium of space and surface through proportion ofline, plane, and color; and, non-symmetrical balance:"the balanced relation is the purest representation ofuniversality."Calder immediately translated this experience into aseries of wood-and-wire constructions, which were exhibited at the Galerie Percier in 1931. One of theseconstructions was the prototype for the motorized mobile A Universe. Calder was now making a sharp distinction between these wire-and-wood non-objective constructions of 1931 and the earlier wire portraits, whichthe gallery owner insisted he show along with them.Calder's recent remark that he didn't consider the Cowa very elegant form is revealing: he had begun to think

ELEPHANTCHAIR WITH LAMP.(1928)CAT LAMP.

A UNIVERSE. (1934)"The orbits are all circular arcs or circles. The supports have been paintedto disappear against a white background to leave nothing but the movingelements, their forms and colors, and their orbits, speeds and accelerationsThe aesthetic value of these objects cannot be arrived at by reasoning.Familiarization is necessary." (Statement, 1934)12primarily in terms of forms rather than representations,hence the distinction.The Mondrians that had initiated the change in Calder's formal approach were rectangular, but as soon asCalder turned to three dimensions he thought in termsof round shapes. "Two hoops of wire intersecting forma sphere., .a sphere is one of the most elementary shapes.like drops of water." Calder has connected the ideaof spheres and elementary shapes with the idea of theuniversality of form and the universe itself in a verypragmatic interpretation of Gabo's statements. Plasticart was universal art, and the idea of the universe, itselfa moving system, led him into movement. In a statementof 1951 he wrote: ".the underlying sense of form inmy work has been the system of the Universe, or partthereof. For that is a rather large model to work from.What I mean is the idea of detached bodies floating inspace, or different sizes and densities, perhaps of different colors and temperatures, surrounded and interlarded with wisps of gaseous condition, and some atrest, while others move in peculiar manners, seems tome the ideal source of form."Calder's transition into mechanical movement in theseries of manual and motorized mobiles shown in Parisat the Galerie Vignon in 1933 should be seen in terms ofhis multi-faceted background. Perhaps first is his trainingas a mechanical engineer, which has grown rather thandiminished in importance. "I was studying a lot of theoryand didn't see what use it would be," he has remarked,"but it comes out." The mechanical engineering is notjust practically important, for building motors, for example,- it is conceptually important. A mechanical engineerstudies machines from the point of view of efficient motion,- he is technically concerned with kinetic theories,including the movement of liquids and gases. Perhapsas important were Gabo's ideas about a kinetic art. Although Calder did not meet Gabo during the Abstraction-Creation years, there can be no doubt that his ideasfor the creation of a kinetic art in four dimensions—thefourth dimension being the time interval inherent in anymovement sequence—were a major factor in Calder'swork, even at second hand. He may even have heardabout Gabo's one kinetic construction of 1920. AlthoughCalder did not meet Duchamp until after he made hisfirst mechanized constructions, he knew Picabia, andthrough Picabia he may have heard of Duchamp'searlier mechanized constructions. While Picabia's ownDada machine portraits are collages, not kinetic constructions, it is also probable that their Dada irony (and

THE BICYCLE. (1968. Free reconstruction of "THE MOTORIZED MOBILETHAT DUCHAMP LIKED" of co. 1932)"Disparity in form, color, size, weight, motion is what makes a composition.It is the apparent accident to regularity which the artist actually controlsby which he makes or mars a work." (Autobiography)"I call it Bicycle because the movement of that bottom part—reminds meof a bicycle." (Conversation)13

GIBRALTAR. (1936)opposite MORNING STAR. (1943)"Names are tags—my things are named later. Before the 1943 MOMAshow, when Sweeney insisted things should have names, I used to make alittle drawing when talking about a thing instead of using a name. AMorning Star—it's not a star—is a medieval weapon thrown from a horsesort of a lance with a round head and little spikes." (Conversation)14even the collage technique) had a strong effect on suchpieces as The motorized mobile that Duchamp liked andthe other motorized pieces of the next few years whichmove in somehow playful, apparently accidental orirrational patterns.One catalyst that may have helped to integrate theseexperiences was Calder's fortuitous viewing in 1928 ofan exhibition of automata taking place in the same building where an exhibition of his own was being held, although he probably knew automata before this time. Thecircus, while not mechanized, is mechanical and, in onesense, a collection of automata. It was a re-creation ofa whole world; although, as has been pointed out, itsawkwardness, lack of verisimilitude, and the occasionalfailure of a piece to perform permits it to be art, thustaking it out of the range of automata which aim at verisimilitude and perfect mechanical performance. The circus is in fact a parody of mechanical toys, a combination of "natural" and mechanical movement.It is, then, not illogical that at the same time that Calderexplored mechanized movement he began to make airdriven mobiles. Within the next few years the generalcult of faith in the machine as a panacea was to breakdown under the assaults of Dada and the Surrealists. Asthe machine cult broke down, Calder became more andmore sympathetic to Arp, whom he knew from Abstraction-Creation, and Miro, and gradually introduced biomorphic forms, which he added to his geometric shapes.These Surrealist affinities are evident in the work of thelate thirties and early forties and account for his inclusion in the Exposition Internationale du Surrealisme heldin Paris in the summer of 1947. At one point Calder evenused found objects for his mobiles but abandoned thatbecause it "was a concession to other people's ideas."Pieces like Gibraltar, Morning Star, and the series ofConstellations are among his most overtly Surrealist constructions.The mobile, Calder's first major mode, represents amajor breakthrough for modern sculpture. While the Futurists theorized, and Gabo, after one attempt, abandoned kinetic, motor driven sculptures as too primitive,Calder began seriously to explore the possibilities of kinetic sculpture. Between 1931 and 1938, as Jack Burnham, citing George Rickey, in his Beyond Modern Sculpture writes: "Calder in all seriousness explored a considerable area of present Kinetic activity before settling onthe hanging mobilesIt may be helpful to name. thedevices . Calder used in principle: in Kinetics some ofthese are sticklike and unstable objects hung in front of

15

above SWIZZLE STICKS. (1936)opposite SNOW FLURRYI. (1948)16a panel producing random shadow effects [SwizzleSf/cks], sculptures propelled by pumped liquids, belt andwheel systems as an integral part of a sculpture, constructions in which elements are interchangeable byhand, the use of hand-driven cams and crank trains plusmotorized animation of coiled springs."While Calder has continued to make motor-drivensculpture occasionally since his major machine period ofthe thirties, it is the air-driven mobile that has dominatedhis kinetic work. One reason he concentrated on naturalmovement was that he found motors "too much bother—they always needed fixing," but now he feels that hemight have continued if he hadn't had to make his owngear-reduction mechanisms, a process that was too boring and time-consuming. He does not feel, as do someother kinetic sculptors, that motors do not permit variedenough movements; he still believes, as he did in 1937,that with a motor one can produce a "positive instead ofa fitful movement," and that the combination of differentelements and movements, although simple, if variedenough in period, can give enough variety so as to bequite interesting.With the air mobiles he found metal a more flexiblematerial for shapes than wood; but more obviously, ifair currents are to produce movement, the resistance ofa flat surface is more efficient than that of a sphere. Thepieces are arranged so that they operate on the sameprinciple as sails: when pushed by the air a vertical piecemoves horizontally, a horizontal piece rises. The opposition of horizontal and vertical pieces will producevarying movements, and a series of either, or both kinds,will increase the complexity and duration of the movement. However, a vertical and horizontal cannot becombined on the same arm because they would worktoo much against each other: each works best with onekind of wind. Yet the manner in which they are hung, andthe combinations, make them capable of more complexmovement. As Rickey points out, these can be: linearmovement, up, down, and across (horizontal), and rotations around these three centers,-Calder's mobiles do notmove around centers lying outside of themselves. (Coloris an integral part of Calder's plastic images and, farfrom being incidental, adds still another variable to themotion sequence.)Another example of Calder's engineering training ishis use of torsion: a slight twist to the opposite directionin a piece of wire interrupts the equilibrium of a straightpiece and makes it more susceptible to movement. Calderuses this principle in wire bases and also in the reverse

above SPIDER.(1939)opposite MAN-EATER WITH PENNANTS. (1945)18twist that forms the loop in the wire arms on whichgroups of elements are suspended. His pieces are constructed on the principle of non-symmetrical equilibrium,depending on the wind to disrupt balance and overcomeinertia. At that point the elements of the mobile will follow a chain of cause and effect in a series of connectedtrajectories until they have completed the series andcome to rest. For Calder the balancing process has become largely intuitive, but is quite exact: his monumentalmobiles are made by mathematical enlargement from themodel and usually work right the first time. It is in his useof the principle of equilibrium (as stated by Mondrian)that Calder holds to his idea of the universal model.The first air mobiles were hung from the ceiling, butCalder quickly invented several standing varieties. Oneof these types, Sandy's Butterfly, has been called a mobilestabile. Calder objects strongly to this term because hefeels that "anything that moves is a mobile. There aretwo ways to make something move—suspend it from theceiling or balance it on a point." Again, ". . . there is theidea of an object floating unsupported— the use of a verylong thread— or a long arm in cantilever as a means ofsupport seems to best approximate this freedom from theearth."It is interesting to note that at rest many of the hangingmobiles, the early ones, in particular, can be lined up inone plane. Constructivists projected depth by arrangements of planes, but Calder relies on controlled chanceto arrange his planes in space. Many of the standingpieces are constructed more deliberately in three dimensions (and this has been carried into the later mobiles)but always of elements hung either vertically or horizontally.It is clear that the problem of support for moving sculpture led Calder into a direct attack on the formal basewhich had always supported sculpture and which hadproved a problem for the Constructivists. Gabo had rejected ceiling-hung sculpture; Calder accepts it withoutreservation, and he has even suspended mobiles fromthe wall. In the large standing mobiles Calder has integrated the base with the sculpture; the base takes on theattributes of sculpture but remains, at the same time, abase. The earliest versions of the standing base are inwire, or pipe, with the mobile elements cantilevered froma central spoke. Pole-supported mobiles such as ManEater are perhaps the closest Calder has come to a virtually base-less standing mobile.A later, more monumental version of the standingmobile base is a sheet steel pyramid of either open or

above CONSTELLATION WITH REDOBJECT. (1943)"In 1943, aluminum was being all used up in airplanes and becomingscarce. I cut up my aluminum boat. . and used it for several objects. I alsodevised a new form of art consisting of small bits of hardwood carved intoshapes and sometimes painted, between which a definite relation wasestablished and maintained by fixing them on the ends of steel wires. Aftersome consultation with Sweeney and Duchamp, who were living in NewYork, I decided these objects were to be called 'constellations.' "(Autobiography)opposite SANDY'S BUTTERFLY.(1964)20closed construction with the mobile arms cantileveredfrom the apex (Sandy's Butterfly). The base works not justas support but as foil to the moving elements, not competing with them but providing a dynamic tension between stability and mobility, massive form and open form,lightness and weightiness. This type of base is very clearlydistinguishable from a stabile. While the stabile establishes as few contact points with the ground as possible,the base of the standing mobile rests flat to the groundplane,- the suggestion of freedom from the earth is concentrated up toward the apex where the mass diminishesabruptly and the movement takes place. In another direction, Calder seems to have used certain formal elementsof the stabiles as bases for standing mobiles. It is in thesemobiles that base and sculpture are most completely integrated and that the standing mobiles look most like organisms. In fact, the names are frequently animal or, likeMyxomatosis, are connected with animals.The stabile —as dictionaries now define it —is the second major mode of Calder's oeuvre. It is difficult to determine the origins of the stabile. Although Calder hasadopted the term for all his stable sculpture, the openform wire constructions shown at the Galerie Percier, towhich Arp later gave the name "stabiles"— in contrast toDuchamp's name "mobiles" for the motorized constructions—are quite different; but the stabile appears to haveits genesis in certain elements of the hanging mobile.In 1934 Calder had moved away from strictly geometric shapes and was using "quasi-organic" forms inthree dimensions, hanging them from mobiles. The elements themselves seem logical extensions of some ofArp's Surrealist constructions, or three-dimensional renderings of some of Miro's forms. No doubt, floor-standingmetal sculpture of Picasso and Gonzalez lurks somewhere in the background. The organic character of theseforms seems to have dictated that they be constructed inthree dimensions. The Whale of 1937, the first of the largestabiles, seems to have come from the idea of placingone of these organic elements on the ground. It is as ifthe organic quality of the object was so suggestive of anobject in nature that it had to find a resting place: theground plane. However, Whale balances rather precariously on two points; Calder wants the sculpture to appear to rest as lightly as possible on the ground, toappear to rise from the ground or to be capable of instantaneous motion. Whale seems to undulate as it rises.In Whale, Calder had not yet quite achieved a perfectbalance of heavy mass on the ground plane with thefewest possible contact points as support, and the log

takes the place of traditional base supplying additionalsupport. The large stabiles, then, provide other kinds ofexperience in movement and space: arrested movement,different kinds of space as the spectator moves aroundthe object, sudden angles and planes that cut and dividethe space which create differently shaped forms.Calder had been experimenting with ideasfor environmental and over life-scale sculpture for several yearsbefore he made the first large-scale outdoor stabiles,Whale, and Black Beast of 1940. His first experience withlarge- or over life-scale had been in 1935 when he designed theater decor for Eric Satie's Socrate and MarthaGraham's dance company. He recalls being interestedin a mechanical ballet, without dancers, full-scale, usingmoving objects, for which he built a small model in Parisin 1936. Thus, the earliest models for large-scale sculpture, which date 1936—38, are motorized constructions,and somewhat theatrical. Each element stands separately, like an actor or dancer, somehow recalling OskarSchlemmer's Triadic Ballet. The only one of these earlyworks to be realized at the time was a "ballet" for the1939 New York World's Fair which used programmedjets of water. (In 1962 one of the motor-driven pieces,Four Elements, was built in Stockholm.) The difficulty ofrealizing these works at the time was both technical andfinancial.The same is true of the first large stabiles. The originalversions of Whale and Black Beast were in light-gaugemetal (Whale was aluminum,-Beast, steel), bolted so thatthey could be taken apart easily and moved for exhibition. It is possible to cut lightweight material directly,manually or with a hand-held power tool, then bend andbolt it or make manual staples to hold the pieces together. Calder does not solder and does not approve ofsoldering. Possibly he considers it a non-mechanicaltechnique,- an any case, he has, by preference, alwaysconstructed mechanically. However, in a large-scale workthe result is structural instability,- there is a tendency toward buckling and spreading at the seams and jointswhich distorts the appearance and offends the goodworkman in Calder. Calder wants the stabiles to be "asmassive as possible," which would seem to make theirappearance of resting lightly on the earth a contradiction—a triumph of art over matter. His first opportunity tomake a large-scale work in heavy material came in 1957when the architect Eliot Noyes commissioned a copy ofBlack B

AND JEWELRY IN THE COLLECTION OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART INTRODUCTORYE SSAYB Y BERNICERO SE THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK. The quotation from Thomas Wolfe's You Can't Go Home Again is reprinted by permission of Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. Quotations from Calder-. An Autobiography with Pictures