Transcription

Sharing and Accessing Administrative Data:Promising Practices and Lessons Learnedfrom the Child Maltreatment IncidenceData Linkages ProjectBeth Varley and Claire Smither WulsinIntroductionAccurate and ongoing surveillance of theincidence of child maltreatment and related riskand protective factors can help inform policyand programs, as well as shape prevention andintervention efforts. One approach to capturingthis information is by linking local, state, or federaladministrative records, such as those from childwelfare, health, social services, education, publicsafety, and other agencies.The Child Maltreatment Data Linkages (CMI DataLinkages) project identified five research groups(sites) with experience using linked administrativedata to examine child maltreatment incidence andrelated risk and protective factors. The projectsupported these sites to enhance their approachesto administrative data linkage through acquiring ofnew data sources, using new methods, or replicatingexisting methods. This brief highlights promisingpractices for sharing and accessing data basedon the five sites’ experiences. We discuss lessonslearned related to four key activities essentialto sharing and accessing data: (1) developingagreements for data sharing and use; (2) protectingthe data’s security, confidentiality, and privacy;(3) securing institutional review board (IRB)and other approvals; and (4) accessing the data.Additional detail can be found in the full report,Linking Administrative Data to Improve Understandingof Child Maltreatment Incidence and Related Risk andProtective Factors: A Feasibility Study.APRIL 2022 mathematica.orgPromising practices: sharing andaccessing data Researchers can build trust with data partners bymaking sure they know the federal, state, and local lawsand agency-specific regulations regarding data accessand by collaborating with liaisons in public agencies. Organizations interested in enhancing data linkagesmight be able to modify or amend existing data useagreements (DUAs) or research permissions to conducttheir work. An IRB that allows organization to use thedata for numerous projects and analyses of linked administrative data might also support these types of projects. Having a principal investigator (PI) with experience andknowledge of the IRB process may simplify the approval process. Project teams can use this experience tosubmit thorough materials, resulting in fewer revisionsto the submitted IRB package. Although DUAs often require stringent data securityprotocols, research centers working with administrativedata might already have such protocols in place. Collaborations with external entities to conduct data linkagesare an additional means to ensure the privacy and confidentiality of personally identifiable (PII) information. Using publicly available data or data that a variety of usersfrequently use (where there are established procedures inplace to access the data) can simplify data sharing. Plans and timelines for projects involving administrative data linkages should build in room for delays,especially related to data acquisition, and identifyopportunities to accelerate other activities or usethe time to prepare for analyses.1

Sharing data and accessing dataTable 1. CMI Data Linkages ProjectsReplicating the Alaska Longitudinal Child Abuse and Neglect Linkage (ALCANLink) methodologyAlaska Department of Health and Social Services and Oregon Health Sciences University(ADHSS/OHSU)The ALCANLink approach used a population-based, mixed-design strategy to integrate two sets ofdata: (1) those births that were sampled and mothers who subsequently responded to the PregnancyRisk Assessment Monitoring System survey and (2) child welfare and other administrative data. Alaskapartnered with Oregon to replicate this methodology and to estimate and compare the cumulativeincidence to first report, screen-in, substantiation, and removals by age 9.Methods to estimate the community incidence of child maltreatmentChildren’s Data Network and the California Child Welfare Indicators Project (CDN/CCWIP)This site focused on developing a methodology that used administrative data to estimate the number ofchildren who were victims of abuse or neglect. The site produced upper and lower bounds of estimatesthat reflected the number of children who the child welfare system identified as victims of abuse orneglect, as well as those who were victims but not identified as such by the system. The site tested themethodology using data from California and explored the potential for using it in other states.Using hospital data to predict child maltreatment riskChildren’s Data Network and Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego (CDN/Rady)This site tested the predictive value of integrating hospital data with vital birth records, statewide childprotection records, and vital death records to identify children who might be at an elevated risk of maltreatment. The site focused on validating a statewide predictive risk model by determining the extentto which children identified to be at high risk of maltreatment are also at elevated risk of injury, poorhealth outcomes, and mortality in childhood. The site used machine-learning methods to train probabilistic algorithms for linking hospital-system data to other administrative data sources. These data linkages aimed to better characterize the demographics and public service trajectories of Rady Children’sHospital patients.Understanding the effect of the opioid epidemic on child maltreatmentCenter for Social Sector Analytics and Technology (CSSAT)This site contributed to the knowledge about the opioid epidemic’s potential effects on child maltreatment. Drawing from several data sources across Washington State, this project examined theassociations among multiple indicators of child maltreatment, child welfare system involvement, andindividual- and community-level risk factors.Examining child maltreatment reports using linked county-level dataUniversity of Alabama School of Social Work (UA-SSW)This site examined how risk and protective factors relate to child maltreatment reports at the countylevel across the nation. The site linked county and state data from the National Child Abuse and NeglectData System to county and state data from the U.S. Census, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, and other sources. The site aimedto explain widely varying state- and county-level maltreatment rates and to develop valid ways to usecounty-level child maltreatment risk.APRIL 2022 mathematica.org2

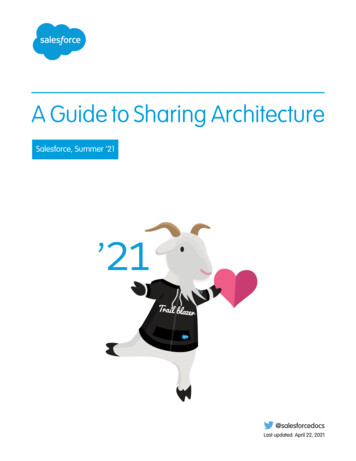

Sharing data and accessing dataDeveloping agreements for datasharing and useSites relied on existing and newagreements with data partners to accessdata necessary to complete CMI DataLinkages studies.1 Sites aiming to access new data(CDN/Rady, ADHSS/OHSU, and CSSAT) needed toidentify who had the authority to grant access.These sites also had to determine the appropriateprocesses for making requests. Understanding thestructure of state agencies was important forcompleting data sharing agreements andidentifying whether multiple approvals wererequired. Some projects (ADHSS/OHSU and CSSAT)worked with more than one state agency and had toidentify the approval authority within each. In onesite (ADHSS/OHSU), the core team included anadvocate in one state agency (Oregon HealthAuthority). This person was an effective liaison withher own agency and other state agencies thatprovided data or supported the analysis. In anothersite (CDN/Rady), the research team had to identifythe people with approval authority to share hospitaladmissions data: a chief administrative officer at thehospital and a transactions officer at the universitymedical school the hospital is affiliated with.All sites had DUAs between the principalinvestigator (PI) or research organization and eachseparate agency. No sites were required to havemultiparty DUAs. Multiparty DUAs can be morecumbersome to establish because they requirecoordination from multiple agencies.Provisions in sites’ agreements with datapartners focused on administrative,technical, and physical safeguards toprotect data. For example, agreements includedrequirements that data be transmitted and storedsecurely; that they not be moved, copied, ortransmitted without safeguards; that they not besold; that confidentiality was protected, and noidentifying information revealed in any researchdata sets or publications; that access to data belimited to only those directly involved, and that databreaches be reported as soon as possible. Theagreements also specified that facts cited about theAPRIL 2022 mathematica.orgdata must be accurate, and that the data could onlybe used for specified study purposes. Researchersbuilt trust with data partners by demonstratingfamiliarity with laws and regulations about dataaccess, as well as procedures for protecting data.Across sites, DUAs contained similarprovisions about the use of data,dissemination of results, and proceduresfor responding to disclosures of information. Thespecific details of each DUA varied by agency. Forexample, several sites’ agreements with the statechild welfare agency (ADHSS/OHSU, CDN/Rady, andCDN/CCWIP) specified that research must supportthe missions of public health and child welfareagencies, and that the agency must be consultedabout analysis results and dissemination productsbefore any dissemination takes place. The ADHSS/OHSU agreements also specified a “minimumnecessary information” policy: researchers mustrequest only the data necessary to answer theirresearch questions. Yet another agreement specifiedthat research staff consult with the data partner(CDN/Rady) about any disclosures that might berequired by law, so the data partner could considerhow to respond.The level of flexibility for sites to useacquired data for additional or alternativeanalysis varied by site, as specified intheir DUAs. For example, CDN/CCWIP, CDN/Rady,and CSSAT have broad DUAs with their childwelfare agencies, allowing them to use the data fornumerous projects and analyses. This broad licensewas an asset for their CMI Data Linkages projectsbecause they did not have to reestablish access orpermission to use the data through a new DUA.These broad DUAs still have agency reviewrequirements for use of the data even though thesites did not have to reestablish the access orpermission. For example, in the CDN/CCWIP andCDN/Rady sites, the DUA between CDN and theCalifornia Department of Social Services (CDSS)allows CDSS data to be used for “research purposesspecifically sanctioned in writing by CDSS.” Incontrast, the ADHSS/OHSU site had permission touse child welfare data for the CMI Data Linkagesproject specifically, rather than broad authorization.3

Sharing data and accessing dataTypes of provisions commonly included in DUAsData be transmittedand stored securelySafeguards necessary to move,copy, or transmit dataRestrictions onselling dataConfidentiality is protectedand no PII revealed in anydata sets or publicationsAccess would be limited toonly those directly involvedData breaches would bereported as soon as possibleUsing publicly accessible data simplifiedand accelerated data acquisition for somesites. No data-sharing agreement wasrequired for data sets in one site (UA-SSW), but anapplication process was required to obtain the datafrom the National Data Archive on Child Abuse andNeglect (NDACAN). Because NDACAN data arede-identified data submitted by states, the dataUA-SSW received were already clean. Other sites(ADHSS/OHSU and CSSAT) used someadministrative data sources, such as vital records,that a variety of users frequently access. In thesesites, states had established procedures for sharingthese types of records, which involved a request andstandardized transaction rather than a fullpartnership and approval process. These datasources offer advantages in terms of ease of access,but they also present limitations. Policies on thesedata sources are subject to change. Though theprocess is standardized, it can still be hard to accessthese data sources in most states, especially in away that allows individual-level linking.APRIL 2022 mathematica.orgProtecting the security,confidentiality, and privacyof dataTo access and use data, sites had to meet securitystandards established by multiple agencies andinstitutions, but sites’ existing protocols werestringent enough that they did not require adjustments. Sites had standard security protocols inplace, which they were able to use to meet CMI DataLinkages project requirements.Sites’ protocols abided by the separationprinciple— they separated personallyidentifiable information (PII) from analyticfiles and used it only to link records. In two sites(CSSAT and ADHSS/OHSU), research staff did nothave any access to PII. An external third partycompleted the linkages and returned a completedresearch file via encrypted transfer, with no identifying information. This increased data securitybecause no team members had direct access to theindividual-level records. In two other sites (CDN/CCWIP and CDN/Rady), a select group of nonresearch staff processed PII only on non-networked4

Sharing data and accessing datacomputing stations and used it only to link records.These data were not backed up externally, only tospecific encrypted devices. After linkages werecompleted, restricted analytic data sets werestripped of all direct identifiers and created andprocessed on a secure data server.In the site using only publicly accessible data fromNDACAN (UA-SSW), the research team members stillabided by standard security protocols. For example,they used double-password–protected computersin locked offices with encrypted cloud storage. Inaddition, to prevent the potential for identificationof individuals, NDACAN policy does not permit thesharing of county-level data for counties with fewerthan 1,000 child maltreatment reports.Securing IRB and other approvalsSome sites secured rapid IRB approvals ormodifications, whereas other sites experienced prolonged delays. Three sites thataimed to add new data sources to existing datalinkages (UA-SSW, CSSAT, and CDN/Rady) submittedIRB amendments or modifications to existing IRBpackages. Two sites (UA-SSW and CDN/Rady) completed IRB modifications that were approved relativelyquickly. University IRBs approved the modifications.The UA-SSW analysis did not involve individualidentifiable data and thus had an easier IRB process.One site seeking approval of an amendment througha state IRB (CSSAT) faced substantial delays. Becausean initial amendment request did not include all thevariables the team needed to access, they needed tosubmit another amendment. The team waited threemonths for approval of this amendment. An IRBamendment was also required because of a changein personnel for the project—specifically, the personwho was linking the records. Finally, additional stateand university approvals were required because thehome institution of the co-PI changed. In all, IRBprocessing in this site lasted about six months.The ADHSS/OHSU site required a new IRB for theproject. Team members noted that the process forsecuring a new IRB approval (from a university) wasrelatively smooth. For example, the board grantedAPRIL 2022 mathematica.orgapproval within the expected time frame and didnot request substantial new information about theplanned approach. Team members attributed thepositive experience with this approval process to anadvisor’s previous experience with the process.Accessing dataSites were generally successful in accessing the dataneeded for their CMI Data Linkages projects. Sitesaccessed and used 18 of the 20 planned data sourcesin their analyses.Sites’ experiences accessing data varied bythe type of data. Although some sites hadDUAs in place for child welfare data beforetheir projects began, establishing agreements toshare and use these data generally required substantial time and effort. Teams also navigated challengingprocesses to access hospital data (CDN/Rady andCSSAT), which required negotiation with multipleparties or relatively complicated approvals. The CDN/Rady team shared its impression that the process foracquiring hospital data was more cumbersome thanfor other types of data because private hospital datahas not been used for research as much as othertypes of data, such as vital records. Teams using vitalrecords data generally found these records relativelyeasy to access because state agencies had establishedprocedures in place to share them.For the two data sources that sites were not ableto access, the types of data differed, and so did thereasons that sites were not able to acquire them.A site seeking statewide data from a prescriptionmanagement system (CSSAT) was unable to accessthese data because of problems engaging the datapartner, the state’s department of health. The sitedid not have an existing relationship with this datapartner and found that communicating with keycontacts was difficult to sustain in the context ofthe COVID-19 pandemic. A site using National ChildAbuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) data(UA-SSW) was unable to access data for countieswith fewer than 1,000 child maltreatment records.The Administration for Children and Familiesestablished this threshold to lower the risk thatpeople living in smaller counties could be identified.5

Sharing data and accessing dataConclusionThe experiences and findings of the CMI DataLinkages sites offer important lessons about theprocess of using administrative data linkages tostudy the incidence of child maltreatment andrelated risk and protective factors. These lessonsunderscore the potential for these approaches toinform understanding of child maltreatment.Sites benefited from existing infrastructure andrelationships, which took time and effort to establish and maintain. To accomplish their projects,the sites drew on existing relationships with dataproviders, existing technical expertise, and existinginfrastructure. The sites nurtured relationships withdata stewards through regular meetings and consideration of the child welfare agency’s priorities whenconducting research—for example, considering andcommunicating how the research could help the dataproviders as well as the site. PIs and co-PIs were seasoned researchers with expertise in administrativedata linkage and analysis. Nearly all sites that neededagreements to access child welfare administrativedata already had them in place. However, the sites’data linkage projects required substantial effort andresources, particularly if researchers did not haveexisting infrastructure and experience.Although sites’ existing relationships, expertise,and infrastructure proved helpful in manycircumstances, existing relationships with datastewards did not guarantee smooth processes forsharing additional or new data.The sites needed to adapt to changes in circumstances and address unforeseen challenges thataffected their project plans. All sites had to adaptto changes in working conditions, priorities, andpartner availability resulting from the COVID-19pandemic.Overall, the CMI Data Linkages sites implementedpromising practices for sharing and accessingdata that enabled them to address high-priorityquestions about child maltreatment incidence andrelated risk and protective factors.EndnotesFor additional information about data use agreementsand research approvals by site, see Tables III.1 and III.2 inthe full report.1April 2022OPRE Brief: 2022-107Project officers: Jenessa Malin and Christine FortunatoProject Director: Matt StagnerDisclaimer: The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Officeof Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department ofHealth and Human Services. This report and other reports sponsored by the Office of Planning, Research, andEvaluation are available at www.acf.hhs.gov/opre.Connect with OPREAPRIL 2022 mathematica.orgFOLLOW US Mathematica, Progress Together, and the “circle M” logo are registered trademarks of Mathematica Inc.

child welfare agency (ADHSS/OHSU, CDN/Rady, and CDN/CCWIP) specified that research must support the missions of public health and child welfare agencies, and that the agency must be consulted about analysis results and dissemination products before any dissemination takes place. The ADHSS/ OHSU agreements also specified a "minimum