Transcription

Making WICWork Better:Strategies to Reach More Womenand Children and StrengthenBenefits UseMay 2019Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternMay 2019nnwww.FRAC.orgwww.FRAC.org1

Making WIC Work Better:Strategies to Reach More Women and Childrenand Strengthen Benefits UseAcknowledgmentsThe Food Research & Action Center (FRAC) is grateful forthe support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation indeveloping and launching this project to improve the reachand impact of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Programfor Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).This report was written by FRAC’s Director of NutritionPolicy and Early Childhood Nutrition Programs,Geraldine Henchy.Special thanks go to 1,000 Days for their partnership.We would also like to thank Jamie Bussel, SeniorProgram Officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation,for her guidance and counsel with this project. FRACappreciates Imani Marshall and Tina Tran, formerFRAC Emerson Hunger Fellows, for their meaningfulcontributions to the multi-year research project. FRACis grateful to the many stakeholders who shared theirexperiences and insights through interviews, surveys,meetings, and group discussions.About the Food Research& Action CenterThe Food Research & Action Center is the leading nationalorganization working for more effective public and privatepolicies to eradicate domestic hunger and undernutrition.For more information, go to: frac.org.The findings and conclusions presented in this reportare those of FRAC alone.Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternMay 2019nwww.FRAC.org2

IntroductionThe Special Supplemental Nutrition Program forWomen, Infants, and Children (WIC) is a federalfood program that provides low-incomenutritionally at-risk pregnant women, postpartummothers, infants, and children up to 5 years old withnutritious foods, nutrition education, breastfeedingsupport, and referrals to health care.Protecting and improving the health of pregnantand postpartum women, infants, and young childrenis critically important. Those eligible for WIC — andfrequently their communities and the nation — arefacing levels of poverty, food insecurity, inadequatedietary intake, obesity, and ill health that are far toohigh. Research shows that WIC can help to alleviatethese problems for children, mothers, and theirfamilies, and improve overall health and well-being.Yet the program is reaching far too few eligiblepeople: only 3 out of 5. Increasing access to andstrengthening WIC is essential to improving nutritionand reducing health disparities in this nation.Many eligible families not participating in WIC facesignificant barriers to reaching the much-neededbenefits WIC offers. Barriers to WIC include:nnnlanguage and cultural barriers;nnegative clinic experiences (such as long waittimes or poor customer service);nloss of time away from work (creating job risk andlost wages) to apply and maintain eligibility;ndissatisfaction with the contents of the children’sfood package; andndifficulty redeeming benefits (limited selection ofWIC foods available and embarrassing check-outexperiences).common misconceptions about who is or is noteligible (particularly misunderstandings about theeligibility of low-wage working families, immigrantfamilies, and children ages 1 to 5 years old);These factors impact decisions to enroll andcontinue to participate in WIC.transportation and other costs to reach WIC clinicsto apply and continue to receive counseling andbenefits;For all stakeholders, including WIC clinics,community-serving organizations, anti-hungergroups, other advocates, health care providers,Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternMay 2019nwww.FRAC.org3

Head Start, grocery stores, and other partners— there are proven and innovative strategies toeffectively reach and serve more of those whoare eligible, including a culturally and linguisticallydiverse population, and a new generation oftechnologically savvy mothers.This publication provides an extensive menu ofstrategies, including featured spotlight programs, toimprove the reach of WIC and benefit use. You willfind the information needed to understand barriers toparticipation, identify strategies appropriate to yourstate, community, or program, and make the casefor WIC. Presented in non-technical language, thispublication is intended to be understandable forall stakeholders from the novice to the expert.The recommended strategies focus on the followingkey areas:nWIC Outreach and Promotion;WIC Partnerships: Communication, Coordination,and Referrals;nThe WIC Clinic Experience;nReaching and Serving Special Populations;nTechnology — Modernizing WIC;nNutrition Education — A Valuable Asset for WICFamilies;nWIC Retention and Recruitment of FamiliesWith Children 1 to 4 Years Old;nOptimizing the WIC Shopping Experience;nSupport from Federal, State, and LocalGovernments; andnWIC in Disasters.nMaking WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternThese recommendations are based on the FoodResearch & Action Center’s Robert Wood JohnsonFoundation-funded multi-year investigation of thebarriers to WIC participation and benefits, andeffective strategies for maximizing WIC participationand the utilization of benefits. The Food Research& Action Center conducted a comprehensivebackground research and literature review; an indepth analysis of WIC participation, WIC coverage,and related factors; a WIC survey; and interviewsand discussions with national, state, and localstakeholders, including WIC and Indian TribalOrganization directors, anti-hunger, health, andnutrition advocates, grocery store representatives,early care and education leaders and programoperators, and policy makers.May 2019nwww.FRAC.org4

Table of ContentsPart 1: The WIC Program: Basics and Benefits for Participants and Communities6Part 2: WIC Participants, Program Trends, Coverage, and Barriers11Part 3: WIC Recommendations and Strategies16Section 1: WIC Outreach and Promotion17Section 2: WIC Partnerships: Communication, Coordination, and Referrals22Section 3: The WIC Clinic Experience33Section 4: Reaching and Serving Special Populations39Section 5: Technology — Modernizing WIC48Section 6: Nutrition Education — A Valuable Asset for WIC Families53Section 7: WIC Retention and Recruitment of Families WithChildren 1 to 4 Years Old58Section 8: Optimizing the WIC Shopping Experience63Section 9: Support From Federal, State, and Local Governments67Section 10: WIC in Disasters70Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternMay 2019nwww.FRAC.org5

Part 1: The WIC Program: Basics andBenefits for Participants andCommunitiesThe Special Supplemental Nutrition Program forWomen, Infants, and Children (WIC), a federal nutritionprogram, is widely recognized as an importantsafeguard for protecting and improving the health andnutrition of low-income mothers and children. Poor nutrition,poverty, and food insecurity have detrimental impacts oninfant, child, and maternal health and well-being in the shortand long terms.1 One critical strategy to address theseissues is connecting vulnerable families to the multi-facetedbenefits of WIC, and assuring the use of the benefit packageis maximized.WIC provides low-income pregnant women, postpartummothers, infants, and children up to 5 years old withnutritious foods, nutrition education and counseling, andreferrals to health care and social services.2 Women, infants,and children are eligible for the program if they meet thestatutory income guidelines (i.e., at or below 185 percentof the federal poverty line), or are deemed income-eligiblebased on participation in other programs, such as Medicaid,the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), orTemporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). In additionto being income-eligible, applicants must be at nutritionalrisk (e.g., underweight, overweight, anemic, have poordietary intake) as determined through a nutrition assessmentconducted by a health professional.WIC is federally funded through the U.S. Department ofAgriculture (USDA) and is operated through local clinics bystate WIC agencies and Indian Nations. Food packagesare prescribed to WIC participants based on their specificnutritional needs and include a variety of foods intended tosupplement their diets, not to be a full diet. WIC-authorizedfoods include fruits and vegetables, milk, soy milk, yogurt,cheese, tofu, eggs, vitamin C-rich juice, iron-fortified cereal,tuna, peanut butter, beans, whole-grain bread, tortillas, andrice, as well as infant formula, baby food, and infant cereal.The fruits and vegetables, whole-grain bread, and culturalfood options (tortillas, rice, soy milk, and tofu) were added tothe WIC food package in 2009 as part of an overhaul andimprovement of the food package, but the option to offeryogurt was not added until 2015.Local WIC agencies distribute monthly WIC food packagebenefits to participants by providing a WIC electronicbenefits transfer (EBT) card (smart card) or as a set ofpaper WIC food vouchers (checks). (States are requiredto complete the transition from vouchers to EBT cards by2020.) Participants use the vouchers or EBT card to shopfor WIC foods at authorized grocery stores and other WICapproved vendors. WIC guarantees a specific amountof each WIC food, with the exception of the fruits andvegetables benefit, which has a cash value. For example,participants receive a voucher for one dozen eggs, whilethe fruit and vegetable voucher will allow the participant to“purchase” 11 of fruits and vegetables for women and 9for children per month.** There also is a federally funded WIC Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program that provides some WIC participants additional coupons to use atfarmers’ markets in the summer.Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternMay 2019nwww.FRAC.org6

n Nationally, WIC lifted 279,000 people above the povertyWIC Improves Health and Well-Being,Family Food Security and EconomicSecurity, and the Availability of HealthyFoods in Low-Income Communitiesline in 2017, based on Census Bureau data on poverty andincome in the U.S.6n Families receiving housing subsidies, SNAP, and WICbenefits were 72 percent more likely to be housingsecure compared to those families receiving housingsubsidies alone, based on a study of low-incomecaregivers of children younger than 3 years old.7(Housing-secure is defined as living without overcrowdingor frequent moves within the last year.)A very large body of research shows that WIC is aprofoundly important program with well-documentedbenefits for infants, children, pregnant women, and theirfamilies. Research shows that WIC improves participants’health and well-being, dietary intake, and birth andhealth outcomes; protects against obesity; and supportslearning and development. WIC benefits are cost-effective,generating major savings in federal, state, local, and privatehealth care, as well as special education costs.3 Studiesdemonstrate that WIC improves food and economic securityof participants by reducing food insecurity, helping toalleviate poverty, and supporting economic stability.n WIC, along with other social safety net programs, is abuffer against the harmful impacts of economic hardshipand responsive to increased need during economicdownturns. For example, program participation increasedamong eligible children before and during the GreatRecession.8WIC also can be a powerful tool in creating healthier, moreequitable communities. WIC has the potential to improve theavailability of healthy foods in low-income communities for allshoppers. The WIC food package improves the variety andavailability of healthy foods in WIC and, in some cases, nonWIC food stores. In addition to improving the dietary intakeand health of participants, WIC interjects much-neededfunds into a community’s food economy.more nutrient-rich and lower in calories from solid fatsand added sugars than the diets of income-eligiblenonparticipants.12n Compared to low-income nonparticipants, young childrenn WIC reduces the prevalence of household food insecurityin recipient households with children under 5 years old byat least 20 percent.4n Pregnant women experiencing household food insecuritywith hunger who enroll in WIC in the first or secondtrimester (versus the third trimester) have a reduced riskof any food insecurity post-partum.5Food Research & Action Centern WIC participation is associated with better dietary intaken The overall diets of young children enrolled in WIC areWIC Improves Household EconomicSecurity, Reduces Food Insecurity,Alleviates Poverty, and SupportsEconomic StabilitynWIC Improves Dietary Intakeand overall dietary quality, including increased irondensity of the diet, increased consumption of fruits andvegetables, greater variety of foods consumed, andreduced added sugar intake.9,10,11The following selection of studies highlights some of theresearch demonstrating WIC’s effective role in helping toimprove food and economic security, health and well-being,and retail environments.Making WIC Work BetterWIC Improves Health and Well-Being:Improves Dietary Intake, Birth and HealthOutcomes, Protects Against Obesity, andSupports Learning and Developmentnparticipating in SNAP, WIC, or both programs have lowerrates of anemia and nutritional deficiency.13n Multiple studies link the revised WIC food packages withimprovements in overall dietary quality, healthful foodpurchases, and the consumption of fruits, vegetables,whole-grain foods, and lower-fat milk.14,15 Research alsofinds improvements in infant feeding practices in termsof the appropriate introduction of solid foods, as well asincreases in breastfeeding initiation.May 2019nwww.FRAC.org7

WIC Improves Birth OutcomesWIC Improves Health Outcomesn WIC enrollment and greater WIC food package utilizationn Low-income children who currently participate in WICduring pregnancy are associated with improved birthoutcomes, including lower risk of preterm birth, low birthweight, being small for gestational age, and perinataldeath.16,17have immunization rates that are comparable to higherincome children who are ineligible for the program(e.g., 94 and 92 percent, respectively, for the measlesvaccination), whereas low-income children who neverparticipated in the program have the lowest vaccinationrates (e.g., 83 percent for the measles vaccination).22n A study in South Carolina found that WIC participation isassociated with an increase in birth weight and lengthof gestation, as well as a lower probability of low birthweight, preterm birth, and neonatal intensive careunit admission.18 In this study, the positive effects ofparticipation were larger for African-American mothers.n Prenatal WIC participation is associated with increasedinfant health care utilization in the first year of life, in termsof increased well-child visits and vaccinations, basedon a study using South Carolina Medicaid claims data.23Prenatal WIC participation also is linked to decreases inthe average number of days an infant is hospitalized inthe first year of life.n Prenatal WIC participation is associated with lowerinfant mortality rates, especially for African-Americans.19Similarly, WIC participation is associated with lower oddsof stillbirth among African-American women.20n Young children participating in SNAP, WIC, or bothn Based on administrative data in Missouri and Oklahoma,mothers who receive WIC during pregnancy are morelikely to breastfeed their infant at hospital discharge thannonparticipants. In addition, fee-for-service Medicaid costsfrom birth through 60 days postpartum are significantlylower for WIC participants in Missouri ( 6,676 for WICparticipants versus 7,256 for similar nonparticipants).21programs have lower rates of failure to thrive and lowerrisk of abuse and neglect, when compared to low-incomenonparticipants.24n Even in the face of family stressors, such as householdfood insecurity and maternal depressive symptoms,children who receive WIC, compared to those who donot, are less likely to be in fair or poor health and morelikely to meet well-child criteria.25 (For this particular study,children met “well-child” criteria if they were in goodor excellent health per parent report, were developingnormally, were not overweight or underweight, and hadnot been hospitalized.)n When compared to their non-WIC siblings, children whosemothers participate in WIC during the prenatal periodare less likely to be diagnosed with attention deficithyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and less likely to have amoderate-to-severe infection as of 6–11 years of age.26WIC Protects Against Obesityn A study set in eight New York City-area primary carepractices found that food insecurity was significantlyassociated with increased body mass index only amongthose women who were not receiving food assistance(SNAP or WIC), suggesting that food assistance programparticipation plays a protective role against obesityamong food-insecure women.27Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternMay 2019nwww.FRAC.org8

n A growing body of evidence suggests that the WIC foodWIC Improves Neighborhood FoodEnvironments, Increasing the Availabilityof Healthy Foods in Low-IncomeCommunitiespackage revisions are associated with favorable impactson the prevalence of obesity among young children.28, 29For example, in a study using data from 2000 through2014, obesity rates among 2- to 4-year-old WICparticipants were increasing by 0.23 percentage pointsper year before the 2009 revisions, but obesity ratesdeclined by 0.34 percentage points per year after therevisions.30n After the introduction of the new WIC food packagesin 2009, improvements in healthy food availabilitywere observed in WIC-authorized stores and non-WICstores in a number of studies using composite scores ofavailability.36, 37, 38n Other research suggests that WIC may protect againstobesity among young children in families facing multiplestressors (e.g., household food insecurity and caregiverdepressive symptoms).31For example, among 252 convenience stores and nonchain grocery stores in five Connecticut towns, access tohealthy foods improved both in WIC-authorized and, to alesser extent, in non-WIC stores.39 Changes in this studywere evaluated through a Healthy Food Supply Score thataccounted for the availability, variety, quality, and pricesof foods included in the new packages. Improvements inscores were more pronounced for WIC-authorized stores,especially those in lower-income areas, and were drivenprimarily by the greater availability and variety of wholegrain products.n In a small sample of preschoolers, children in householdsreceiving WIC benefits weighed significantly less andhad lower LDL (“bad”) cholesterol levels than childrenfrom nonparticipating households.32 The study’s authorsconclude that the results “indicate WIC may be a pieceof public health efforts to combat the childhood obesityepidemic and reduce other cardiovascular risk factors,such as blood lipids and blood pressure.”WIC Supports Learning and Developmentn Another study set in 45 corner stores in Hartford,Connecticut, found that WIC-certified stores offered morevarieties of fresh fruits, a greater proportion of lower-fatmilk, and greater availability of whole-grain productsafter the introduction of the new WIC food packages,compared to those stores without WIC authorization.40n Children whose mothers participate in WIC during theprenatal period are less likely to repeat a grade later inchildhood compared to their non-WIC siblings.33n Maternal participation in WIC has a strong and directeffect on early childhood language development,especially for receptive communication outcomes (e.g.,pointing to common objects or pictures of actions in apicture book).34n Among 27 small WIC stores in New Orleans, theavailability of whole wheat bread and brown rice, andthe variety of fresh fruits significantly increased afterthe introduction of the new WIC food packages.41 Freshfruits and brown rice availability also both significantlyincreased among 66 small, non-WIC stores after the WICpackages were revised. WIC stores, on average, hadlarger improvements in the number of fresh fruit varieties,as well as in shelf space dedicated to vegetablescompared to non-WIC stores.n Prenatal and early childhood participation in WICis associated with stronger cognitive developmentat 2 years old, and better performance on readingassessments in elementary school, leading researchersto conclude that “these findings suggest that WICmeaningfully contributes to children’s educationalprospects.”35n In a study of 105 WIC-approved stores in Texas,For additional information on the effectiveness of WIC,see the Food Research & Action Center’s WIC is aCritical Economic, Nutrition, and Health Support forChildren and Families.Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action Centerresearchers observed an increase in shelf spaceavailability for most key healthy food options (e.g., fruits,vegetables, and cereal) and greater visibility of freshjuices after the WIC food package revisions.42 The studynMay 2019nwww.FRAC.org9

WIC’s four-and-a-half decades of history is one of the greataccomplishments in improving nutrition and health. Studyafter study has found huge benefits of WIC participation.Yet the program is reaching far too few eligible people.also found improvements in WIC labeling visibility forfruits, WIC-approved cereal, and whole-grain or wholewheat bread.n According to a study of 118 food stores in Baltimore,Maryland, healthy food availability (e.g., fruits, vegetables)improved significantly between 2006 and 2012. Theseimpacts were most pronounced in corner stores andpredominantly Black census tracts.43The WIC Program:n In a study examining fruit and vegetable prices inmore than 300 WIC-authorized stores in seven Illinoiscounties, overall prices fell for canned vegetables andfrozen vegetables after the WIC food package revisionswere implemented, possibly from greater demand andeconomies of scale.44 The largest price reductions wereobserved for canned fruits and frozen vegetables in smallstores, and frozen vegetables in non-chain supermarkets.Chain supermarkets also had modest reductions in theprices of fresh vegetables and frozen fruits. According toanother study using the same sample of Illinois stores,the overall availability improved in stores for commonlyconsumed fresh fruits and vegetables, fresh fruits andvegetables commonly consumed by African-Americanfamilies, canned low-sodium vegetables, and frozen fruitsand vegetables.45nreduces food insecurity;nalleviates poverty;nsupports economic stability;nimproves dietary intake;nprotects against obesity;nimproves birth outcomes;nimproves health outcomes;nsupports learning and development;nreduces health care and other costs; andnimproves retail food environments.n WIC-authorized food retailers across the nation reportincreased demand for and sales of healthy foods includedin the new WIC food packages, especially fresh produce,whole-grain products, and lower-fat milk.46, 47, 48 Many alsoconclude that the introduction of the new food packageshas improved their stores, and increased their customersand profits.For more research on the food packages, see the FoodResearch & Action Center’s Impact of the Revised WICFood Packages on Nutrition Outcomes and the RetailFood Environment.Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternMay 2019nwww.FRAC.org10

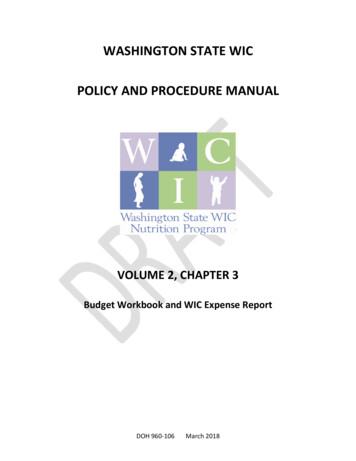

Part 2: WIC Participants, Program Trends,Coverage, and BarriersWIC ParticipantsWIC provided services to approximately 6.9 million people— 1.6 million women, 1.7 million infants, and 3.5 millionchildren — in an average month in federal fiscal year 2018.49Almost half of all infants born in the U.S. benefit from the WICprogram.50WIC plays an important role in creating health equity. WICserves some of the nation’s most vulnerable households,providing them with the means and opportunities to makechoices that can help them lead the healthiest lives possible.Almost two-thirds (65.6 percent) of all WIC participants haveincomes at or below the federal poverty level.51 Nearly onethird (32.5 percent) of WIC participants have incomes equalto or less than 50 percent of the federal poverty level.52WIC serves an ethnically and racially diverse population.Many WIC participants (41.8 percent) are Hispanic orLatino.53* Slightly over 10 percent (10.3 percent) of WICparticipants are American Indian or Alaskan Native, 4.4percent are Asian or Pacific Islander, 20.8 percent are Blackor African-American, and 58.6 percent are White.54 Acrossracial and ethnic groups, average annual household incomewas lowest for Black or African-American postpartumwomen participating in WIC ( 12,080).55high of 9.2 million in fiscal year 2010.57 Improving economicconditions that meant fewer women and children wereeligible, and declining birth rates explain some of this declinein participation. But the decline also reflects, in part, a dropin the share of eligible women and children who are actuallyparticipating. According to USDA’s most recent coveragereport, WIC has been serving a considerably smallerproportion of those eligible: 54.5 percent in 2016 comparedto 63.5 percent in 2010.58WIC Coverage Rates for Eligible PeopleIn the latest year (2016) for which USDA has publishedcoverage-rate data, WIC served only 54.5 percent of thosewho are eligible.59 The overall coverage rate is the number ofpeople receiving WIC benefits compared to the total number ofpeople eligible for WIC. Typical of long-term WIC participationpatterns, the program has the highest coverage rates forinfants, lower coverage rates for women, and the lowestcoverage rates for children ages 1 to 4 years old. In 2016:n The WIC program served an estimated 85.9 percent ofeligible infants and just 44.1 percent of eligible childrenages 1 to 5 years old.n For most of the infants in WIC, their mothers participatedin WIC during pregnancy, enrolling in the first (53.8percent), second (36.6 percent), or third trimester (9.4percent). The reported WIC coverage rate for eligiblepregnant women, 50.3 percent, is calculated by usingadjustments that account for factors related to womenparticipating for all three trimesters.Federal food program costs for WIC totaled 5.4 billion infiscal year 2018: 3.4 billion was expended on food benefitsfor participants, and nearly 2 billion for nutrition servicesand administration.56WIC Participation Trendsn WIC served 62.2 percent of eligible breastfeedingIn fiscal year 2018, WIC served an average of approximately6.9 million participants each month, down 23 percent from apostpartum women and an estimated 100 percent ofnon-breastfeeding postpartum women.* Ethnicity, Hispanic/Latino or Non-Hispanic/Latino, is reported separately from race.Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternMay 2019nwww.FRAC.org11

50 percent or lower in 20 states to a high of 65.6 percentin California.61 For children ages 1 to 4 years old, the statecoverage rates are even lower, as low as 30.2 percent, withcoverage rates below 50 percent in 46 states. The highestcoverage rates for children are in California (57.2 percent)and Vermont (61.2 percent). According to USDA, almost allof the states follow the national pattern of having the highestcoverage rates for infants, lower coverage rates for women,and the lowest coverage rates for children.62n The 2016 coverage rates for infants (85.9 percent) andnon-breastfeeding postpartum women (100 percent) arehigher than expected. USDA noted that the numbers maybe inflated due to a census undercount of WIC eligibleinfants, but it will take another year of data to confirm thatsupposition.60*Coverage rates vary significantly by state.* The overallcoverage rate in the most recent data, 2016, varies fromWIC Coverage Rates for Total Eligible Individuals by State, 2016 WA: 55.0%MT: 38.2%ND: 50.1%MN: 60.3%ME:52.9%WI: 48.5%SD: 48.7%OR: 56.3%ID: 43.4%WY: 53.9%UT: 39.4%NY: 55.9%IA: 46.8%2 Hudson River, NYNE: 52.8%3 Upper Mississippi River, IL, IA, MO4 Green-Duwamish River, WANV: 55.2%CO: 43.5%5 Willamette River, ORKS: 52.0%6 Chilkat River, AKIN:IL: 45.1% 51.4%AZ: 50.3%WV:50.3%KY: 53.3%8 Buffalo National River, AROK: 55.0%AR: 49.3%9 Big Darby Creek, OHNM: 44.8%10 Stikine River, AKTX: 57.5%LA:52.0%PA: 51.6%OH: 51.3%MO: 50.8%7 South Fork Salmon River, IDCA: 65.6%VT: 55.0%NH: 46.9%MA: 55.2%MI: 55.9%1 Gila River, NMVA:47.8%NC: 53.8%TN: 43.0%MS:51.7%1AL:56.5%RI: 62.2%CT: 49.2%NJ: 53.8%DE: 52.3%MD: 68.3%DC: 54.0%GA:48.2%SC:46.4%FL:53.8 AK: 43.5%HI: 53.4%Less than 40%40%–50%50%–60%60%–70%Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, National- and State-Level Estimates of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)Eligibles and Program Reach in 2016 (Published 2019)* National- and State-Level Estimates of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Eligibles and ProgramReach in 2016: “this may be a single-year anomaly in the estimate of eligible infants due to small sample sizes in the underlying Census data.”and “Another year of estimates is needed to confirm a declining trend in WIC eligibility among infants.” The estimate of eligible infants is alsoused to make the estimates of eligible postpartum women.Making WIC Work BetternFood Research & Action CenternMay 2019nwww.FRAC.org12

WIC Coverage Rates for Children (1 to 4 Years) by State, 2016 WA: 48.9%MT: 30.2%ND: 44.8%MN: 53.2%ME:42.4%WI: 40.5%SD: 45.2%OR: 49.9%ID: 37.3%WY: 43.2%MI: 46.7%1 Gila River, NMIA: 41.2%2 Hudson River, NYNE: 43.2%3 Upper Mississippi River, IL, IA, MO4 Green-Duwamish River, WANV: 43.3%UT: 34.8%NY: 47.9%CO: 34.6%5 Willamette River, ORKS: 40.7%6 Chilkat River, AKIN:IL: 33.0% 40.5%WV:40.6%MO: 38.4%KY: 41.8%7 South Fork Salmon River, IDAZ: 39.6%8 Buffalo National River, AROK: 42.2AR: 35.0%9 Big Darby Creek, OHNM: 35.4%10 Stikine River, AKLorCA: 57.2%TX: 43.9%LA:35.9% AK: 40.0%HI: 44.3%PA: 40.1%OH: 35.7%VA:36.7%AL:43.1%Less than 40%40%–50%50%–60%60%–70

Making WIC Work Better n Food Research & Action Center n May 2019 n www.FRAC.org 5 Part 1: The WIC Program: Basics and Benefits for Participants and Communities 6 Part 2: WIC Participants, Program Trends, Coverage, and Barriers 11 Part 3: WIC Recommendations and Strategies 16 Section 1: WIC Outreach and Promotion 17 Section 2: WIC Partnerships: Communication, Coordination, and Referrals 22