Transcription

mediterraneanclimatelandscapesJennifer Natali, Matt Kondolf, Clara Landeiro, Juliet Christian-Smith, Ted GranthamA LIVINGMEDITERRANEANRIVERRestoration and Management of the Rio Real in Portugalto achieve Good Ecological Condition

published byThe Department of Landscape Architecture & Environmental Planningand the Portuguese Studies Programof the University of California, BerkeleyInstitute of Urban and Regional Development Working Paper WP-2009-01University of California Water Resources Center Contribution Number 209Institute of European Studies Working PaperISBN-13:978-0-9788896-3-0; ISBN-10: 0-9788896-3-0february 2009View over Bombarral to the Rio RealThe course at University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley), Mediterranean-ClimateLandscapes (International and Area Studies 229 and Landscape Architecture 229) involvescomparative study of natural processes, planning, policy and legislation in Mediterraneanclimate regions. Graduate students conduct original research, develop plans and designs toenhance environmental and social conditions by working collaboratively with faculty andstudents from Portuguese universities.In Spring 2007, the course focused on the European Water Framework Directive (WFD) and itsimplementation in Mediterranean climates. At the international workshop held in Bombarral,Portugal (May 25 to June 1, 2007) students from UC Berkeley and the Universidade Técnicade Lisboa (UTL) investigated how implementation of the EU Water Framework Directivemight impact the local community of Bombarral in the Rio Real Basin, northwest of Lisbon.The international team of students worked with local officials and land owners to developrestoration strategies that would address the priorities of the community and the stipulationsof the WFD. This work is very relevant to the current process of WFD implementation.This report and the research upon which it was based were supported by grants from theLuso-American Foundation (Lisbon, Portugal), the Pinto-Fialon Fund (administered by thePortuguese Studies Program) and the Beatrix Ferrand Fund of the Department of LandscapeArchitecture and Environmental Planning, both at the University of California, Berkeley.Further information on the Portuguese Studies Program at UC Berkeley is available online at:http://ies.berkeley.edu/psp/portuguesestudies/

EDITORSJennifer Natali, Matt Kondolf, Clara Landeiro, Juliet Christian-Smith, Ted GranthamA LIVINGMEDITERRANEANRIVERRestoration and Management of the Rio Real in Portugalto achieve Good Ecological ConditionTABLE OF CONTENTSMediterranean Climate Drainage Basin Management4European Union’s Water Framework Directive6the Rio Real Basin8Flood ManagementArturo Ribeiro, Julian Fulton, Laura Norlander, Patricia Terceiro12Agricultural Impacts Management StrategiesAndre Chan, Lyndsey Fransen, Timothy Minezaki, Carla Santos20Risks of the Giant ReedArielle Simmons, Eike Flebbe, Cecilia Simões, Melissa Parker26Climate Appropriate Urban Water ManagementRebecca Leonardson, Brooke Ray Smith, Rui Teles32Urban Waterfront RegenerationCristina Santos, Maria Matos Silva, Nadine Soubotin, Theresa Zaro38Conclusion Acknowledgements44

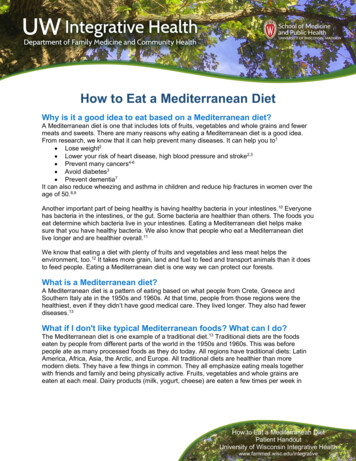

Climate influences our use of the land and its resourcesA LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER4In Mediterranean climates, mild year-roundtemperatures support comfortable humansettlement with rich agricultural regions.The climate’s long summer drought,seasonal river flow, high inter-annualvariability in precipitation, and episodicfloods threaten these settlements, leadingto highly manipulated hydrologic systems.The degree of hydrological alteration andconsequent ecological change is typicallymuch greater in Mediterranean-climaterivers than humid-climate systems. Dams,diversions, irrigation channels, storageand distribution facilities simultaneouslyrestrict flow regimes, support economicdevelopment and destroy the nativebiological communities in Mediterraneandrainage basins. Overcoming the complexrelationships among climate, economyand our entangled legal and politicalinstitutions challenge the restorationpotential of Mediterranean-climate riversystems worldwide.CALIFORNIA AND PORTUGALIn California, native fish species continueto decline in highly-altered river systemsthat strain to supply water to a growinghuman population. In Portugal, 40% ofthe 1,853 water bodies are classified as “atrisk,” including surface waters of the RioReal basin, while another 20% of waterbodies have insufficient data to be assessedat present.1 The extent and sources ofecological deterioration remain elusiveas scientists and policy-makers struggle1Commission of European Communities 2007

“Water is not a commercial product like any other but rather aheritage which must be protected, defended and treated as such.”--Directive 2000/60/EC of the EU Parliament and Councilto develop methods and plans withoutunderstanding pressures and impacts,baselines, and relationships between landuse and water quality.Water quality goals are often framedas chemical issues to be resolved withwastewater treatment plants and reductionin non-point source pollution. The widerscope of ecological impacts caused byhydro-morphological alterations, however,rise to the forefront as major obstacles forMediterranean-climate river restorationefforts due to the important economicservices provided by water infrastructure.Typically, high-maintenance levees for floodprotection, dams for water storage andhydropower, and diversions for agricultureirrigation are managed by multipleoverlapping agencies with conflictingmandates.While the European Water FrameworkDirective (WFD) promises a basin-scaleinstitutional structure with the scopeand authority to develop and regulatecatchment management plans, the longstanding local needs for flood defense,water treatment and water supplyinfrastructure will be implemented bymunicipalities, land owners and farmerson the ground. Collaboration amongresearchers in other Mediterranean-climateregions holds promise for identifying abroad range of solutions.department of landscape architecture and environmental planningMEDITERRANEAN-CLIMATE DRAINAGE BASIN MANAGEMENT5

source: Grantham 2008A LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER6According the River BasinCharacterization reportscarried out in 2004,water uses with the mostsignificant negative impacton water status includeagriculture,navigation,power generation andurbandevelopment.Urban dwellers pay mostof the financial costs ofwater supply and wastetreatment.Photo: A new wastewatertreatment plant in the RioReal basin addresses manywater quality concernsin the basin, but doesnot address industrial,agricultural and ruralwater treatment nor theoverall ecological healthof the drainage basin.The European Parliament and Council'sadoption of the Water Framework Directive(WFD) in 2000, requires its 27 memberstates to make substantial progresstowards improving the ecological, chemicaland quantitative status of rivers, lakes,groundwater and coast waters by specificdeadlines.1 The framework emerged out ofan on-going dialogue over the ecologicalrestoration of substantially modifiedEuropean water bodies. It establishes acoherent and comprehensive decisionmaking process for managing waterresources by defining a sequenced, iterativeapproach to achieving 'good ecologicalstatus' for all water bodies. The first stepbegan with a baseline characterizationfor each river basin that was completed in2004. Authorities then analyze pressuresand impacts in order to plan, legislate andimplement effective management practicesand improvements as they strive to achievebasin-specific goals by 2015. Every sixyears, the steps are repeated in an adaptivemanagement cycle.In implementing the framework, eachriver basin unit defines its own uniqueinstitutional authority that unites upstreamand downstream interests and crossespolitical boundaries in order to opencommunication between local, regional,and national institutions as well as nongovernmental stakeholders. As riverscross international and political borders,so do management plans, requiringunprecedented levels of cooperation.Transparency in decision-making,documentation and participation areexplicit requirements. Each basin mustimplement the classification process, setenvironmental objectives, coordinatemanagement activities and executeregulatory action to achieve objectives.

The framework recognizes the economy’sinfluence on human behavior. In additionto creating plans and implementing policy,each river basin authority must developits own water pricing system. The basinauthority must take stock of its uniquesupply and demand conditions along withlocal environmental, economic and socialpriorities. While the framework does notdefine prices across the EU, it defines acommon pricing process. The accountingfor who uses, pollutes, pays and subsidizeswater within each basin will be analyzed,shared, debated and redefined in an openforum. This applied principle of costrecovery requires that users of water makean adequate contribution to the financialand environmental costs of the waterservices, from supply infrastructure towaste treatment.The WFD aims to recognize the diversityof its member states by allowing flexibleresponses to complex water managementchallenges faced by diverse cultures andclimates. Ultimately, the WFD may helpsocieties adapt to future environmentalchallenges, such as the impacts of climatechange, by increasing the resilience ofecosystems and reducing the impacts offloods and water scarcity.EU-wide, approximately 40% of surfacewaters are classified as "at risk" of notachieving good status by 2015. 2 Theleading pressures on these water bodiesis hydromorphological alteration -changes in the natural hydrology (flowregime) and morphology (e.g. channelform, connectivity) resulting from waterdiversions and extraction, as well as flooddefense and water supply infrastructureserving agriculture, navigation, hydropowerand urban development.31 Scheuer 2005. EU environmental Policy Handbook published by the European Environmental Bureau2, 3 Commission of European Communities 2007department of landscape architecture and environmental planningEU WATER FRAMEWORK DIRECTIVE7

PORTUGALIN EUPOPERIO REAL BASIN INRIBEIRAS DO OESTEA LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER8RIBEIRAS DO OESTEREGION IN PORTUGALWith nearly 13,000 inhabitants, the townof Bombarral sits in the center of the RioReal river basin. Its valleys are lined withvineyards and pear orchards which supporta long-standing tradition of fruit and wineproduction. In the uplands, a monocultureof eucalyptus plantations dominatesforested areas while turbines draw energyfrom the region’s wind resources. Small,clustered urban areas, such as Bombarral,support service economies and lightindustrial operations. Agriculture andforestry dominate land use, but compriseonly 10% of the basin’s economy. Servicesand construction employ much of theregion’s population.

How will the WFD affect ariver and the people wholive within its catchment?BOMBARRAL IN THERIO REAL BASINBasin area: 388 km2RIVER LENGTH: 33.8 kmPRECIPTATION: 600-800 mm/yrRIVER FLOW RATE: 189.4 mm/yrSURFACE WATER QUALITY (1998):“Extremely Polluted”100 km northwest of Lisbon via thenew A8 highway, Bombarral faces thepromise of expansion while it witnesses asteady decline in population. Bombarraland Cadaval planned for more urbangrowth in the 1990s, but the populationactually decreased. As youth migrate tometropolitan areas, vacant propertiesleave holes in the urban fabric. Touristaccommodations, housing for Lisboncommuters and second-home ownerscould draw significant development andinvestment to the area in the next ten years.Currently, the small towns and agriculturalinvestments within the basin strugglewith winter flooding and degraded waterquality. Bombarral is connected to watersupply and sewer systems, but only14% of the population is connected to awastewater treatment plant (source: INE2003). Industrial wastewater treatmentis insufficient or non-existent. Althoughthe region enjoys water surpluses today,climate change and population growthmay put pressure on existing wells andreservoirs.department of landscape architecture and environmental planningwater framework directive in BOMBARRAL9

A LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER10floods,

agriculture, invasives, stormwater, waterfrontsdepartment of landscape architecture and environmental planningThe multi-national group of students arrivedat the Hotel Comendador in Bombarral andtransformed the entire fifth floor ball roominto a research and development lab asthey applied learnings, debated approachesand designed solutions to critical issuesfacing the basin. How does the dominantagricultural land use affect the health of theRio Real and how will WFD implementationaffect farmers? How can land owners protectthemselves from floods without interruptingthe dynamic flow patterns which support lifein the river? Does Arundo donax, a pervasiveand invasive plant, affect the river’s ecologicalstatus and does anyone care? How can themunicipality minimize non-point sourcepollution from urban stormwater whileopening up urban life to its supporting river?11

arturo ribeiro, julian fulton, laura norlander, patricia terceiroRight: Aerial view of Bombarral showing floodplain of converging rivers in blue. Below: Scenes fromNovember 2006 flooding of Bombarral. Over 850 hectares of land were submerged for at least two days.source: Bombarral flood reportA LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER12How can flood management protect human interestswhile promoting good ecological status for the river?During the peak winter rain period, the cityof Bombarral often experiences flash floodevents as runoff from the upper catchmentcombines with flows the Real, Bogota, andCorga tributaries.Once the river rises over the levees andenters its natural floodplain, the waterbecomes trapped by the levees, unable todrain back into the channel. The standingwater, sitting in a bathtub of levees, cancause significant damage to crops and farmproductivity.In November 2006, the city of Bombarralexperienced a significant flood with anestimated return period of 15 years, basedon discussions with local residents.1 Sincethe flood occurred after the pear and grapeharvest, agricultural production was notsignificantly affected. Farmers did incurexpenses for damaged levees on theirproperty. The cost to rebuild the levees isestimated at 200 per linear meter.2Flooding poses serious risks to farmers,especially during the peak growingperiod from March to April. If the floodhad occurred during the growing seasonin March or April, lost revenue from cropdamage and stalled production in the basincould have ranged from 600,000 to 7million.31 Carta de Zonas Inundáveis, Município de Bombarral,February 2007.2 Personal interview with César Silvas, May 28, 2007.3 Estimates from Anteprojecto, Regularização Fluvial, Hidroprojecto, Rev 2 – 2005 – 12 – 07 assuming standing waterpersists for 2-3 days.

Rio RealRio bogata13flood management in the rio real basindepartment of landscape architecture and environmental planningRio corga

Basin CharacteristicsWe identified three major reaches of the RioReal watershed, which begins at Serra deMontejunto and ends flowing through theLagoa de Óbidos, and eventually the AtlanticOcean.Lower catchmentThe lower catchment includes a broadfloodplain that experiences frequentfloods. The Direcção-Geral de Agriculturae Desenvolvimento Rural (DGADR) hasproposed an irrigation project for the lowerwatershed to bring 1300 m³ of water from anexisting dam on the Rio Arnóia.5 The channelof the Rio Real would be widened to conveyfloods with a 2-year return period.A LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER14Middle catchmentThe middle catchment includes theflatlands of the municipality of Bombarral.Pear orchards and vineyards dominate thefloodplain. High, narrow levees have beenconstructed along the river to protect thecity and surrounding agricultural lands frominundation.Upper catchmentThe highest part of the catchment ischaracterized by narrow channels thateffectively convey water downstreamwith few flooding problems. Levees havegenerally not been constructed in this areaand therefore what flooding does occurprovides valuable storage space for watersthat would otherwise flow downstreamto more flood-prone areas.6 Much of theriparian corridor is in agriculture so soilerosion, sediment delivery to the channeland deposition in reaches may increasedownstream risk there.5 Personal interview with Isabel Loureiro, DGADR, Irrigationplan for the Po Valley, May 29, 2007.6 Personal interviews with Ricardo Noronha, Adega Cooperativa de Cataval; Nelson Isidoro, Cooperativa Agrícola doaFruticultores do Cadaval; Ana Pintéus and João Alves, CâmaraMunicipal do Cadaval, May 29, 2007.

Period of High Crop RiskRAINFALL AT VERMELHA (mm)120rainfall dataRainfall data collected from the onlyexisting gauge in the basin at Vermelhaconfirms a typical Mediterranean climaterainfall pattern. Rainfall in the basintypically peaks in December, declines aswinter concludes and spring arrives, andrises again in late March and early April.4Flood events during this second peakdisrupt the growing season and could beespecially damaging for OCTSEP04 Average monthly rainfall from gauge in Vermelhal from 1980 to 2005. Available at: http://snirh.pt/Lower catchment15BombarralCadavalupper catchmentVilardepartment of landscape architecture and environmental planningmiddle catchment

source: Bombarral residentsA LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER16levees can and will fail. the floods of december 2003 washed out thislevee, leaving orchards trapped in a bathtub of water.disadvantages of existing Flood Control StructuresIn addition to capital and maintenance costs of levees, disadvantages of highly-engineered,constricting and intensive flood control structures include:ISSUEFalse sense ofsecurityexplanationLevees can and will fail, often during the most dangerous anddamaging floods. Nevertheless, the presence of levees oftenencourages development and crop cultivation in the floodplain,putting buildings, crops, and people at risk.CROP DAMAGEFROM BathtubEffectLevees can trap and store water on farmland. Although agriculturein the Rio Real basin is able to withstand limited periods of standingwater, levees can prolong inundation periods and cause lostproductivity and significant crop damage.Increasederosion andsediment scourDisruptedsedimenttransportDegradedwildlife habitatConfining river flows to a channel will increase channel scouring,causing the bed to incise. This can lower the floodplain water table andundermine bridges and other structures.Levees eliminate the natural function of rivers to transport and spreadsediment and nutrients throughout the floodplain.Plants and animals dependant on a riparian corridor are limited to asimplified, narrow strip of vegetation within the levee system.

Restore natural functions whileprotecting sensitive infrastructurean integrated flood management strategy opens most of the floodplainas a natural sponge to store and slowly release waters after peak flows.Engineered flood protection structures will continue to play an important role in floodmanagement policies, but they should not be the only solution. A variety of integratedstrategies, applied appropriately, can reduce vulnerability while restoring a river’s potentialfor ‘good ecological status.’ Opening a river to its floodplains offers several ecologicalbenefits in addition to increased certainty and safety associated with slower, morepredictable flood velocities. These benefits include:BENEFITHABITAT ANDBIODIVERSITYWater ntionIncreasedflexibilityEXPLANATIONAllows a river to naturally move within its floodplain towards a morenatural flow pattern, thereby creating a more complex and richerhabitat for plants and animals, as well as re-creating biological cuestriggered by natural flow changes.Floodplains act as a natural filter by absorbing nutrients in the water.Slowing and storing flood waters allows infiltration and recharge ofunderground aquifers, an important water source in the Rio Real basin.Floodplain vegetation anchors river banks and filters sediment fromupland runoff before entering the stream channel.Allowing channel expanse and mobility enables communities to adaptto less predictable, more intense and frequent flood events from achanging climate.department of landscape architecture and environmental planningBenefits of integrated Flood Management17

EDUCATIONActionRemove selected levees, unless a levee isprotecting existing infrastructure directlyadjacent to the river bank that cannot beremoved or relocated. Removing leveeswill allow flood flows to diffuse over thefloodplain, drop sediment, and drainmore rapidly than if confined. In general,inundation of the floodplain will not damagevineyards or orchards as long as the floodoccurs early in the year and the water freelydrains back into the channel.Setback levees. Levees constructed directlyalong the channel restrict the ability of riversto enlarge during heavy rain events, therebyraising water levels and increasing the riskthat levees will be overtopped. Wider ripariancorridors create more flexibility for rivers toincrease in volume and meander within theirchannels, which reduces the risk that they willoverpass their levees.Reinforce existing levees with nativevegetation. In areas where levees mustremain, native vegetation should be plantedto increase stability and add habitat value.A LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER18Emphasize benefits of integrated floodmanagement. New flood managementapproaches will not succeed if farmersdo not understand the benefits providedby levee setbacks, breaches, and theconservation of native riparian corridorvegetation. River basin managersshould not assume farmers will acceptflood management strategies based onecological benefits alone. Economicanalyses explaining the increased damagethat could occur on growers fields arenecessary lessons for encouraging change inagricultural practices.Encourage stormwater retention anddetention with Best ManagementPractices. Municipalities and river basinmanagers should encourage landownersto catch water in cisterns as well as createinfiltration areas by installing green roofsand conserving permeable areas ontheir land. Published best managementpractices provide insight into the benefits,applicability and implementation.recommendations for integrated flood managementPotential fundingConclusionEuropean Union funding should befunneled through the municipalities or theOeste territory.Integrated flood management strategiesprovide effective means to achieve jointobjectives of ‘good ecological status’ underthe WFD and effective flood managementunder the Flood Directive. Global climatechange will increase the frequency andintensity of floods and provide additionalincentives to adopt flexible and dynamicflood management policies. Thesenew approaches can serve human andecological river needs as well as mitigatehuman activities that increase andexacerbate the risk of flood damage.European Agricultural Fund for RuralDevelopment: This fund comes from thecommon agricultural account allocated toeach EU member-state. Though most of thismoney typically goes to direct subsidizationof agricultural production, Portugal hasthe authority to direct these funds towardscompensation to farmers and infrastructureprojects.EU Structural and Cohesion Funds (QREN):These funds are distributed to regionsof the country based on economicdevelopment needs. The Ribeiras do Oestebasin of Portugal is considered part of theNorte hydrographic region, which recentlyseparated from the Lisbon region and isnow eligible for more funds.

PlanningIdentify, analyze and mitigateflood risks in Urban Plans Currently,Plano Director Municipals (PDMs)do not analyze how proposed urbangrowth or land re-zoning policies willaffect local and downstream floodingpotential.Increase rainfall retention anddetention areas. Urban plannersshould work with river basin managersto identify areas within cities, townsand agricultural fields for use as small,distributed stormwater storage andinfiltration areas.Enforce no-development zonesin the floodplain. Areas withinthe Reserva Ecológica Nacionallocated in the floodplain should beclearly marked as no-build zones onflood maps and in urban planningdocuments.Create no-net-increase stormwaterrunoff policies. Proposeddevelopment projects, includingnew roads, should be required toadopt stormwater runoff plans beforeobtaining development permits.Develop flood warning, response,and reconstruction plans. Developreconstruction plans before flooddamage occurs to avoid hasty actionsthat could be incompatible with longterm flood management goals.Implement data monitoring stations.Stream gauges, water quality monitorsand other indicators of physical andecological status must be installed togain a better understanding of currentriver health and function.REINFORCE WESTERNLEVEE ALONG CITYSET LEVEE BACK TOENLARGE FLOODPLAINNEW BRIDGE ATFLOOD BOTTLENECKCREATE FLOODPLAINAND URBAN PARK: 1000m2NEW COMBINEDRAILROAD TRESTLESBREACHEASTERN LEVEERioalRioRedepartment of landscape architecture and environmental planningaatgbo19Rio Real in bombarral

andre chan, lindsey fransen, timothy minezaki, carla santosAgriculture covers approximately 23,000 hectares of land in the Rio Real Basin. Of that, about 10,700hectares are planted with orchards, vineyards and olives. Polycultures, including vegetables and annualcrops comprise 10,200 hectares. Other agricultural activities include pig farms, greenhouses, and productionof vine rootstock. Agroforestry including vast expanses of eucalyptus monoculture, as well as the traditionalharvesting of cork oak in mixed forests is practiced on approximately 400 hectares in the basin.Industrial 1%Water Bodies 1%Greenhouses 1%Other Agriculture culture24%54%Orchards,Vineyards, OlivesPolyculture48%43%Urban9%LAND USE IN RIO REAL BASINA LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER20AGRICULTURAL LAND USEhow can agricultural planning and farming practicesbe adapted to protect water quality and quantity?Local perceptions of water quality issuesoften focus on urban sewage. Land usemanagement plans and experts, however,identify sedimentation and pollution fromagri-chemicals and pig farms as a sourceof serious water quality problems in thewatershed.In Mediterranean climates where prolongeddry periods are expected, water quantityis another significant concern, yet localregulations and policy have largely ignoredthe issue.For decades, groundwater supplies havebeen sufficient to irrigate Rio Real orchardsand crops. Threats to this supply encroachfrom each end of the catchment. Near thecoast, groundwater mining will lead tosaltwater intrusion, rendering the aquiferunsuitable for irrigation. In the headwaters,a sanitary landfill threatens neighboringgroundwater sources with each intenserainfall event. Moreover, a breach inthe lining of the landfill could result incatastrophic pollution of the entire aquifer.Contamination is not the only issue. At thecurrent rate of groundwater extraction,the aquifer appears insufficient for futureneeds. Above-ground water sources alsoprove unpredictable, despite appearancesof plenty. Only the artificial inputs fromsewer outfalls keep river beds wet duringsummer months.The effects of climate change mustalso influence water resource planning.Introducing economic incentives toconserve water use as well as encouragebetter flood management will be of majorimportance in maintaining the social andeconomic viability of the region.

Agriculture dominates the landscapeof the Rio Real basin. Across acatchment, extensive agriculturecan negatively impacts water bodiesby increasing salinity, reducingenvironmental flows, introducingpesticides, and increasing nutrientsand turbidity.agricultural impacts management strategies21department of landscape architecture and environmental planning

Erosive potential of steepslopes in the hills of theRio Real watershed.Cross section showscontaminant sourcesand flows. Residualcontaminants insoil pores leach intogroudwater and flowtowards streams.SEWERPIPESLANDFILLROADSSEPTICSYSTEMCROPS ONSTEEP SLOPESPIG FARMSPESTICIDES NUTRIENTSLANDSURFACEWATER TABLEHOUSEHOLDWELLA LIVING MEDITERRANEAN RIVER22STREAMIRRIGATIONWELLGROUNDWATER“A 2ha forest along stream setbacksinofthebasin andcouldsequestertons ofSourcesSurfaceGroundWater6Contaminationcarbon, help stop global warming, and earn farmers 9,000 euros annually.”Stream setbacks & riparian buffersA stream setback prohibits developmentor disturbance within a certain distancefrom the river in order to reduce erosion ofthe banks and establish a valuable riparianbuffer. Swaths of native riparian vegetationnot only stabilize the banks, but can alsolower water temperature by shading theriver, creating habitat for aquatic andriparian organisms and providing a bio-filterfor stormwater runoff.Stream setbacks can also decrease cropdamage during floods. By removing leveesto create a riparian buffer, propertiesbetween the levee and channel willexperience more frequent floods, but overthe long term, the risk of flood damagedecreases as the buffer provides faster,more effective drainage for flood waters torecede. Most of the crops grown in the RioReal watershed can withstand flooding, aslong as the water only remains for one tothree days. The ‘bathtub effect’ created bylevees trapping water in agriculture fieldscreates extensive and costly crop damage.Trapped floodwaters generate high cleanup costs for farmers, ranging from waterpumping to sediment removal.Currently, Portugal’s Dereito-Lei 46/94states that all land within 10-meters of ariver is part of Portugal’s ‘public domain’and is automatically required to functionas a riparian setb

5 de P a R t M ent of landsca P e a R chitectu R e and envi R on M ental P lanning "Wat e r is n o t a c o m m e r cai l p ro d u c t lki e a n y o t h e r b u t rather a h e rti a g e W hc i h m u s t be protected, defended a n d treated a s s u c h."--directive 2000/60/ec of the eu Parliament and council