Transcription

OL15COMMUNICATIONAPPREHENSION OFELEMENTARY ANDSECONDARY STUDENTSAND TEACHERSOver the past decade, a substantialamount of research literature has developed concerning oral communicationapprehension(CA). Most of the empirical work in this area has focused onthe correlates, effects, and treatments forCA.l However, causal explanations forthe development of CA have receivedmuch less attention.The most commonly employed theoretical explanation of CA developmenthas been framed within a reinforcementparadigm.:! As :\IcCroskey has suggested,"If a child is reinforced for being silentand is not reinforced for comumunieating, the probable result is a quietchild. In addition, if the child not onlyis not reinforced for communicatingbut often experiences some aversive experience (parent shouting, big brotherhitting)when attemptingto communicate, the quiet child result is evenJames C. McCroskey is Professor and Chairp rs n: Janis .F. AndeT:en is ssistant Professor,Virginia P. Richmond IS Associate Professor. andLawrence R. Wheeless is Professor and Assodate Ch3:irp rson of the Depa u ent of. Spe hCommunIcation,WestVlrgtnIaUnIversity.Morgantown, WV 26506.l For a summary of this research. see James . McCroskey. "Oral Communication ApprehenSlOn: A Summary of Recent Theory and Research," HumanCommunicationResearch, 4(Fall 1977). 78.96.:! See. for example. William K. Ickes. "AClassical ConditioningModel for 'Reticence:"Western Speech. 35 (Winter 1971). 48-55; JohnA. Daly and Gustav W. Friedrich. "The Development of CommunicationApprehension:ARetrospectiveAnalysis of Some ContributoryCorrelates,"' Paper presented at the annual SCAcon\'cntion, Iil1ne:J.polis, 1978: and McCroskey.COM:\IC\'ICATIONEDt:CATION.James C. McCroskeyJanis F. AndersenVirginia P. RichmondLawrence R. Wheelessmore probable."3 Evidence from casestudy analyses,4 research on CA treatment,a and research on social anxiety8has clearly supported such a reinforcement explanation.No other potentially causal mechanismin the development of CA has receivedmore than limited empirical validation,although potential hereditary influenceon CA development has received someattention. After reviewing the literatureon infant sociability, social apprehension, and physical attractiveness, Dalyconcluded that genetic factors may influence the developmentof CA.7 Inextendingthis possible relationship,Andersen and Singleton found bodytype (which is primarilygeneticallydetermined) to predict CA in women.sWhile hereditary factors must be considered a possible contributing elementin CA development,even ardentproponents of social biology stress the3 McCroskey. p. 80.4 Gerald M. Phillips. "Reticence: Pathologyof the Normal Speaker," Speech Monographs,35 (March 1968). 39-49.IiJames C, McCroskey. "The Implementationof a Large.Scale Program of Systematic Desensitization for CommunicationApprehension."Speech Teacher, 21 (Nov. 1972). 255.64.8 See. for example. John A. Daly, "The Developmentof Social-CommunicativeAnxiety,"Paper presented at the annual convention of theICA. Berlin. West Germany. 1977; and Dalyand Friedrich.7 Daly.8 Petcr A. Andersen and George W. Singleton.'"The Relationshipbetween Body Type andCommunicationAvoidance," Paper presented atthe annual convention of the Eastern Communication Assn., Boston. 1978.Volume 30. April1981

COMMUNICATIONenvironment in altering genetically determined predispositions. We are left,then,withsomeindicationthathereditary elements may contribute toCA development but with most availabledata that points toward reinforcementpatterns as the primary causal agent.Evidenceon reinforcementas acausal force in communication apprehension suggests two potentially influentialenvironments, the home and the school.Research by Giffin and Heider providesevidence that early experiences in thehome environment explain adult anxiety.!) Other developmentalliteraturesupportsthis position.IoDaly andFriedrich note research findings whichpoint to differences in the home environment, such as amount of familytalk and style of parent-childinteraction,as predictiveof children'scommunication behaviors. Furthermore,they found that college students' recollections of early experiences in the homeenvironmentwere predictive of communicationapprehension.llRandolphand i\JcCroskey advanced a theory offamily size (based upon presumed differentialreinforcementpatterns)topredict communicationapprehension.Early results were promising,butreplication with a larger sample failedto demonstrate a relationship betweenfamily size and communicationapprehension.I2 McCroskey and Richmond!) Kim Giffin and M. Heider, "The Relationship between Speech Anxiety and the Suppressionof Communicationin Childhood,"Psychiatric Quarterly Supplement, part 2 (1967),311-22.10 See, for e."Cample, D. ThomasPorter,"CommunicationApprehensionCausation: Toward an Empirical Answer," Paper presented atthe annual meeting of the ICA, Chicago, 1978.11 Dalv and Friedrich.12 Fred L. Randolphand James C. McCroskey, "Oral CommunicaticnApprehensionAs a Function of Familv Size: A PreliminaryInvestigation,"Paper presented at the annualconventionof the EasternCommunicationAssn., New York, 1977; idem., "The Cause(s) ofOral CommunicationApprehension:Failure ofa Theory," Paper presented :n the annual con-APPREHENSION-I23found that children from families inrural environments were more likely tobe highly communicationapprehensive.13The school envionment has also beendiscussed as a causal .force in the development of communication apprehension. Phillips' analysis of case studiesof reticent individuals points to the firstfew years of school as importantto the development of communicationreticence.14 Also employing case studies,Davey found a large number of highreticents in the early grade schoolyears.15 Daly and Friedrich found thatcollege students' recollections of gradeschool environments were predictive ofcurrentapprehension.16Furthermore,Porter found recollectionsof earlyschool experiences to be more relevantto communicationapprehensiondevelopment than recollections of preschool home experiences. IT He citesdevelopmentaltheories which supportthe important influence of the schoolenvironment on child personality andsocial ONOFThe primary purpose of the present research was to provide a basis for subsequent research probing the schoolenvironmentas a potential cause ofincreased communication apprehensionvention of the Eastern CommunicationAssn.,Boston, 1978.13 JamesC. McCroskeyand VirginiaP:Richmond, "Community Size As a Predictor ofDevelopment of CommunicationApprehension:Replicationand E."Ctension," CommunicationEducation, 27 (Sept. 1978), 212-19.14 Phillips.15 William G. Davey, "CommunicationPerformanceand Reticence: A Diagnostic CaseStudy in the ElementaryClassroom."Paperpresentedto the annual conventionof the\Vestern Speech CommunicationAssn., Seattle.1975.16 Daly and Friedrich.17 Porter.

124-COMMUNICATIONEDUCATIONin some children. Preliminary interviewswith elementary school teachers clearlyindicatedthat such teachers couldrecognize widely differing levels ofcommunicationapprehensionamongyoung children, even at the point whenthey first enter the school environment.This information suggests at least twopossibilities:(1) Communicationapprehension levels are well establishedbefore entering the school environment.Thus, previous research which hasidentifiedcorrelationsbetween communication apprehension and recalledschool experiencesmay infer falsecausation-the communication apprehension may generate either the experienceor the memory of the experience, forexample. (2) Communication apprehension levels are only weakly establishedbefore entering the school environmentand, thus, are subject to substantialmodification (either higher or lower) asa result of school experiences.No extended longitudinalresearchon communication apprehension amongchildren has been reported. Were suchdata available, at least one of the abovepossibilities could be ruled out. Eitherthe communicationapprehension levelremainsrelativelyconstantthroughchildhood and into adulthoodor itdoesn't. Unfortunately, we do not knowthe answer to this question. Only substantiallongitudinalreseachcan providea definitive answer. Anecdotal evidence,however, is suggestive of a possibleanswer. Numerous, but unsystematic,discussions with college and adult students, who have been exposed to theliterature on communication apprehension, have resulted in many commentsto the effect that "I used to be a highcommunication apprehensive, but I amnot anymore." Interestingly,oppositestatements have been totally absent,perhaps because no one ever becomesmore apprehensive, or because peoplewho are now high apprehensives, butwere not previously, prefer to keep thatinformation to themselves.The anecdotal evidence, then, suggeststhe possibility that communication apprehension levels can change, at least inone direction-down.Hard data, however, suggest that normative communication apprehensionlevels in largesamples of college freshmen,otheradults, and even senior citizens areessentially the same.1S Unfortunately, nocomparable normative data for largesamples of younger children are yetavailable. One of the purposes of thepresent research, therefore, was to generate such normative data for school-agechildren, K-12.Because of the limited research oncommunicationapprehensionamongyoung children, formulation of a priorihypotheses was difficult. The only previous research which was suggestive wasdirected toward speech fright ratherthan communication apprehension. Thisresearchemployedobserver ratings,introspectivetests, and physiologicalmeasures (GSR). The results indicateda substantial increase in speech fright between third graders and sixth graders.19On this tenuous base, the followinghypothesis was advanced:H1: Mean communicationapprehensionscoresof children in grades K-3 are lower thanmean communicationapprehensionscoresof children in grades 4-6. 7-9, and 10-12.18 See, for example,James C. McCroskey,"Measures of Communication-BoundAnxiety,"Speech Monographs, 37 (1970). 269-77; DennisL. Moore, "The Effects of Systematic Desensitization on CommunicationApprehensionin anAged Population,"Thesis Illinois State Univ.1972; and RaymondL. Falcione, James C.McCroskey, and John A. Daly. "Job SatisfactionAs a Function of Employees' CommunicationApprehension,Self-Esteem. and Perceptions ofTheir ImmediateSupervisor," in Communication Yearbook I, ed. Brent D. Ruben(NewBrunswick, N.J.: Transaction.1977), 363-76.19 For a summarvof this research,seeLawrence R. Wheeless, "CommunicationApprehension in the Elementary School," SpeechTeacher, 20 (Nov. 1971), 297-99.

COMMUNICATIONINSTRUMENTDEVELOPMENTThe primary instrument for measuringCA in previous research is the PersonalReport of CommunicationApprehension (PRCA). This instrument has beendemonstrated to be both reliable andvalid.2O However, the PRCA was developed for, and has been used almostexclusively for, measuring the CA ofhigh school students and adults. Thelanguage level of the PRCA limits itsuse with young children. Thus, thePRCA could not be used with confidencefor all of our student samples.Recently, ,a measure designed to beadministeredto preliteratechildrenhas been reported. This instrument, theMeasure of Elementary CommunicationApprehension(MECA), is framed inlanguage appropriate for younger children and uses various forms of smilingand frowning faces for response options.21 This instrument was consideredappropriatefor our younger studentsamples, but, because of the responseformat, the measure was not consideredappropriate for junior and senior highschool student samples.As a result, a preliminary study wasdesigned to develop a measure of CAthat could be administered to all elementary and secondary school students,regardless of age level. Twenty itemswere written at a level believed to beunderstandablefor childrenin thepreliterate stage of development as wellas older students. The instrument wasadministered orally to children belowseventh grade level. For the responseformat employed, see Table 1. The20 IcCroskey, "Measures of Communication.Bound Anxietv"; and idem. "Validity of .thePRCA As an' Index of Oral ,45 (Aug. 1978). 192-203.::1 Karen R. Garrison and John P. Garrison.":\Icasurement of Communication. pprehensionamongChildren:'Paperpresentedat theannual cOlI\'ention of the ICA. Berlin. 'VestGermanv, 1977.APPREHENSION-l25instrument was administeredto 2,228students in five school districts. Thesample included the following numbersof subjects at the various grade levels:K-3, 248; 4-6, 462; 7-9, 762; and 10-12,756. The instrumentwas also ad.ministered to 875 college students.The data for each of the five subjectgroups were submitted to factor analysisto determine whether the instrumentwas unidimensional, as presumed initially. The results for each subject groupclearly indicated the presence of two interpretable factors, although the factorswhen subjected to oblique rotation werecorrelated (from .39 to .57, dependingon sample). The first factor could belabeled the "fear or anxiety" dimension,the second the "shyness or verbosity"dimension. Fourteen of the items hadtheir primary loading on the first factor,six were loaded primarily on the secondfactor. Although the magnitude of theloadings varied somewhat among the fivesamples, the general pattern was highlyconsistent.Since this preliminarystudy wasfocused on the development of an instrument(as it turned out, two instruments), reliability and validity wereprimary concerns. The obtainedreliabilities for the two dimensions (splithalf, internalconsistency) for eachgrade-level grouping are reported inTable 3. Although the reliabilities weregenerally within a satisfactory range atall grade levels, it was decided to try toimprove the instrumentsby addingitems. Consequently, an eighteen-itemversion of the "fear" scale and a sixteenitem version of the "shyness" scale wereprepared and administered to 705 college students.Factor analysis withoblique rotation indicated the presenceof the two dimensions, with a correlation of .55 between the dimensions.Four of the items on the "fear" dimension and two on the "shyness" dimension

126-COMMUNICATIONEDUCATIONwere dropped for subsequent use sincetheir loadings split between the factors.The resulting two scales, named thePersonalReportof CommunicationFear (PRCF) and the Shyness Scale (SS),are reported in Tables I and 2. TheTABLE IPERSONALREPORT OF COMMUNICATIONFEA1l (pRCF)DIRECTIOSS:The following 14 statements concern feelings about communicatingwith otherpeople. Please indicate the degree to which each statement applies to you by circling yourresponse. Mark "YES" if you strongly agree, "yes" if you agree, "?" if you are unsure, "no" ifyou disagree, or "NO" if you strongly disagree. There are no right or wrong answers. Workquickly; record your first NG:?nonononononononononononononoYES .10.11.12.13.14.Talking with someone new scares me.I ook forward to talking in class.I like standing up and talking to a group of people.I like to talk when the whole class listens.Standing up to talk in front of other people scares me.I like talking to teachers.I am scared to talk to people.I like it when it is my turn to talk in class.I like to talk to new people.When someone asks me a question, it scares me.There are a lot of people I am scared to talk to.I like to talk to people I haven't met before.I like it when I don't have to talk.Talking to teachers scares me. 2. ? 3, no 4,NO 5.To obtain the score for the PRCF, complete the following steps:1. Add the scores for the following items: 2, 3, 4. 6, 8, 9, and 12.2. Add the scores for the following items: 1,5,7, 10,11, 13, and 14.3. Add 42 to the total of step 1.4. Subtract the total of step 2 from the total of step 3.The score should be between 14 and 70.TABLE 2SHYNESSSCALE (SS)DIRECTIOSS:describes yousure whetherthe statementof you, esSCORING:The following 14 statements refer to talking with other people. If the statementvery well, circle "YES." If it somewhat describes you, circle "yes.» If you are notit describes you or not, or if you do not understand the statement, circle "?" Ifis a poor description of you, circle "no," If the statement is a very poor description"NO." There are no right or wrong answers. Work quickly; record your nonoNO1';0NONOYES I,?yesI.2.3".4.5.c.i.R.9.10.I am a shy person.Other people think I talk a lot.I am a very talkative person.Other people think I am shy.I talk a lot.I tnd to be very quiet in class.I don't talk much.I talk more than most people.I am a quiet person.I talk more in a small group (3.6 people)than other people do.II. Most people talk more than I do.12. Other people think I am very quiet.13. I talk more in class than most people do.14. Most people are more shy than I am. 2, ? 3, no 4, NO 5.To obtain the score for the SS. complete the following steps:1. Add the scores for the following items: 2, 3. 5, 8, 10, 13, and 14.2. Add the scores on the following items: 1,4,6,7,9,11,and 12.3. Add 42 to the total of step 2.4. Subtract the total of step I from the total of step 3.The score should be between 14 and 70

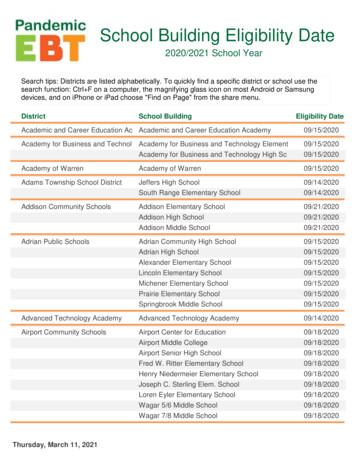

COMMUNICATIONreliabilities obtained for the follow-upcollege sample, reported in Table 3, werein excess of .90 for both scales. Consequently,. these scales were used in thelater study.TABLE 3RELlABILlTIES OF PRCFGrade LevelK-34-67-910-12CollegeCollege(folIow-u.I1AND 55 INSTRUMENTSAdministrationPreliminaryStudiesMain .92.70.79.84.90.82.86.90.92To assess validity of the new instrument (ultimately two instruments), theK-3 and 4-6 samples in the preliminarystudy were administered the MECA, andall of the samples were administered thePRCA-ShortForm.:!:! Presumingthevalidity of the PRCA and MECA scales,although the case for the latter is yetto be argued empirically, the obtainedcorrelations between the two new scalesand the PRCA/:\IECA provided us withconcurrent validity coefficients for thenew scales. The raw validity coefficientsand disattenuatedcoefficients are reported in Table 4, which indicates thatthe PRCF consistently obtained higher,:!:!For a copy of this form. see McCroskey,"Validity of the PRCA."APPREHEN5ION-127usually very much higher, validity coefficients than the SS. When using thePRCA as the criterion, the PRCF generated very high validity coefficients.Given the cibvious language-level validityproblems with the 'PRCA for preliteratechildren, the coefficient at the K-3 levelwas particularly encouraging.The validity coefficients for the SSsuggest this scale is not measuring CAas well as the PRCF. Rather, it likely istapping communication behavior relatedto CA, but not solely caused by CA.While this type of conceptual distinctionbetween CA and shyness has beenalluded to previously,23 this is the firstempirical indication in the literature.Consequently, it was decided that it wasimportant to include both measures inthe main study of school children, eventhough no hypothesis about shynessoriginally had been proposed.PROCEDURES AND RESULTS:STUDENTS AS SUBJECTSSubjects in this study included 5,795elementary and secondary school students enrolled in sixty-seven school districts in three states. The breakdown bygrade level was as follows: K-3, 1,252;4-6, 1,741; 7-9, 1,752; and 10-12, 1,050.All stUdents were municationAppre-4VALlDITYCOEFFICIENTSFOR PRCF AND55Grade 16.65.284.67-910-12College.Validity .98.49.95.60.84.45

l28-COMMUNICATIONEDUCATIONPRCF and 55 by their regular classroominstructor.For those students undergrade 7, the scales were administeredorally. Obtainedreliabilitiesfor thescales are reported in Table 3. The -datawere submittedto single-classification(four levels) analyses of variance. Obtained means for both scales are reportedin Table 5.TABLE 5MEAN PRCFAND SS SCORES BY GRADE-LEVELGROUPINGScaleGrade 67-910-12a score range 14-70. High score high fear.score range14-70. High scorehighlytalkative. b hypothesis was framed for the 55 scores,the pattern of means on this scale indicates that the younger children aremore verbal (less shy) than their olderpeers. Again the -devial!t group is thechildren in grades K-3.Although the sample sizes are sub.stantially lower, and thus the means lessstable, it is interesting to consider thePRCF scores at each grade level duringthe early years. The means are asfollows: K, 25.8; 1, 33.0; 2, 32.9; 3, 33.0;4, 34.7; and 5, 37.1. Since our subjectscompleted the measures during the firstsemester of their reported grade, eachgrade level presumably reflects impactof the previous year. Notable changesappear to occur during kindergartenand grades 3 and 4. Means from thatpoint on (to and including college) remain virtually identical.The results indicated a significanteffect for grade level on both the PRCFDISCUSSION87.43, P .0001) and the 5Sscores (Fscores (F69.21, P .0001). As noted Although we had little basis for ourin Table 5, the mean PRCF scores were primary hypothesis, the results of theyirtually identical for all grade levels research provide considerable supportexcept K-3. As hypothesized, the scores for that hypothesis. Children in lowerelementary school (K-3) report lowerfor the K-3 group were significantlylower. Note that the hypothetical mean levels of CA than do children in upperof the PRCF scale is 42; thus, the ob- elementary school (4-6), junior hightained differences are not likely to be a school (7-9), or high school (10-12). Thebiggest change appears to occur infunction of lower reliability or validityduring the child's firstfor the younger subjects. Random re- kindergartensponses would cancel themselves out to exposure to the school environment. Anincrease appears toproduce higher rather than lower scores other substantialoccurduringgrades3 and 4. Thus, befor the younger groUp. 4 Although nofore puberty, CA norms are achievedthat remain relatively stable through all -IThis only applies to randoI/! error. Afterreading an earlier draft of this paper. John Dalysubsequentage groups.of the University of Texas raised the possibilityWhilethesenormative data clearlythat there may be a systematic error in .thescores. As he correctly noted, in the typicalindicate that some factor or factors relower-grade classroom there is a great deal ofinieraction,but this tends to be reduced insult in increased CA among childrenhigher grades as classrooms become more strucwhile they are attendingelementarytured with rules regardinginteraction.Dalyschool, they do not establish that anyasks if it is possible that the students completedthe instrument with their primary focus on theelement in the school is the causal agent.classroom in which thev were students. If so, the scores mav simply' reflect their classroomexperiences rather than general dispositions. 'Vecannotcompletelydiscountthis possibility.However, the items on the measures,par-ticularly the Shyness Scale, appear to be sogeneral as to preclude this as the sole explanation of the obtained results.

COMMUNICATION APPREHENSION-129Indeed, biological and/or social maturationalelements unrelatedto theschool may account for all of thisvariation. Nevertheless, until establishedotherwise, we should continue to suspectthe school environment as a potentialcausal agent for increased levels of CAin children.Given that we continue to suspect theschool environment, and given that wemay wish to alter that environment soas to remove any negative influence, ourfocus on the school environment shouldbe narrowed to the factors that have thehighest probabilityof impact, eithernegative or positive. Althoughthenumber of variable elements in theschool environment are nearly limitless,we believe we can narrow our concernto three: (1) the physical facilities, (2)the peer environment,and (3) theteachers.Although school facilities have anobvious relationship to the type of teaching which can occur and to the communication environment of the child,we discounted this factor as a possiblecause of the differences in norms. Ourdata were obtained from schools withvirtually every type of facilities imaginable-old and new buildings, large andsmall buildings, open and traditionalclassrooms, urban and rural schools, andso on. Supplementaryanalyses, whichwere conducted to provide feedback tothe teachers who assisted us in thisproject, gave no indication of any pattern of differential results from schoolto school or area to area. In short, eventhough physical facilities may have amajor impact on classroom communication, they are an inadequate explanationof the differential norms we observed,The impact of peers cannot be discounted. Many children encounter theirfirst real contact with peers when theyenter kindergarten, and this contact mayserve to increase a child's inhibitionsand, hence, the CA level. Future research should compare changes in CAlevel of children who have had littlepeer contact before kindergartenwiththose children who have. Perhaps children with early, extensive peer contactare immunized against developing CA,or they may simply develop CA earlier.In any event, such research can give ussome insight as to whether children's CAis being impacted purely by peer contactor whether some other school-relatedelement is influential.The third element in the school environment, teachers, also is difficult todiscount as a causative factor. Casestudies and other anecdotal evidenceregularly highlight the impact of a giventeacher's behavior on children. At thispoint, unfortunately, we are forced tospeculate as to the types of teacherbehaviors that might lead to highercommunicationapprehensionamongschool children. No direct observationalevidence exists of teachers' behavior withchildren who develop higher or lowerCA. Similarly, some types of teachersmay be more or less likely to increasechildren's CA levels than other types;but, we may only speculate at this pointas to what those types may be.Our extensive experienceworkingwith in-service elementary and secondaryteachers caused us to suspect one elementthat may be a contributing factor to thekinds of normative CA level increasesobserved in the above study. Althoughprevious research has indicatedthatnormative levels of CA among elementary and secondary teachers approximatethose of college student and adultgroups, we have observed that an unusually large number of elementaryteachers have high CA; at the same time,a very low proportionof secondaryteachers have high CA. If, indeed, thereare significant numbers of high CAteachers in the lower elemen tary grades,

l30-COMMUNICATIONEDUCA TIO:\this may provide at least a partial explanation for the increases in children'sCA levels in these grades.Previous research has established thatpeople with high CA communicate lessfrequently and in different ways thanpeople with low CA. Although none ofthis research has involved direct observation of teacher communication behavior, teachers' behavior is as likely tobe impacted by CA as is behavior ofpersons in other occupations. For example, high CA teachers may talk lessin the classroom, thus providing modelsof quietness that could be reinforced ina child's mind. Similarly, the high CAteacher may be more likely to reinforcewithdrawn behavior than would anotherteacher. Thus, if a significantly largerproportion of teachers in lower elementary grades are high CA's than in othergrades, a possible explanation for thedifferential norms we observed wouldcenter on those high CA teachers andtheir behavior in the classroom. On thebasis of these speculations,following hypotheses:we posed theH,: There is a higher proportionof teacherswith high CA in the lower elementarygrades (K.4) than at other grade levels.H.: There is a higher proportionof teacherswith high CA in the lower elementarygrades (K-4) than there are teachers withlow CA in those grades.Hypothesis I is the expectation based onour experience with in-service teachers.If it were not confirmed, our speculationconcerningthe impact of high CAteachers on children obviously would beout of order. If there were the samenumber of high CA teachers at eachlevel, something other than CA level ofteacher would have to account for thechildren's increased CA during the earlyelementary years. Hypothesis 2 also teststhe heart of our speculation. If therewere an equal number of high and lowCA teachers in the elementary schools,their impact on the norms for a largenumber of students would be expectedto cancel each other out. Thus, for ourconcern about the impact of high CAteachers on the development of CA inchildren to be worthy of additionalstudy, both of these hypotheses must beconfirmed.Any other result wouldindicate our concern to be misplaced.PROCEDURE AND RESULTS:TEACHERS AS SUBJECTSThe sample studied included 573 inservice elementary and secondary schoolteachers from fifty-seven school districtsin five states. All of the subjects wereenrolled in graduate instructional communication classes taught in ten separatelocations. Subjects completed the required instruments for the study on thefirst day of class before any discussionof the subject matter.The subjects completed the PRCAShort Form23 and responded' to twoother questions. The first asked them toindicate the grade level at which theytaught, and the second asked them toindicate the grade level at

Speech Monographs, 37 (1970). 269-77; Dennis L. Moore, "The Effects of Systematic Desensitiza-tion on Communication Apprehension in an Aged Population," Thesis Illinois State Univ. 1972; and Raymond L. Falcione, James C. McCroskey, and John A. Daly. "Job Satisfaction As a Function of Employees' Communication Apprehension, Self-Esteem. and .