Transcription

My body, myselfAltered body image, intimacy and sex after breast cancerA policy report by Breast Cancer Care

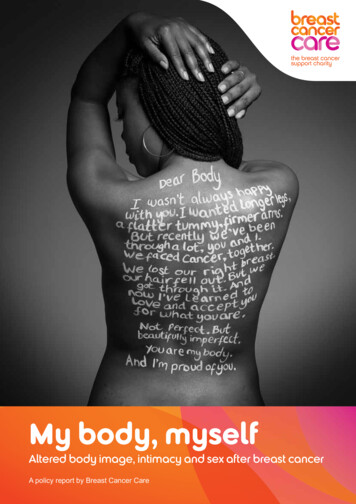

ForewordDiana Jupp,Director of Services,Breast Cancer CarePeople who use ourinformation and supportservices often tell usthat their breast cancerdiagnosis and treatmentshave affected their selfconfidence and the waythey view their bodies.We also hear how a negative self-image can inturn have a devastating impact on their social andintimate relationships.I am proud that Breast Cancer Care is here tosupport people through information, support andbringing people together so that they can worktowards building confidence after breast cancer.I am also proud that we are highlighting the oftenunspoken issue of altered body image after breastcancer, through this policy report and through ourbody image awareness campaign.One way that we are raising awareness is viaa short film and a series of adverts featuringJill, Heather and Ismena, who talk about theirexperience of body image after breast cancer.These adverts aim to raise awareness of theissues and the free information and support weprovide: www.breastcancercare.org.uk/body‘ I feel that my self-image andconfidence has been the hardestpart of cancer to overcome and thatmyself and other patients wouldbenefit from and appreciate improvedsupport in this area.’Lisa, 30We know there is no simple ‘one size fits all’solution and different people have differentneeds at different times. But there are thingsthat can help, such as talking to others in asimilar situation, information and support abouttreatment side effects such as menopausalsymptoms, and being referred to psychological orsex therapy services.Our goal is that everyone should have accessto the information and support they need, whenthey need it, to help them cope with altered bodyimage and its legacy after breast cancer.Through our information and support servicesand through the recommendations we are makingin this policy report, we are making progresstowards this goal.The needs of people directly affected by breastcancer are at the heart of this report andeverything we do. Here you will read direct quotesfrom our Breast Cancer Voices (people affectedby breast cancer who share their experience andexpertise to inform our work). What they have incommon is a powerful call to action: body imagematters after breast cancer, and addressingbody image and intimacy concerns should be asimportant as effective clinical treatment.3

AcknowledgementsThank you to the people affected by breast cancerwho shared their experiences with us to createthis report. Thank you also to the Breast CancerVoices who make up our Body Image ReferencePanel that has helped informthis report.Thank you to our Body Image Advisory Group*for guiding the focus of this report and reviewingdrafts of our recommendations.Thank you to the following people andorganisations for their comments on drafts of therecommendations:Relate; Relationships Scotland; Black HealthInitiative; Melissa Pilkington, Geeta Pateland Helena Lewis-Smith from the Centre forAppearance Research, University of the West ofEngland, Bristol; Dr Frank Chinegwundoh;Joanne Rule.Thank you to Melanie Larder, Dr Elizabeth Reedand Elizabeth Somerville, whose previous work atBreast Cancer Care also informed this report.Our body image adverts*Body Image Advisory Group membership:Ten Breast Cancer Voices (all women directlyaffected by breast cancer)Robbie Benardout, Camden Active Health TeamDr Ayse Gurpinar-Morgan, Clinical PsychologistMr Jian Farhadi, Consultant Plastic Surgeon andClinical Lead in Plastic Surgery, Guy’s and StThomas’ NHS Foundation TrustProf Diana Harcourt, Co-Director, Centre forAppearance Research, University of the West ofEngland, BristolAgnes McGowan, Lymphoedema TherapistRosie Small, Oncology NurseNicola West, Consultant Breast Care Nurse/Lecturer, Cardiff UniversityMelanie Yates, Counsellor.Breast Cancer Care staff:Charlotte Akeroyd, Marketing Manager/ClareKemsley, Marketing Manager (maternity cover)Liz Carroll, Assistant Director of Services –Co-chairSuzi Copland, Head of Services, SouthSophie Howells, Press and PR ManagerLizzie Magnusson, Policy and CampaignsManager – Co-chairEmma Lavelle, Campaigns and InvolvementCo-ordinatorRachel Rawson, Senior Clinical Nurse SpecialistDr Elizabeth Reed, Research Manager.We are grateful to Burdett Trust for Nursing forfunding this report.www.breastcancercare.org.uk/bodyWe’ve produced a short film and three adverts featuring women talkingabout their experiences of body image after breast cancer and showingtheir mastectomy scars. Appearing across the UK, they aim to raiseawareness of the issues and the free support we provide.We’ve also been asking people affected by breast cancer to write a letterto their body to share on our website their feelings about their body andwhat has helped them cope with these feelings.There are many ways to face breast cancer.We’re here to help people find theirs.Watch and share our video to support the 500,000women living with and beyond breast cancer.breastcancercare.org.uk/bodyFree helpline 0808 800 6000Registered charity in England and Wales 1017658 and in Scotland SC038104A letter to my bodyDear body,When I was first diagnosed it didn’t really sink in. I was on my own for that appointment and my nursekept asking if I was OK, expecting me to burst into tears. She even suggested I ring my husband, butthere was no signal in the hospital.Over the next few weeks I put you through all the tests they do. I had the surgery and then theradiotherapy. All the time, I didn’t even think about cancer.The radiotherapy made the scar on the nipple invert, causing a hole which I could only dry and washwith a cotton bud, and you bled a bit. My surgeon told me he would close the hole but it would meanlosing my nipple.I was OK with this (or so I thought) joking with him and my nurse that at 62 I didn’t think I was goingto be breastfeeding again. What I didn’t realise was I wasn’t likely to be having sex again either. Myhusband had not wanted sex since my diagnosis. Before I went for the first operation he said it didn’tbother him what I looked like afterwards. It didn’t matter to him if I had a mastectomy or not, he said.Breast cancer treatments also stopped my hair from holding hair dye, so I am now grey.The tamoxifen I was put on caused you – my body – to put on weight, but that was better than the sideeffects of the first two drugs my oncologist put me on. You’ve finally started to lose the weight, onestone so far and another one to go.This report was prepared by Policy andCampaigns Manager Lizzie Magnusson andCampaigns and Involvement Co-ordinator EmmaLavelle, Breast Cancer Care 2014email campaigns@breastcancercare.org.ukMy breast nurse has been very understanding. I realise there are women a lot worse off than me and Ihate bothering her with trivial things. Needless to say, she told me off for thinking like that.She referred me to a psychologist and suggested a referral to a plastic surgeon, as the loss of thenipple has really affected me. I find I cannot look at you in the mirror and my husband stays ‘asleep’while I get dressed and comes to bed after me. I have also burst into tears at my last appointments atthe clinic and at the prosthesis fittings.I bought stick-on nipples, a leaflet I picked up at the clinic. Having these means I can wear some ofmy unpadded post-surgery bras – one goes on the prosthesis. It doesn’t solve the no sex problem,though, and it has been over two years now. He even finds it hard to hug me, and I do miss it all. If Italk to him about it he just rolls his eyes, almost saying I’m talking rubbish. He doesn’t see the tears ashe never comes into the appointments with me.Jane45

Introduction‘ Expressing sexuality remains important tomany people with cancer, regardless of age,and can be fundamentally compromisedby the condition and its treatment. Cancerhas an impact on intimate relationships,can cause specific sexual dysfunction, andaffects how people perceive their sexualidentity through, for example, a changedbody image. Because sexuality is an issuethat many people – health and social careprofessionals and patients – find difficult toaddress, there can be a failure to offer orseek information and support.’Improving Supportive and Palliative Carefor Adults with Cancer (NICE, 2004)‘ Body changes can occur quickly or overa long period of time. They can affect theway you think and feel about your body(body image), which can affect your selfconfidence. You might also worry thatpeople will treat you differently because ofa change to your body. Concerns aboutyour body can occur at any time. Somepeople will focus on just getting throughtheir treatment and won’t think about itsimpact until much later.‘ Changes to your body may seem moreimportant after you leave hospital, at thestart of another type of treatment or afterfinishing treatment. Some people may feelthat they “don’t recognise themselves” orthat they “lose themselves”.’NHSInform (Scotland) – Cancer Zone,Coping with body changesA breast cancer diagnosis and breast cancertreatments can bring changes related to aperson’s body image and sexuality, which inturn can have a devastating impact on intimaterelationships.A report published by the All Party ParliamentaryGroup on Body Image (APPGBI) in 2012emphasises the devastating impact a negativebody image can have on someone. The reportstates that in the UK ‘body image dissatisfactionis high and on the increase and is associatedwith a number of damaging consequences forhealth and wellbeing’ (APPGBI, 2012).Defining the term ‘body image’ can be difficultbecause it means different things for differentpeople, but as an organisation, Breast CancerCare holds with the definition coined by SarahGrogan. It provides a simple but inclusivedescription of the term that is easy toidentify with: ‘.a person’s perceptions,thoughts and feelings about his or her body’(Grogan, 2008).About a half a million people are alive todayfollowing a diagnosis of breast cancer(Maddams et al, 2009). Breast Cancer Care isable to provide information and support relatedto altered body image, intimacy and sex afterbreast cancer – an area of long-term cancercare we know is underrepresented. We arecampaigning for support and information aboutaltered body image, intimacy and sex to beavailable to everyone affected by breast canceras an essential and integral part of their cancertreatment and care.Impact on intimate relationshipsThis report offers an overview of the key issuesinvolved in altered body image after breastcancer, with a particular focus on changes insexual and self-identity, and the impact thesechanges can have on intimate relationships, bothexisting and new.We make recommendations on how NHS servicesin England, Scotland and Wales can best supportpeople affected by breast cancer in relation toaltered body image, intimacy and sex.Until recently the cancer policy agenda had beendominated by a focus on clinical outcomes andimproving cancer survival. Recently, however,there has been a shift in the focus towards a moreholistic and longer-term approach, looking at thecare provided for people living with or beyondcancer. This approach recognises that cancercare needs to be more than providing effectiveclinical treatment. It should also focus on otheraspects of a person’s life and wellbeing, includingself-image, social interactions and intimaterelationships, sometimes well after treatmenthas ended.We are campaigning for altered body image andintimacy concerns to be consistently recognisedas part of this holistic, person-centred approachto cancer policy and cancer care.Evidence base for this report Literature review (mainly 2006 until thepresent day) on altered body image,intimacy and sex after breast cancer. Analysis of focus groups held between2009 and 2011 with people affected bybreast cancer. Feedback from women affected by breastcancer, healthcare professionals andother experts on our Body Image AdvisoryGroup* (see p4). Feedback from our Body ImageReference Panel of 14 women affected bybreast cancer. Previous Breast Cancer Care reports onchallenging inequalities in cancer care,particularly the inequalities that exist forpeople from black and minority ethnicbackgrounds, older people, and lesbianand bisexual women. Personal stories from people affected bybreast cancer gathered in 2013.We examine altered body image, intimacyand sex after breast cancer under the followingfive headings. My body, myself – six statements forbreast cancer services, see p8. The impact of altered body image, see p9. Access to information and support, see p16. Recommendations for serviceimprovements, see p20. National standards, public policyand guidance, see p28.67

My body, myself –six statements for breast cancer servicesThese statements summarise the information and support that people who use our services haveidentified as necessary to address concerns about altered body image, intimacy and sex.We’ve developed them with people directly affected by breast cancer, healthcare professionals and otherexperts through our Breast Cancer Voices, Body Image Advisory Group and Body Image ReferencePanel. We address each statement in Recommendations for service improvements (see p20).1. I want to be treated as a whole person. I wantissues relating to changes to my body, andconcerns about intimacy and sex to be takenseriously, assessed and addressed as anessential and integral part of my treatment andongoing care for primary or secondary breastcancer.2. I want to be listened to as an individual. I donot want assumptions to be made about how Ifeel about my body, intimacy and sex based onmy relationship status, age, gender, religiousbackground, ethnicity, disability or sexualorientation.3. I want to be able to access specialistinformation about altered body image,intimacy and sex throughout my breast cancertreatments and after treatment has ended. Iwant this information to include practical ideas.I may want this information in a language otherthan English.84. I want to know about and be referred toservices in the NHS and voluntary sector thatoffer support with altered body image, intimacyand sex. These services should be available tome regardless of where I live.The impact of alteredbody image‘ There is currently a variation in the provisionand quality of psychological approaches andservices offered to patients with cancer. Forexample, women with breast cancer mayneed support due to traditional symbolsof feminine sexuality being challenged bytreatments: loss of a breast(s), changes tobreasts, loss of hair and, for some youngerwomen, fertility issues.’Living with and beyond cancer: takingaction to improve outcomes (NationalCancer Survivorship Initiative, 2013)5. I may want to be able to get in touch with otherBreast cancer treatments affect those parts ofthe body and bodily functions that are particularlyassociated with femininity and female desirability(such as breasts, fertility and hair).6. I may want my partner to be involved in theFor men diagnosed with breast cancer, it canbe distressing to be diagnosed with a conditioncommonly seen as a ‘feminine disease’ (Donovanand Flynn, 2007). As such, treatments can have aparticularly negative (and sometimes long-term)impact on a person’s self-image, sexual identityand intimate relationships (Arroyo et al, 2011;Fallbjörk et al, 2012).people affected by breast cancer to talk aboutchanges to my body and to share copingstrategies.support I receive about body image, intimacyand sex or to receive information specificallydesigned for partners.There is a wide spectrum of altered body imageexperiences and feelings after breast cancer,with everyone’s experience personal to them.For example, one study describes the differentpersonal meanings of having a mastectomy asranging from ‘No big deal’ to ‘Losing oneself’(Fallbjörk et al, 2012). The possible changes inbody image after breast cancer can be looselygrouped as affecting a person physically,psychologically and socially. These headingsare broad and their content often overlaps. Someexamples of the impact of altered body imageafter breast cancer under these headings follow.‘ more needs to be done to promotehelp for women and for these issuesto be taken seriously. After all, thereis enough to cope with emotionallywith a cancer diagnosis without alsofeeling that there is nobody to talk toabout body image issues, and that itis somehow selfish or vain to worryabout them.’Rachel, 47Breast cancer treatments can also have an impacton sexual functioning in women and men, withside effects such as low sexual desire and vaginaldryness in women. It may lead to temporary orpermanent infertility (Panjari et al, 2011; BreastCancer Care, 2011 and 2013). Sexual dysfunctionand changes to fertility can have devastatingconsequences for a person’s self-esteem andself-image and for their intimate relationships,existing and new.9

Physical impactWhat people tell usThis refers to changes in bodily appearance andrelated practical issues. Examples of the physicalimpact of breast cancer treatments include the listbelow. Loss of breast(s) or breast tissue throughsurgery for breast cancer or breast cancerrisk-reducing surgery. This could be breastconserving surgery, otherwise referred to aslumpectomy or wide local excision – in whichthe cancer is removed along with a marginof normal breast tissue – or mastectomy, inwhich all the breast tissue including the nipplearea is removed. Asymmetry in appearance, for example afterthe removal of breast tissue on one side, orasymmetry after breast reconstruction. Difficulties and lack of choice in finding andbuying suitable and attractive bras andswimwear and lack of access to specialistpost-surgery bra fitting. Difficulties and lackof choice in finding and buying attractiveclothing, particularly summer or evening wearwith low-cut tops. Difficulties in finding comfortable and wellfitting breast prostheses. Some women havealso reported difficulties in obtaining breastprostheses in a colour suitable for black andAsian skin. Scarring from surgery – for both tumourremoval and breast reconstruction – and fromradiotherapy.‘ ‘ Total or partial body hair loss caused bychemotherapy and hair regrowth issues. Haircan grow back different from the hair beforetreatment, either permanently or temporarily.I had a lumpectomy three years agoand have noticed that my breast onthat side is smaller and the nipplesticks out more. The breast is alsoabout 2cm higher than the nontreated breast.’ Skin changes after some treatments, such asskin discolouration or dry skin. This may be aparticular issue for black and Asian people. Menopausal symptoms as a side effect ofbreast cancer treatment. Including hot flushesand vaginal dryness. Some chemotherapy and hormone therapiesused in the treatment of breast cancer canbring about an early menopause and cancause temporary or permanent infertility.Chemotherapy can affect sperm production,leading to temporary or permanent infertility inmen. Weight gain as a side effect of breast cancertreatment. Lymphoedema, when the arm, hand orbreast area swells because of damage tothe lymphatic system caused by surgery andradiotherapy. Secondary breast cancer (where the cancerhas spread to another part of the body) canresult in many different physical symptomsincluding pain. Symptoms depend on wherethe cancer has spread to in the body.The menopause was brought onquickly because of the chemotherapyand drug programme bearing in mindmy age (36). At times I would havehot flushes every 15 minutes anddifficulty at night with joint aches andgetting hot.’Lorna, 45Susan, 69‘ ‘ or me the biggest change wasFbeing flat chested on my right sidefollowing my mastectomy. Thishas really taken some adjusting to.It is easier to cope with in winterthan summer. I have also foundI am gaining confidence with mychoice of clothes: prior to the breastcancer I liked low-cut tops; now Iam much more conservative but dotry and look nice as it makes mefeel so much better. I had a singlemastectomy so being “lopsided” hasalso taken some getting used to.’Jennifer, 41‘ lthough I had an immediateAreconstruction, I was never fullycomfortable with it and felt I neededto adjust my clothing to hide it. I wasalso concerned about the weight gainfrom tamoxifen, but managed to getthis under control once I stoppedtaking it.’Mairead, 58I feel OK about my body when I haveclothes on but feel self-consciousabout the changes when I don’thave clothes on. I was glad to getrid of the tumour. However, I didn’trealise that a lumpectomy wouldchange the shape of my breast as ithas done.’Susan, 69‘ y main concern was always to getMrid of the cancer. Unfortunately, thebreast went with it but I don’t thinklosing the breast affected me asmuch as accepting the new breast, ifthat makes sense. The old one couldgo, it was diseased and could havekilled me – the new is different; it’sheavy, it’s numb but often painful andit had no nipple for a long time.’Jasmin, 44‘I found the whole experienceof preparing for hair loss, and thebuild-up to it, to be a very distressingand traumatic time.’10Susan, 5311

Psychological impactWhat people tell usThis refers to changes in emotional wellbeing,including difficulties with anxiety and depression.Examples include the points below. Feelings of permanent and temporaryloss and associated depression, anxietyand feelings of grief. People often use theword ‘loss’ to describe a lack of somethingphysical and notional or spiritual after breastcancer. This includes loss of: breast/sand breast tissue, nipple/s, hair duringchemotherapy; skin sensation where surgeryhas taken place; fertility through cancertreatments; confidence; a sense of femininityor masculinity; a sense of self or clear identity;a sense of wholeness or bodily integrity; asense of attractiveness or sensuality. Feeling less confident or self-consciousbecause of self-awareness of changes inbody or appearance. Feelings of being incomplete or a fraud andconnected feelings of depression, anxiety andshame, such as feeling ‘less of a woman’ or‘less of a man’. Changes in sexual identity, includingfeeling less attractive or unattractive,experiencing changes to traditional symbolsof femininity and feminine desirability throughbreast cancer treatments, such as thebreast(s), hair and, for some younger women,fertility. For men diagnosed with breastcancer, living with the stigma of a ‘woman’sdisease’ can challenge sexual identity. Changes in self-identity and confusionabout identity, such as feelings of being ‘lessfeminine’ or ‘less masculine’. This can includefeeling as though the identity of ‘cancerpatient’ or ‘cancer survivor’ dominates otherfeelings about how you see yourself or areseen by others. Reminder of the cancer diagnosis. Alteredappearance can be a positive reminderof successful treatments. However, it canalso be a negative reminder of the cancerdiagnosis and associated fear of cancerrecurrence, or a reminder that a person isliving with secondary breast cancer (breastcancer that has spread to another part of thebody and can be controlled but not cured). Loss of trust in the body. Some women talkof their body having let them down after beingdiagnosed with breast cancer and feelingthat they have no confidence in their bodyanymore. This can be a particular issue forwomen with secondary breast cancer (wherethe cancer has spread to another part of thebody).‘I am still working out how I feel aboutthe changes my body has undergone.Do I feel maimed? Or am I newAmazon woman, one-breasted andbeautiful?! I don’t know.’ hen I lost my breast I lost myWsexuality. I don’t feel feminine orwhole and I feel angry and sad thatthis has happened.’I felt really low about myself. Peopleexpect you to be happy because youare not dying but I felt so challenged.I was only 36 and felt like I was livinga lie. I still feel a bit like this. I mightlook good on the outside but if I tookmy clothes off, I’d just have to bebrave.’Tamsin, 43‘Lorna, 45‘ I do miss my real breasts as they aresuch a big part of being a woman.’Natalie, 43Kate, 50‘ ‘ When I went to a lingerie shop therewas a beautiful set of cream lacelingerie. I felt ashamed to be lookingat it and I still feel a sick lump in thepit of my stomach that someone likeme could look at it.’Sarah, 44‘ ollowing my mastectomy I alsoFclearly remember waking up inrecovery and being so aware that mybreast had gone, it felt so empty.No-one had talked to or preparedme for this feeling. I cried for hourspost-op.’12‘ I am so pleased that the cancer hasbeen taken away but grieve for theloss of the breast I had.’Tracy, 49‘ Another big thing is the loss in trustof my body, especially after beingdiagnosed with secondaries last July.The treatment for this has turned intoa watch-and-wait but the diagnosisreally was such a shock and it willtake time to learn to trust my bodyand that every twinge is not a newrecurrence or cancer.’Vicky, 33Jennifer, 4013

Social impactWhat people tell usThis is about changes in how people respondto the social environment and changes in socialand intimate relationships. Examples include thepoints below. Changes in a person’s role within thefamily, with a partner and with friends.This can include the reactions of others tobodily changes caused by breast cancertreatments. It can involve feeling that theidentity of ‘cancer patient’ or ‘cancer survivor’dominates other feelings about how you seeyourself or are seen by others, or feeling asthough an intimate relationship has beenreplaced with the roles of ‘carer’ and ‘patient’. Changes in sexual functioning after breastcancer treatments, such as vaginal dryness,which can cause pain or discomfort duringsex, reduced libido, loss of orgasm andorgasm intensity, discomfort from scarring,the impact of fatigue (a common treatmentside effect) and lack of sensation in breasts. Challenges to existing intimaterelationships. This can be linked to feelingsof unattractiveness or the impact of thephysical side effects of treatment on sexualfunctioning. It might be linked to difficulties intalking as a couple about breast cancer, or apartner’s response to an altered body imageand its impact on the relationship.‘ ‘ Challenges in forming new relationships.For example, feeling anxious about revealinga breast cancer diagnosis to a new partneror unable to start a new intimate relationshipbecause of concerns over not feeling sexuallyattractive or sexual dysfunction. Being unable to return to paid employmentor having to take time off from employmentdue to body image issues, or feeling lessconfident in a job role. Finding it distressing to use communalchanging rooms in sports facilities andclothes shops. Social isolation or changes in socialinteractions due to lack of self-confidenceand concerns that appearance changes willreveal a breast cancer diagnosis to others.Self-confidence has plummeted! People say, “Wow haven’t you donewell, you look great’’ etc, but inside Ifeel that I look freaky, the way I dresshas changed . I just want to blendinto the background.’Elaine, 45‘ He [my partner] was much moreupset about it than me and initiallycould not look at my scar. He alsowanted me to have reconstruction,which I did not want.’Janet, 43‘ Prior to being with my new partner,I was very worried about meetingsomeone as I felt like a freak.’’‘ I do not like looking at myselfanymore and believe my husbanddoesn’t either as he waits for meto go to bed and to get up. We nolonger have any intimacy.I had a mastectomy at age 38. Icouldn’t bear to look at myselfhaving been mutilated, much lesshave anyone else look. Sexualrelationships were then off theagenda for good. I am now aged 71.’Anon, 71‘ I still really care about myappearance. I worry about mybreasts and how numb they are andhow the long menopause [broughton by breast cancer treatments] hasaffected my sexual feelings.’I think it is important to acknowledgethe impact that your changes in bodyimage have on children. I let both ofmy children look at my mastectomywound when they wanted to, andthey both took this in their stride. Itwas my hair loss during my chemothat they struggled with.’Lorna, 45‘ We have grown apart because of themastectomy. We have no sex life, Ihave no libido and now we have nomarriage. I can’t ever imagine beingintimate with anyone again.’Jane, 61‘ Irene, 57‘ Natalie, 43’14Once my breasts had healed, Ibelieve it was difficult for him [mypartner] to touch my breasts. Wetalked and gradually he was able totouch and kiss my breasts.Kate, 50‘ Our physical relationship hassuffered. the physical discomfortof the side effects and surgery,tiredness and feeling veryunattractive.’Karen, 52Jennifer, 4115

Access to informationand supportThere are several barriers for breast cancerservices to overcome in order to address alteredbody image, intimacy and sexual concernseffectively.Altered body image and changes in sexualityaffect different people in such different ways thata standard approach isn’t appropriate – a range ofinformation resources and service referral optionsis needed.Altered body image and concerns aboutintimacy and sex can remain silent issues incancer care, with patients and healthcareprofessionals sometimes reluctant to talk aboutthem. Also, altered body image and intimacyconcerns can arise long after treatment andhospital-based appointments have ended sothat the people affected may feel that they don’tknow where to turn to access the specialistsupport they need. These barriers are exploredfurther below.Assessment of individual needs‘ At no time has anyone from themedical profession asked if I neededany help or advice around any ofthese issues. It is as if they areonly concerned with the physicaltreatment of the cancer, and thatyou are almost being vain if youcare about any of the rest. Indeed,the firs

women living with and beyond breast cancer. breastcancercare.org.uk/body Free helpline 0808 800 6000 Registered charity in England and Wales 1017658 and in Scotland SC038104 Acknowledgements Thank you to the people affected by breast cancer who shared their experiences with us to create this report. Thank you also to the Breast Cancer