Transcription

HOOVERDIGESTRES EARCH O PIN IO NO N PUB LIC PO LICYS UMME R 2021 NO. 3T H E H O OV E R I N S T I T U T I O N S TA N F O R D U N I V E R S I T Y

The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace was establishedat Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, a member of Stanford’spioneer graduating class of 1895 and the thirty-first president of the UnitedStates. Created as a library and repository of documents, the Institutionenters its second century with a dual identity: an active public policyresearch center and an internationally recognized library and archives.The Institution’s overarching goals are to:» Understand the causes and consequences of economic, political,and social change» Analyze the effects of government actions and public policies» Use reasoned argument and intellectual rigor to generate ideas thatnurture the formation of public policy and benefit societyHerbert Hoover’s 1959 statement to the Board of Trustees of StanfordUniversity continues to guide and define the Institution’s mission in thetwenty-first century:This Institution supports the Constitution of the United States,its Bill of Rights, and its method of representative government.Both our social and economic systems are based on privateenterprise, from which springs initiative and ingenuity. . . .Ours is a system where the Federal Government shouldundertake no governmental, social, or economic action, exceptwhere local government, or the people, cannot undertake it forthemselves. . . . The overall mission of this Institution is, fromits records, to recall the voice of experience against the makingof war, and by the study of these records and their publicationto recall man’s endeavors to make and preserve peace, and tosustain for America the safeguards of the American way of life.This Institution is not, and must not be, a mere library.But with these purposes as its goal, the Institution itselfmust constantly and dynamically point the road to peace,to personal freedom, and to the safeguards of the Americansystem.By collecting knowledge and generating ideas, the Hoover Institution seeksto improve the human condition with ideas that promote opportunity andprosperity, limit government intrusion into the lives of individuals, andsecure and safeguard peace for all.

HOOVER DIGESTRE SEA R C H OP IN ION ON PUBL I C PO L I CYSum m er 2 02 1 HOOV ER DI G E ST.O R GTHE HOOVER INSTITUTIONS TA N F O R D U N I V E R S I T Y

HOOVER DIGESTR ESE A RC H O P IN ION ON P U B LIC P OLICYS um mer 2021 HOOV ER D IG E ST.O R GThe Hoover Digest explores politics, economics, and history, guided by thescholars and researchers of the Hoover Institution, the public policy researchcenter at Stanford University.The opinions expressed in the Hoover Digest are those of the authors anddo not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Hoover Institution, StanfordUniversity, or their supporters. As a journal for the work of the scholars andresearchers affiliated with the Hoover Institution, the Hoover Digest does notaccept unsolicited manuscripts.The Hoover Digest (ISSN 1088-5161) is published quarterly by the HooverInstitution on War, Revolution and Peace, 434 Galvez Mall, Stanford University,Stanford CA 94305-6003. Periodicals Postage Paid at Palo Alto CA andadditional mailing offices.POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Hoover Digest, Hoover Press,434 Galvez Mall, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305-6003. 2021 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior UniversityCONTACT INFORMATIONSUBSCRIPTION INFORMATIONComments and suggestions:digesteditor@stanford.edu 30 a year to US and Canada(international rates higher).(650) 723-1471http://hvr.co/subscribeReprints:Phone: (877) 705-1878(toll free in US, Canada)or (773) 753-3347 (international)hooverpress@stanford.edu(650) 723-3373Write: Hoover Digest,Subscription Fulfillment,PO Box 37005, Chicago, IL 60637ON THE COVERHOOVERDIGESTPETER ROBINSONEditorCHARLES LINDSEYExecutive EditorBARBARA ARELLANOSenior Publications Manager,Hoover Institution PressHOOVERINSTITUTIONTHOMAS F. STEPHENSONChair, Board of OverseersSUSAN R. McCAWVice Chair, Board of OverseersCONDOLEEZZA RICETad and Dianne Taube DirectorERIC WAKINDeputy Director,Robert H. Malott Directorof Library & ArchivesSENIOR ASSOCIATEDIRECTORSCHRISTOPHER S. DAUERKAREN WEISS MULDERJulie Helen Heyneman, a daughter ofSan Francisco, sailed for Europe in 1891to immerse herself in art. Heynemanwould live a full life in pursuit of herpassion—as painter, teacher, andwriter—but for a brief period duringthe terrible Great War, she also shoneas a humanitarian. In 1916, a world awayfrom San Francisco, she founded a placein London called California House as arefuge for disabled Belgian soldiers. Herexample helped the public understand—and prepare for—the needs of woundedwarriors. See story, Page 224.DANIEL P. KESSLERDirector of ResearchASSOCIATEDIRECTORSDENISE ELSONSHANA FARLEYJEFFREY M. JONESCOLIN STEWARTERYN WITCHER TILLMAN(Bechtel Director of Public Affairs)ASSISTANTDIRECTORSVISIT HOOVER INSTITUTION ONLINE www.hoover.orgKELLY DORANSARA MYERSSHANNON YORKFOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIADOWNLOAD OUR M https://instagram.com/hooverinstitutionStay up to date on the latestanalysis, commentary, and newsfrom the Hoover Institution.Find daily articles, op-eds, blogs,audio, and video in one app.TWITTERFACEBOOK

Summer 2021HOOV ER D IG E STDE M O C RACY A ND HUMAN RI GHTS9The Twilight of Human Rights?Today’s deepest challenge to the values of the West comesfrom China, which is moving to sweep away the very idea ofindividual rights. By Charles Hill15Charles Hill: Grand StrategistThe late Hoover fellow was a genius at weaving “giant ideas”into analyses of the problems, and the promise, of the world.By Harrison Smith19Exposing the KleptocratsTen steps to combat the mega-corruption that saps nationalwealth and smothers democracy. By Larry Diamond27Courage, not CancellationFree speech means citizens are willing both to question and tobe questioned. By Peter BerkowitzT HE ECONOM Y32We Are the BuildersPoliticians will not “build back better” with yet more vastpackages of ineffective centralized programs. They must learnwhat communities want and need—and let them fulfill thosewants and needs. By Raghuram G. RajanH O O V ER D IG E ST S u m m e r 20213

37The Shape of RecoveryThe second half of this year is likely to bring a surge in pentup demand, especially in high-value service industries. ByMichael Spence41Borrowed TimeThe United States was already on a dangerous debt bingeeven before the pandemic. More reckless spending willoverwhelm investment, growth, and job creation. By George P.Shultz, John F. Cogan, and John B. Taylor47How to Kill OpportunityThere’s no doubt: the minimum wage deprives low-skilledworkers—especially young people—of an essential foothold onthe job market. By David R. HendersonC H IN A53The High RoadThe US-China rivalry represents, above all, a difference invalues. The United States’ strength springs from its supportfor an open, multilateral world order. By Elizabeth Economy64Better FootingHow to grapple with Chinese ambitions—military, economic,and ideological. By H. R. McMaster4H O O VER DI GE ST Summer 2021

72Taiwan as TriggerAmerican presidents come and go, but Beijing has never oncetaken its eyes off Taiwan, or ceased demanding it. By NiallFerguson85Freedom’s StruggleWith China increasingly dominant, nations in the Indo-Pacificseek their own paths between socialism and capitalism. ByMichael R. AuslinA F R ICA94Ethiopia UnravelsFresh conflict in the Horn of Africa is more than ahumanitarian crisis—it’s a blow to regional security and USinterests. By Jendayi Frazer and Judd DevermontT HE M IDDL E E AST98Studying War No MoreThe Abraham Accords established at least a nascent ArabIsraeli amity. Now educational programs can nurture it. ByPeter BerkowitzN UC L E A R P ROL IFE RAT ION103George Shultz’s VisionThe late statesman dreamed of eliminating the danger ofnuclear weapons. His allies continue striving to make thatdream a reality. By William J. Perry, Henry A. Kissinger,and Sam NunnIM M IGRAT ION108Getting It RightThe push for open borders ignores the hard questions. How toask—and answer—them. By Richard A. EpsteinH O O V ER D IG E ST S u m m e r 20215

113Predators and PreyRising sexual violence in Europe—linked to young immigrantmen—threatens women’s hard-earned rights. It must not beignored. By Ayaan Hirsi AliE DUCAT I ON120How Schools Can Turn the PageAt a time of countless programs for reform, Clint Bolickand Kate J. Hardiman champion reforms that will work. ByJonathan Movroydis128A Republic, if You Can Teach ItA new effort to teach civics education holds real promise—ifour hoary K–12 system can be persuaded to try it. By ChesterE. Finn Jr.N AT IO N AL SEC UR IT Y131This Is No Time to StumbleThe Biden administration gets no honeymoon fromgeopolitical dangers. By Victor Davis HansonCA L IF ORNIA138Tarnished GoldYesterday’s state of limitless promise is today’s state of smokeand mirrors—and broken promises. By Peter Robinson6H O O VER DI GE ST Summer 2021

N AT IV E A M E R ICA NS146Hope and Change in Indian Country?President Biden’s new interior secretary, Deb Haaland, has achance to fix the system that leaves many of America’s firstpeople poor and powerless. But will she take it? By Terry L.AndersonIN T E RVIE WS153The Road to SelfdomTo Matthew Crawford, author of Why We Drive, the openroad symbolizes the vanishing realm of human autonomy andskill. By Russ Roberts164The Man Who Wouldn’t Be CanceledThe mob came for Laurence Fox, a brilliant British actor,after he made some mildly controversial remarks on the BBC.Refusing to apologize and vanish, Fox then launched a quixoticcounterattack: a campaign for mayor of London. By PeterRobinson175“Turning People into Americans”Hoover fellow Niall Ferguson is optimistic that futureimmigrants will find their “kaleidoscopic identity” withinthe American experiment, just as so many others have done.Including him. By Chris Walsh and William McKenzie182“Pluralism Is the Lifeblood”How do healthy democracies embrace both differencesand common values? Hoover fellow Timothy Garton Ashdiscusses the crucial balance—and the danger that lies “downthe road of identity politics.” By Chris Walsh and WilliamMcKenzieH O O V ER D IG E ST S u m m e r 20217

VA LU E S191Small KindnessesLooking back on a year of great tumult and, at times,reassurance. By Condoleezza RiceHISTORY A ND C ULT URE193Disruptive StrategiesA new military-history book edited by Hoover fellow DavidL. Berkey explores the repeated collisions of rising andestablished powers. By Jonathan MovroydisHOOV E R A R C HIVE S201Operation TagilThe Paris archive of the imperial Russian secret police isamong Hoover’s most treasured holdings. How it landed onthe Stanford campus is a cloak-and-dagger tale worthy of thecollection. By Bertrand M. Patenaude219Return to ChernobylThirty-five years ago, a nuclear disaster unfolded in Ukraine.The Soviet empire, too, was about to melt down. Archivalmaterials illuminate those times of danger and dissolution.By Anatol Shmelev2248On the CoverH O O VER DI GE ST Summer 2021

D E MO CRACY A N D H UM A N R I G H TSDEMOCRACY AND HUMAN R IG H TSThe Twilight ofHuman Rights?Today’s deepest challenge to the values of theWest comes from China, which is moving to sweepaway the very idea of individual rights.By Charles HillThe idea of “human rights” is modern. Humanity’s history onlyrecently has recognized the need for such a category, and aconcomitant need to explain what the category covers and whereit comes from.Through most of the twentieth century, and now in the twenty-first to aconsiderable extent, there has been a structural dichotomy between tworegimes: the largely autocratic kind, which declare human rights to be material in content: food, clothing, and shelter; and open societies which, whileagreeing to material needs, have given most political weight to ideals offreedom and justice. All through the Cold War decades the centralized, oneparty regimes of “the East” stressed material necessities while “the West”valorized political considerations. That dichotomy no longer prevails, but theconcept and its practices as actually carried out have shown “human rights”as continuing to evolve ever more into “an American thing.”Charles Hill (1936–2021) was a research fellow at the Hoover Institution andco-chair of Hoover’s Herbert and Jane Dwight Working Group on the Middle Eastand the Islamic World. He was a longtime lecturer in International Studies at YaleUniversity and Yale’s Brady-Johnson Distinguished Fellow in Grand Strategy.H O O V ER D IG E ST S u m m e r 20219

The United States has become the heir, the manager, and the defender ofhuman rights as a global imperative. The modern history of the idea and itsimplementation has followed a winding path, but its major milestones can belocated over the past four hundred to five hundred years as marking the roadto a project, or pillar, of world order in the most consequential sense. Thesemight reveal, significantly yet sparingly, a trajectory of global-scale changeincreasingly moving toward an American-defined contribution to universalbetterment for all nations and people.Among these achievements would be the Mayflower Compact of 1620;Roger Williams’s Rhode Island idea of liberty of conscience; New England’sperception of a “natural law” for man created in God’s image and thereforeprior to and above the state; and Jonathan Edwards’s 1741 sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” which would be interpreted as thefoundation stone for each individual’s decisions on the greatest issues of thehuman condition—a turning point later referred to as “the first AmericanRevolution.”When colonial New England congregational meeting houses began toevolve into town meeting halls, a new political consciousness began to takehold. By a process which today might be called “reverse engineering” it couldbe argued that if a) an individual person was God-created, then b) all personsin at least one important sense must be regarded as equal. Equality wouldrequire a political system of democracy, which in return would be legitimizedtheologically. This inevitable circularity produced an awareness that in aworld of irrefutable diversity the only irreducible basis for equality would be“the soul.” No two people could ever be considered “equal” except in the recognition that every soul had to be equal to all other souls. Here, as in otherdimensions of political life, a theological concept can be located as the originof a later political imperative.This, in an “obvious” extrapolation, would be transformed into the doctrineof “the equality of the states” (as the former United Nations secretary-generalBoutros Boutros Ghali would repeatedly affirm, “a profound doctrine”). Aswith individuals, so also with states: an undeniable differentiation of each “toall” of the collective would be, in judicial terms, overridden by the need tomake everyone, in some sense, equal.HOW STATES FIT INMuch of the modern history of the international diplomatic system can beexplained as a self-organizing effort to gain acceptance of a fundamentalduality: that each state is a basic and individual unit of world affairs, yet10H O O VER DI GE ST Summer 2021

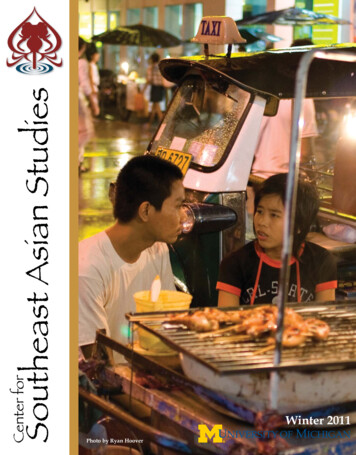

WHICH FUTURE? Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian leader VladimirPutin tour the Kremlin. Human rights, from Beijing’s point of view, are alienand unsuited for present and future times. [Russian Presidential Press and Information Office]that taken together, all states in the international system are conceivedin some sense as universal. Thus we accept “the universality of humanrights.” The simplicity of this recognition is founded upon a complexintellectual and political accommodation. The achievement of this processacross the past two or more centuries should be regarded with admiration by all decision makers of the world order. To put it more directly, theessence of human rights is to be found in the universality of that conceptand its actualization, and universality itself is a quality that must be studied, understood, and strengthened. The international state system and theworld order which is its product is comprised of a complex of structuresand ideas which must be understood and administered as a coherenttotality.H O O V ER D IG E ST S u m m e r 202111

Human rights have been recognized at least semi-formally and partiallyin established international system agreements. The 1973 Conference onSecurity and Cooperation in Europe—CSCE—in Geneva, led to the Helsinki Accords of 1975, abitter political struggleChina is convinced of the superiority ofthat was complicatedand fraught by linkits one-party regime and of the West’sing the acceptance ofinevitable loss of world leadership.concepts of freedomof thought, of conscience, and of religion to a parallel diplomatic recognition of Soviet influence in accordance with what Moscow regarded as thenational borders of Eastern European countries, all of which were in theUSSR’s “sphere of influence.”In the same context, and under the United Nations Charter charge to theUN organization to promote and encourage respect “for human rights andfor fundamental freedom for all,” the UN Human Rights Council’s neglectand mismanagement of these responsibilities led the United States to withdraw from the council in 2018, citing its failure to produce reforms and tooppose human rights abusers discriminating against Israel. As the American ambassador to the council, Kelly Craft, stated, the council had become“a haven for despots and dictators, hostile to Israel, and ineffectual on thehuman rights crises.”DEFINING RIGHTSThe definition of human rights in our time has somehow been understood orassumed, yet never quite clearly spelled out. The example of Hannah Arendtis more than relevant to the need for clarification and simplicity, as herthoughts, decisions, and commitments go to the heart of the matter. Arendtleft Germany and Europe for the United States to escape the impendingNazi movement toward further genocidal actions. Two critical concepts areexemplified by her career as a political philosopher and intellectual model:her condition as “stateless” and her perception of “the banality of evil.”Through the experience of her own years as a stateless person, Arendtunderstood the necessity for a state entity that would declare and defendthe equality of all its people. The logic that would follow would then requirean open political system, that is, democracy, that would give each person anequal voting right. And in turn, this would create an imperative for a free,responsible, and open legal system—the “rule of law”—for law enforcementand judicial administration.12H O O VER DI GE ST Summer 2021

There then appears, almost as a matter of course, a “ladder” of politicallyrecognized and/or politically active categories: from the soul to the personto the state to a national or ethnic culture giving political power beyond thestate to a larger entity, e.g., the Uighur Autonomous Region, to an even largeryet coherent collective such as Tibet or Mongolia.This achievement must be assessed anew as individual states may beobserved as gathering—for various reasons—into “spheres of influence.”There is a China sphere, a Russia sphere, an India sphere, an Iran sphere,and in various forms a Japan, Saudi, and other such spheres. This emergenceof a sphere-of-influence era is, as they say in Silicon Valley, very nontrivial, astwo differing developments are coming into effect and must be neutralized ormanaged.The first development is that although there is a doctrine of “the equalityof states,” there is no doctrine to recognize an equality of spheres. A second,related, development is that the international state system’s concept ofuniversality will not automatically attach itself to an “age of spheres of influence”—yet these two attributes, equality and universality, will be indispensable to the successful working of the world order as we know it now.With such diversity, can there be anything approaching universal rights?Yes, if the internationalsignificance given toCSCE and the HelsinkiThe United States has become theAccords is recognizedheir, the manager, and the defender offor the forward-lookinghuman rights as a global imperative.measures originallyattached to them. The specific language will be contested, but it can be legitimate to claim legitimacy for a short lineup of universal rights on the foundation stones of freedom of speech, of assembly, of religion, of conscience,and of political action within a nation-state system of the rule of law—allunderstood to be available to “the people” under reasonable conditions andrequirements. This amounts to the first ever achievement of a true worldorder of universal reach.IRRECONCILABLE DIFFERENCESThus we arrive at a turning point in contemporary history. From PresidentXi Jinping’s “thought” and other Chinese documents, it is clear that leadersof the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are convinced of the superiority oftheir one-party regime and of the West’s and America’s decline and inevitable loss of world leadership. China in nearly every dimension is preparedH O O V ER D IG E ST S u m m e r 202113

or preparing to supplant the United States in the pre-eminent role. This, inBeijing’s terms, is a certainty and already well under way.The US State Department has officially described the world situation:Awareness has been growing in the US—and in nations aroundthe world—that the Chinese Communist Party has triggered anew era of great-power competition. . . . American statecraftdepends on grasping the mounting challenge that the PRC posesto free and sovereign nation-states and to the free, open, andrules-based international order that is essential to their security,stability, and prosperity.Official PRC documents have described the present situation in hundredyear terms, beginning with the formation of the Chinese Communist Party inthe May Fourth Movement (1917–21). This, in PRC terminology, is an “objective” reality that is now coming to fruition and will end the era of “White”Western dominance of the international state system.The key to this global transformation will turn on “universal” humanrights. These, from Beijing’s point of view, are alien and unsuited for presentand future times. Xi Jinping’s “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics,” thatis, a world led by autocratic, undemocratic regimes, is said to be the wave ofthe future, a wave about to break on the shores of the West.This contest already has begun in the matter of human rights: are they“Western,” or are they truly universal in some fundamental way?Subscribe to The Caravan, the online Hoover Institution journal thatexplores the contemporary dilemmas of the greater Middle East (www.hoover.org/publications/caravan). 2021 The Board of Trustees of theLeland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.Available from the Hoover Institution Press is Russiaand Its Islamic World: From the Mongol Conquest tothe Syrian Military Intervention, by Robert Service. Toorder, call (800) 888-4741 or visit www.hooverpress.org.14H O O VER DI GE ST Summer 2021

D E MO CRACY A N D H UM A N R I G H TSDEMOCRACY AND HUMAN R IG H TSCharles Hill:Grand StrategistThe late Hoover fellow was a genius at weaving“giant ideas” into analyses of the problems, andthe promise, of the world.By Harrison SmithHoover research fellow Charles Hill, a Cold War diplomat whoadvised two secretaries of state and the head of the UnitedNations before reinventing himself as a university professor,founding Yale’s influential Grand Strategy program to connecthistory and literature to the study of statecraft, died March 27 at a hospitalin New Haven, Connecticut. He was 84.Laconic and soft-spoken, Hill spent nearly his entire government careerworking behind the scenes, avoiding photo ops while serving as a speechwriter and aide to secretaries of state Henry Kissinger and George P. Shultz. Hewas later a policy consultant to Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the secretary-generalof the United Nations, during a tumultuous period in the 1990s that includedthe breakup of Yugoslavia, genocide in Rwanda and civil war in Somalia.“Attention isn’t something that’s very interesting to me. It seems to use alot of time that could be spent on something else,” he told the Hartford Courant in 2006. “Ronald Reagan had a plaque on his desk which read, ‘There’sno limit to what you accomplish, as long as you don’t care who gets thecredit.’ ”Harrison Smith is an obituary writer for the Washington Post.H O O V ER D IG E ST S u m m e r 202115

A self-described “Edmund Burke conservative,” Hill championed whathe described as the liberal world order, arguing in recent years thatIslamism posed a global threat and that the United States “has to stand fordemocracy.”Hill started out in the Foreign Service, with postings in Europe, East Asia,and South Vietnam, where he was a speechwriter for Ambassador EllsworthBunker. He later advised Bunker on the Panama Canal treaty negotiationsand, in 1974, began working for Kissinger as a speechwriter.“He reviewed almost everything I wrote,” Kissinger said in a phone interview. “What made him effective was his thoughtfulness, his unselfishness, hisdedication to ideas, his understanding of human beings.” Hill, he added, possessed an “acute judgment” on issues ranging from the evolution of China tothe Arab-Israeli conflict, which he increasingly focused on during the Carteradministration.Hill served as political counselor for the US Embassy in Tel Aviv, directorof Arab-Israeli affairs, and deputy assistant secretary of state for the MiddleEast. In 1985, he was named executive aide to George Shultz, a post thatmade him chief of staff to Reagan’s top diplomat during a period that included nuclear weapons negotiations with the Soviet Union and efforts to start adialogue with Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.In part, “his influence lay in his quite extraordinary, relentless note-taking,”said his former student Molly Worthen, author of The Man on Whom NothingWas Lost, a 2006 biography of Hill. He producedabout twenty thousand“The international world of statespages of notes—chroniand their modern system is a literarycling everything from arealm.”religious ceremony in Fijito comments that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s wife, Raisa, made at dinner—resulting in documents that shaped policy discussions.“I don’t think there was anyone that Shultz trusted more,” Worthen said.After George H. W. Bush took office as president, Hill resigned fromthe Foreign Service and helped Shultz write his 1993 memoir, Turmoil andTriumph. Three years later he began teaching full-time at Yale, where he wasbest known for Studies in Grand Strategy, a yearlong course he created in2000 with historians John Lewis Gaddis and Paul Kennedy. Loosely modeledafter a class at the Naval War College in Rhode Island, the course examinedlarge-scale issues of statecraft and social change while drawing on classicworks of history and literature.16H O O VER DI GE ST Summer 2021

WORLDLY WISE: Charles Hill’s class was a forum “to talk about giant ideasand not simply make foreign affairs a matter for the technocrats.” [Eric Dietrich—US Navy]“The international world of states and their modern system is a literaryrealm; it is where the greatest issues of the human condition are playedout,” he wrote in a 2010 book, Grand Strategies: Literature, Statecraft,and World Order, which examined the development of the modern statewith help from works by Homer, Thucydides, Franz Kafka, and SalmanRushdie.Hill came to embody the Grand Strategy course, which was credited withinspiring similar classes at schools including Duke and the University ofTexas. Addressing students by their last names, holding open-door officehours each week, Hill developed a devoted following among undergraduates.“Charlie’s criticism of the Clinton administration was always that it wasa bunch of very, very smart wonks who can’t see the forest for the trees,”Worthen said. Hill and his colleagues “were reasserting the need to talkabout giant ideas and not simply make foreign affairs a matter for theH O O V ER D IG E S T S u m m er 202117

technocrats,” Worthen said. “And then 9/11 happened. I was an undergraduate then, and we were so hungry for someone to explain it to us.”Morton Charles Hill was born in Bridgeton, New Jersey, on April 28, 1936.His father was a dentist, his mother a homemaker. He received a bachelor’sdegree from BrownUniversity in 1957 andstudied at the University“I don’t think there was anyone thatof Pennsylvania, whereShultz trusted more.”he graduated from lawschool in 1960 and earned a master’s degree in American studies in 1961,shortly before joining the Foreign Service.In an interview, his colleague Gaddis said Hill focused on literature evenmore than his Grand Strategy partners, believing that great books offered “akind of inner vision of how people’s emotions or minds are working.”“Yale administrators didn’t know what to do with him, where to put him,”Gaddis added. “He existed outside of departmental structures. More significantly, he existed outside of specialties. I would say his specialty was findinglinkages between specialties. It’s the opposite of siloing, looking for connections across disciplinary boundaries. And of course, there is almost nobodyelse around at Yale who does that now.”Reprinted by permission of the Washington Post. 2021 Washington PostCo. All rights reserved.Available from the Hoover Institution Press is TheWeaver’s Lost Art, by Charles Hill. To order, call (800)888-4741 or visit www.hooverpress.org.18H O O VER DI GE ST Summer 2021

D E MO C

The Hoover Digest explores politics, economics, and history, guided by the scholars and researchers of the Hoover Institution, the public policy research center at Stanford University. The opinions expressed in the Hoover Digest are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Hoover Institution, Stanford