Transcription

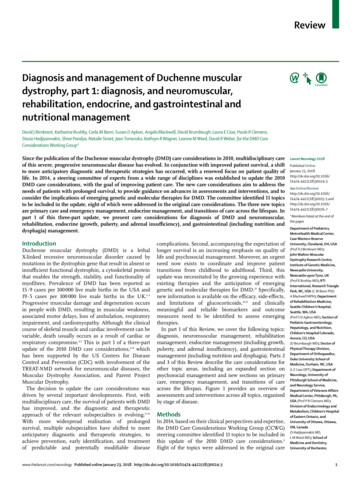

ReviewDiagnosis and management of Duchenne musculardystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and neuromuscular,rehabilitation, endocrine, and gastrointestinal andnutritional managementDavid J Birnkrant, Katharine Bushby, Carla M Bann, Susan D Apkon, Angela Blackwell, David Brumbaugh, Laura E Case, Paula R Clemens,Stasia Hadjiyannakis, Shree Pandya, Natalie Street, Jean Tomezsko, Kathryn R Wagner, Leanne M Ward, David R Weber, for the DMD CareConsiderations Working Group*Since the publication of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) care considerations in 2010, multidisciplinary careof this severe, progressive neuromuscular disease has evolved. In conjunction with improved patient survival, a shiftto more anticipatory diagnostic and therapeutic strategies has occurred, with a renewed focus on patient quality oflife. In 2014, a steering committee of experts from a wide range of disciplines was established to update the 2010DMD care considerations, with the goal of improving patient care. The new care considerations aim to address theneeds of patients with prolonged survival, to provide guidance on advances in assessments and interventions, and toconsider the implications of emerging genetic and molecular therapies for DMD. The committee identified 11 topicsto be included in the update, eight of which were addressed in the original care considerations. The three new topicsare primary care and emergency management, endocrine management, and transitions of care across the lifespan. Inpart 1 of this three-part update, we present care considerations for diagnosis of DMD and neuromuscular,rehabilitation, endocrine (growth, puberty, and adrenal insufficiency), and gastrointestinal (including nutrition anddysphagia) management.IntroductionDuchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a lethalX-linked recessive neuromuscular disorder caused bymutations in the dystrophin gene that result in absent orinsufficient functional dystrophin, a cytoskeletal proteinthat enables the strength, stability, and functionality ofmyofibres. Prevalence of DMD has been reported as15·9 cases per 100 000 live male births in the USA and19·5 cases per 100 000 live male births in the UK.1–3Progressive muscular damage and degeneration occursin people with DMD, resulting in muscular weakness,associated motor delays, loss of ambulation, respiratoryimpairment, and cardiomyopathy. Although the clinicalcourse of skeletal muscle and cardiac involvement can bevariable, death usually occurs as a result of cardiac orrespiratory compromise.4,5 This is part 1 of a three-partupdate of the 2010 DMD care considerations,6–8 whichhas been supported by the US Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention (CDC) with involvement of theTREAT-NMD network for neuromuscular diseases, theMuscular Dystrophy Association, and Parent ProjectMuscular Dystrophy.The decision to update the care considerations wasdriven by several important developments. First, withmultidisciplinary care, the survival of patients with DMDhas improved, and the diagnostic and therapeuticapproach of the relevant subspecialties is evolving.9–12With more widespread realisation of prolongedsurvival, multiple subspecialties have shifted to moreanticipatory diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, toachieve prevention, early identification, and treatmentof predictable and potentially modifiable diseasecomplications. Second, accompanying the expectation oflonger survival is an increasing emphasis on quality oflife and psychosocial management. Moreover, an urgentneed now exists to coordinate and improve patienttransitions from childhood to adulthood. Third, thisupdate was necessitated by the growing experience withexisting therapies and the anticipation of emerginggenetic and molecular therapies for DMD.13 Specifically,new information is available on the efficacy, side-effects,and limitations of glucocorticoids,14,15 and clinicallymeaningful and reliable biomarkers and outcomemeasures need to be identified to assess emergingtherapies.In part 1 of this Review, we cover the following topics:diagnosis, neuromuscular management, rehabilitationmanage ment, endocrine management (including growth,puberty, and adrenal insufficiency), and gastro intestinalmanagement (including nutrition and dysphagia). Parts 2and 3 of this Review describe the care considerations forother topic areas, including an expanded section onpsychosocial management and new sections on primarycare, emergency management, and transitions of careacross the lifespan. Figure 1 provides an overview ofassessments and interventions across all topics, organisedby stage of disease.MethodsIn 2014, based on their clinical perspectives and expertise,the DMD Care Considerations Working Group (CCWG)steering committee identified 11 topics to be included inthis update of the 2010 DMD care considerations.6Eight of the topics were addressed in the original carewww.thelancet.com/neurology Published online January 23, 2018 cet Neurology 2018Published OnlineJanuary 23, 3See 18)30025-5 *Members listed at the end ofthe paperDepartment of Pediatrics,MetroHealth Medical Center,Case Western ReserveUniversity, Cleveland, OH, USA(Prof D J Birnkrant MD);John Walton MuscularDystrophy Research Centre,Institute of Genetic Medicine,Newcastle University,Newcastle upon Tyne, UK(Prof K Bushby MD); RTIInternational, Research TrianglePark, NC, USA (C M Bann PhD,A Blackwell MPH); Departmentof Rehabilitation Medicine,Seattle Children’s Hospital,Seattle, WA, USA(Prof S D Apkon MD); Section ofPediatric Gastroenterology,Hepatology, and Nutrition,Children’s Hospital Colorado,Aurora, CO, USA(D Brumbaugh MD); Doctor ofPhysical Therapy Division,Department of Orthopaedics,Duke University School ofMedicine, Durham, NC, USA(L E Case DPT); Department ofNeurology, University ofPittsburgh School of Medicine,and Neurology Service,Department of Veterans AffairsMedical Center, Pittsburgh, PA,USA (Prof P R Clemens MD);Division of Endocrinology andMetabolism, Children’s Hospitalof Eastern Ontario, andUniversity of Ottawa, Ottawa,ON, Canada(S Hadjiyannakis MD,L M Ward MD); School ofMedicine and Dentistry,University of Rochester,1

ReviewNeuromuscularmanagementStage 1:At diagnosisStage 2:Early ambulatoryStage 3:Late ambulatoryStage 4:Early non-ambulatoryStage 5:Late non-ambulatoryLead the multidisciplinary clinic; advise on new therapies; provide patient and family support, education, and genetic counsellingEnsure immunisation schedule is completeAssess function, strength, and range of movement at least every 6 months to define stage of diseaseDiscuss use of glucocorticosteroidsInitiate and manage use of glucocorticosteroidsHelp navigate end-of-life careRefer female carriers to cardiologistRehabilitationmanagementProvide comprehensive multidisciplinary assessments, including standardised assessments, at least every 6 monthsProvide direct treatment by physical and occupational therapists, and speech-language pathologists, based on assessments and individualised to the patientAssist in prevention of contracture or deformity, overexertion, and falls; promoteenergy conservation and appropriate exercise or activity; provide orthoses,equipment, and learning supportContinue all previous measures; provide mobility devices, seating, supported standing devices, and assistive technology;assist in pain and fracture prevention or management; advocate for funding, access, participation, and self-actualisationinto adulthoodGastrointestinal andnutritional managementEndocrinemanagementMeasure standing height every 6 monthsAssess non-standing growth every 6 monthsAssess pubertal status every 6 months starting by age 9 yearsProvide family education and stress dose steroid prescription if on glucocorticosteroidsInclude assessment by registered dietition nutritionist at clinic visits (every 6 months); initiate obesity prevention strategies; monitor for overweight and underweight, especially during critical transition periodsProvide annual assessments of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and calcium intakeAssess swallowing dysfunction, constipation, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, and gastroparesis every 6 monthsInitiate annual discussion of gastrostomy tube as part of usual careRespiratorymanagementProvide spirometry teaching and sleep studies as needed (low risk of problems)Assess respiratory function at least every 6 monthsEnsure immunisations are up to date: pneumococcal vaccines and yearly inactivated influenza vaccineInitiate use of lung volume recruitmentBegin assisted cough and nocturnal ventilationConsult cardiologist; assess withelectrocardiogram and echocardiogram*or cardiac MRI†OrthopaedicmanagementBone healthmanagementCardiacmanagementAdd daytime ventilationAssess cardiac function annually;initiate ACE inhibitors or angiotensinreceptor blockers by age 10 yearsAssess cardiac function at least annually, more often if symptoms or abnormal imaging are present; monitor for rhythmabnormalitiesUse standard heart failure interventions with deterioration of functionAssess with lateral spine x-rays (patients on glucocorticosteroids: every 1–2 years; patients not on glucocorticosteroids: every 2–3 years)Refer to bone health expert at the earliest sign of fracture (Genant grade 1 or higher vertebral fracture or first long-bone fracture)Assess range of motion at least every 6 monthsRefer for orthopaedic surgery if needed(rarely necessary)Monitor for scoliosis annuallyMonitor for scoliosis every 6 monthsRefer for surgery on foot and Achilles tendon to improve gait in selectedsituationsConsider intervention for foot position for wheelchair positioning; initiateintervention with posterior spinal fusion in defined situationsTransitionsPsychosocialmanagementAssess mental health of patient and family at every clinic visit and provide ongoing support2Provide neuropsychological evaluation/interventions for learning, emotional, and behavioural problemsAssess educational needs and available resources (individualised education programme, 504 plan); assess vocational support needs for adultsPromote age-appropriate independence and social developmentEngage in optimistic discussions aboutthe future, expecting life intoadulthoodFoster goal setting and futureexpectations for adult life; assessreadiness for transition (by age12 years)Initiate transition planning for health care, education, employment, and adult living (by age 13–14 years); monitor progressat least annually; enlist care coordinator or social worker for guidance and monitoringProvide transition support and anticipatory guidance about health changeswww.thelancet.com/neurology Published online January 23, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30024-3

Reviewconsiderations: (1) diagnosis, (2) neuromuscular manage ment, (3) rehabilitation management, (4) gastrointestinaland nutritional management, (5) respiratory manage ment, (6) cardiac management, (7) orthopaedic andsurgical management, and (8) psychosocial management.Three topics are new: (9) primary care and emergencymanagement, (10) endocrine management (includinggrowth, puberty, adrenal insufficiency, and bone health),and (11) transitions of care across the lifespan.The guidance in this update is not conventionallyevidence based. As is typical for a rare disease, fewlarge-scale randomised controlled trials (RCTs) havebeen completed for DMD, with the exception of studiesof corticosteroids.16 Therefore, as for the 2010 DMD careconsiderations,6,7 guidance was developed using amethod that queries a group of experts on the appro priateness and necessity of specific assessments andinterventions, using clinical scenarios.17 This method isintended to objectify expert opinion, and to make theguidance a true reflection of the views and practices ofan expert panel, based on their interpretation andapplication of the existing scientific literature. Using thisapproach, we were able to produce an essential toolkitfor DMD care; only assessments and interventions thathave been deemed both appropriate and necessary arerecommended.A comprehensive literature review was done toidentify articles relevant to DMD care for each topicarea, with the addition of key words for the new topics.A full description of the literature review strategy, tableof search terms, and summaries of relevant literatureare available in the appendix. From the search results,the steering committee selected articles containinginformation that might require the 2010 careconsiderations to be updated. Clinical scenarios werethen developed on the basis of the content of thosearticles. For each of the 11 topic areas, a committee ofexperts was assembled. Using the RAND Corporation–University of California Los Angeles AppropriatenessMethod (RAM),6,17 the committees established whichassessments and interventions were both appropriateand necessary for the various clinical scenarios. For theRAM process, the committees had two rounds toestablish appropriateness followed by one or tworounds on necessity. For the following sections, not allsteps of the two-stage RAM rating process wererequired, either because of a lack of new literature sincethe 2010 care considerations were developed, or becauseimmediate unanimous agreement was reached amongFigure 1: Comprehensive care of individuals with Duchenne musculardystrophyCare for patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy is provided by amultidisciplinary team of health-care professionals; the neuromuscular specialistserves as the lead clinician. The figure includes assessments and interventionsacross all disease stages and topics covered in this three-part Review.*Echocardiogram for patients 6 years or younger. †Cardiac MRI for patients olderthan 6 years.committee members on the appropriateness andnecessity of interventions: diagnosis, neuromuscularmanagement, respiratory management, cardiacmanagement, orthopaedic and surgical management,and psychosocial management. Additionally, the RAMmethod was not deemed to be applicable for two of thenew sections: primary care and emergencymanagement, and transitions of care across thelifespan. The committees for these sections reachedconsensus during their discussions without first ratingclinical scenarios.Rochester, NY, USA(S Pandya DPT); Rare Disordersand Health Outcomes Team,National Center on BirthDefects and DevelopmentalDisabilities, Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention,Atlanta, GA, USA (N Street MS);Medical Nutrition Consultingof Media LLC, and Children’sHospital of Philadelphia,Philadelphia, PA, USA(J Tomezsko PhD); Center forWhen to suspect DMDUnexplained increase intransaminasesIf family history of DMDAny suspicion of abnormalmuscle functionCreatine kinasenot increasedIf no family history of DMDNot walking by 16–18 months,Gowers’ sign, or toe walking(any age, expecially 5 years old)Testing for serum creatinekinaseCreatine kinaseincreasedTesting for DMD genedeletion or duplicationNo mutation foundGenetic sequencingNo mutation foundMuscle biopsyMutation foundDystrophin absentDystrophin presentDMD unlikely; consider alternative diagnosesMutation foundDMD diagnosisMost commonly observed early signs and symptoms in patients with DMDMotor Abnormal gait Calf pseudohypertrophy Inability to jump Decreased endurance Decreased head control when pulled to sit Difficulty climbing stairs Flat feet Frequent falling or clumsiness Gowers’ sign on rising from floor Gross motor delay Hypotonia Inability to keep up with peers Loss of motor skills Muscle pain or cramping Toe walking Difficulty running or climbingNon-motor Behavioural issues Cognitive delay Failure to thrive or poor weight gain Learning and attentional issues Speech delay or articulation difficultiesFigure 2: Diagnosis of Duchenne muscular dystrophyDescribed early signs and symptoms of DMD are based on Ciafaloni and colleagues.18 DMD Duchenne musculardystrophy.www.thelancet.com/neurology Published online January 23, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30024-33

ReviewGenetic Muscle Disorders,Kennedy Krieger Institute, andJohns Hopkins School ofMedicine, Baltimore, MD, USA(Prof K R Wagner MD); andDivision of Endocrinology andDiabetes, Golisano Children’sHospital, University ofRochester Medical Center,Rochester, NY, USA(D R Weber MD)Correspondence to:Prof David J Birnkrant,Department of Pediatrics,MetroHealth Medical Center,Case Western Reserve University,Cleveland, OH 44109, USAdbirnkrant@metrohealth.orgFor more on theTREAT-NMD network seehttp://www.treat-nmd.eu/For more on the MuscularDystrophy Association seehttps://www.mda.org/For more on Parent ProjectMuscular Dystrophysee http://www.parentprojectmd.org/See Online for appendixDiagnosisAchieving a timely and accurate diagnosis of DMD is acrucial aspect of care. The method for diagnosing DMDhas not changed significantly since 2010 (figure 2).6 Thediagnostic process typically begins in early childhoodafter suggestive signs and symptoms are noticed, suchas weakness, clumsiness, a Gowers’ sign, difficulty withstair climbing, or toe walking. Prompt referral to aneuromuscular specialist, with input from a geneticistor genetic counsellor, can avoid diagnostic delay.18 Lesscommonly, the diagnosis is considered as a result ofdevelopmental delay19 or increased concentrations ofserum enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase,aspartate aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, orcreatine kinase. Occasionally, an increased alanineaminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, or lactatedehydrogenase concentration prompts an inappropriatefocus on hepatic dysfunction, delaying the diagnosis ofDMD.Because approximately 70% of individuals with DMDhave a single-exon or multi-exon deletion or duplicationin the dystrophin gene, dystrophin gene deletion andduplication testing is usually the first confirmatory test.Testing is best done by multiplex ligation-dependentprobe amplification (MLPA)20 or comparative genomichybridisation array,21 since use of multiplex PCR canPanel 1: Roles and responsibilities of the neuromuscular specialist in the care ofpatients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy Assess and characterise each patient’s unique disease trajectory over time usingvalidated assessment tools, aiming to establish a patient’s expected clinical course andto advise on prognosis and potential complications Use assessment information to select therapeutic interventions that define a customisedtreatment plan designed to meet the particular needs and goals of each patient andfamily, optimising outcomes and quality of life as defined by the individual patient andfamily Engage specific clinicians who can enact the designated assessments, interventions, andtreatment plan, ideally in the context of a dedicated, multidisciplinary DMD clinic that isled, administered, and coordinated by the neuromuscular specialist; assist in the care offemale carriers, including cardiac assessment Be the first-line medical advisor to patients and their families as they define and revisetheir individual care goals over time, helping them to personalise their risk-to-benefitanalysis of therapeutic interventions, including: Technological interventions for respiratory and cardiac management Surgical and non-surgical interventions, such as spinal fusion, contracturemanagement, and provision of aids and appliances Pharmacological interventions, such as glucocorticoid therapy, emergingtherapies, and patient participation in clinical research trials of investigationaldrugs Be an advocate for high-quality DMD care at patients’ institutions and in theircommunities, addressing issues such as transition of care from paediatric to adultclinical providers and provision of hospital care that is designed to address patients’unique medical, physical, and psychosocial needs Help patients and families navigate end-of-life care in a way that preserves comfort,dignity, and quality of life as defined by each individual patient and family4only identify deletions. Identification of the boundariesof a deletion or duplication mutation by MLPA orcomparative genomic hybridisation array might indicatewhether the mutation is predicted to preserve or disruptthe reading frame. If deletion or duplication testing isnegative, genetic sequencing should be done to screenfor the remaining types of mutations that are attributedto DMD (approximately 25–30%).22 These mutationsinclude point mutations (nonsense or missense), smalldeletions, and small duplications or insertions, whichcan be identified using next-generation sequencing.23–25Finally, if genetic testing does not confirm a clinicaldiagnosis of DMD, then a muscle biopsy sample shouldbe tested for the presence of dystrophin protein byimmuno histochemistry of tissue cryosections or bywestern blot of a muscle protein extract.Female carriersFamily members of an individual with DMD shouldreceive genetic counselling to establish who is at risk ofbeing a carrier. Carrier testing is recommended forfemale relatives of a boy or man who has been geneticallyconfirmed to have DMD. If the relative is a child, thenthe American Medical Association ethical guidelines forgenetic testing of children should be followed.26 Onceidentified, female carriers have several reproductivechoices to consider, including preimplantation geneticdiagnosis or prenatal genetic testing through chorionicvillus or amniotic fluid sampling. Female carriers alsoneed medical assessment and follow-up, as described inthe section on cardiac management in part 2 of thisReview.Newborn screeningThe feasibility of newborn screening for DMD was firstshown in the mid-1970s27 through measurement ofcreatine kinase concentrations from dried blood spots.Recently, a two-tier newborn screening diagnosticsystem was reported,2 in which samples that revealed anincreased creatine kinase concentration were then testedfor dystrophin gene mutations. Newborn screeningstudies for DMD have been done in several countries,but most have been discontinued,2,28 and DMD is notcurrently included on the Recommended UniformScreening Panel,29 which is largely restricted toneonatal-onset disorders for which early treatmentshows improved outcome. However, renewed interest innewborn screening has been building as a result ofsupport among stakeholders and because emergingDMD therapies might prove to be most effective if theyare initiated before symptom onset.30,31Neuromuscular managementAfter diagnosis, the neuromuscular specialist will serveas the lead clinician, taking overall responsibility forcare of the person with DMD and performing multipleroles and responsibilities across the individual’s lifetimewww.thelancet.com/neurology Published online January 23, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30024-3

Review(panel 1). The neuromuscular specialist is uniquelyqualified to guide patients and their families throughthe increasingly complex and technological diagnosticand therapeutic landscape of contemporary DMD care.Timeline and scusswith familyDiscusssteroidsuse of steroidswith familyAdrenal insufficiencyPatient and family education Educate on signs, symptoms, and management ofadrenal crisisPrescribe intramuscular hydrocortisone foradministration at home 50 mg for children aged 2 years old 100 mg for children aged 2 years old and adultsStress dosing for patients taking 12 mg/m² per dayof prednisone/deflazacort daily Might be required in the case of severe illness,major trauma, or surgery Administer hydrocortisone at 50–100 mg/m² per dayAssessmentsConsistent and reproducible clinical assessments ofneuromuscular function done by trained practitionersunderpin the management of DMD. Assessments de scribed in the 2010 care considerations remain valid,and clinics should use a set of tests with which they arecomfortable and for which they understand the clinicalcorrelates. Multidisciplinary team members must worktogether to optimise consistency and avoid unnecessarytest duplication. Suggested assessments are shown inthe appendix and are discussed in the section on rehabil itation management. Newer studies have shown the value of minimum clinically important differences,pre dictive capabilities of standardised functional asses s ments, and ranges of optimum responsiveness, confirming the importance of standardised functionalassessments across a patient’s lifespan.32–35 Additionally,new assessment tools are helping to guide the management of older, non-ambulatory individuals, illustratingthe importance of clinical testing throughout life.InterventionsPhysiotherapy, as described in the section onrehabilitation management, and treatment with gluco corticoids remain the mainstays of DMD treatment andshould continue after loss of ambulation. Figure 3describes glucocorticoid initiation and use.36 Thebenefits of long-term gluco corticoid therapy have beenshown to include loss of ambulation at a later age,preserved upper limb and respiratory function, andavoidance of scoliosis surgery.37 Recent studies confirmthe benefits of starting glucocorticoids in youngerchildren, before significant physical decline;38,39 anongoing trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02167217)of weekend dosing in boys younger than 30 months willsoon yield additional insights. Although the benefits ofglucocorticoid therapy are well established, uncertaintyremains about which glucocorticoids are best and atwhat doses.40 These uncertainties increase the risk ofundertreatment or overtreatment, which could confoundthe results of trials of innovative therapies. Large-scalenatural history and cohort studies confirm prolongationof ambulation from a mean of 10·0 years in individualstreated with less than 1 year of corticosteroids to a meanof 11·2 years in individuals treated with daily prednisoneand 13·9 years in individuals taking daily deflazacort.41In a few studies, weekend-only dosing of prednisone hasshown efficacy equal to that of daily dosing.41,42 A phase3 double-blind RCT compared deflazacort 0·9 mg/kgper day, deflazacort 1·2 mg/kg per day, prednisone0·75 mg/kg per day, and placebo. All treatment groupshad improved muscle strength compared with placeboBegin steroid regimen Before substantial physical decline After discussion of side-effects After nutrition consultationRecommended starting dose Prednisone or prednisolone 0·75 mg/kg per dayOR Deflazacort 0·9 mg/kg per dayDosing changesIf side-effects unmanageable or intolerable Reduce steriods by 25–33% Reassess in 1 monthIf functional decline Increase steroids to target dose per weight on thebasis of starting dose Reassess in 2–3 monthsUse in non-ambulatory stage Continue steroid use but reduce dose as necessary tomanage side-effects Older steroid-naive patients might benefit frominitiation of a steroid regimenDo not stop steroids abruptly Implement PJ Nicholoff steroid-tapering protocol²⁹ Decrease dose by 20–25% every 2 weeks Once physiological dose is achieved (3 mg/m2per day of prednisone or deflazacort) switch tohydrocortisone 12 mg/m2 per day divided intothree equal doses Continue to wean dose by 20–25% every weekuntil dose of 2·5 mg hydrocortisone every otherday is achieved After 2 weeks of dosing every other day, discontinuehydrocortisone Periodically check morning CRH-stimulated orACTH-stimulated cortisol concentration until HPAaxis is normal Continue stress dosage until HPA axis has recovered(might take 12 months or longer)Figure 3: Care considerations for glucocorticoid (steroid) initiation and use for patients with Duchennemuscular dystrophyACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone. CRH corticotropin-releasing hormone. HPA hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal.and deflazacort was associated with less weight gainthan prednisone.14 The benefit-to-risk ratio of deflazacortcompared with prednisone is being studied further in anongoing double-blind trial.15Emerging treatmentsThe drug development pipeline for DMD has changeddramatically since the publication of the 2010 careconsiderations, and the full list of DMD treatment trialschanges continually; updated information is available atClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International ClinicalTrials Registry Platform. DMD is a rare disease, and theincreasing number of DMD trials is a challenge forclinical trial capacity because of the low numbers ofpatients who qualify for participation. The need tooptimise patient recruitment is expected to promoteinitiatives supporting trial readiness, such as patientregistries, identification of clinically significant outcomemeasures, and natural history studies.In August, 2014, ataluren was granted conditionalmarketing authorisation by the European Commissionfor use in the European Union, targeting theapproximately 11% of boys with DMD caused by a stopwww.thelancet.com/neurology Published online January 23, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30024-3For ClinicalTrials.gov seehttps://clinicaltrials.gov/For the WHO InternationalClinical Trials Registry Platformsee http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/5

Reviewcodon in the dystrophin gene.43,44 In September, 2016, theUS Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved useof eteplirsen, which targets the approximately 13% ofboys with a mutation in the dystrophin gene that isamenable to exon 51 skipping,45 via an acceleratedapproval pathway. Ataluren and eteplirsen are the firstof a series of mutation-specific therapies to gainregulatory approval. Other dystrophin restorationtherapies are in development and some are near or inregulatory review.13 The FDA has also granted fullapproval for deflazacort, making this the firstglucocorticoid with a labelled indication specifically forDMD.Other drug classes in trials for DMD include drugstargeting myostatin, anti-inflammatory and antioxidantmolecules, compounds to reduce fibrosis, drugs toimprove vasodilatation, drugs to improve m

Stasia Hadjiyannakis, Shree Pandya, Natalie Street, Jean Tomezsko, Kathryn R Wagner, Leanne M Ward, Da vid R Weber, for the DMD Care Considerations Working Group* Since the publication of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) care considerations in 2010, multidisciplinary care of this severe, progressive neuromuscular disease has evolved.