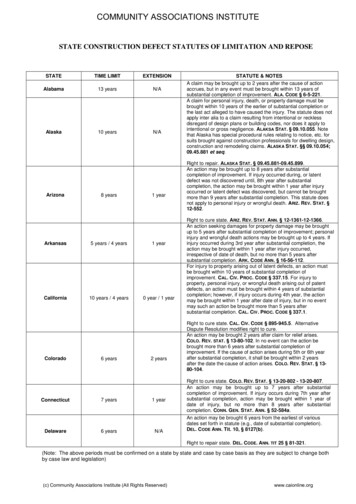

Transcription

FEATURE TITLECONSTRUCTION LAWConstructionDefect Statutesof Limitationand ReposeUpdatePart 1BY RON A L D M . S A N D GRU N DA N D JO SE PH F. “ T R I P ” N I ST IC O I I I26 C OL OR A D O L AW Y E R DE C E M BE R 2 0 2 0

This article examines significant changes in and clarifications to the law since 2005 interpretingand applying Colorado’s real property improvement statutes of limitation and repose.This Part 1 discusses the scope and application of these statutes, events that triggerthe repose and limitations periods, claims and activities not subject to these statutes,and challenges in applying these statutes to multifamily construction activities.This article examines significant changes inand clarifications to the law since 2005 thatinterpret and apply CRS § 13-80-104’s realproperty improvement statutes of limitation(RP-SOL) and repose (RP-SOR).1 This part 1 discusses towhom the RP-SOL and RP-SOR apply; the scope of theselaws; what events trigger the running of the repose andlimitations periods; claims and activities not subject tothese laws; and the challenges of applying these laws tomultifamily construction activities.2Real Property ImprovementStatute of LimitationsThe RP-SOL is located in CRS § 13-80-104, which providesin pertinent part:(1)(a) Notwithstanding any statutory provision to thecontrary, all actions against any architect, contractor,builder or builder vendor, engineer, or inspectorperforming or furnishing the design, planning, supervision, inspection, construction, or observationof construction of any improvement to real propertyshall be brought within the time provided in section13-80-102 after the claim for relief arises, and notthereafter . . . .(b)(I) Except as otherwise provided in subparagraph(II) of this paragraph (b), a claim for relief arises underthis section at the time the claimant or the claimant’spredecessor in interest discovers or in the exercise ofreasonable diligence should have discovered the physicalmanifestations of a defect in the improvement whichultimately causes the injury.(c) Such actions shall include any and all actions intort, contract, indemnity, or contribution, or otheractions for the recovery of damages for:(I) Any deficiency in the design, planning, supervision, inspection, construction, or observation ofconstruction of any improvement to real property; or(II) Injury to real or personal property caused byany such deficiency; or(III) Injury to or wrongful death of a person causedby any such deficiency. (Emphasis added.)Actions subject to CRS § 13-80-102 “must be commenced within two years after the cause of action accrues. . . .” The RP-SOL is an affirmative defense to be pled andproven by the party asserting it.3Real Property Improvement Statute of ReposeThe RP-SOR is also located in CRS § 13-80-104:(1)(a) Notwithstanding any statutory provision to thecontrary, all actions against any architect, contractor,builder or builder vendor, engineer, or inspector performing or furnishing the design, planning, supervision,inspection, construction, or observation of constructionof any improvement to real property shall be broughtwithin the time provided in section 13-80-102 after theclaim for relief arises, and not thereafter, but in no caseshall such an action be brought more than six yearsafter the substantial completion of the improvementto the real property, except as provided in subsection(2) of this section.(2) In case any such cause of action arises during thefifth or sixth year after substantial completion of theimprovement to real property, said action shall bebrought within two years after the date upon whichsaid cause of action arises.4The RP-SOR does not deprive a court of jurisdiction.Instead, defendants must plead and prove it as an affirmative defense, and they may waive the defense if nottimely raised.5Construction Professionals Subjectto the RP-SOL and RP-SORThe RP-SOL and RP-SOR apply broadly to most constructionprofessionals involved in real estate development andconstruction. They do not apply to a non-commercialDE C E M BE R 2 0 2 0 C OL OR A D O L AW Y E R 27

FEATURE TITLECONSTRUCTION LAWreal property improvement seller or commoninterest community declarant unless thatperson also “perform[s] or furnish[es] thedesign, planning, supervision, inspection,construction, or observation of construction ofany improvement to real property . . . .”6RP-SOL and RP-SOR ScopeThe RP-SOL and RP-SOR apply only toclaims arising from real property improvement construction where the improvementis essential and integral to the function ofthe construction project.7 A highly relevantfeature of an improvement to real property is“permanence”—whether the property ownerintends it to remain permanently even if itcan be removed.8 An “improvement” withinthe meaning of the RP SOL and RP-SOR canbe “a discrete component of a larger undertaking,” such as one building in a multi-buildingcondominium project.9 However, the RP-SOLand RP-SOR do not apply to claims against adeveloper or seller of unimproved lots.10Statutory Exception for Persons inActual Possession or ControlCRS § 13-80-104(3) creates an exception to theRP-SOL and RP-SOR where the party seekingto apply the RP-SOL or RP-SOR had actualpossession or control of the defective realproperty improvement when the injury ordamage occurred:The limitations provided by this section shallnot be asserted as a defense by any personin actual possession or control, as owner ortenant or in any other capacity, of such animprovement at the time any deficiencyin such an improvement constitutes theproximate cause of the injury or damagefor which it is proposed to bring an action.Although Colorado’s appellate courts havenot yet construed this provision, the North Carolina Supreme Court construed a substantiallysimilar statute11 and held that the language “byits terms, plainly excludes” from the reposestatute’s reach “any person who is in possessionor control of property at the time that person’snegligent conduct proximately causes injuryor damage to the claimant.”12 The Court heldthat the exception did not apply in that case28 C OL OR A D O L AW Y E R Practice Pointer: CRS § 13-80-104(3) and Insurance CoverageCRS § 13-80-104(3) creates an exception to the RP-SOL and RP-SOR where thedefendant asserting these defenses had actual possession or control of the defectiveproperty improvement when the injury or damage occurred. Note that many liabilityinsurance policies exclude liability coverage to insured defendants for damage toproperty the insured owns, rents, or occupies. This policy provision does not appear, byits terms, to apply to a developer who merely retains voting control over an HOA board.Also, the policy may not exclude coverage for damage occurring after the defendantsells the property. Variations in policy exclusion language will affect the coverageanalysis.“The RP-SOLand RP-SORapply only toclaims arisingfrom real propertyimprovementconstructionwhere theimprovementis essential andintegral to thefunction of theconstructionproject.”because the damage occurred after the plaintiffhad purchased the house.13A later North Carolina decision similarlyheld that the North Carolina repose statuteDE C E M BE R 2 0 2 0does not bar claims brought against a construction professional who the plaintiff allegedhad “possession or control” over the subjectcondominium buildings and “knew or shouldhave known of the existence of the defects uponwhich [the plaintiff’s] claim rests.”14 The NorthCarolina Court of Appeals found that the trialcourt erred by granting summary judgment infavor of the construction professional, givendisputed questions of fact regarding whetherthe statutory exception applied. For example, itnoted that the defendant “arguably” controlledthe condominium association through itsappointment of board members until turnover,and the defects allegedly manifested beforeturnover.15 The court therefore concluded that“the extent to which the ‘possession or control’exception to the statute of repose defenseapplies to [the defendant] is a question forthe jury.”16A number of Colorado district courts haveapplied CRS § 13-80-104(3). Several courtsapplied this subsection to declarant-developerswho controlled a common interest communityand its homeowners association (HOA) duringthe declarant control period, precluding ortolling application of the RP-SOL and RP-SORduring that time.17 One district court held thatthe statute applied to a developer-declarant whocontrolled an HOA before turning its controlover to its unit owners, but not to a generalcontractor who performed the constructionwork.18 Another district court held that § 104(3)applied to a developer, its principals, and theproject’s general contractor, but not to thedesigner or concrete subcontractor.19

Relationship between RP-SOL andOther Statutes of LimitationsThe RP-SOL is written quite broadly and isintended to cast a wide net. Yet Colorado courtshave, on occasion and under unique facts,found that the RP-SOL did not apply, and thata different, more specific, or later-enacted,statute of limitations controlled. For example, inHersh Companies v. Highline Village Associates,the Colorado Supreme Court held that thespecific breach of warranty statute of limitationsrather than the RP-SOL applied to a breachof a “warranty to repair” defects because theclaim is beyond the RP-SOL’s scope.20 The Courtalso noted, “[w]hen more than one statute oflimitations could apply to a particular action,the most specific statute controls over moregeneral, catch-all statutes of limitations.”21In Stiff v. BilDen Homes, Inc., the ColoradoCourt of Appeals applied CRS § 6-1-115, ratherthan CRS § 13-80-104, to homeowners’ ColoradoConsumer Protection Act22 deceptive tradepractices claims arising from alleged misrepresentations regarding various constructiondefects.23 And in Frisco Motel Partnership v.H.S.M. Corp., the Colorado Court of Appeals heldthat the specific limitations statute applicableto breaches of fiduciary duty, rather than theRP-SOL, governed a breach of fiduciary dutyclaim arising from defective construction.24Property owners often argue that CRS § 1380-101(1)(c)’s three-year statute of limitationsrather than CRS § 13-80-10’s two-year statuteof limitations applies to misrepresentationclaims (including for nondisclosure) arisingfrom construction defects. Several Coloradodistrict courts have embraced this view. 25This argument is based, in part, on the factthat a misrepresentation claim is founded ona defendant’s material misrepresentation oromission, not its participation in defectiveconstruction, and thus is arguably beyond thescope of the RP-SOL.26This distinction is underscored by thedifficulty of applying the triggering event forthe RP-SOL—that the homeowner knew orshould have known of the manifestation of aconstruction defect—to claims for misrepresentations or nondisclosures. A cause of actionfor these latter claims accrues when the “fraud,misrepresentation, concealment, or deceit isdiscovered or should have been discovered bythe exercise of reasonable diligence.”27 Thus, acause of action for negligent construction (e.g.,discovery of a defect’s manifestation) mightaccrue either before or after a cause of action“A commonproblem inapplying theRP-SOL andRP-SOR isdetermining whena homeowner‘discovered orshould havediscovered’ themanifestation ofthe defect at issue.This is often a factquestion forthe jury.”for misrepresentation accrues (e.g., knowledgethat a material fact was misrepresented duringthe sale).For example, a builder might commit fraudby concealing from a homeowner the presenceof adverse soil conditions beneath a home inviolation of its common law duty to discloselatent defects, or in violation of Colorado’ssoils disclosure statute, CRS § 6-6.5-101.28However, the mere presence of such adverse soilconditions alone probably would not give riseto a claim for defective construction29 until thedefectively constructed improvement’s interaction with the soils damages the improvement.30Triggering the Statute of Limitations:Defect ManifestationA common problem in applying the RP-SOLand RP-SOR is determining when a homeowner“discovered or should have discovered” themanifestation of the defect at issue. This isoften a fact question for the jury.31 The issue canbecome especially thorny when a reasonableperson would consider the observed condition“normal” and not the manifestation of a “defect,”or when multiple, similar defects manifest overtime but may not share the same cause.Defect versus Typical Condition withinConstruction TolerancesProperly poured interior concrete slabs andfoundation walls typically develop hairlinecracks and exhibit some spalling (surfacechipping) over time as the concrete fully cures.Such slabs may also evidence cracking ormovement due to normal settlement overthe underlying fill. Nevertheless, years afterthe home is sold, these cracks may materiallyexpand, and the concrete may begin to movedifferentially, due to pressures exerted bywater buildup in underlying or adjacent soils.This situation raises the question whether thelegislature intended to require homeownersto sue their homebuilder whenever minorconcrete cracks first appear simply to protectagainst the RP-SOL or RP-SOR expiring, even ifthe observed condition is still within reasonablynormal limits or construction tolerances.32In Stiff, the Colorado Court of Appeals heldthat minor cracks or movement should notbe deemed the “manifestations of a defect”sufficient to trigger the RP-SOL’s running if theyare within construction tolerances or a normalrange of movement.33 While Stiff mentions thatthe statute is triggered when the plaintiff knewor should have known of the damage and itscause, Stiff ’s analysis focused on the “damage”at issue—that is, when did the crack ceasebeing routine or expected and become whatDE C E M BE R 2 0 2 0 C OL OR A D O L AW Y E R 29

FEATURE TITLECONSTRUCTION LAWa reasonable person would recognize as thephysical manifestation of a defect? This “cause”language may be considered dicta.This view of Stiff is supported by United FireGroup ex rel. Metamorphosis Salon v. PowersElectric, Inc., where the Colorado Court ofAppeals held that an electrical fire was themanifestation of an electrical defect that triggered the RP-SOL, despite the fact that theclaimant was unaware that the fire was causedby an electrical defect until it received the fireinvestigator’s report weeks later.34 The Courtdistinguished Stiff, reasoning that its holding“focused on the amount of damage necessaryto trigger the two-year statute of limitations.There was no discussion of whether it was alsonecessary for the cause of that damage to beknown to begin the limitations period.”35 TheCourt thus viewed as dictum “Stiff ’s referenceto learning the cause of the damage as beingnecessary to activate the statute of limitations.”36The Colorado Supreme Court’s later opinionin Smith v. Executive Custom Homes, Inc. alsodoes not appear to affect Stiff ’s holding thata property condition is not the manifestationof a defect unless it reflects the existence of adefect, as opposed to a non-defective conditionwithin normal construction tolerances.37 Smithexpressly noted that the limitations periodbegan to run when the property owner noticedthe “obvious physical manifestations of whatappear[ed] to be a construction defect . . . .”38Thus, in combination, Stiff and Smith stronglyimply that to begin the limitations period, themanifested condition should alert a reasonableproperty owner that the condition is the outwardexpression of a construction defect, not simplyan expression of a range of typical or normalnon-defective conditions. If the limitationsperiod could be triggered under circumstanceswhere a reasonable person would not haverecognized the condition as manifesting a defect,constitutional concerns might arise, which willbe discussed more fully in part 2 of this article.Multiple, Similar DefectsOccurring Over TimeAnother common problem arises when multipledefects manifest at different times, especiallywhen the cause of the separate defects may30 C OL OR A D O L AW Y E R “The RP-SORgenerally prohibitsclaimants frombringing certainclaims againstconstructionprofessionals morethan six years after‘the substantialcompletion ofthe improvementto real property.’Determiningthe ‘substantialcompletion’ datecan sometimesbe difficult.”be unrelated. Under these circumstances, thedefendant bears the burden of establishing thatthe cause of the wrongful construction claimis the same cause underlying the manifestationon which the defendant relies to trigger thelimitations period.39 Thus, in Wildridge Venturev. Ranco Roofing, Inc., the Colorado Court ofAppeals held that the manifestation of onedefect does not trigger the RP-SOL for unrelateddefects that have not yet manifested.40The Court reversed the trial court’s entry ofsummary judgment for the defendant because,DE C E M BE R 2 0 2 0while the plaintiff knew of leaks in eight of its 41buildings more than two years before filing suit,there was a material factual dispute regardingwhether those leaks resulted from the samedefects that formed the basis of the suit.41 TheCourt stated: “Here, although the leaks may havebeen the physical manifestations of some defect,there is a genuine factual dispute as to whetherthe leaks that were known to plaintiff in May 1994resulted from the same defects that formed thebasis of this suit.”42 Because the party assertingthe statute of limitations as an affirmativedefense bears the burden of establishing thatdefense, a defendant asserting the RP-SOLmust establish that any defect manifestationsthat occurred outside the statutory limitationsperiod were caused by the same defects thatform the basis of the suit.43In Broomfield Senior Living Owner, LLCv. R.G. Brinkmann Co., the Colorado Court ofAppeals followed Wildridge Venture’s reasoningand reversed a trial court’s entry of summaryjudgment in favor of a defendant-builder onconstruction defect claims.44 The Court foundthat the trial court improperly disregardedevidence that “different phases of excavation. . . revealed different construction defects overa lengthy period of time,” and a reasonablejury could find that several of these defectsremained latent until within two years of theclaims being filed.45 Therefore, factual disputesremained regarding the discovery date of eachdefect and whether and on what dates anyrepairs were completed.46Triggering the RP-SOR: “SubstantialCompletion of the Improvement”The RP-SOR’s triggering event is the “substantialcompletion of the improvement to real property”that is the subject of a construction defectclaim.47 The RP-SOR does not define substantialcompletion.48 Interpretation of the statutoryterm “substantial completion” is a questionof law, but whether a particular improvementto real property is substantially complete is amixed question of law and fact.49The RP-SOR generally prohibits claimantsfrom bringing certain claims against construction professionals more than six years after “thesubstantial completion of the improvement to

real property.” Determining the “substantialcompletion” date can sometimes be difficult. Incases brought by individual homeowners againstdevelopers or builders of single-family, detachedhomes, this analysis is relatively straightforward and courts often begin by assuming thatthe Certificate of Occupancy (C.O.) suppliesthe relevant “substantial completion” date.50However, substantial completion may occursooner or later than the C.O. date dependingon the facts.51 In cases involving multifamilydwellings integrated within a community, thequestion of when “substantial completion ofthe improvement” occurred is more complex.Multifamily ProjectsWhere multifamily dwellings contain severalbuildings constructed over time, courts mustdetermine when “substantial completion”occurred for claims against a particular construction professional regarding a particulardefect. 52 Unsurprisingly, property ownerswould prefer the RP-SOR to begin running uponsubstantial completion of the last of severalbuildings comprising the project, or the common elements, if completed later. Constructionprofessionals, on the other hand, typicallyargue that the repose period began to run upona particular unit’s or building’s substantialcompletion, or the date they substantiallycompleted their scope of work if it involved morethan one unit, or when a particular buildingwas substantially completed, whichever wouldafford them the greatest protection from suit.Situations involving exterior common areasor construction elements serving multiplebuildings, such as grading or drainage, canbe especially confusing because they may beput into use temporarily, but then expanded,modified, or interconnected as additionalbuildings are completed.Further complicating this issue, it is oftenimpossible to analyze how a particular construction component will perform and whether it isdefective until an entire construction project issubstantially complete. Property owners arguethat applying one repose period for all claimsand damages asserted within a constructiondefect action is consistent with CRS § 13-80104(1)(a)’s use of the word “action,” and thiseliminates the difficulty of applying differentrepose periods to each defect, claim, or scopeof work. Construction professionals, especiallysubcontractors, counter that this approacheffectively extends the repose period for workperformed and/or structures substantiallycompleted long before a multi-building, multiphase project is completed.In Shaw Construction, LLC v. United BuilderServices, Inc. and Sierra Pacific Industries v.Bradbury, discussed immediately below, theColorado Court of Appeals had the opportunityto declare a firm rule for applying the RP-SORto defects manifesting over time in severalbuildings in the same multifamily development.Instead, the Court issued narrow rulings inthese cases and avoided any such broad pronouncement. Although the Colorado SupremeCourt, in Goodman v. Heritage Builders, Inc.,later overruled the main holdings of these twocases on other grounds,53 these cases illustratethe questions pertinent to determining whensubstantial completion occurred for defectclaims arising from multifamily housing developments.In Shaw Construction, LLC, an HOA sued ageneral contractor for defects in a multi-buildingresidential development. The general contractorthen sued several subcontractors for indemnity.54 On appeal regarding the timeliness ofthe indemnity claims, the Court held that adiscrete component of a larger project coulditself be an “improvement” to real property forpurposes of applying the RP-SOR.55 The Courtheld, on the facts before it, that the reposeperiod commenced on a builder’s indemnityclaims against subcontractors who workedon the last completed building in the projectwhen that building’s C.O. issued.56 Althoughthe larger project included “exterior courtyards, sidewalks, alleys, landscape features,and benches” completed after the final C.O.issued, the Court found the date these commonelements were completed irrelevant to theclaims against the subcontractors who did notwork on them.57Shaw Construction, LLC did not reach thequestion whether, for claims against a particularconstruction professional, the RP-SOR beginsto run upon substantial completion of thatconstruction professional’s work or of theimprovement to real property to which suchwork contributed, expressly declining to addresswhether a trade-by-trade approach would beappropriate.58 Since Shaw Construction, LLC,trial courts have continued to be split regardingwhether to employ a trade-specific, building-by-building, or phase-by-phase approachfor subcontractors and other constructionprofessionals who—like the subcontractorsin Shaw Construction, LLC—only worked onsome facets of a larger construction project.59In Sierra Pacific Industries, the ColoradoCourt of Appeals held that the RP-SOR barred aPractice Pointer: CRS § 38-33.3-201(2)CRS § 38-33.3-201(2) provides: “In a common interest community with horizontal unitboundaries, a declaration . . . creating . . . units shall include a certificate of completionexecuted by an independent licensed or registered engineer, surveyor, or architectstating that all structural components of all buildings containing or comprising anyunits thereby created are substantially completed.” (Emphasis added). No reportedcases have construed this statute. Relying on this provision, HOAs may argue thatthe legislature has defined “substantial completion” in the context of condominiumdevelopments to mean substantial completion of all of a development’s buildingsfollowing execution of a certificate of completion. While Shaw involved the issuance ofan architect’s certification of completion, the Court did not “resolve whether substantialcompletion of an entire construction project occurs only when the architect certifiesthe project as complete.” (Shaw Constr., LLC, 296 P.3d at 155.) Moreover, Shaw does notexplain whether the architect’s completion certification there was the type describedby § 201(2).DE C E M BE R 2 0 2 0 C OL OR A D O L AW Y E R 31

FEATURE TITLECONSTRUCTION LAWcontractor’s indemnity claims against a subcontractor where the subcontractor undisputedlycompleted its work in 2002, last made repairsrelating to its work in 2004, and was first suedfor indemnity in 2014, despite the fact thatothers attempted repairs as late as 2011. TheCourt rejected the suggestion that “substantialcompletion” as to claims against the defendantsubcontractor occurred when others beside thedefendant ended their later repair attemptson the same building improvement, stating“a subcontractor has substantially completedits role in the improvement at issue whenit finishes working on the improvement.”60The Court did not explain precisely what itmeant by this statement,61 and the ColoradoSupreme Court later overruled the case onother grounds.62 Sierra Pacific Industries didnot decide whether the substantial completiondate should be measured from completion ofthe last building on which the subcontractorworked or from completion of the last discretecomponent on which it worked because, likein Shaw Construction, LLC, under the Court’slater-overturned analysis the claims wouldhave been barred even if the Court had usedthe C.O. date of the last building the defendantworked on.63Per Project, Per Phase, Per Building, PerUnit, Per Construction Professional, PerScope of Work, or Something Else?Colorado’s district courts have taken varying approaches to applying the RP-SOR to multi-phase,multi-building, multifamily developments.These courts have struggled with whetherthe “improvement” to real property shouldbe deemed substantially complete when thebuilding containing the defect is substantiallycomplete, when the development as a wholeis substantially complete, when the particulardefendant’s scope of work is completed, oron some other date.64 Even when applying abuilding-by-building analysis, these courts havedistinguished between developers, builder-vendors, and general contractors, who typically haveresponsibilities relating to the multi-buildingproject as a whole, and subcontractors andtradesmen, who frequently have responsibilitieson a building-by-building basis. These courts32 C OL OR A D O L AW Y E R often find that the RP-SOR does not begin to runagainst the former (development) group untilthe project as a whole is substantially completed,and sometimes hold the repose period beginsto run as to the latter (subcontractor) groupupon completion of their entire scope of workif it spans several buildings.In one case, a district court held that therepose period began to run on claims assertedagainst a developer and general contractorregarding a common-interest developmentwhen the 26-building, 71-unit project as awhole was completed, following issuanceof the last unit’s C.O.65 The court noted thatthe defendants’ interpretation of the statute,which would result in 71 different substantialcompletion dates triggering 71 different reposeperiods (one for each unit), would “frustratethe purpose for resolving the defects throughthe [notice of ] claim process and completelydisrupt judicial proceedings.”66 The court heldthat “the language of the statute contemplatesa singular, distinct point in time when theimprovement is substantially completed.”67Some argue the repose period begins torun as to a particular construction professionalon the date that construction professionalcompleted its scope of work on the allegedlydefective improvement. Property owners oftenrespond that the RP-SOR refers only to “substantial completion of the improvement to realproperty,” rather than separate completion ofeach of several discrete activities leading up tosubstantial completion. Some courts outsideColorado have used the completion date fora project, rather than its constituent parts,as the trigger date for the commencement ofthe applicable repose period,68 while othercourts have used completion of the particulardefendant’s work, usually when the state statuteexpressly ties the repose period trigger to aparticular subcontractor’s work.69community roads; and exterior plumbing,sewage, or irrigation systems. At least twodistrict courts have concluded that the reposeperiod for exterior grading and drainage workdoes not run on a building-by-building basisbut should be treated as an integrated wholeproperty improvement upon completion of theentire project’s grading and drainage.70Common AreasThe “substantial completion” issue becomesmore complicated if the defective elementis a common area that serves more than onebuilding and whose construction continuesthroughout the project’s construction as a whole.Examples include surface grading or drainage;NOTE SDE C E M BE R 2 0 2 0ConclusionSince 2005, Colorado’s appellate courts haveprovided some needed direction regardingdiscrete RP-SOL and RP-SOR issues, suchas t

The RP-SOL and RP-SOR apply broadly to most construction professionals involved in real estate development and construction. They do not apply to a non-commercial This article examines significant changes in and clarifications to the law since 2005 interpreting and applying Colorado's real property improvement statutes of limitation and repose.