Transcription

TACIRPublication PolicyReports approved by vote of the Tennessee Advisory Commission onIntergovernmental Relations are labeled as such on their covers with thefollowing banner at the top: Report of the Tennessee Advisory Commission onIntergovernmental Relations. All other reports by Commission staff are preparedto inform members of the Commission and the public and do not necessarilyreflect the views of the Commission. They are labeled Staff Report to Membersof the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations on theircovers. TACIR Fast Facts are short publications prepared by Commission staff toinform members and the public.Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations226 Capitol Boulevard Building · Suite 508 · Nashville, Tennessee 37243Phone: 615.741.3012 · Fax: 615.532.2443E-mail: tacir@tn.gov · Website: www.tn.gov/tacir

Report of the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental RelationsTennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of LivingTyler Carpenter, M.P.A.Research Associate David W. Lewis, M.A.Research Manager Lynnisse Roehrich-Patrick, J.D.Executive Director Cliff Lippard, Ph.D.Deputy Executive Director Teresa GibsonWeb Development & Publications ManagerJanuary 2016

Recommended citation:Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. 2016. Tennessee’s HomesteadExemptions Adjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of Living. s/2016HomesteadExemption.pdf.Tennessee Advisory Commission on IntergovernmentalRelations. This document was produced as an Internetpublication.

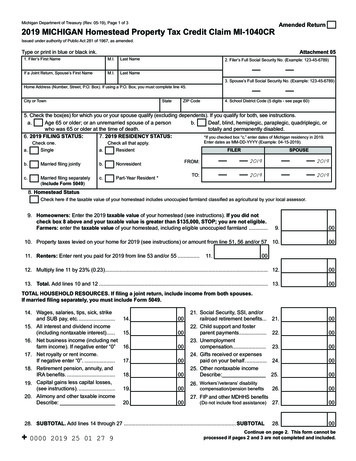

226 Capitol Boulevard Bldg., Suite 508Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0760Phone: (615) 741-3012Fax: (615) 532-2443www.tn.gov/tacirTO:Commission MembersFROM:Lynnisse Roehrich-PatrickExecutive DirectorDATE:6 January 2016SUBJECT:Adjusting the Homestead Exemption to Reflect Cost of Living (Public Chapter326, Acts of 2015)—Final Report for ApprovalThe attached Commission report is submitted for your approval. The report responds to PublicChapter 326, Acts of 2015, requiring the Commission to study the homestead exemptionamounts in Tennessee and determine whether they should be increased to accurately reflectthe cost of living. The act also requires the Commission to compare the various categories ofhomestead exemptions in detail to those of other states. The report provides a brief history ofthe homestead exemption in Tennessee, compares the homestead exemptions of all states,and examines the homestead exemption in the context of other available propertyexemptions.Tennessee has the lowest homestead exemption of the states that do not allow the use of thefederal homestead exemption and has the third lowest combined dollar value of all propertyexemptions after Missouri and Alabama. The homestead exemption amounts in Tennessee forindividuals ( 5,000) and joint owners ( 7,500) have lost considerable value and would be worth 18,513 and 21,907 if they had kept pace with inflation. A simpler way to bring these figuresup to date and keep them up to date would be to adopt an individual state homesteadexemption amount equal to the federal homestead exemption, which is adjusted for inflationevery three years. Tennessee’s exemption amounts for debtors with custody of a minor childare currently more than those amounts and would need to be grandfathered until the federalexemption amount catches up to it.

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of LivingContentsTennessee’s Homestead Exemptions—Should They be Updated?.1The Homestead Exemption—Attempts to Balance the Interests of Debtors and Creditorsin Tennessee and Other States.5Bankruptcy reform in the 1970s.8Tennessee’s high bankruptcy rates.8Balancing the interests of debtors and creditors in bankruptcy. 12Exemptions as protection against the forced sale of assets. 13Homestead exemptions in Tennessee and other states. 15Attempts to update Tennessee’s homestead exemptions. 16Comparing Tennessee’s homestead exemptions to those in other states. 19References.29Persons Contacted.31Appendix A. Public Chapter 326, Acts of 2015.33Appendix B. American Bankruptcy Institute: Bankruptcy Filings January throughNovember 2015.35Appendix C. Comparison of Federal Bankruptcy Chapter 7 and Chapter 13.37Appendix D. United States Department of Justice Summary of Bankruptcy Chapters.39Appendix E. Comparison of Federal and Tennessee Bankruptcy Exemptions.41Appendix F. Homestead Exemption as a Percentage of Median Housing Pricesin Tennessee and the US, 1975 through 2014.43Appendix G. Homestead Exemption in Tennessee Bankruptcy (Public Chapter 326, Actsof 2015)—Panel Discussion.45Appendix H-1. Comparison of States’ Sets of Exemptions (Alphabetical Order).49Appendix H-2. Comparison of States’ Sets of Exemptions (Ascending Order by Realand Personal Property Individual Exemptions).59WWW.TN.GOV/TACIRi

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of LivingTennessee’s Homestead Exemptions—ShouldThey be Updated?State laws protecting certain property from the claims of creditors dateback to the early 1800s. Called exemption laws, their goal is to ensure thatdebtors are not left destitute when they fall on hard times. These lawsprotect both real and personal property. Real property protections arecalled homestead exemptions and typically protect a certain amount ofequity held in an individual’s primary residence but in some states protectthe entire residence regardless of its value. Whatever the amount protected,it is exempt from judgments that would otherwise allow creditors to forcethe sale of the debtor’s property.These laws have always been controversial, and the items and amountsprotected have been debated for as long as the exemptions have existed.An example of how they operate from a working paper published by thelaw school of the University of Chicago illustrates why:A creditor lends 1,000 to a debtor, and that debtordefaults on the loan. Under ordinary contractprinciples, the creditor could sue the debtor for breachof contract, obtain a judgment, and then have a localofficial seize assets of the debtor, which would be soldwith the proceeds going to the creditor to the extent ofits claim. Suppose that the debtor’s only valuable assetis an automobile worth 2,000, and the relevant propertyexemption law says that a debtor’s automobile is anexempt asset up to a value of 2,500. Then the localofficial would refuse to liquidate the creditor’s claimby seizing the automobile. The creditor’s claim wouldcontinue to be valid, and the creditor could enforce itagainst any nonexempt assets that the debtor mightsubsequently obtain. The creditor would in most statesbe able to garnish a portion of the debtor’s wages. Butthe automobile would be safe.Exemption lawshave always beencontroversial, and theitems and amountsprotected have beendebated for as long asthe exemptions haveexisted.A debtor cannot agree to waive exemption laws inreturn for a lower interest rate: like usury laws,exemption laws supply mandatory, rather than default,rules. However, exemption laws can sometimes becircumvented, albeit imperfectly, through securityinterests and other arrangements. If, in our example,WWW.TN.GOV/TACIR1

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of Livingthe creditor had obtained a security interest in theautomobile when it lent the 1,000 to the debtor, defaultwould give the creditor the right to seize the automobileand sell it in satisfaction of its claim.1When debtors’ homes aresold to repay unsecureddebt, they are entitledto the lesser of thehomestead exemptionamount or the amount ofequity they have in theproperty.The homestead exemption works the same. A sale of the asset—the caror the home or any property—can be forced if it is worth more than theexempt amount. If it is sold, the debtor is entitled to the lesser of theexempt amount or the amount of equity the debtor has in the property. Inthe case of a home or other property used as collateral for a loan, includinga mortgage, the loan contract determines whether and how the sale can beeffected. This is the case for any judgment including bankruptcy. Althoughthe exemptions can be used to protect property from any judgment, theyare most often used in bankruptcy proceedings. In fact, debtors sometimesfile bankruptcy to protect their property from other types of judgments.Bankruptcy law allows debtors to either completely discharge theirunsecured debt or repay a portion of it based on their ability to pay. Bothoptions are intended to provide honest but unfortunate debtors a freshstart and avoid making them destitute while allowing creditors to recoverat least a portion of the money owed. In order to accomplish this, bothstate and federal laws exempt certain assets from the claims of creditorswhile providing creditors with some protections. While bankruptcy lawshave been around for centuries, they became more important as consumerlending changed in the 1950s and 1960s with the advent of credit cards andthe transition from local personal lending to transactions no longer limitedby location.With expanding credit operations came greater risk for lenders, and thesecompanies began feeling constrained by state usury laws, which cappedinterest rates, limiting the companies’ ability to moderate risk. In the1978 US Supreme Court case of Marquette National Bank of Minneapolis v.First Omaha Service Corporation, the Court held that state anti-usury lawsregulating interest rates could not be enforced against nationally charteredbanks based in other states, freeing those banks to offer credit cards toanyone anywhere. After the Marquette ruling, many states increasedor eliminated their usury limits in order to compete for the business ofnational lenders and level the playing field for their own state-charteredbanks.Around the same time as the Marquette ruling, Congress passed theBankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, which was the largest change in thebankruptcy code since 1898 and eased the process of filing for Chapter13—the chapter used to reorganize and repay unsecured debt. Until then,12Posner et al. 2001, p. 2.WWW.TN.GOV/TACIR

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of LivingChapter 7—the law through which assets are sold to repay debt—wasthe only alternative available to most debtors. The act also listed a setof exemptions for debtors, including a homestead exemption, which isdesigned to protect some of the equity that people have in their primaryresidence. More recently, Congress shifted the balance of protectionstoward creditors when in 2005 it passed the Bankruptcy Abuse Preventionand Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA) setting up additional precautionsagainst debtor abuse and placing limitations on filers. The same yearCongress passed its Bankruptcy Reform Act, Tennessee enacted legislationincreasing its homestead exemption, which had remained unchanged at 1,000 for over 100 years, to 5,000 for individuals. Two years later, theGeneral Assembly added an exemption of 7,500 for joint property owners.Although several attempts have been made to update these amounts, theyhave not been adjusted since and are currently the lowest of the 31 statesthat limit residents to state exemptions. Instead, exemptions have beenenhanced for four groups of filers: Individuals age 62 or older ( 12,500) [2004]; married couples with one spouse age 62 or older ( 20,000) [2004]; married couples with both spouses age 62 or older ( 25,000)[2004]; and individuals with custody of a minor child ( 25,000) [2007],doubled by judicial ruling for joint filers [2009].These exemption amounts have remained unchanged since they wereadopted.After several efforts to increase the individual and joint homesteadexemptions over the last 20 years, the General Assembly enacted PublicChapter 326, Acts of 2015, requiring the Commission to study thehomestead exemption amounts in Tennessee and determine whether theyshould be increased to accurately reflect the cost of living. The act alsorequires the Commission to compare the various categories of homesteadexemptions in detail to those of other states. See appendix A.Although severalattempts have beenmade to updateTennessee’s homesteadexemption amounts, theyhave not been adjustedsince 1980 and arecurrently the lowest ofthe 31 states that do notallow residents to claimthe federal exemption.The set of federal exemptions is available to debtors in all states unlessthe state has passed a law saying otherwise. Initially, 37 states includingTennessee chose to limit residents to state exemptions; six of those stateshave since reversed course and now allow their residents to choose betweenthe federal and state sets of exemptions. Of the remaining 31 states, onlyeight including Tennessee have homestead exemptions that are less thanthe federal exemption, which is currently 22,975 for an individual and isdoubled to 45,950 for debtors who are filing jointly.A state’s homestead exemption is most often the largest exemption availableto debtors; in 40 states, it is larger than the combined dollar value of allWWW.TN.GOV/TACIR3

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of Livingother exemptions for which the law specifies an amount. Tennessee hasthe third lowest combined exemption value after the neighboring states ofMissouri and Alabama. Alabama tripled its homestead exemption amountfor individuals, which had been unchanged since 1980, from 5,000 to 15,000, double that amount for joint filers, in 2015 and indexed it to adjustfor inflation every three years. Alaska, California, Indiana, Michigan,Minnesota, Ohio, and South Carolina also index their exemption amountsfor inflation (see table 1 on page 23).If Tennessee’s homesteadexemption amounts forindividuals and jointfilers had kept pacewith inflation since theiradoption roughly 35years ago, they wouldnow be 18,513 and 21,907 instead of 5,000and 7,500.4If Tennessee’s homestead exemption amounts for individuals and jointfilers had kept pace with inflation since their adoption roughly 35 yearsago, they would now be 18,513 and 21,907. If the exemption for jointfilers were double the exemption for individuals, it would be 37,026. Asimpler way to bring these figures up to date and keep them up to datewould be to adopt or match the federal homestead exemption, which isadjusted for inflation every three years. If that were done, Tennessee’sexemption amounts for debtors with custody of a minor child, which arecurrently more than the federal amounts, would need to be grandfathereduntil the federal exemption amount catches up to it.WWW.TN.GOV/TACIR

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of LivingThe Homestead Exemption—Attempts toBalance the Interests of Debtors and Creditorsin Tennessee and Other StatesEvery state has laws that protect some of the assets ofdebtors from the satisfaction of claims by creditors.These “property exemption laws,” which are also called“bankruptcy exemptions,” have long and importantpolitical histories. Texas entered the union as the firststate with property exemptions—designed, it was saidat the time, to draw settlers from other states—but thesouthern states responded quickly with exemptionsof their own, and today every state has propertyexemptions, frequently quite generous. Like usury,stay, and currency laws, exemption laws have played animportant role in the perennial conflict between debtorsand creditors.The Political Economy of Property Exemption LawsEric A. Posner, Richard Hynes, and Anup Malani2With traditional consumer loans, lenders could often meet their customersface to face, and the extension of credit was a personal act based on a goodfaith guarantee of repayment. As Professor Maurie J. Cohen, writing inthe International Journal of Consumer Studies, put it, “this geographicproximity enabled lenders to rely on individual judgment to gauge thelikelihood of default and to set their rates and terms accordingly.”3 Butthe nature of personal credit began to change in the 1950s and 1960s withthe advent of credit cards, and debtor-creditor relationships that were nolonger limited by location. Tim Westrich and Malcolm Bush, researchersfocused on community reinvestment and economic development,characterized this change in a report presented at a Federal DepositInsurance Corporation conference:With traditionalconsumer loans, lenderscould meet theircustomers face to face,and the extension ofcredit was a personal actbased on a good faithguarantee of repayment.Before [the late 1960s], consumer credit was extendedby banks primarily through installment loans for largedurable goods, such as the family automobile, furniture,and large appliances. “Open-ended” credit was rare.Otherwise, consumers could obtain credit only through“open book” accounts or “tabs” with local businesses,usually guaranteed by a personal relationship betweenthe business owner and the consumer. In the late 1950s,banks began to explore alternatives to these small23Posner et al. 2001, p. 1.Cohen 2007, p. 60.WWW.TN.GOV/TACIR5

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of Livingconsumer loans, which had high overhead costs andlabor-intensive underwriting. Enter the credit card:an instant line of open-ended credit. Bank of Americalaunched the BankAmericard, the first universal creditcard, in 1958; imitators were quick to follow. By 1970,the United States was blanketed by two large merchantnetworks, the predecessors to Visa and MasterCard.4“The deregulationof consumer interestrates in the late 1970striggered a dramaticincrease in consumercredit availability,charge-off rates, andpersonal bankruptcies.”As credit cards became more widespread, banks felt constrained by stateusury laws capping interest rates. Lawrence M. Ausubel, an economistwriting in The American Bankruptcy Law Journal, said, “. . .during the 1970s,the banking industry heavily litigated the issue of the “exportation” ofinterest rates, i.e., the issue of which state’s usury ceiling constrains theinterest rate if a bank located in one state issues a credit card to a consumerin a different state.”5 This controversy worked its way up to the US SupremeCourt, and in a 1978 ruling, Marquette National Bank of Minneapolis v. FirstOmaha Service Corporation, the Court allowed consumer credit agenciesto apply the interest rates from the state in which they incorporated. Asexplained in the January/February 2007 issue of the Federal Reserve Bankof St. Louis ReviewPrior to this time, many states had usury ceilings oncredit card interest rates. The high inflation and interestrates of the late 1970s significantly reduced the earningsof credit card companies. As a result, credit cardcompanies in states with relatively high interest rateceilings attempted to solicit their credit cards to peopleliving in states with lower interest rate ceilings—and stillcharge the higher interest rates.Diane Ellis 1998. “The Effectof Consumer Interest RateDeregulation on Credit CardVolumes, Charge-Offs, andthe Personal Bankruptcy Rate.”Federal Deposit InsuranceCorporation, Bank Trends.Controversy over this practice culminated in [theMarquette case] in which the Supreme Court ruledthat lenders in states with high interest rate ceilingscould export those high rates to consumers residing instates with more restrictive interest rate ceilings. Theresult of this ruling was an expansion of credit cardavailability and a reduction in the average credit qualityof cardholders.6After the Marquette ruling, many states increased or eliminated theirusury limits in order to compete for the business of national lenders and4566Westrich and Bush 2005, p. 5.Ausubel 1997, p. 18.Garrett 2007, p.21.WWW.TN.GOV/TACIR

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of Livingallow state-chartered banks to compete more equally with national ones.7According to the same St. Louis Fed article, the expansion in credit cardsand reduction in the average credit quality of card holders were amongseveral factors contributing to a striking increase in bankruptcy filings inthe last quarter of the 20th century. The article notes two characteristicsof that period that have made individuals more susceptible to incomeshocks and thus more likely to file for bankruptcy: consumer debt serviceas a percent of income increased from about 11% of personal income in1980 to nearly 14% of income in the second quarter of 2005 and Americanshave been saving less and spending more by taking on more debt.8 Figure1 illustrates the rise in revolving consumer credit since the time of theMarquette ruling; figure 2, from the St. Louis Fed article, shows a similarrise in bankruptcies.Figure 1. Revolving Consumer Credit Outstanding in the US(Millions of dollars; not seasonally adjusted) 1,200,000 1,000,000 800,000 600,000 400,000 200,000 01970197519801985199019952000200520102015Note: Revolving credit outstanding is mostly credit card debt but also includes prearranged overdraft plan debt.Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Historical Data, Consumer Credit - G.1Figure 2. Personal Bankruptcies per Thousand Population in the US, 1900 to 02000Source: Garrett, Thomas A. 2007. "The rise in personal bankruptcies: the Eighth Federal ReserveDistrict and beyond." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 89, no. January/February 2007.Tennessee’s current usury limit is the greater of 24% or 4% above prime. Tennessee CodeAnnotated, Section 47-14-102(7).8Garrett 2007.7WWW.TN.GOV/TACIR7

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of LivingBankruptcy reform in the 1970sExemption laws also play an important role in federalbankruptcy law, and it is here that they enjoy a higherprofile. The treatment of state property exemptionsin the federal bankruptcy code of 1978 resulted froma compromise between the House, which sought toestablish a mandatory system of federal exemptions, andthe Senate, which sought to incorporate state exemptionlaws as the older bankruptcy law did.The Political Economy of Property Exemption LawsEric A. Posner, Richard Hynes, and Anup Malani9The wide disparity instate exemption lawsbefore passage of the1978 federal BankruptcyReform Act createda hodgepodge thatcreditors and bankruptcycourts found difficult toadminister.By the time of the Marquette decision, Congress had been consideringbankruptcy reform for roughly a decade. As Bret Fulkerson, AssistantAttorney General, Texas Attorney General’s Office put it, “Unlike othermajor amendments to United States bankruptcy law, the 1978 Act was notpassed in response to an economic downturn. Instead, changes were madeto the 1898 Act because it was perceived as outmoded and unresponsiveto the needs of both debtors and creditors.”10 The last major change was40 years earlier.11 The wide disparity in state exemption laws created ahodgepodge that creditors and bankruptcy courts found difficult toadminister. This hodgepodge also made navigating the bankruptcyprocess and making a fresh start difficult for debtors. In response to theseconcerns, Congress modernized the US bankruptcy code. The BankruptcyReform Act of 1978 established independent federal bankruptcy courts;12listed a set of exemptions for debtors, including a homestead exemption;and eased the process of filing for Chapter 13, which allows debtors torepay their debt without selling (liquidating) their assets. Until then,Chapter 7, which allows debtors to discharge most of their debts but mayrequire them to give up some of their property, was the only alternativeavailable to most debtors.Tennessee’s high bankruptcy ratesConsumers end up in bankruptcy court for many reasons. Medical bills,13job loss and other income reduction, or divorce-related costs are frequentlycited as reasons.14 Financing everyday expenses with credit cards asPosner et al. 2001, p. 1.Fulkerson 2002, p. 305.11The Chandler Act of 1938 first established Chapter 13.12They are adjuncts to the federal district courts, which handled bankruptcy cases before that timeand retain authority to issue final orders in bankruptcy cases. http://www.fjc.gov/history/home.nsf/page/courts special bank.html.13Himmelstein et al. 2009.14Garrett 2007.9108WWW.TN.GOV/TACIR

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of Livingdiscussed earlier, accumulating student loan debt, and taking on high-riskhome loans may also lead a consumer to bankruptcy. When consumersfall behind in paying revolving credit15 such as credit cards, debt canincrease quickly because of late fees, interest rate hikes, and over-limitfees. Citing other research, the 2007 St. Louis Fed article quoted aboveidentifies the typical person filing for bankruptcy as “a blue collar, highschool graduate who is the head of a household in the lower middleincome class, with heavy use of credit” and identifies the primary cause ofpersonal bankruptcy as “a high level of consumer debt often coupled withan unexpected insolvency event, such as the loss of a job, a major medicalexpense not covered by insurance, divorce, or death of a spouse.”16Tennessee is widely recognized as having the highest overall bankruptcyfiling rate per 1,000 residents in the country but is one of only nine states,mostly southern, in which most people filing for bankruptcy do so underChapter 13.17 See Map 1. Tennessee ranks first for Chapter 13 filings andtenth For Chapter 7 filings, and more bankruptcy filers in Tennessee useChapter 13 (59.7%) than all but three other states. Nationally, 35.8% ofbankruptcy filers use Chapter 13. See appendix B for bankruptcy filings bystate, appendix C for a comparison of federal bankruptcy Chapters 7 and13, and appendix D for a description of all federal bankruptcy chapters.Based on research reported in a 2009 article in the Journal of Law andEconomics, Tennessee’s overall high rank for bankruptcy filings may bedirectly connected to its high percentage of debtors using Chapter 13 orthe demographics of its population, including family structure, race, andeducation, but it is not likely that it has anything to do with the state’sproperty exemption amounts, largely because few bankruptcies involvesignificant assets:Tennessee is widelyrecognized as havingthe highest overallbankruptcy filing rateper 1,000 residents inthe country but is one ofonly nine states, mostlysouthern, in whichmost people filing forbankruptcy do so underChapter 13.To the extent that the legal system places little pressureon delinquent debtors, many individuals may default ontheir debts without filing for bankruptcy . . . . Indeed,comparisons of bankruptcy rates across any two statesmay be largely uninformative regarding the rate ofdefault if their policies regarding garnishment are notthe same.Another important predictor of state level bankruptcyfiling rates is the fraction of bankruptcies filed underRevolving credit allows debtors to withdraw a loan, repay it in full or in part, and redraw thebalance again and does not have a fixed number of payments.16Garrett 2007 p.17.17The nine states are, in order from highest to lowest percentage for Chapter 13 filings, Louisiana(71.5%), Alabama (64.0%), South Carolina (59.8%), Tennessee (59.7%), North Carolina (59.4%),Texas (59.3%), Georgia (56.6%), Arkansas (53.5%), and Mississippi (51.9%).15WWW.TN.GOV/TACIR9

10HICAORNVWAAZIDUTNMCOWYMTChapter 13Chapter 7NESDTXOKKSNDIAMNSource: American Bankruptcy InstituteNine states where Chapter 13filings exceed Chapter 7Bankruptcy Filings by Type: January - November 2015AKLAARMOILMSWIKY0TNMIALINMap 1. Bankruptcy Filings by Type: January – November 7505MDNHTennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of LivingWWW.TN.GOV/TACIR

Tennessee’s Homestead ExemptionsAdjusting Them to Reflect the Cost of LivingChapter 13 of the bankruptcy code. This fraction isextremely stable over time, plausibly suggesting thatit represents the legal culture of the attorneys andbankruptcy courts in the state. Chapter 13 bankruptciesrequire filers to repay a fraction of their debts. Sincedebtors are usually unable to comply with the terms oftheir repayment plan, the majority of such bankruptciesare dismissed. Debtors whose bankruptcies aredismissed often file again, increasing the total numberof bankruptcy filings. Thus legal inst

debtors are not left destitute when they fall on hard times. These laws protect both real and personal property. Real property protections are called homestead exemptions and typically protect a certain amount of equity held in an individual's primary residence but in some states protect the entire residence regardless of its value.