Transcription

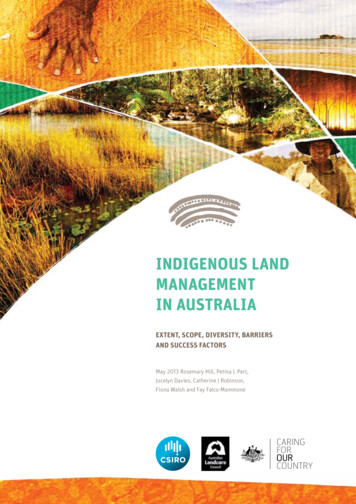

World Heritage Sites andIndigenous Peoples’ RightsEdited by Stefan Disko and Helen TugendhatIWGIA – Document 129Copenhagen – 2014

World Heritage Sites and Indigenous Peoples’ RightsEditors: Stefan Disko and Helen TugendhatCover and Layout: Jorge MonrásCover Photos: Bangaan Rice Terraces: Jacques Beaulieu (CC BY-NC 2.0); Uluru:unknown photographer; Ngorongoro Conservation Area: Geneviève Rose (IWGIA)Illustrations: As indicated. Data for the little maps at the beginning of each casestudy provided by IUCN and UNEP-WCMC. 2013. The World Database on ProtectedAreas (WDPA). Cambridge, UNEP-WCMC. www.protectedplanet.netTranslation: Elaine Bolton (Spanish, French); Lindsay Johnstone (French)Proof reading: Elaine BoltonRepress and Print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark The authors, IWGIA, Forest Peoples Programme and Gundjeihmi AboriginalCorporation 2014 – All Rights ReservedDistribution in United States:Transaction PublishersRaritan Center 300 McGaw Drive, Edison, NJ 08837, USAwww.transactionpub.comThe reproduction and distribution of information contained in this book for non-commercial use is welcomeas long as the source is cited. However, the translation of this book or its parts, as well as the reproductionof the book is not allowed without the consent of the copyright holders.The articles reflect the authors’ own views and opinions and not necessarily those of the editors or publishersof this book.HURIDOCS CIP DATATitle: World Heritage Sites and Indigenous Peoples’ RightsEditors: Stefan Disko and Helen TugendhatPlace of publication: Copenhagen, DenmarkPublishers: IWGIA, Forest Peoples Programme, Gundjeihmi Aboriginal CorporationDistributors: Europe: Central Books Ltd. – www.centralbooks.com; Outside Europe: TransactionPublishers – www.transactionpub.com. The title is also available from the publishersDate of publication: November 2014Pages: xxii, 545ISBN: 978-87-92786-54-8ISSN: 0105-4503Language: EnglishBibliography: YesIndex terms: Indigenous Peoples/Human Rights/Environmental Conservation & ProtectionIndex codes: LAW110000/ POL035010/NAT011000Geographical area: World

This book has been produced with financial support from The Christensen Fund andthe Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation.FOREST PEOPLES PROGRAMME1c Fosseway Business Centre, Stratford RoadMoreton-in-Marsh, GL56 9NQ, EnglandTel: 44 (0)1608 652893 – Fax: 44 (0)1608 652878Email: info@forestpeoples.org – Web: www.forestpeoples.orgGUNDJEIHMI ABORIGINAL CORPORATION5 Gregory Place, PO Box 245, Jabiru, Northern Territory, 0886, AustraliaTel: ( 61) 8 89792200 – Fax: ( 61) 8 89792299Email: gundjeihmi@mirarr.net – Web: www.mirarr.netINTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRSClassensgade 11 E, DK-2100 Copenhagen, DenmarkTel: ( 45) 35 27 05 00 – Fax: ( 45) 35 27 05 07Email: iwgia@iwgia.org – Web: www.iwgia.org

ContentsMap of Case Study Locations. xForewordVictoria Tauli-Corpuz, UN Special Rapporteuron the Rights of Indigenous Peoples .xiiPrefaceAnnie Ngalmirama, Chairperson, Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation. xvAcknowledgements.xviiContributors. xviiiPART I – BACKGROUND ARTICLESWorld Heritage Sites and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights: An IntroductionStefan Disko, Helen Tugendhat and Lola García-Alix. 3Indigenous Peoples and Protected Areas: Towards Reconciliation?Marcus Colchester. 39Indigenous Peoples’ Heritage and Human RightsJérémie Gilbert. 55World Heritage, Indigenous Peoples, Communities and Rights: An IUCNPerspectivePeter Bille Larsen, Gonzalo Oviedo and Tim Badman. 65PART II – CASE STUDIESEuropeThe Laponian World Heritage Area: Conflict and Collaboration inSwedish SápmiCarina Green. 85AfricaThe Sangha Trinational World Heritage Site: The Experiencesof Indigenous PeoplesVictor Amougou-Amougou and Olivia Woodburne. 103

‘We are not Taken as People’: Ignoring the Indigenous Identities andHistory of Tsodilo Hills World Heritage Site, BotswanaMichael Taylor. 119Kahuzi-Biega National Park: World Heritage Site versus the Indigenous TwaRoger Muchuba Buhereko. 131Bwindi Impenetrable National Park: The Case of the BatwaChristopher Kidd. 147Ignoring Indigenous Peoples’ Rights: The Case of Lake Bogoria’sDesignation as a UNESCO World Heritage SiteKorir Sing’Oei Abraham. 163A World Heritage Site in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area: Whose World?Whose Heritage?William Olenasha. 189AsiaWestern Ghats of India: A Natural Heritage Enclosure?C.R. Bijoy. 223Indigenous Peoples and Modern Liabilities in the Thung Yai NaresuanWildlife Sanctuary, Thailand: A Conflict over Biocultural DiversityReiner Buergin. 245Shiretoko Natural World Heritage Area and the Ainu PeopleOno Yugo. 269Australia and PacificPukulpa pitjama Ananguku ngurakutu – Welcome to Anangu Land: WorldHeritage at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National ParkMichael Adams. 289No Straight Thing: Experiences of the Mirarr Traditional Owners ofKakadu National Park with the World Heritage ConventionJustin O’Brien. 313Rainforest Aboriginal Peoples and the Wet Tropics of Queensland WorldHeritage Area: The Role of Indigenous Activism in Achieving EffectiveInvolvement in Management and Recognition of the Cultural ValuesHenrietta Marrie and Adrian Marrie. 341The Tangible and Intangible Heritage of Tongariro National Park: A NgātiTūwharetoa Perspective and ReflectionGeorge Asher. 377Rapa Nui National Park, Cultural World Heritage: The Struggle of theRapa Nui People for their Ancestral Territory and Heritage, forEnvironmental Protection, and for Cultural IntegrityErity Teave and Leslie Cloud. 403

North AmericaProtecting Indigenous Rights in Denendeh: The Dehcho First Nationsand Nahanni National Park ReserveLaura Pitkanen and Jonas Antoine. 423The Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Project: A Collaborate Effort ofAnishinaabe First Nations and Two Canadian Provinces to Nominatea World Heritage SiteGord Jones. 441South AmericaA Refuge for People and Biodiversity: The Case of Manu National Park,South-East PeruDaniel Rodriguez and Conrad Feather. 459Canaima National Park and World Heritage Site: Spirit of Evil?Iokiñe Rodríguez. 489‘We Heard the News from the Press’: The Central Suriname Nature Reserveand its Impacts on the Rights of Indigenous and Tribal PeoplesFergus MacKay. 515PART III – APPENDICESAppendix 1African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights Resolution 197on the Protection of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in the Contextof the World Heritage Convention. 528Appendix 2World Conservation Congress Resolution 5.047 on the Implementationof UNDRIP in the Context of the World Heritage Convention. 530Appendix 3Call to Action of the International Expert Workshop on the WorldHeritage Convention and Indigenous Peoples, Copenhagen, 2012. 533Appendix 4Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights ofIndigenous Peoples to the UN General Assembly, 2012 (Excerpt). 539Appendix 5Letter of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights ofIndigenous Peoples to the World Heritage Centre, 2013. 543

Case studyWorld Heritage sites1Laponian Area (Sweden)2Sangha Trinational (Cameroon / Central African Republic / Congo)3Tsodilo (Botswana)4Kahuzi-Biega National Park (Democratic Republic of the Congo)5Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (Uganda)6Kenya Lake System in the Great Rift Valley (Kenya)7Ngorongoro Conservation Area (Tanzania)8Western Ghats (India)9Thungyai-Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuaries (Thailand)10Shiretoko (Japan)

11Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (Australia)12Kakadu National Park (Australia)13Wet Tropics of Queensland (Australia)14Tongariro National Park (New Zealand)15Rapa Nui National Park (Chile)16Nahanni National Park (Canada)17Pimachiowin Aki (Canada)18Manú National Park (Peru)19Canaima National Park (Venezuela)20Central Suriname Nature Reserve (Suriname)

xiiWORLD HERITAGE SITES AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTSForewordVictoria Tauli-Corpuz, UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous PeoplesThe World Heritage Convention (formally the Convention concerning the Protection of the WorldCultural and Natural Heritage) was adopted in 1972 to support the preservation of culturaland natural heritage for the benefit of the world and its peoples. As stated in the Preamble to theConvention, “parts of the cultural or natural heritage are of outstanding interest and therefore needto be preserved as part of the world heritage of mankind as a whole”.The Convention was adopted prior to most of the significant international steps that have beentaken over the past decades to recognize and protect the rights of indigenous peoples, includingthe establishment of several United Nations and regional bodies dedicated to promoting andupholding the rights of indigenous peoples. The Convention therefore does not reference or reflectthese important steps and is, in fact, in some ways at odds with them. Critical among these stepsis the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)by the UN General Assembly in 2007.The challenge therefore presents itself to indigenous peoples to engage with the World HeritageConvention and its organs and States Parties in order to ensure that the implementation of theConvention is amended and improved to take into consideration the new international consensusregarding the importance of recognizing, respecting and protecting the rights of indigenouspeoples. This challenge is particularly urgent given the fact that World Heritage sites can be, andhave often been, declared in areas that incorporate, in part or in whole, the lands, territories andresources of indigenous peoples. The result of this incorporation has not always been positive forindigenous peoples, and has usually come as part of a longer pattern of conservation policies andlaws being applied at the national level.Human rights bodies in the UN system have recognized the violations of the rights of indigenouspeoples that can result from the application of conservation policies and, more specifically, from theimplementation of the World Heritage Convention. All three of the UN mechanisms dedicatedspecifically to promoting the rights of indigenous peoples (the Permanent Forum on IndigenousIssues, the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Special Rapporteur onthe Rights of Indigenous Peoples) have called for reforms in the way in which the Convention isapplied, underlining the urgent need to reform the Operational Guidelines through which theConvention is implemented so that they are aligned with the UNDRIP. They have highlighted theneed to adopt procedures to ensure indigenous peoples’ free, prior and informed consent whensites are inscribed on the World Heritage List, the need to address the frequent lack of access byindigenous peoples to information about pending nominations and other Convention processesaffecting them, and the need to take measures to ensure the protection of indigenous peoples’

FOREWORDxiiilivelihoods and tangible and intangible cultural heritage in World Heritage areas, among manyother issues.My predecessor as Special Rapporteur, James Anaya, dedicated a whole section of his 2012report to the UN General Assembly to the recurring issue of the impact of World Heritage sites onindigenous peoples, which contains a range of observations and recommendations on measuresto prevent and remedy violations of indigenous rights in the implementation of the World HeritageConvention. Additional recommendations are contained in a communication he sent to the WorldHeritage Centre on 18 November 2013. I intend to follow-up these recommendations during thecourse of my mandate as Special Rapporteur.It is clear that there is widespread recognition among human rights bodies of the legacy ofproblems in the implementation of the World Heritage Convention and the impacts that this has hadon indigenous peoples. I therefore want to add my support to an important 2012 recommendationof the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which states: “The ExpertMechanism encourages the World Heritage Committee to establish a process to elaborate, withthe full and effective participation of indigenous peoples, changes to the current procedures andoperational guidelines and other appropriate measures to ensure that the implementation of theWorld Heritage Convention is consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights ofIndigenous Peoples and that indigenous peoples can effectively participate in the World HeritageConvention’s decision-making processes.”The members of the Expert Mechanism highlighted both the importance of the UN Declarationon the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a guide in implementing other conventions or treaties, andthe importance of full and effective participation of indigenous peoples in decision-making thataffects them, both themes that are explored at length in this book and which are fundamental toempowering indigenous peoples to guide their own development.This book provides detailed case studies exploring the history and continued development andmanagement of World Heritage sites that incorporate, in whole or in part, the lands, territories andresources of indigenous peoples. The testimonies and histories recorded in this book reveal someof the key challenges facing States and the World Heritage Convention bodies in ensuring that theimplementation of the Convention does, in fact, support the aspirations of indigenous peoples tosee their rights recognized and respected. The testimonies also reveal the hard work done byindigenous peoples in fighting for respect for their rights in World Heritage areas, through directadvocacy with the World Heritage Committee, engagement with international and/or regionalhuman rights bodies, and national level efforts to achieve self-determination over their lands,territories and resources and their economic, social and cultural development as distinct peoples.The stories contained herein reflect both the potential for the World Heritage Convention tosupport the self-determined development of indigenous peoples by helping them to preventnegative developments in their territories, and the difficulties inherent in the implementation of aConvention that does not explicitly recognize the rights of the peoples on which it has a directimpact. I hope that this book will form a contribution to increasing the respect between the WorldHeritage Convention and the rights of the indigenous peoples living in or around the natural,cultural and mixed sites protected under the Convention.

xivWORLD HERITAGE SITES AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTSIn accordance with Human Rights Council resolution 15/14 of 2010, core aspects of mymandate as Special Rapporteur are examining ways and means of overcoming existing obstaclesto the full and effective protection of the rights of indigenous peoples; formulating recommendationsand proposals on appropriate measures and activities to prevent and remedy violations of therights of indigenous peoples; and developing a regular cooperative dialogue with all relevantactors, including Governments, relevant United Nations bodies, specialized agencies andprogrammes. As Special Rapporteur, I look forward to engaging with all the agencies and bodiesinvolved in the implementation of the World Heritage Convention to improve its record with indigenouspeoples, and to supporting indigenous peoples in the protection of their own heritage.

xvPrefaceAnnie Ngalmirama, Chairperson, Gundjeihmi Aboriginal CorporationSince the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, agreat deal of attention has been paid to respecting the rights of Indigenous peoples in theimplementation of the World Heritage Convention. During the Convention’s 40th anniversary in2012 (officially celebrated under the theme of “World Heritage and Sustainable Development: theRole of Local Communities”), the need to improve protection of indigenous peoples’ rights in WorldHeritage sites was often talked about. For the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, which representsthe Mirarr Aboriginal people, this issue is very important as part of our country lies within KakaduNational Park, which has been listed as a World Heritage site for over thirty years.Kakadu is many things to many people. It is World Heritage, it is a national park; it is whereuranium mining occurs. For us Mirarr and other local Aboriginal people (Bininj), it is home. It is ourancient and long-lasting home. Our word for our land is Gunred. Gunred sustains us and wesustain it. We are obliged to care for it and for those who visit it. We do not see ourselves asseparate to our land. Our land exists through us and we exist through it.For many years, Kakadu has been a place where the Australian government and we Bininjhave worked, lived and argued together. We Bininj are proud of our home and of its World Heritagerecognition. For over thirty years, Mirarr have worked to protect our home against unwanteduranium mining and sometimes against the government’s way of managing our land. Sometimes,we are at one with the government; at other times, we are in strong disagreement. We have alsoresorted to open protest and, to stop the proposed Jabiluka uranium mine, campaigned here inKakadu and across Australia and the world. In the end we prevailed and mining at Jabiluka wasstopped.We have learned much along this journey with the Australian Government and the UNESCOWorld Heritage Committee. Kakadu’s World Heritage status has helped us to prevail, by drawinginternational attention to our disagreements with the government. We have learned much aboutwhat we believe to be the denial of our fundamental international human rights because of miningand the way the Park has been managed.We have also had positive experiences with the government. Over the years we have developedclose working relationships and friendships with park rangers and other government staff. Theyhave often helped us manage our land and they have been there during trying times. In recentyears, we have also worked alongside the Djok clan and the government in partnership to secureWorld Heritage recognition of the Koongarra area.Our journey with the government and the World Heritage Committee has had many twists andturns and, at the end of the day, it is an ongoing journey. We have been given great hope in recent

xviWORLD HERITAGE SITES AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTStimes that our relationships with both government and industry are increasingly on a more respectfulbasis, that more opportunities for Bininj people are possible. Much of this is due to Kakadu’s WorldHeritage status. It helps keep an international focus on our home and our relationships.We stand in solidarity with other Indigenous peoples in World Heritage areas across the worldand trust that their respective governments, UNESCO, and the international community willgenuinely and effectively include these peoples in all their decision-making and benefit-sharing.We hope that this book will be a useful contribution to that end.

xviiAcknowledgementsThe editors of this book are grateful to the many people who supported or contributed to itssuccessful production in one way or another. Our warmest appreciation and thanks go toLola García-Alix who, in her capacity as IWGIA’s Executive Director, guided us and supported uswherever she could throughout the production of the book and without whom this project wouldcertainly not have been possible.In addition to the authors who contributed book chapters and to whom we are most grateful,we would like to express our sincere acknowledgement and appreciation of those who submittedor helped with chapters which, in the end, could not be included. We are also grateful to those whoreviewed chapters for us, provided comments or helped in finding authors.We would further like to express our gratitude for the financial support received from TheChristensen Fund and the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation for the production of this book.Finally, it is important for us to thank our families for their continuous personal support, patienceand encouragement.Although it is not easy to separate out those who deserve special mention in a project thatbenefited from the work and efforts of so many, we would like to acknowledge the followingindividuals: Justin O’Brien, Mililani Trask, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, Annie Ngalmirama, YvonneMargarula, Mattias Åhrén, Lars-Anders Baer, Carol Sørensen, Wilson Kipkazi, Lucy Claridge, AlbertBarume, Merrilyn Wasson, Bruce White, Ashish Kothari, Chris Erni, Ann-Elise Lewallen, Max Ooft,Donato Bitog, Jill Carino, Alexandra Bocharnikova, Johannes Rohr, Ndukuyakhe Ndlovu, DianaVinding, Robert Hitchcock, Christian Strobl, Aliya Ryan, Kathrin Wessendorf, Cæcilie Mikkelsen,Annette Kjærgaard, Marianne Wiben Jensen, Alejandro Parellada, Suzanne Jasper, Dalee SamboDorough, Mechtild Rössler, Patricia Borraz, June Lorenzo, Ida Nicolaisen, James Tugendhat, andCaroline Maciel Lauar.Stefan Disko and Helen TugendhatOctober 2014

xviiiWORLD HERITAGE SITES AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTSContributorsMichael Adams is Associate Professor of Geography at the University of Wollongong. He is amember of the Indigenous Peoples’ Knowledges and Rights Commission of the InternationalGeographical Union, and a member of two commissions of IUCN. His research focus has been onthe relationship between Indigenous peoples and Protected Areas.Victor Amougou-Amougou began work in rural development, helping with the capacity building offarmers’ associations and cooperatives. Since 2001 he has worked primarily on Indigenous peoples’rights and livelihoods, through issues such as forestry, land and natural resource management,and has conducted detailed participatory mapping of resource use in protected areas. He is cofounder and coordinator of CEFAID (Centre pour l’Education, la Formation et l’Appui aux Initiativesde Développement au Cameroun), a local NGO with extensive CSO networks throughout theCongo Basin.Jonas Antoine is a Dehcho Dene Elder from Liidlii Kue First Nation. Jonas was a member ofthe Nahanni Expansion Working Group, is a member of the Naha Dehe Consensus Team andrepresents the Dehcho First Nations in other protected areas initiatives in the Dehcho Process.George Asher is of Maori descent and Chief Executive Officer of the Lake Taupo and LakeRotoaira Forest Trusts in New Zealand. Both trusts comprise 55,000 hectares of ancestral lands ofwhich 33,000 hectares are planted with commercial production forests. Parts of these lands adjoinTongariro National Park and have been protected in their natural state. George has been activelyinvolved in the development of his tribe, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, for the past 30 years and was alsoindependent advisor to the 2006-07 Chairperson of the World Heritage Committee.Tim Badman is Director of the World Heritage Programme at the International Union forConservation of Nature (IUCN), with responsibility for managing IUCN’s official advisory role tothe UNESCO World Heritage Committee, and developing IUCN’s wider activities related to WorldHeritage.C.R. Bijoy is an independent researcher-activist who is primarily involved in indigenous peoples’struggles, for instance with the Campaign for Survival and Dignity, a national coalition of Adivasiand forest dweller organisations.Reiner Buergin is an anthropologist with a background in forestry. He has carried out extensivefield research in the Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary, studying problems of local change andland use in the context of national forest policies and international environmentalism.

CONTRIBUTORSxixLeslie Cloud is a researcher in public law, legal anthropology and indigenous peoples’ rights. Sheis currently undertaking a PhD in public law on the recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples inChile and is working in on the SOGIP (Scales of Governance: The UN, the States and IndigenousPeoples) project, funded by the European Research Council (ERC 249236) and based at the Écoledes Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris.Marcus Colchester received his doctorate in social anthropology from the University of Oxfordand has carried out extensive field research in applied anthropology, mainly in Amazonia, Southand South-East Asia. His human rights advocacy related to development and conservation hasearned him a Pew Conservation Fellowship and the Royal Anthropological Institute’s Lucy MairMedal for Applied Anthropology. He is a founder member of the World Rainforest Movement andwas for many years the Director of the Forest Peoples Programme, where he now acts as SeniorPolicy Advisor. He has published extensively and is the author and editor of numerous books onforests, biodiversity and human rights.Stefan Disko holds an M.A. in Ethnology, American Cultural History and International Lawfrom the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich and an M.A. in World Heritage Studies from theBrandenburg University of Technology. Since 2000, his professional life has focused on workingwith indigenous organisations on human rights issues, mostly in the context of the United Nations.He has published various articles and reports on World Heritage and indigenous peoples’ rights.Conrad Feather is an anthropologist (PhD, University of St Andrews, UK) who has worked withindigenous peoples in south-east Peru since 2000 and is now working for the Forest PeoplesProgramme as a Project Officer.Lola García-Alix holds an M.A. in Sociology from the Complutense University of Madrid. She hasworked at IWGIA since 1990 and has held a variety of positions within the organisation. From 1993until 2006 she served as Coordinator of the International Human Rights Advocacy Program. In2004, she was appointed Vice-Director by IWGIA’s Board and, in 2007, Executive Director. SinceSeptember 2014 she has resumed her position overseeing IWGIA’s International Human RightsAdvocacy work.Jérémie Gilbert is a Reader in Law at the University of East London. He has published variousbooks and articles on the rights of indigenous peoples, in particular on territorial rights, with hislatest being Nomadic Peoples and Human Rights (Routledge, 2014). Jérémie often works withindigenous communities and NGOs on cases involving land rights. As a legal expert he hasbeen involved in providing legal briefs, opinions and carrying out evidence gathering in severalcases involving indigenous peoples’ land rights, especially in Africa. He is a member of IWGIA’sinternational board, a member of Minority Rights Group International’s Advisory Board on theLegal Cases Programme and also regularly works with the Forest Peoples Programme and theRainforest Foundation.

xxWORLD HERITAGE SITES AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTSCarina Green holds a PhD in Cultural Anthropology from Uppsala University. Her research focuseson indigenous peoples and ethno-political mobilization. Her doctoral thesis approached the processof implementing a management plan in the Laponian World Heritage Area in Sweden. She has alsocarried out fieldwork in Australia and New Zealand on indigenous influence over World Heritagemanagement and on the relationship between indigenous groups and environmental a

World Heritage Convention is consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and that indigenous peoples can effectively participate in the World Heritage Convention's decision-making processes." The members of the Expert Mechanism highlighted both the importance of the