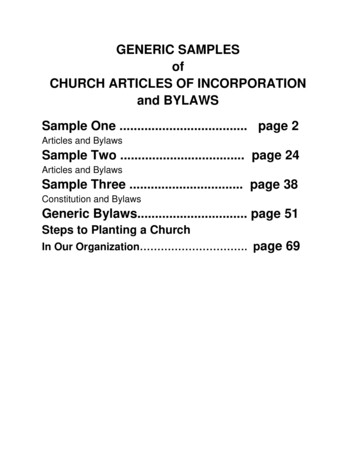

Transcription

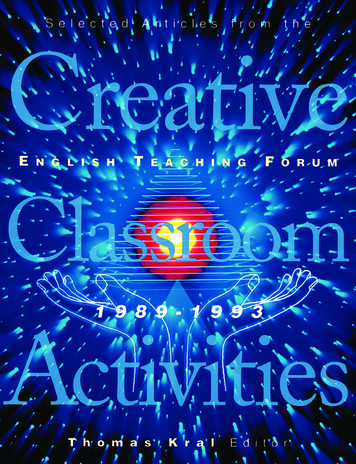

SelectedArticlesfromtheCreativeEn g l i s hTE a c h i n gFo r u mClassroom1 9 8 9 - 1 9 9 3ActivitiesT h o m a sK r a lE d i t o r

Office of English Language ProgramsUnited States Department of StateWashington, D.C. 205471995Layout and Design: Caesar JacksonFront Cover:Special Effects: Hands/Pyramid/Ballc. Orion SVC/TRDNG 1994FPG International

PREFACEThe articles that appear in the English Teaching Forum reflect a creativity and original ity that is integral to successful language teaching. Each issue of the journal witnessesthe fact that creativity cuts across all national boundaries. It is the product of the ded ication and innovative spirit of teachers worldwide.Of the 420 articles that appeared in the Forum during the five year period cov ered by this collection, 24 have been selected for their particular usefulness in makingthe classroom a focal point for creative language teaching and learning. Teachers areinvited to examine the different activities and materials presented in this volume toconsider how they may be adapted to their own teaching environment. Through thissharing of ideas and experimentation with new approaches, teachers are renewed andstudents are well served.Assisting me at various stages in the production of this anthology are the fol lowing people: William Ancker, Damon Anderson, Marguerite Hess, Caesar Jackson,Shalita Jones, Alexei Kral, Cynthia Malecki, Thomas Miller, Anne Newton, DeloresParker, George Scholz, Charles Seifert, Frank Smolinski, Betty Taska, Laura Walker,James Ward, Lisa Washburn, and George Wilcox. I thank them all for their support.T h o m a s K r a l

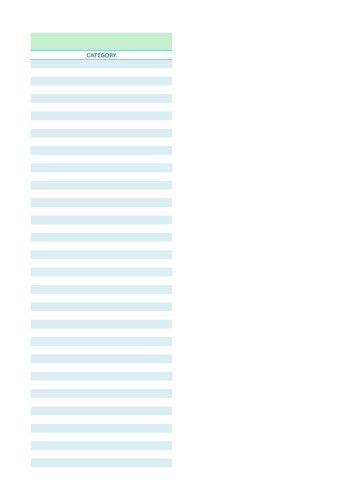

CONTENTSS ECTI O N O N E : ACTIVATING COMMUNICATION1.Structuring Student Interaction to Promote Learning . 2Lise Marie Ilola, Kikuyo Matsumoto Power, and George Jacobs2.Let Them Do Our Job! Towards Autonomy via Peer-Teachingand Task-Based Exercises . 9Claude Sionis3.The Personal Interview: A Dynamic Teaching Device .16Myo Kyaw Myint4.Why Don’t Teachers Learn What Learners Learn?Taking the Guesswork Out with Action Logging .19Tim Murphey5.“Active Listening”: An Effective Strategy in Language Learning .25Rut h Wa j n ry b6.Dictation: An Old Exercise—A New Methodology .28Mario Rinvolucri7.Why is Dictation So Frightening .32Kimberlee A. ManziS ECTI O N T W O : MATERIALS DEVELOPMENT8.Linking the Classroom to the World: The Environment and EFL .37Susan Stempleski9.The Use of Local Contexts in the Design of EST Materials .49Robert J. Baumgardner and Audrey E. H. Kennedy10.A Cognitive Approach to Content-Based Instruction .54Daniela Sorani and Anna Rita Tamponi11.Films and Videotapes in the Content-Based ESL/EFL Classroom .62Fredricka L. Stoller12.Problem-Solving Activities for Science and Technology Students .70Alain Souillard and Anthony Kerr

13.A Gallery of Language Activities: U.S. Art for the EFL Class .77Shirley Eaton and Karen Jogan14.Using Board Games in Large Classes .85Hyacinth Gaudart15.Putting Up a Reading Board and Cutting Down the Boredom .91Keith Maurice, Kanittha Vanikiet and Sonthida Keyuravong16.Gearing Language Teaching to the Requirements of Industry .97Paola C. FalterS ECTI O N T H R E E : ACTIVITIES FOR TEACHING READING17.Purpose and Strategy: Teaching Extensive Reading Skills . 104Ken Hyland18.Teaching Reading Vocabulary: From Theory to Practice . 110Khairi Izwan Abdullah19.ESP Reading: Some Implications for the Design of Materials . 117Salwa Abdul GhaniS ECTI O N F O U R : ACTIVITIES FOR TEACHING WRITING20.A Balanced Approach to the Teaching of Intermediate-LevelWriting Skills to EFL Students . 122Paul Hobelman and Arunee Wiriyachitra21.Some Prewriting Techniques for Student Writers . 127Adewumi Oluwadiya22.Using Student Errors for Teaching . 134Johanna KlassenS ECTI O N F I V E : ACTIVITIES FOR TEACHING LITERATURE23.The Double Role of Fiction in Foreign-Language Learning . 143Elisabeth B. Ibsen24.Developing Materials for the Study of Literature . 154Susanne Bock

1SECTIONA C T I VA T I N GCOMMUNICATIONGroup learning and performance depends onboth individual accountability and groupinterdependence; for anyone in the group tosucceed, everyone in the group must succeed.Lisa Ilola, Kikuyo Power, and George Jacobs

1Structuring StudentInteractiontoPromote LearningL I S A M A R I E I L O L A , K I K U YO M AT S U M O T O P O W E R , A N D G E O R G E J A C O B SUniversity of Hawaii USAA classroom may not have a computer , teacheraides, or the latest in sophisti cated materials, but everyclassroom has students. Harnessing this abun dant nat ural resource has been the sub ject of a surge ofresearch and curricular materials beginning in theearly 1970s. These pedagogical approaches are knownby a variety of names: “coopera tive,” “collaborative,”“peer-inter active,” and “peer-tutoring” approach es.While there are differences in the meanings of theseterms, the commonality is that they all refer to ways tomaximize student learning through student-studentrather than direct teacher-student interaction. In thisarti cle “cooperative learning” and “peer- interactivelearning” are used as gener al terms referring to thesetypes of teaching methods.There are many reasons why it is ad vantageous for ateacher to use these methods. Compared to the tradi tional lecture approach, peer-interactive ap proacheshave fared well. In addition to higher levels of academ ic achieve ment, an increase in self-esteem, attendance,and a liking for school have been reported in a numberof reviews of research on peer-interactive methods(Aronson and Osherow 1980; Slavin 1980; Sharan1980; Johnson 1981). An increase in mutual concernamong students and the development of positive peerrelationships have also been reported. This was alsoobserved in class rooms that contained racially and cul turally different, socially isolated, and handicappedstudents (Slavin 1985; Lew et al. 1986; Slavin 1987).Merely putting students in groups isn’t enough.Student interaction needs to be structured to matchinstructional goals. In the ESL/EFL classroom, devel oping proficiency in reading, writing, listening, andspeaking the target lan guage, as well as acquiring knowl edge of culture, are core instructional goals. Studentinteraction also needs to be structured so that the manybenefits of peer-interactive approaches can come about.Structuring harmonious interactionThe acronym ARIAS stands for five important“notes” that can be used to compose different types ofstudent in teraction. Just as the harmony of musicalarias is built through the proper re lation between dif ferent notes, so, with knowledge of the proper “notes,”a teacher can successfully orchestrate classroom inter action. The issues of Accountability, Rewards, Interdepen dence, Assignments, and Social Skills (ARIAS) willbe discussed next.In order for peer-interactive sessions to be success ful, students must make worthwhile individual contri butions as well as benefit from contributions made byothers. Group learning and perfor mance depends onboth individual ac countability and group interdependence; group members sink or swim together—i.e., foranyone in the group to succeed, everyone in the groupmust succeed.Both individual accountability and interdependenceamong students can be structured through rewards(indivi dual/team/class). Winning a contest based ongroup competition is one type of reward. A group canalso be reward ed without competition. Here, studentswork in groups to create a group prod uct, and allreceive the same reward: a grade or other feedback.One group’s “win” is not another group’s “loss”; eachgroup can get an A. Or rewards may be a combinationof an individual’s and the team’s score (the sum of thequiz scores for all team members; for details and varia tions, see Kagan 1988). In all of these examples, theteam re ward is designed to promote interde pendenceamong team members.

Continually working in the same teams may notcontribute to a feeling of overall interdependenceamong all stu dents in the class. In order to promotethe development of a positive overall class spirit, teamscan be re-formed throughout the year and classrewards can be occasionally awarded. Here, the teamswork together to earn a reward that is shared by theentire class (Kagan 1988). For example, if 90% of thestudents score above 80 on a vocabulary quiz, the classgets to listen and sing along to pop songs on a taperecorder at the next class meeting.Individual accountability and group interdepen dence can also be structured by the assignment.Completing an as s ignment requires that studentsengage in certain behaviors and complete vari ous sub tasks. For example, if three students work together as agroup on a composition about changes they would liketo see in their school, each person can have the task ofwriting about one change. Then they would come backto gether to write an introduction and conclusion, aswell as revise each per son’s section and ensure that theentire composition flows smoothly.Role-based peer interactionStudent interaction can also be struc tured by assigning students specific behaviors or roles. When first intro ducing this to the class, it is helpful to give each student acopy of a description of the responsibility of each role.For example, Jacobs and Zhang (1989) placed EFLwriting students in groups of three for peer feedbacksessions. Students gave each other feedback on theircompositions according to the demands of their roleas either Writer of the compo sition, Commenter onthe composition, or Observer of the interaction.Another way that assignments can be used to struc ture interaction in volves practicing reading, speaking,and listening. Here, students can be as signed to groupsof three and instruct ed to cooperate with each otherby en g aging in one of three roles: Summarizer,Elaborator, or Facilitator—roles that represent cogni APPENDIX 1The Southern GentlemanTamako is a young Japanese woman who lived in Tokyo. In September, she went toMiami, Florida, to study at a university there. Tamako’s uncle lived in Miami, so Tamakostayed at his house. When she came to Miami, Tamako began a special program to introduce new students to the university. There was a young man named Jack, from the southern state of Alabama, who was also in the group of new students with Tamako.As the new students walked together around the university, Tamako noticed that whenJack was near her, he helped her in many ways. For example, he always opened doors forher. Also, when Tamako asked Jack a question, he always smiled and answered the question kindly. Jack even took Tamako’s arm to show her where to go, when the studentscrossed a street. Tamako enjoyed all this attention very much and stayed near Jack all dayso that she could ask him more questions and he could do more things to help her.That evening Tamako was very excited. When she came back to her uncle’s house, shetold her cousin that she now had an American boyfriend. Her cousin was very surprised.Her cousin did not un derstand how Tamako could already have a boyfriend after onlytwo weeks in the United States.

APPENDIX 2Which answer do you think best ex plains what is going on in The Southern Gentleman?1.2.3.4.5.Jack visited Tamako in Tokyo last summer. That is why Tamako came to the U.S., butTamako never told anyone.Jack is a typical playboy-type col lege man and is trying to use Tamako.Tamako misunderstands what Jack did.The pace of life in the U.S. is very fast. It is not unusual for people to find boy friendsand girlfriends very quickly.In Japan Tamako’s parents did not al low her to have a boyfriend. She came to theU.S. to have more freedom. Tamako is showing her freedom by having a boy friend.APPENDIX 3Rat iona le s for Alter nat ive An swers1.2.3.4.5.You chose 1. This is very unlikely, be cause the story says that Tamako met Jack in theintroduction program. Please make another selection.You chose 2. Some U.S. men are playboys, but that is not true of all Ameri can men. Inthe Southern states of the U.S., in particular, men are taught to open doors for women,help them cross the street, and so on. Perhaps he wants to be Tamako’s boyfriend, butwe do not know because Jack’s actions were normal, po lite actions for a young manfrom the South. Please choose again.You chose 3. Tamako has been in the U.S. only two weeks. In Japan, it is not usu al formen and women to talk and touch on the first day they meet each other. Howev er,this is natural for Jack. Tamako does not understand this. People from other countriesoften misunderstand the customs of the country they are visiting. This is the bestanswer.You chose 4. Yes, life in the U.S. moves quickly; but life in Tokyo moves quickly also.Although in the U.S. people probably do find boyfriends or girl

oping proficiency in reading, writing, listening, and speaking the target language, as well as acquiring knowl edge of culture, are core instructional goals. Student interaction also needs to be structured so that the many benefits of peer interactive approaches can come about. Structuring harmonious interaction