Transcription

mdrcP O L I C YB R I E FBUILDING KNOWLEDGETO IMPROVE SOCIAL POLICYM A Y2 0 1 3Enhancing GED Instructionto Prepare Students forCollege and CareersEARLY SUCCESS IN LAGUARDIA COMMUNITY COLLEGE’SBRIDGE TO HEALTH AND BUSINESS PROGRAMBy Vanessa Martin and Joseph BroadusNationwide, close to 40million adults lack a highschool diploma or a General EducationalDevelopment (GED) credential.1 Nearly aquarter of high school freshmen do notgraduate and, in many large cities, dropoutrates in recent years have stood at around50 percent.2 And while most high schooldropouts eventually do continue theireducation — usually through adulteducation or GED preparation programs— too few of those who start GEDprograms ever pass the exam. Moreover,for those who do earn their GED, thecertificate often marks the end of theireducation, in part because few GEDprograms (even those that operate oncommunity college campuses) are welllinked to college or training programs.Students with only a high school diplomaalready face long odds of success in a labormarket that increasingly prizes specializedtraining and college education; for GEDholders, the chances are even worse.3 Giventhis context, the need to develop strongerpathways to college for those without highschool credentials is clear. And this need isonly magnified by new rules eliminatingfederal financial aid for aspiring collegestudents without a high school diploma ora GED, and by the planned 2014implementation of a new GED exam thatemphasizes college readiness.4To better understand how adult educationprograms might strengthen pathways tocollege and careers, MDRC, with financialsupport from the Robin Hood Foundationand MetLife Foundation, partnered withLaGuardia Community College of the CityUniversity of NewYork (CUNY) tolaunch a small butThe need to developrigorous study ofstronger pathwaysthe GED Bridgeto college for thoseto Health andwithout high schoolBusiness program.credentials is clear.The GED Bridgeprogram representsa promising newapproach to GED instruction, as it aims tobetter prepare students not only to passthe GED exam, but also to continue on tocollege and training programs. MDRC hasconducted several evaluations of programsthat include GED preparation as oneamong many program components, butthis evaluation is one of only a few to focusspecifically on GED curriculum, programdesign, and efforts to forge a stronger linkto college and career training. The resultsare highly encouraging: One year after

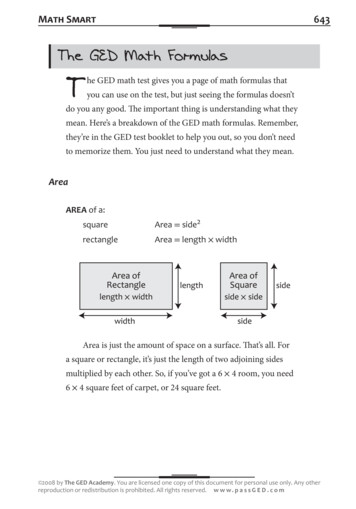

MDRC POLICY BRIEFenrolling in the program, Bridge studentswere far more likely to have completed thecourse, passed the GED exam, and enrolledin college than students in a more traditionalGED preparation course. This brief detailssome of the key findings from this study aswell as their implications for future researchand for the development of stronger GEDand adult education programming.TEACHING THE GEDThe GED exam takes over seven hoursto complete and consists of subtests infive content areas: mathematics, reading,science, social studies, and writing. Due todifferences in state requirements and thewide range of programs available, there is noconsistent standard for GED test preparationand instruction; students can prepare for theexam in a number of ways. Ina GED Testing Service study ofLaGuardia’s GED over 90,000 people who took theBridge to Health and GED exam in 2004, roughly halfof the study sample participatedBusiness program was in a preparatory program ofdesigned explicitly as a some kind.5 These kinds ofpathway to college adult education programsand careers. are often operated by highschools, community colleges, orcommunity-based organizations.Most often, the instructors workpart time and may not have had training inadult education methods. Lessons are unlikelyto be organized around any particular themes,and instruction is generally limited to buildingthe skills necessary to pass the exam. Thereis often little intention or ability to assiststudents in preparing for the next step in theireducation or career.62LaGuardia’s GED Bridge to Health andBusiness program — described in detailbelow — offers critical enhancements to thistraditional approach. Rather than focusingsolely on passing the test, the programwas designed explicitly as a pathway tocollege and careers. The program includesan original, interdisciplinary curriculumthat integrates material from the fieldsof health care and business. In addition,students attend more hours in class over thecourse of a semester than is typical for GEDprograms and receive intensive advisingfrom full-time Bridge staff.THE BRIDGEPROGRAMThe foundation of the GED Bridge programis its “contextualized curriculum.” Thecurriculum has two broad goals: first, to buildthe skills that are tested on the GED examthrough the use of content specific to a fieldof interest (health care or business) and,second, to develop general academic habitsand skills that prepare students to succeedin college or training programs. The first ofthese goals is approached by using originalmaterial related to issues and themes specificto a career track to teach concepts that will betested on the exam. Rather than developingmath, writing, and reading comprehensionskills through generic exercises, studentslearn by using materials specific to the healthcare or business track they are consideringpursuing. The purpose is not for the courseto simultaneously function as a GEDcourse and an introductory health care orbusiness course, but rather to introducebroad concepts, using career-relevant andthus more engaging materials while alsoallowing students to consider a career in thefield in a deliberate and informed manner.The second goal of the curriculum — andof the program — is to prepare students forthe academic challenges of college and thedemands of the workplace. This is done by

MAY 2013structuring lessons and class expectationsso that they mirror the assignments andexpectations students are likely to face incollege: Students receive a syllabus for thesemester, get regular homework, and areencouraged to spend as much — or more —time on out-of-class work as on in-class work.Likewise, the instructors emphasize analyticalwriting and critical thinking exercises in theirassignments to prepare students for theinstructional environment they are likely toencounter in a college classroom.Finally, Bridge students receive individual andgroup advisement inside and outside of class,providing them with an opportunity to explorecareer options, complete career-interest andskills inventories, do research into local growthindustries and postsecondary educationaloptions, and develop plans for their educationaland professional growth. Beginning in thesecond week of the course, a transitions adviserleads regular in-class activities on setting goals,the costs and benefits of higher education, andcollege registration. Health and businesscollege faculty also visit the classroom to speakwith students about their programs and thenature of the work in their fields.T H E E VA L U AT I O NMDRC used a random assignment designto evaluate the effects of the GED Bridgeprogram on student achievement comparedwith a more traditional GED program (GEDPrep) modeled on LaGuardia’s preexisting,tuition-based GED program.7 After learningabout the study and agreeing to participate,interested and qualified students wereassigned at random to either the GED Bridgeprogram in health care or business — theGED Bridge group — or to a GED Prep course.Tuition was free for both the GED Bridge andGED Prep participants. Table 1 shows keydistinctions between the two programs.A random assignment design can provideunusually reliable information about whatdifference — or “impact” — a programmakes. Because assignment to the researchgroups is random, differences betweengroups in students’ motivation andbackground characteristics are minimized,thus allowing for a truer measure of aprogram’s effects. The study examinesnot only whether participants receive theirGEDs and enroll in college and training,but also whether they stay in college orTABLE 1. Key Distinctions Between GED Bridge and GED PrepPROGRAM COMPONENTGED BRIDGEGED PREPINSTRUCTIONFull-time instructor, paid for classpreparation timeAdjunct instructor, paid for in-class time onlyIN-CLASS TIME108 hours over 12 weeks60 hours over 9 weeksCareer-oriented curriculum featuring originalmaterialsGED textbook assignmentIn-class and individualized transitioncounselingNone beyond general college resourcesCURRICULUM ANDMATERIALSCOUNSELING AND SUPPORT3

MDRC POLICY BRIEFTABLE 2. Selected Characteristics of Study Participants at BaselineCHARACTERISTICSSTUDY SAMPLEFEMALE (%)67.2AVERAGE AGE26.6RACE/ETHNICITY (%)HISPANIC/LATINOAFRICAN-AMERICAN, NON-HISPANIC/LATINOOTHER50.134.515.4RECEIVING PUBLIC ASSISTANCE (%)53.4EMPLOYED AT TIME OF RANDOM ASSIGNMENT (%)38.4STARTING TABE SCORE (%)7TH-GRADE LEVEL8TH-GRADE LEVEL9TH-GRADE LEVEL10TH-GRADE LEVEL OR ABOVE24.925.216.333.6HIGHEST GRADE ATTAINED (%)9TH GRADE OR BELOW10TH GRADE11TH GRADE12TH GRADENOT KNOWN15.230.136.38.99.5SAMPLE SIZE369SOURCE: MDRC calculations from GED Bridge study enrollment data.training programs. Findings on studentachievement are based on GED Bridgeprogram participation data, New York StateGED Status Reports, GED test administrationdata, and LaGuardia Community College’sManagement Information System (MIS) data.THE PARTICIPANTS4The GED Bridge program was targeted tolow-income individuals in New York Citywho did not have a high school diploma ora GED. In order to qualify for the program,participants had to score at a seventh-gradereading level or above on the TABE (Test forAdult Basic Education). This requirement waslower than that of many GED preparationprograms because the program was explicitlyaiming to make the GED and college moreaccessible to those with lower literacy levels.8Participants also had to be 18 years of age orolder and have an income below 200 percentof the federal poverty level.The recruitment and enrollment process for theGED Bridge program was fairly intensive, lastingabout three to five weeks before the beginningof each semester. Potential participants filledout an application, took the TABE to determinetheir eligibility and reading levels, and completeda writing sample and an interview to signaltheir commitment and interest. Once they weredetermined eligible and appropriate for theprogram, they were asked to provide writtenconsent that they wanted to participate in thestudy. Then they received their assignment toeither the GED Bridge or the GED Prep group.Table 2 shows selected characteristics ofthe full research sample, which consistsof 369 participants who were enrolled inthe study over four semesters — fall 2010,spring 2011, fall 2011, and spring 2012. A fewcharacteristics in particular stand out: Over80 percent of students were either AfricanAmerican or Hispanic, about half of thestudents scored at a seventh- or eighth-gradereading level on the TABE, over half reportedreceiving some form of public assistance, andclose to 40 percent reported that they wereemployed when they began the program.KEY OUTCOMESThis analysis covers only the first threecohorts — fall 2010, spring 2011, and fall 2011— representing a sample of 276 participants.Data on the spring 2012 cohort are not yetavailable. However, since the program was

MAY 2013implemented consistently for every cohort,and each cohort had roughly the samenumber of participants, it is likely that theresults will be similar when the fourth cohort(spring 2012) is added to the analysis. Compared with students who wentthrough the traditional GED Prep course,Bridge students were much more likely tocomplete the course. The first milestonefor students in the GED Bridge programis course completion. As illustrated inFigure 1, students in the GED Bridge groupcompleted the course at a significantlyhigher rate than the Prep students (68percent compared with 47 percent). Bridge students were far more likely topass the GED exam.9 GED Bridge studentswere more than twice as likely to pass theGED exam as GED Prep students: overall,53 percent of Bridge students passed theexam within 12 months after enteringthe study, compared with 22 percentof Prep students, as shown in Figure 1.As expected, a large majority of thesestudents passed the GED exam in the firstsix months after completing the course— 44 percent in GED Bridge comparedwith 20 percent in GED Prep (a differencestatistically significant at the 1 percentlevel, not shown). The difference betweengroups continued to grow over time, asFIGURE 1. 12-Month Impacts on Course Completion, GED Pass Rates, and College Enrollment68.2Completed GED Course46.5Impact 21.7***52.8Passed GED exam22.4Impact 30.4***24.1Ever enrolled at a CUNYcommunity college7.2Impact 17***GED Bridge groupGED Prep group11.5Enrolled at CUNY fora second semester2.60Impact 8.9***10203040Percentage of sample members5060SOURCES: MDRC calculations using GED Bridge participation data, New York State GED Status Reports, CUNY MIS data, and GED test administration data.NOTES: Figure includes sample members from the fall 2010, spring 2011, and fall 2011 cohorts. All outcomes presented in Figure 1 are calculated basedon all 276 sample members in the first three cohorts. Statistical significance levels are indicated as follows: *** 1 percent; ** 5 percent; * 10 percent.Estimates were regression-adjusted using ordinary least squares, controlling for cohort, age, gender, race, starting TABE score, public assistance receipt, andemployment. Rounding may cause slight discrepancies in calculating sums and differences. A two-tailed t-test was applied to differences between outcomes forthe program and control groups.705

MDRC POLICY BRIEFBridge students were also more likelythan Prep students to pass the GED exambetween 7 and 12 months after study entry— 9 percent of Bridge students passedduring those months, compared with 3percent of Prep students (a differencestatistically significant at the 5 percentlevel, not shown).6 Bridge students enrolled in college at muchhigher rates than students in the traditionalGED Prep course. As shown in Figure 1,GED Bridge students were more thanthree times as likely to enroll in a CUNYcommunity college as GED Prep students:Only 7 percent of GED Prep studentsenrolled compared with 24 percent of GEDBridge students, a statistically significantdifference of 17 percentage points.10 Thesedata reveal another interestingfinding, not shown in the figure:GED Bridge students While most of the GED Bridgestudents who enrolled at CUNYwere more than three did so in the first semester aftertimes as likely to enroll the GED course, over one-thirdin a CUNY community of those who enrolled did so incollege as Prep students. the second semester after theGED course — and they weremore likely to enroll at eithertime than those in the GEDPrep group. In addition, Bridge studentspersisted in college at a higher rate thanPrep students: 12 percent of all Bridgestudents enrolled in the first semester aftercompleting the Bridge course and thenalso continued into the second semester,compared with only 3 percent of Prepstudents. This is the only college retentionmeasure available at this time. Longer-termfollow-up data will be presented in a laterbrief, which will include the fourth and finalstudy cohort.FINDINGS FROMTHE FIELDIn the context of this study, it is impossible toisolate any single component or combinationof components as the critical pieces inthe Bridge program’s apparent success.But numerous visits to the program byMDRC researchers between fall 2010 andspring 2012 — including interviews withstaff members, observations of classroomand counseling activities, and focus groupdiscussions with students in both Bridgeand Prep — yielded a few key findings abouthow the staff implemented the Bridge modeland how students in both Bridge and Prepfelt about their experiences. It is likely thatat least some of the impact results can betraced to these findings. Original materials and lesson plans in theBridge course employed critical thinkingskills and emphasized core conceptsfrom the fields of business and healthcare. Throughout the evaluation, Bridgestaff developed and refined an originalcurriculum consisting of a number ofprimary source materials designed to buildreading, writing, and math skills througha focus on health care or business. Eachsemester, Bridge students were assigneda book focused on central concepts fromthe health and business fields. Healthcare students, for example, read anddiscussed issues of medical ethics anddecision making in First, Do No Harm,a book detailing the ethical dilemmasthat doctors, nurses, and families facedwhen working with patients in a Texashospital. Beyond these readings, dailyclass activities revolved around basicconcepts that professionals in the fieldwould have to consider, and studentswere asked to engage critically with texts

MAY 2013and assignments from the perspective ofprofessionals in their field. An example ofone such classroom activity appears below.This consistent attention to the conceptsof the field represented a marked contrastfrom the disconnected exercises that wereused in the traditional GED course. As oneparticipant put it, “The thing that’s mostmotivating is that everything we’re doingis [about] health. It’s getting us intosomething that we want to do. Being in aregular GED course isn’t the same.” Bridge students benefited from full-time,consistent, qualified program staff andadditional in-class hours. The Bridgeprogram staff consisted of full-time,master’s-level educators trained in adultliteracy instruction and contextualizedcurriculum development. Staff members’full-time status allowed themtime to develop curricula andlesson plans collaboratively,“The thing that’s mostoffer support to studentsmotivating is thatoutside of class hours, andeverything we’re doingimplement the program’selements in a robust fashion. is [about] health.By contrast, Prep instructors, It’s getting us intoas adjunct faculty, were paid something that wean hourly wage solely forwant to do. Being inthe time they spent in thea regular GED classclassroom. And althoughsome of them indicated that isn’t the same.”they had a background inCONTEXTUALIZING READING COMPREHENSIONAs the class begins, a group of about 20 students, mostly African-American andLatina women, sit at circular tables in groups of 3 to 4. The instructor begins theclass by reminding the students that a second essay draft is due in the next classmeeting. He also reminds them to read their textbook chapter on disease.The instructor hands out the first assignment for the day: a New York Times articledescribing a South African hospital that is housing quarantined tuberculosispatients. The article discusses the experiences of patients, doctors, and familymembers, as well as policy decisions surrounding the quarantine. The students readthe article and spend 10 minutes quietly writing about the issues and dilemmas thatcome up for patients and health care professionals when dealing with the disease.After the students have written their short reflection essays, the instructordistributes large sheets of paper for the groups to write out the issues theyidentified and then share them with the class. Half the groups are instructed toidentify issues from the patient’s perspective; half are instructed to identify issuesfrom the health care professional’s perspective. The groups discuss the issues fromthe article as the instructor passes among the students to listen.The instructor asks the groups to share the issues that they identified, beginningwith issues that arise for the health care professional. The class listens attentivelyas a woman lists and explains issues. The instructor asks her probing questionsabout how each issue arises. The class then moves on to groups with the patient’spoint of view.7

MDRC POLICY BRIEFadult education, they received little or notraining directly related to their positioninstructing Prep students. Probablyfor reasons related to this difference,the Bridge instruction staff remainedconsistent over the course of the evaluation(allowing the staff to apply lessons fromone semester to the next), while therewas considerable turnover among Prepinstructors over the semesters. One Prepinstructor, describing the frustration of nothaving more paid time to design originallesson plans and work withstudents, acknowledged that “all“When you miss a class, I’ve really done is played nannywith the GED book.” Several[the instructor] will take Prep instructors described athe time to bring you up similar feeling that their paidto speed. In other classes, time did not allow them toyou miss a lesson, that’s prepare for class thoroughly oryour business.” meet with students outside ofclass hours.8Bridge students also benefitedfrom additional in-class hours. Studentsin both groups repeatedly pointed tothese differences in class time andpersonal attention as critical elements intheir experience. Many students in GEDPrep complained of how little in-classtime they had to prepare for the exam,with one student summing up a generalfeeling: “I wish we had more days. Wehave so little time to stuff ourselves withso much information.” Bridge studentsoften observed the opposite, describingthe time commitment as “about right” andcelebrating the staff’s willingness to “takethe time” when working with students. Asone put it, “they take the time to help usin making that transition”; another said,“when you miss a class, [the instructor]will take the time to bring you up to speed.In other classes, you miss a lesson, that’syour business.” Postsecondary transition advisementwas well incorporated into the studentexperience. Bridge students had regularmeetings with a transitions adviserand were more aware of requirementsto enter college and training programsthan Prep students. In keeping withone of the program’s central goals,transition advisement was integrated withthe classroom experience. An adviserroutinely visited the classroom to discussthe transitions process, assist studentswith their research into college andcareer programs, and remind studentsof upcoming events or deadlines. Theadviser also met individually with studentsto discuss educational and career goals.Further, speakers from the businessand health care faculty at LaGuardiaspoke to Bridge classes about what theycould expect in college. This emphasisappeared to give the Bridge students anadvantage over Prep students in thinkingabout their next steps: during focusgroups, the Bridge students consistentlydemonstrated greater knowledge aboutdeadlines and college applicationrequirements than Prep students. Overall, Bridge students appeared moreengaged in the classroom and moreencouraged by the program experience.Probably thanks to the effective integrationof the program components alreadydescribed, Bridge students consistentlydemonstrated more engagement with theirclassmates and with course material, andwere generally more excited about their

MAY 2013program experience than Prep students.While Bridge students talked freely amongthemselves and referred to classmates as“my family” on multiple occasions, Prepstudents tended to interact less frequentlyduring classes and focus group discussions.Likewise, although the majority of studentsin both groups were hopeful about theirfutures, Bridge students spoke morefrequently and directly about the program’sinfluence on their thoughts and plans forthe future. One business student, reflectingon the transitional emphasis, said, “If you’dhave asked me five years ago, I’d have said‘no, I’m not going to college,’ but . when Igot here, I got the vibe: [college] is the placeI need to be.”I M P L I C AT I O N SFOR POLICYAND PRACTICEWith national interest growing in programsthat prepare individuals for careers in highgrowth industries, and with changes comingto the GED exam, these promising findingscould hardly come at a better time. Theycontribute to a growing body of evidencethat sector or career-based initiatives mayoffer an effective route for low-income, lowskilled adult learners to complete secondaryeducation and gain access to highereducation and training. While LaGuardiachose health care and business as its careertracks — because those industries havehigh growth potential in New York City andbecause there is particular interest in thosefields among students — field researchsuggests that the success of the program didnot hinge on the career paths per se. Rather,the Bridge program’s success depended onthe integration of key program components,particularly the use of course materials thatwere relevant to student aspirations, stronginstruction, and proactive advisement toguide students on to the next step in theireducation.It will be important to continue to followGED Bridge students over the next fewyears to learn how well their collegepersistence holds upcompared with GED Prep“If you’d have asked mestudents. While the Bridgeprogram succeeded in thefive years ago, I’d havevital task of increasing accesssaid ‘no, I’m not goingto college for its students,to college,’ but . whenmany Bridge students stillI got here, I got the vibe:had to take remedial classes[college] is the placeupon entering LaGuardia,and college persistence ratesI need to be.”for remedial students aregenerally quite low.11 The studyat LaGuardia faced the obvious limitationsof a small sample size and the fact that onlya single community college was operatingthe program, so moving forward it will beimportant to understand how well thisor similar models can be implementedelsewhere. Nonetheless, the program’sdramatic impacts on GED pass rates and oncollege enrollment and persistence suggestthat the model holds considerable promisefor strengthening the links between lowincome students who need to complete theirsecondary education and college or skillstraining programs. Ultimately, continuedstudies of this and similar models —preferably at a scale sufficient for researchersto better determine for whom the programworks best — would provide an even clearerpicture of how to strengthen GED and adulteducation for low-income people.9

MDRC POLICY BRIEFNOTES3 Tyler (2005).Adelman, Clifford. 2004. Principal Indicators ofStudent Academic Histories in Post-SecondaryEducation, 1972-2000. Washington, DC: Instituteof Education Sciences, U.S. Department ofEducation.4 The new GED exam, planned for release in2014, will “measure a foundational core ofknowledge and skills that are essential for careerand college readiness.” GED Testing Service(2012b); Fain (2012).Bailey, Thomas. 2009. “Challenge andOpportunity: Rethinking the Role and Functionof Developmental Education in CommunityCollege.” New Directions for Community Colleges,2009: 11-30.5 McLaughlin, Skaggs, and Patterson (2009).Bailey, Thomas, Dong Wook Jeong, and SungWoo Cho. 2010. “Referral, Enrollment, andCompletion in Developmental EducationSequences in Community Colleges.” New York:Community College Research Center, TeachersCollege, Columbia University.1 GED Testing Service (2012a).2 Stillwell and Sable (2013); Swanson (2009).6 Beder and Medina (2001).7 Since 2010, the GED tuition program atLaGuardia has implemented new instructionalpractices; the Prep classes were kept in place forstudy participants through spring 2012.8 For this and other reasons, the resultspresented here are not comparable to GEDstatistics that may appear in other reportson GED outcomes. GED outcomes are oftencalculated by dividing the number of those whopassed the GED exam by the number who took it,or by the number who completed a GED course.Results here are shown for everyone who enrolledin the study.9 The GED pass rates reported here are for thefull study sample, including people who left theircourse after enrolling or who completed theircourse but never took the test.10 MDRC’s review of CUNY enrollment suggeststhat most if not all of the study sample memberswho enrolled in CUNY enrolled at LaGuardiaCommunity College.11 Adelman (1999, 2004); Bailey (2009); Bailey,Jeong, and Cho (2010).REFERENCES10Adelman, Clifford. 1999. Answers in the Toolbox:Academic Intensity, Attendance Patterns, andBachelor’s Degree Attainment. Washington, DC:Office of Educational Research and Improvement,U.S. Department of Education.Beder, Hal, and Patsy Medina. 2001. ClassroomDynamics in Adult Literacy Education. NCSALLReports #18. Cambridge, MA: National Center forthe Study of Adult Learning and Literacy, HarvardUniversity Graduate School of Education.Fain, Paul. 2012. “One-Stop Shop.” Inside HigherEd. Web site: www.insidehighered.com.GED Testing Service. 2012a. 2011 Annual StatisticalReport on the GED Test. Washington, DC: GEDTesting Service, American Council on Education.GED Testing Service. 2012b. “The NewAssessment Is a Stepping Stone to a BrighterFuture.” Web site: .McLaughlin, Joseph W., Gary Skaggs, andMargaret B. Patterson. 2009. Preparation forand Performance on the GED Test. Washington,DC: GED Testing Service, American Council onEducation.Stillwell, Robert, and Jennifer Sable. 2013.Public School Graduates and Dropouts from theCommon Core of Data: School Year 2009-2010.First Look (Provisional Data). Washington, DC:National Center for Education Statistics, Instituteof Education Sciences, U.S. Department ofEducation.

MAY 2013Swanson, Christopher B. 2009. Cities in Crisis2009: Closing the Graduation Gap: Educational andEconomic Conditions in America’s Largest Cities.Bethesda, MD: Editorial Projects in Education, Inc.Tyler, John H. 2005. “The General EducationalDevelopment (GED) Credential: History, CurrentResearch, and Directions for Policy and Practice.”Chapter 3 in John Comings, Barbara Garner, andChristine Smith (eds.), Review of Adult Learningand Literacy, Volume 5: Connecting Research Policyand Practice: A Project of the National Center forthe Study of A

with a more traditional GED program (GED Prep) modeled on LaGuardia's preexisting, tuition-based GED program.7 After learning about the study and agreeing to participate, interested and qualified students were assigned at random to either the GED Bridge program in health care or business — the GED Bridge group — or to a GED Prep course.