Transcription

1

2

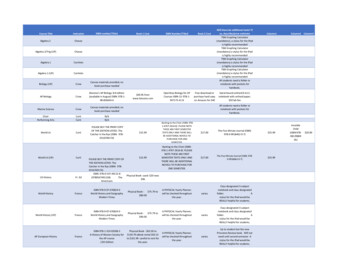

Agência Brasileira do ISBN – Bibliotecária Priscila Pena Machado CRB-7/6971Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP)Agência Brasileira do ISBN – Formato: Livro DigitalVeiculação: DigitalEditora IBCI –São Paulo-SP / Brasília-DF – 2021 – Edição Digitalwww.ibcibr.com.br3

O IBCIO Instituto Brasileiro de Concorrência e Inovação - IBCI - é um think tankaberto e sem fins lucrativos criado em 2012 a partir da iniciativa conjuntade um grupo de Professores da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de SãoPaulo (PUC-SP) e da Universidade de São Paulo (USP). O IBCI pregavalores de livre iniciativa, livre concorrência, inovação, level playing fieldpara a construção de uma sociedade mais justa, com mais bem-estar emenos desigualdade por meio de mercados abertos e competitivos.Fazendo jus aos seus pilares de existência, o IBCI é composto por umquadro multidisciplinar e 100% paritário de diretores e diretoras, isto é,50% mulheres e 50% homens, todos com reconhecido destaque em suasrespectivas áreas de pesquisa, docência e atuação profissional.The IBCIThe Brazilian Institute of Competition and Innovation - IBCI - is an open,non-profit think tank created in 2012 based on the joint initiative of a groupof Professors from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUCSP) and from University of São Paulo (USP). IBCI preaches values of freeinitiative, free competition, innovation, and level playing field to build a morejust society, with more welfare and less inequality through open andcompetitive markets.Living up to its pillars of existence, the IBCI is composed of amultidisciplinary and 100% equal number of directors, that is, 50% womenand 50% men, all with recognized prominence in their respective areas ofresearch and academy.4

Composição do IBCI – 2021Alexandre Naoki NishiokaAluísio de Freitas MieliAna Cristina GomesAndré Santa CruzEduardo Molan GabanFabiola ZibettiFrédéric MartyGiacomo PailiiJuliana Oliveira DominguesLaura ZoboliLuciana YeungMagali EbenMariana MaduroThibault SchrepelVinícius Klein5

Conselho EditorialAlexandre Naoki NishiokaAndré Santa CruzEduardo Molan GabanFabiola ZibettiFrédéric MartyGiacomo PailiiJuliana Oliveira DominguesLaura ZoboliLuciana YeungMagali EbenThibault SchrepelVinícius Klein6

CoordenadoresEduardo Molan Gaban – PhD. in Law from the Pontifical Catholic University ofSão Paulo, Brazil (PUC-SP). Former Visiting Fulbright Scholar at New YorkUniversity School of Law (2010-2011). Non-Governmental Advisor – NGO- atICN, active in the Cartel Working Group. Professor of Economic Law at theUniversity of São Paulo and Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná (both in thepost-graduation programs). Director at the Brazilian Institute for Competition andInnovation – IBCI (www.ibcibr.com.br). Contact: gaban@ibcibr.com.brVinícius Klein – PhD. in Law from the Rio de Janeiro State University, PhD inEconomic Development from Paraná Federal University, Visiting Scholar atColumbia University in 2012, Professor of Law and Economics at Paraná FederalUniversity. Director at the Brazilian Institute for Competition and Innovation – IBCI(www.ibcibr.com.br). Contact: klein@ibcibr.com.brOrganizadoresAna Cristina Gomes – Doutoranda em Direito pela Universidad de Salamanca.Mestre e graduada em Direito pela UNESP. Coordenadora Chefe doDepartamento de Monografias do IBCCrim. Membra da Diretoria do InstitutoBrasileiro de Concorrência e Inovação – IBCI (www.ibcibr.com.br). Professoracolaboradora da Faculdade de Direito de Franca-SP. Advogada associada noEscritório Nishioka e Gaban Advogados. gomes@ibcibr.com.brAluísio de Freitas Miele – Mestre em Direito Econômico pela FDRP/USP.Graduado em Direito pela UNESP. Membro do Grupo de Estudo deConcorrência e Inovação da Faculdade de Direito de Ribeirão Preto(FDRP/USP). Membro da Diretoria do Instituto Brasileiro de Concorrência eInovação -IBCI (www.ibcibr.com.br). Sócio do escritório Miele, Saran e ManiniSociedade de Advogados. Professor em cursos de graduação e pós-graduação.mieli@ibcibr.com.brJuliana Oliveira Domingues - Professora Doutora de Direito Econômico daFDRP/USP com pesquisa de Pós-doutorado realizada como Visiting-Scholar naUniversidade de Georgetown (EUA) pelo programa de International Scholar inResidence (2018). Secretária Nacional do Consumidor do Ministério da Justiçae Segurança Pública. Líder do grupo de pesquisa de Direito, Inovação e FashionLaw da FDRP/USP. Diretora Regional da Academic Society for Competition Law(ASCOLA). Presidente do Conselho Nacional de Defesa do Consumidor e doConselho Nacional de Combate à Pirataria. E-mail: juliana.domingues@usp.br.7

AutoresAlaís Aparecida Bonelli da Silva – Professora. Advogada. Especialista emDireito Corporativo e Compliance (EPD) e em Direito Digital e Proteção de Dados(EBRADI). Mestranda do programa Ética e Desenvolvimento da Faculdade deDireito de Ribeirão Preto (FDRP-USP).Ana Cristina Gomes – Doutoranda em Direito pela Universidad de Salamanca.Mestre e graduada em Direito pela UNESP. Coordenadora Chefe doDepartamento de Monografias do IBCCrim (2021/2022). Membra da Diretoria doInstituto Brasileiro de Concorrência e Inovação – IBCI. Professora colaboradorada Faculdade de Direito de Franca-SP. Advogada associada no EscritórioNishioka e Gaban Advogados.Ana Elisa Bertolin da Silva – Bacharel em Direito pela Universidade Estadualde Londrina. Membro fundadora da Equipe de Direito e Processo Penal da UEL.Advogada associada ao Escritório Nishioka e Gaban Advogados.Ana Paula Guimarães de Paula - Graduada em Direito (2020) pelaUniversidade Federal de Goiás. Coordenadora de Gabinete daSuperintendência-Geral do Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica.E-mail: anaguimaraesdepaula@gmail.com.André Luís Alvarenga Portella - Graduado em Direito pela Universidade deBrasília (UnB) e advogado em Brasília.Aron Vitor Fraiz Costa - Mestrando (bolsista CAPES) em Direito Econômico eDesenvolvimento pela PUCPR. Pós-graduando em Direito Empresarial Aplicadoe Análise Econômica do Direito pela Faculdade das Indústrias. Pesquisador deIniciação Científica 2019-2020. Orcid: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3668-4427.E-mail: aronvitor@gmail.com.Christophe Carugati Doctor in Law and Economics on Big Data andCompetition Law, Paris Center for Law and Economics (CRED), Paris IIPanthéon-Assas University. For correspondence: Christophe.Carugati@uparis2.frDiogo Kastrup Richter - LLM candidate in Economic Law and Development atPontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR/Brazil). Postgraduatediploma in Tax Law by the Instituto Brasileiro de Estudos Tributários (IBET/Brazil)and graduated in Law from PUCPR, with exchange program at Universidad deZaragoza (UNIZAR/Spain). Lawyer. E-mail: diogo.richter@pucpr.edu.br.8

Eduardo Oliveira Agustinho - Full Professor of Corporate Law at the LawSchool of Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR/Brazil) andAssociate Professor of the Post-Graduation Program of Law of PUCPR. Ph.D. o.agustinho@pucpr.br.Fernanda Lopes Martins - Mestre em Direito e Desenvolvimento no EstadoDemocrático de Direito pela Faculdade de Direito de Ribeirão Preto - USP(2019/2021). Advogada. Bacharel em Direito pela Faculdade de Direito deRibeirão Preto - USP.Frédéric Marty - CNRS – GREDEG – Université Côte d’Azur.Gabriel de Aguiar Tajra - Bacharel em Direito pela Faculdade de Direito deRibeirão Preto (FDRP-USP). Mestrando em Direito e Desenvolvimento pelaFaculdade de Direito de Ribeirão Preto (FDRP-USP). Membro fundador doNúcleo de Estudos de Antitruste e Regulatório da Faculdade de Direito deRibeirão Preto (NEAR-FDRP/USP).Giovana Vieira Porto - Mestranda na linha de pesquisa Transformações naOrdem Social e Econômica e Regulação do Programa de Pós-Graduação emDireito da Universidade de Brasília ("UnB"). Bacharelado em Direito pela UnB.Vencedora do Prêmio IBRAC-TIM 2017, na categoria Graduação.Isabela Maria Rosal Santos - Advogada e mestranda em Direito, Estado eConstituição pela Universidade de Brasília. Coordenadora de projetos do Centrode Direito, Internet e Sociedade (CEDIS-IDP). Professora de Direito Digital.Jeanne Mouton - PhD Student, CNRS- GREDEG - University of Côte d’Azur,France.José Matheus Muniz – Graduado em Direito pela Universidade de São Paulo eadvogado societário no Andrade Chamas Advogados.Julia Gonçalves Braga - Bacharela e mestranda em Direito pela Universidadede Brasília. Advogada em VMCA Advogados.Larissa Milkiewicz - Doutoranda (bolsista CAPES) em Direito Econômico eDesenvolvimento pela PUCPR. Mestre (bolsista CAPES) em Direito pelaPUCPR. Advogada atuante em Direito Ambiental e Agronegócio. Curitiba/PR.Orcid: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4755-0424. E-mail:larissa milkiewicz@hotmail.com.9

Lenisa Rodrigues Prado - Conselheira no CADE – Conselho Administrativo deDefesa Econômica e Doutoranda em Direito na UFMG.Luísa Campos Faria - Graduada em Direito (2019) e Mestranda em PropriedadeIntelectual e Transferência de Tecnologia para Inovação pela Universidade deBrasília. Analista de Políticas e Indústria II na Confederação Nacional daIndústria – CNI e Gerente na Women in Antitrust – WIA. E-mail:luisacamposf@gmail.com . ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4480-1363.Luiz Guilherme Branco - Assessor da Conselheira Lenisa Prado no CADE egraduado em Direito pela USP.Mariana Nascimento Silveira – Graduada e mestranda em Direito pelaUniversidade de São Paulo (Faculdade de Direito de Ribeirão Preto). Fez pósgraduação em Direito Tributário no Instituto Brasileiro de Estudos Tributários(IBET). Advogada empresarial no Andrade Chamas Advogados.Mariana Urban - LL.M Candidate at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law;Bachelor of Laws at University of São Paulo (FDRP/USP); Alumni of theEuropean, International and Comparative Law program at Universität Passau;Alumni of the International Business Law summer school at Bucerius Law School.Matheus Dalta Pimentel - Discente do 5º ano do curso de Direito do CentroUniversitário Antônio Eufrásio de Toledo de Presidente Prudente. Bolsista deIniciação Científica pelo Programa de Iniciação Científica - PICT e membro dogrupo de estudos avançados de Direito Econômico e Empresarial, mantidos pelamesma IES. E-mail: matheus dalta@hotmail.com.Mônica Tiemy Fujimoto - Professora de Direito Empresarial do InstitutoBrasiliense de Direito Público (IDP). Doutoranda e Mestre em Direito Empresariale Econômico pela Universidade de Brasília (UnB) e graduada em direito pelaUniversidade de São Paulo (USP). É Coordenadora de Relações Institucionaisdo Centro de Direito, Internet e Sociedade (CEDIS), Diretora de Eventos eComunicação do Women in Antitrust (WIA) e foi Coordenadora de AnáliseAntitruste no Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica (CADE). É Sócia doescritório MHBA Advogados e Consultora da Laura Schertel Mendes.Pietra Daneluzzi Quinelato - Mestre e Bacharel em Direito na Universidade deSão Paulo (USP), Especialista em Direito Digital e Proteção de Dados pelaEBRADI e ESA/SP, LLM em Direito e Prática Empresarial no CEU Law School,membro das comissões de Direito Digital, Direito da Moda e Privacidade eProteção de Dados da OAB/SP. Professora nas Faculdades Integradas CamposSalles. Pesquisadora do Grupo de Estudos em Direito Civil na Sociedade emRede, do Grupo de Concorrência e Inovação, ambos da USP, e da ComunidadeInternacional de Estudos em Direito Digital da Universidade Federal de10

Uberlândia. Colunista do portal Magis. Atua como coordenadora da área deDireito Digital do Mansur Murad Advogados. E-mail: pietraquinelato@gmail.com.Rubens Cantanhede Mota Neto - Graduado em Direito pela Universidade deBrasília, membro do Grupo de Estudos Constituição, Empresa e Mercadocoordenado pela professora Ana Frazão.Sergio L. B. F. Reis - Assessor da Conselheira Lenisa Prado no CADE.Especialista em Regulação. Mestre em Direito pela Universidade CândidoMendes, graduado em direito e pós-graduado em propriedade industrial pelaUERJ.11

SUMÁRIOApresentação . 14A new language for A.I. and the legal discourse (Eduardo Molan Gaban Vinícius Klein). 16Private enforcement of privacy breaches from Big Tech Companies under theGDPR, Competition law provisions and the Unfair Commercial PracticesDirective: substitutable or complementary legal grounds? (Jeanne Mouton) . 44As plataformas digitais e os novos contornos do problema dos conglomerados:Novos critérios para a análise de atos de concentração e a necessária mudançade paradigma do direito concorrencial (André Luís Alvarenga Portella) . 72Competition and Regulatory Challenges in Digital Markets: How to tackle theissue of self-preferencing? (Frédéric Marty) . 109Aspectos concorrenciais dos preços personalizados em plataformas digitais –Uma análise comparativa (Pietra Daneluzzi Quinelato) . 149Compliance concorrencial no mercado digital (Ana Cristina Gomes Ana ElisaBertolin da Silva Gabriel de Aguiar Tajra) . 168Compartilhamento de dados pessoais intragrupo econômico: a (in)suficiência doconsentimento como base legal e desafios para o Direito Antitruste (MônicaTiemy Fujimoto) . 187Instituições regulatórias e desenvolvimento no ambiente digital (Gabriel deAguiar Tajra) . 212Streaming, consumidor e concorrência (Sergio L. B. F. Reis Lenisa RodriguesPrado Luiz Guilherme Branco) . 235Rastreabilidade da produção agrícola através da tecnologia: Impactosambientais e econômicos (Larissa Milkiewicz Aron Vitor Fraiz Costa). 26412

Machine learning: Regulatory control of stock manipulation in social media(Mariana Urban) . 289Impactos concorrenciais do Pix no sistema financeiro (Ana Paula Guimarãesde Paula Luísa Campos Faria) .312Open Banking in the light of law & economics: Reduction of informationalasymmetries to foster competition (Eduardo Oliveira Agustinho DiogoKastrup Richter) . 331A análise concorrencial e a COVID-19: Os efeitos da pandemia na atuação doCADE (Giovana Vieira Porto Julia Gonçalves Braga) . 357O direito concorrencial em tempos de crise: Crisis failing e firm defense (MatheusDalta Pimentel) . 386A crise do Consumer Welfare Standard (Rubens Cantanhede Mota Neto). 409Trocas de informações sensíveis sobre termos e condições de trabalho no direitoantitruste brasileiro (Fernanda Lopes Martins) . 441Direito Antitruste e Big Data: a conexão da proteção e dados com o direito daconcorrência (Alaís Aparecida Bonelli da Silva José Matheus Muniz Mariana Nascimento Silveira). 471O direito à portabilidade de dados: Obrigações e limites impostos a concorrentes(Isabela Maria Rosal Santos Luísa Campos Faria) . 501Aspectos concorrenciais na implementação do 5G no Brasil (Isabela MariaRosal Santos Luísa Campos Faria) . 517Regulation in the digital economy. Is ex-ante regulation of “gatekeepers” anefficient and fair solution? (Christophe Carugati) . 53513

ApresentaçãoA presente obra é resultado do 3º Congresso Internacional do Instituto Brasileirode Concorrência e Inovação – IBCI e traz os melhores artigos selecionados nachamada de artigos do evento, bem como trabalhos dos palestrantes do eventorelacionados aos seus painéis e pesquisas apresentadas.O leitor contará reflexões de grandes professores brasileiros e estrangeiros, bemcomo de promissores pesquisadores de várias origens e linhas de pesquisas.Este livro, em linha com o 3º Congresso Internacional do IBCI, atribuiu foco aosprinciaís desafios postos às autoridades públicas de todo o munfo pelo fenômenodisruptivo dos mercados e ecossistemas digitais.A heterogeneidade geográfica e de olhares para o avanço dos mercados digitaismesmo que do ponto de vista concorrencial demonstra como aspectosinterdisciplinares e interinstitucionais são relevantes para a compreensão eabordagem do tema.Os mercados digitais trouxeram o debate concorrencial de volta ao espaçopúblico e os desafios inerentes a essa realidade são complexos e podem resultarem mudanças estruturais não apenas em marcos legislativos, guias e diretrizesde defesa da concorrência, mas também na forma pela qual o processoconcorrencial acontece na sociedade atual.O enfrentamento desse contexto de falta de encaixe entre os fundamentostradicionais da defesa da concorrência e a nova realidade representa umaoportunidade de aperfeiçoamento da atuação estatal não apenas para osmercados digitais, mas de forma ampla. Por outro lado, uma resposta excessivado antitruste ou da intervenção estatal regulatória como resultado de umestranhamento com os novos processos de mercado e modelos de negócio podeimplicar risco à inovação não apenas no momento presente, mas tambémeliminar ciclos futuros de oportunidades e avanços.A relevância dessas questões tem feito com que diversas entidades tenham sedebruçado sobre o assunto e o IBCI apresenta esta obra como contribuição paraeste grande debate de forma interdisciplinar e plural e partir de uma abordagemacadêmica de excelência, valores estes que também guiam o IBCI.Eduardo M. Gaban / Vinícius Klein14

PrefaceThis book is the result of the 3rd IBCI International Conference on Competitionand Innovation and brings the best articles selected in the event's call for articles,as well as papers by the event's speakers related to their panels and researchprojects tackled in the Conference.The reader will access reflections from great Brazilian and foreign Professors,Scholars, as well as promising researchers from various origins and lines ofresearch. This book, in line with the 3rd IBCI International Conference, focusedon the main challenges posed to public authorities around the world by thedisruptive phenomenon of digital markets and digital ecosystems.The geographic heterogeneity and views of the advancement of digital markets,even from a competitive point of view, demonstrates how interdisciplinary andinterinstitutional aspects are crucial to the understanding and approach of thematter.Digital markets have brought the competitive debate back to the public arena andthe challenges inherent in this reality are complex and can result in structuralchanges not only in legislative frameworks, guides, and guidelines for the defenseof competition, but also in the way in which the competitive process happenstoday.Confronting this context of lack of fit between the foundations of competitionpolicy and the new reality represents an opportunity to improve the state'sperformance not only for digital markets, but in a broader way. On the other hand,an excessive antitrust response or regulatory state intervention in response to anestrangement from the new market processes and business models can imply arisk to innovation not only in the present moment, but also eliminate future cyclesof opportunities and advances.The relevance of these issues has meant that several entities have addressedthe subject and IBCI presents this work as a contribution to this great debate inan interdisciplinary and plural way, based on an academic approach ofexcellence, values that also guide IBCI.Eduardo M. Gaban / Vinícius Klein15

A new language for A.I. and the legal discourse1Eduardo Molan GabanVinícius KleinAbstract: The digital economy presents several challenges to antitrust lawenforcement. The traditional legal approach to define liability, as well as thetraditional enforcement toolkit are no longer effective. This context is present inthe case of algorithmic collusion. The central role of the concept of agreementand the focus on the results can still be effective to detect collusions outsidedigital markets, as digitalization is increasingly present in markets. On the otherhand, artificial intelligence (A.I.) and blockchains make virtually impossible theidentification of the authorship of crimes or offenses and pose difficulties for thetraditional normative matrix. This paper aims to address this issue of algorithmiccollusion in an innovative way and the use of A.I in favor of antitrust enforcement.The proposed solution to recover law effectiveness would comprehend acombination of antitrust and compliance by design in programming, producing amutation in the DNA Competition Policy, expanding, and modernizing the antitrustlaw enforcement toolkit and assuring its effectiveness in the digital markets.Keywords: Digital economy. Artificial intelligence. CompetitionCompliance by design. Liability. Effects. Authorship. Presumptions.policy.IntroductionAfter decades of quietude, antitrust has become “sexy again” 2. Thedebates are more explicit and profound, and they are not restricted to theclose community of experts but include the public opinion forum. Theemerge of digital markets is the main ingredient of this second revival ofthe antitrust movement3 and now the debate is not only restricted todifferent perspectives of Law and Economics but also technology issuesThis paper was selected by the Academic Society for Competition Law (ASCOLA) as one of the best papersin 2021 related to antitrust and digital economy, and it was presented by the authors in the Panel I –Algorithms and Antitrust, in the 16th annual event of Ascola.2SHAPIRO, Carl. Antitrust in a time of populism. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 61 (C),2018, p. 714.3According to HOFSTADER the Antitrust Movement in USA reached his highest point in 1914 with theClayton Act and the creation of the Federal Trade Commission, but after this progressive era and until1937 there as a phase of neglect, followed by a first revival in 1938 with the New Deal, but this time withno strong public sentiment against big business as in the progressive era. In the 1960s the antitrustmovement had faded away again. (HOFSTADTER, Richard. What Happened to the Antitrust Movement?In: HOFSTADTER, Richard. The Paranoid Style in American Politics and other essays. New York: VintageBooks, 2008, p. 193-204).116

and debates. Due to an intense transformation in the business environmentand in the competition process itself this rich environment of newchallenges has been accompanied by new perspectives and theories, suchas the New Brandeis Movement or Hipster Antitrust4. The most salientchallenge produced by this new business environment is the process ofcompetition5. In this specific topic, a possible adjustment of the antitruststandard of analysis and the toolkit used in the enforcement will benecessary to tackle the new reality of digital markets. Several reports aboutthe challenges of the digital market economy have been issued by antitrustauthorities and international actors.The presence of algorithms6 in our daily lives has severalrepercussions for antitrust analysis, but it is the use of machine learningthat has made the question of collusion more problematic as will beexplored in this paper. The discussion of the topic will make use of theframework presented in STUCKE & ERZACHI7, with four possiblescenarios of algorithmic pricing in collusion: messenger, hub and spoke,predictable agent and autonomous machine.In the first two scenarios the algorithm may be just a method by whichcollusive behavior is implemented. In the messenger scenario there is anagreement made by humans and the algorithm is just the messenger,executing orders such as monitor prices or punish deviants8. In the “huband spoke” collusion algorithms are a central hub to coordinate4These movement, despite its heterogeneity, has it its core the dissatisfaction with the consumer welfarestandard developed by the Chicago School. A starting point is: Khan, Lina. Amazon Antitrust Paradox.Yale Law Journal, 126 (3), pp. 710-805, 2016.5According to the UK CMA Working Paper on Pricing Algorithms, “An algorithm is any well-definedcomputational procedure that takes some value, or set of values, as input and produces some value, or setof values as output.”6An algorithm can be defined as: “a computer algorithm is a set of steps to accomplish a task that isdescribed precisely enough that a computer can run it.” Cormen, Thomas H. Algorithms Unlocked.Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013, p. 2.7EZRACHI, Ariel; STUCKE, Maurice. Artificial Intelligence & Collusion: When Computers InhibitCompetition. In: University of Illinois Law Review, 2017, pp. 1775-1810.8“UNDER OUR FIRST collusion scenario, Messenger, humans are the masters who agree to collude andmap out the cartel. The computer algorithms are the messenger, which the cartel members program to helpeffectuate the cartel and monitor and punish any deviation from the cartel agreement. (Ezrachi, Ariel andStucke, Maurice E. Virtual Competition: the promise and perils of the algorithm-driven economy.Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016, p.39)17

competitors’ pricing or activities9, there is no human order to execute, butthe use of an algorithm or the same algorithm by competitors that alignprices.Therefore, despite some legal challenges presented by those typesof collusion, they are not the subject of analysis of the present study sincethey do not represent a challenge to the antitrust toolkit.The focus of this paper is to discuss the other two scenarios:“predictable agent” and “autonomous machine” or “digital eye”. In those twocases the algorithms are unilaterally designed, in the end resulting in a tacitcollusion with no need of prior agreements among competitors. The“autonomous machine” is an even more grey zone, and it reflects thesituation in which the algorithm is designed exclusively to maximize profit.Moreover, the algorithm is complex enough to learn by itself and engage inan anticompetitive conduct – tacit collusion – with no influence of humans.In the “predictable agent” case, the algorithm is programmed tomonitor prices and increase profit, so when the price increase issustainable, the competitor follows and produces autonomous tacitcollusion10. The difference from the “autonomous machine” or “digital eye”scenario is the presence of the stability of the collusion since no deviationis possible without being caught by other competitors' algorithms and theabsence of any specific order to respond in a specific way to an rningandexperimentation11.In view of the enforcement challenge in those scenarios, this paperproposes the adoption of a mandatory compliance by design inprogramming such algorithms as an option to solve the matter.To achieve this task, in the first section of this article will be presentedthe typology of collusions on the digital markets, as well as the concepts9Ezrachi, Ariel and Stucke, Maurice E. Virtual Competition: the promise and perils of the algorithm-driveneconomy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016, p. 46.10 Ezrachi, Ariel and Stucke, Maurice E. Virtual Competition: the promise and perils of the algorithmdriven economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016, p. 61.11 Ezrachi, Ariel and Stucke, Maurice E. Virtual Competition: the promise and perils of the algorithmdriven economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016, p. 74.18

and functionalities of algorithms as means or reasons to facilitate,implement or result in a collusive behavior. The next section will evaluatethe efficacy of the traditional legal framework to combat collusion in theenvironment of the digital economy. The main problems, for instance theobstacles on evidencing authorship for collusive behavior derived from A.I.,will be discussed. The third section will explore possible solutions in thenormative level to address the problem of producing adequate antitrustenforcement of algorithmic collusion. Specifically, this section shall tacklethe idea of compliance by design, its potential to adjust the economicincentives for deterrence, vis-à-vis the legal hurdles for its concretion insome jurisdictions. Following the third section, the concluding remarks willbring up an organized presentation of the concepts, main reflections, andinsights from this innovative and rich discussion.Section I – Collusive behavior and algorithmsThe framework adopted for discussion is the theoretical definitionproposed by STUCKE & ERZACHI12 and already presented in theintroduction.The “messenger” and the “hub and spoke” cartel are well known bycompetition authorities and have the same effect than a hard-core cartel inany other market and several jurisdictions have already investigated andcondemned conducts of this model. Among the examples of “messenger”,it is worth mentioning the case of selling posters by Amazon by DavidTopkins13 which was investigated by the US Department of Justice and a12Although there are other classifications proposed by the specialized literature, the fact is that theframework proposed by Stucke and Erzachi was very well received by the academic environment, bothenabling a standard of background analysis with a

Diogo Kastrup Richter - LLM candidate in Economic Law and Development at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR/Brazil). Postgraduate diploma in Tax Law by the Instituto Brasileiro de Estudos Tributários (IBET/Brazil) and graduated in Law from PUCPR, with exchange program at Universidad de Zaragoza (UNIZAR/Spain). Lawyer.