Transcription

Berkeley Economic Review presentsIssue 6IN THIS ISSUE“Water Finds the Leak” A World Without Coffee The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Produce Movement More

STAFFEditors-in-ChiefSarah BuiVatsal BajajYutao HeZhiming FengCharles McMurryParmita DasEditorsStaff WritersAmanda Yao*Andy Babson*Abhishek RoyAlly MintzerAmanda ZhangCourtney FungDivya VemulapalliKaley KranichKareena HargunaniKat XieLucia DardisMarley OttmanMillie KhoslaPallavi MurthyRaina ZhaoRaksha SenSean O’ConnellSebastian Andrew MarshallAlly KennedyAni BanerjeeChazel HakimDavis KedroskyEkaterina YudinaJaide LinJennifer Mei JacksonNajati NabulsiNicolas DussauxOlivia Diane DoironRia BhandarkarSavr KumarSean KucerSze Yu WangVaidehi BulusuVasanth KumarGrace JangPeter ZhangPeer ReviewLayout EditorsSarah Baig*Amanda WongAnne FogartyAnthea LiDavid LyuEdgar Hildebrandt RojoInga SchulzOliver McNeilOwen YeungChelsea Gomez-Moreno*Anita MegerdichyanChristina OwenChristina XuHannah HeinrichsNatalia Ramirez*Department heads2Berkeley Economic Review

TABLE OF CONTENTS457101316From the Editors’ Desk19A World Without Coffee:The Story Behind a PossibleImpending Coffee Crisis22America is Leaking: Howto Repair the Federal WaterPolicy?The Good, the Bad, and theUgly Produce Movement“Water Finds the Leak”:How Federal and StateGovernments Lost Billionsto Pandemic Aid FraudSpring 2021 Essay Contest23The Macroeconomicsof Happiness: A Case Studyof BhutanSpring 2021 High SchoolContest24Retirement Accountsand Overworked Drivers:The Potential of NudgeTheoryBerkeley Economics Review’sSpring 2021 Journal PreviewMission Statement: In Berkeley Economic Review, we envision a platform for the recognition of qualityundergraduate research and writing. Our organization exists to provide a forum for students to voicetheir views on current economic issues and ultimately to foster a community of aspiring economists.Disclaimer: The views published in this magazine are those of the individual authors or speakers anddo not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the UC BerkeleyEconomics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.3econreview.berkeley.edu

FROM THE EDITORS’ DESKDear BER Reader,When Berkeley Economic Review began five years ago as a humble studentorganization at UC Berkeley, none of its ten members could have imagined theastronomical growth it would experience in only a short time. BER has since becomea global phenomenon: our 90 staff members, tens of thousands of monthly readers,and countless journal submissions come from every corner of the globe. We have alsoexpanded from producing a peer-reviewed undergraduate journal to generating aconstant stream of original articles written by our staff, some of the best of which canbe found on the pages that follow.BER has changed immensely since 2016, but the world around us has changed evenmore. No event in the post-war era has reshaped and challenged the global economyas rapidly as the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast to the optimism of continuedeconomic growth in 2016, the world today continues to experience massiveunemployment and dramatic loss of human life due to the virus.Our team of young economists has closely watched these events unfold, and has neverstopped analyzing the world as it is today and debating what it could be tomorrow.From pandemic aid fraud to alternative methods of assessing economic growth, thearticles before you encompass a wide array of pressing economic issues, and we hopeyou will find them as fascinating as they are informative.We at Berkeley Economic Review have worked tirelessly this semester to produce animmense supply of insightful and timely content for you, dear reader. It is with greatexcitement that we present to you the 6th issue of our magazine, Equilibrium.Sincerely,Charles McMurry & Parmita DasEditors-in-ChiefBerkeley Economic Review4Berkeley Economic Review

A World Without Coffee:The Story Behind a Possible Impending Coffee Crisiswhen plummeting demand for coffee led to subsequentprice drops in the crop. This bankrupted these plantationstyle coffee production facilities and led to the Colombiangovernment stepping in and purchasing coffee fields fromthe owners. With influence and help from the newlyformed Fedecafé (National Federation of Coffee Growersof Colombia), the Colombian government split the coffeefields into smaller plots to give small farmers the abilityto cultivate other crops alongside coffee in order to betterprotect these farmers against price fluctuations.by Ekaterina YudinaCoffee’s prevalence in our world cannot be overstated. Inthe United States alone, nearly 400 million cups of coffeeare consumed daily, most of which stem from importedcoffee beans. The U.S. is the second largest importer ofcoffee in the world, accounting for nearly 15 percent of the175 million 60 kg bags of coffee beans exported worldwide.Yet the countries racking up the largest amount of coffeebean exports (Brazil, Colombia, and Honduras) have had aslew of issues to do with adjustments to climate change, thecoronavirus pandemic, and as a result, problems such aslabor shortages. With the pandemic’s effects on the coffeeindustry still in full force and climate change projected toget worse in these exporting regions, many argue that theworld is on the cusp of a coffee crisis.More protection against demand fluctuations came withthe 1962 International Coffee Agreement (ICA), which,when signed by the 69 participating countries (whichincluded all major importers and exporters of coffee), seta price minimum for coffee exportation. This agreement,initially spurred on to deter Latin American countries fromMarxist influences, allowed for coffee prices to recoverfrom the Great Depression and Second World War andresulted in a thriving coffee industry in Colombia thatbenefited small farmers immensely. In essence,coffee supported Colombia, with some evencrediting the establishment of industriessuch as Aerolíneas Centrales deColombia or ACES (Colombia’sbrief venture into the airlineindustry) to the favorable economicconditions fostered by relatively highand stable coffee prices. This economicprosperity, however, was short-lived. Bythe end of the 1980s, the ICA collapsed andwith it vanished the price minimum on coffeeexports. As a result, new producers (many of themconcentrated in Asia) flooded the market with cheap coffee,and smallholder farms in Colombia struggled to competeagainst the low prices.A Brief History of the World CoffeeIndustryThe European world was only introducedto the coffee bean in the 17th century, butits immediate success and skyrocketingdemand led to its planting in nearlyevery colonial outpost. Coffee beangrowth and exportation concentrated inSouth American countries (at the timeSpanish colonies) due to shocks in coffeeproduction elsewhere, notably in Haiti inthe form of the late 18th century HaitianRevolution (and subsequent loss of free slavelabor in Haiti’s coffee industry) and in Ceylondue to an appearance of the Coffee Leaf Rust Disease thatdecimated coffee plantations. By the early 20th century,the top three exporters of coffee were the top exporterswe recognize today: Brazil, Colombia, and Costa Rica.Increased U.S. demand for coffee in the late 19th and early20th centuries cemented the grasp of the coffee industry onthese countries as well, with coffee cultivation replacing thefarming of other crops such as cacao and tobacco.Taking a closer look at Colombia’s history of coffeeproduction and impacts of the industry on its economycan help explain why the current threats of climate changeand the coronavirus pandemic are and will continue topose disastrous consequences. Colombia’s initial mannerof coffee cultivation followed the Spanish colonialhacienda system, which exploited native workers on largescale plantations. This system was profitable under theconditions that prices on coffee were high, which wasensured as long as demand was relatively high as well. Inthe 1920s, the U.S. accounted for 80 percent of the world’sdemand for coffee, and as demand was high, prices werehigh and stable as well. The bitter side of this came at theend of the decade with the onset of the Great Depression,The 2009 Colombian coffee crisis, caused by extremeweather and a bout of the Coffee Leaf Rust Disease, broughtthe struggle of small coffee farmers to the surface whenColombia’s crop of coffee was decimated. Farmers andworkers in the coffee industry went on strike and demandedmore financial support from the government, even going sofar as to demand an establishment of a price minimum. TheColombian government increased subsidies to the industry,but were unable to set a price minimum on exports, whichis still unlikely to happen without another rendering of theICA.5Now coffee prices continue to fluctuate, with currentprices below what many farmers need to break even.Many Colombian farmers have thus been forced to replacetheir coffee cultivation with the growth of other crops likebananas and plantains in order to sustain themselves andtheir families. This poses a threat to the future of the coffeeindustry as a whole in Colombia, and could result in futureeconreview.berkeley.edu

coffee shortages likely to be exacerbated by climate changeand consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.Climate Change’sCultivationImpactonat greatest risk for being negatively impacted by climatechange. In order to ameliorate the effects of climate change,many have argued that governments should take action tohelp protect their countries’ coffee industries. Collectingdata and doing further research on changes in coffeecultivation and analyzing specific regional impacts wouldhelp with formally diagnosing the problems many smallcoffee growers currently face, and subsequently developingtechnology such as shade trees based on data and research incoffee-producing regions is a first step suggested by climatechange experts. Subsequently making said technology andresources physically and economically available to smallscale farmers is imperative in order to ensure not only theeconomic well being of those in the coffee industry but tocontinue coffee production as a whole.CoffeeClimate change poses a variety of issues for coffee cultivation,exacerbating the already far from ideal economic conditionsfor small coffee farmers. The two coffee bean species ofinterest to exporters (the ones that make up the majorityof coffee consumed in the world), Arabica and Robusta, areparticularly vulnerable to temperature variations. Arabicaproduces a higher quality taste than Robusta beans, but thiscomes at the tradeoff of being more sensitive to temperatureand rain conditions. The Arabica crop is notably sensitivein its growth, requiring conditions of 18 to 21 degreesCelsius, specific amounts of rain and dry seasons, and acombination of warm days and cool nights. Looking againat Colombia’s coffee industry, climate change in regionssuch as the coffee rich zona cafetera (also known as the“Coffee Axis”) has pushed farmers to grow their crops athigher elevations in an attempt to preserve the finickytemperature range. With higher elevationscome less available land to cultivate, reflectedin the 7 percent fall in land use in the zonacafetera since 2013. Land available for coffeecultivation is expected to continue to fallworldwide as well; studies predict that by2050, the amount of land usable for coffee willbe half of what it is today.COVID-19’s Effect on Labor in the CoffeeIndustryThough the effects of the coronavirus pandemic are notexpected to last permanently, they have only exacerbatedthe current coffee crisis. The pandemic has hit larger coffeefarms from the labor side, as coffee pickers havebeen much harder to hire and incentivizingpickers with higher wages is currently impossibledue to low coffee prices. Conditions for coffeepickers are far from ideal during a pandemic, aspickers often come from various regions and notall adhere to sanitary conditions such as wearingface coverings. Despite efforts to enforce strictersanitary conditions, the measures have failed toattract sufficient numbers of workers in countriessuch as Colombia, despite the unemployment ratebeing nearly double that of the previous year.The effects of climate change will weighheavily on the 500,000 small coffee farmsand their respective cultivators such as thosein Colombia. Colombian coffee culture isimperiled by inabilities of farmers to adaptto climate change, due to the combination ofnew ecological hazards and existing economichardships. Coffee growers have been working tofind solutions to adjust to the difficulties posed by warmertemperatures, including farming more temperature andpest resistant varieties of Arabica beans, moving operationsfurther uphill, and investing in shade trees to keep thecrops cool. Though these solutions are innovative, they aretemporary in nature and are costly to small farmers. Nearly60 percent of coffee species are expected to go extinct inthe next century, putting at risk the prospect of cultivatingless used but more climate resistant Arabica varieties.Moving operations uphill and installing shade trees aresolutions often unavailable to small farmers due to costbarriers. Along with low coffee prices due to the absenceof an export price minimum, Colombian farmers areheading towards the path of no longer being able to affordto cultivate coffee at all, which could send the world into afull-blown coffee shortage crisis given Colombia is one ofthe largest exporters of Arabica coffee.The story of smallholder farmers versus impending climatechange effects is not just isolated to Colombia. 25 millionfarmers cultivating small-scale coffee plots, many of whomare living in poverty, account for 80 percent of the world’scoffee production, and it is these same farmers that areLabor shortages in the coffee industry are alreadyfrequent. Pickers are not afforded a fixed income,job security, or health insurance. Thus experts suchas Fernando Morales de la Cruz of the Café for ChangeInitiative argue that labor shortages are to be expectedunless a different business model is adopted in the coffeeindustry. The pandemic has shed light on the fragility oflabor supply in the coffee industry, contributing to growingfears over a potential coffee shortage or further crisis.Worries about an upcoming economic and/or ecologicalcrisis in the coffee industry are not unfounded, especiallyin considering the industry’s condition in large exportingcountries such as Colombia. With prices kept low fromcheap foreign competition and no plan to restore the priceconditions of the ICA, both small and large coffee producersare forced to face issues such as climate change and laborshortages under crippling budget constraints. Whetherthe solutions to these issues lie with the governments ofcoffee producing countries in solutions such as subsidizingclimate change battling technology to small coffee farmersor more globally with large importers and exporters ofcoffee potentially setting a new export price minimum,action must be taken to protect the coffee industries inlarge exporting countries in order to avoid devastatingshortages.6Berkeley Economic Review

America is Leaking:How to Repair the Federal Water Policy?By Nicolas Dussauxdifferently; large cities where middle class populations livedchose to move to suburban areas, emptying city centers.The direct consequence of this decrease in the populationof city centers was a concentration of the financial burdenof infrastructure maintenance, on the generally well less offpopulation that stayed.“There is nothing more useful than water: but it willpurchase scarce any thing; scarce any thing can behad in exchange for it.” These words, from the famouseconomist Adam Smith, sound like a grim predictionas we walk into the 21st century. A number of crucialgoods and materials, on which the American economyrelies heavily, are becoming scarce by the day, and maywell become increasingly expensive. The list is long, andincludes rare metals, raw earth materials, sand, and othernatural resources that our industrial processesconsume in large quantities. Water is oneof them, and it might not be because theresource disappears, but because the USinfrastructure system is not up to the taskanymore.In face of this problem, water utilities had no other choicethan to raise water bills, making their customers bear thebrunt of the problem. The increase in rates was not enough tocompensate for the lost revenue, leading to a degradationof the quality of service, provoking a number ofevents referred to as “utilities disasters.” Themost well known of those was the Flintdisaster, a lead contamination thatlasted almost five years and provokednation-wide outrage.Besides utility disasters, the US still hashigh levels of non-revenue water,water that is not billed to customersbecause it is lost in the network,mostly because of pipe breakages.The American Society of CivilEngineers estimates non-revenuewater to amount to six billion gallonsper day. The EPA estimates thisnumber to be approximately 16% ofthe total treated water across utilities.This loss in production efficiency issector-specific but should raise aquestion: can our utilities afford tolose so much of their output? Theanswer is no, especially when thecost is borneby less well-off populations. Thedisproportionate impact ondisadvantaged populationsprompted the need for areflection on water equity andon the economicnature of water. Although it isreferred to by the OECD as an economic good,developed countries tend to consider water as a public good,and in some cases, a right. From an economic standpoint,water treatment and distribution infrastructure can beunderstood as a merit good. This concept, introducedby economist Robert Musgrave, characterizes goods forWhile California has been grappling withthe issue of water scarcity since itdeveloped intensive farming duringthe exploration of the West, otherareas in the US have always hadaccess to reliable water resources. Suchcommunities were part of the collectivenational building effort during the 20thcentury. Between the end of the SecondWorld War and the 80s, the number ofwater public infrastructure projectsshot up, based on a model of constanteconomic development and evergrowing population. This assumptionwas stated clearly by Gilbert White,the director of the President’s WaterResource Policy Commission,tasked with elaborating a waterpolicy for Americans in 1950. Ifthis assumption still held true,this would strengthen the case forcontinuing to build large andresilient infrastructure systems as was the case inthe largest cities in the US at that time.However,despite the fact that the population of the United Stateskeeps growing, the distribution of the population drasticallychanged in recent years. Researchers from Duke Universityshowed that between the 50s and today, populationsmassively moved. Different regions were affected7econreview.berkeley.edu

radical intervention of the Federal government. One wayto solve this problem would be to take action to fosterpopulation growth and reinvest these areas. Such ideas arechampioned by Matthew Yglesias, the founder of Vox, inhis book One Billion Americans: The Case for ThinkingBigger. Indeed, a rejuvenated and more dynamic Americaneconomy, supported by a larger population, would certainlyallow utilities to support the costs of both expandinginfrastructure and fixing the existing problems. However,triggering population growth is neither easy nor withoutconsequence and is not merely an economic decision.Some cities had foresight and anticipated the shrinking oftheir populations, therefore carried out capital reductionprojects to alleviate the operations and maintenance costsof their water grid and their sewer systems.which free-market conditions will lead to a consumptionlower than the optimal social amount. Such an outcomegenerally arises from ignorance on the consumer’s end, orfrom a misestimation of the value of the good. Namely, thepositive externalities and spill-over effects of effective waterinfrastructure tend to be under-estimated. The tendency totake infrastructure for granted, and to leave large publicexpenditures to the next administration, led a numberof water systems to wear out over time. The gap betweenavailable financing and actual utilities investment has beenwidening over the years, and the American Water WorksAssociation estimates that a 1 trillion in investment willbe needed over the next 25 years to maintain the currentlevels of service.There is therefore a need to find new financing mechanismsthat would allow utilities to rely less on the rates they chargetheir customers. Moreover, as a graduate student at DukeUniversity recently outlined, it has become increasinglydifficult for utilities to borrow the funds necessary to fundthese capital development projects and refurbishment.Indeed, a study of the grades attributed by Standard andPoor’s to the bonds emitted by local governments of 25 citiesin Pennsylvania, showed that the trust of investors in theability of utilities to refund the loans gradually has declinedfrom 1990 to 2020. This degradation of trust is doubly badnews for utility companies: it makes the financing harder tofind, and significantly raises the interest rates on the capitalborrowed. This in turn forces an increase in water servicerates.“For some smaller andremotecommunities,decentralizedwatertreatment is recognized as amore relevant and efficientsolution than large-scale,hardly adaptable concretestructures that can handlehumongous inflows andoutflows.”Another way to increase the resilience of the Americanwater grid could be to bet on technological progress, andmore importantly, on a shift in the paradigm of watertreatment and distribution. For some smaller and remotecommunities, decentralized water treatment is recognizedas a more relevant and efficient solution than large-scale,hardly adaptable concrete structures that can handlehumongous inflows and outflows. These decentralized,sometimes mobile, solutions are relevant in both water andwastewater treatment, and alleviate the strain on sewers incase of huge stormwater inflows. These extreme weatherevents, that are unfortunately increasingly common asclimate change becomes a tangible reality, often overwhelmthe wastewater systems and have caused utilities to pay morethan 2 million in fines for Combined Sewer Overflows(CSO) over the last 30 years in New England alone.Like the suburban flight, this situation puts low-incomehouseholds under financial strain, who saw an inflationadjusted yearly increase of 5% in utility rates, compoundingto make the burden heavier each year. In North Carolina,one of the four states where the research team of DukeUniversity concentrated their efforts, households makingthe minimum wage have to work the equivalent of 4 daysper month to just afford their water bill.The water industry is also not impervious to the datarevolution, and a number of firms have developed digitalsolutions allowing utilities to model their flows and usecutting edge predictive analytics to optimize the watertreatment asset management. Such innovations, whencorrectly implemented, can allow utilities to save money onoperations and maintenance (“O&M”) and schedule theirThis situation is hardly sustainable and calls for more8Berkeley Economic Review

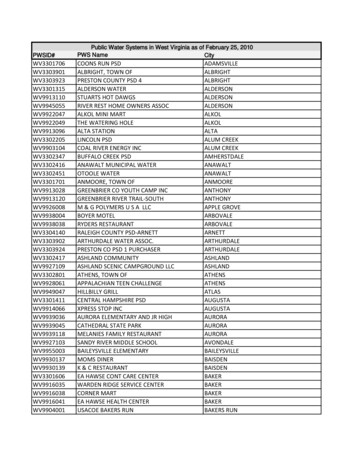

bills could help utilities to maintain their level of revenuewithout directly penalizing less well-off individuals. Thisredistributive policy could not only lead to greater equity,but could also help water utilities to recover more thantheir cost and carry out renovation projects.capital expenditures in a manner that reduces risk anduncertainty. However, models are only as good as the datathey use, and even if these innovations change the face of thewater treatment and distribution industry and dramaticallylower water rates, they still require heavy investments toimplement the advanced metering infrastructure that willbe able to feed models with relevant information. Indeed,old water transmission systems were not designed tomeasure flows and utilities need to invest in new metersand pumps to be able to collect the data and transmit it.However, the core problem is the obsolescence of theAmerican water grid, and that need must be addressed. Theidea that infrastructure is a “bipartisan issue,” for whichpolitics are not an obstacle, proved to be a misconceptionunder the Trump administration. The error the Trumpadministration made was to think about the Federalgovernment as a planner that merely needed to raisemoney to build and own infrastructure. The true role ofthe federal government is the one of a grant-maker, and thespecifics of the project are often better determined at thelocal scale, far away from Washington D.C. The primaryrole of local authorities proved to be an obstacle for Trump,as some of his openly anti-immigration declarations havedrawn hostility from local officials, alienating him fromseveral key partners. The need for better infrastructurewas a theme during the 2020 Presidential race, but thefailure of the Trump administration to realize therewas a need to shift the role of the federal government toimplement a top-down approach sets the challenge for theBiden administration. Currently owning only about 6%of the national infrastructure (BEA estimate), the federalgovernment will have to transition from a grant-makerrole to a real infrastructure planner mission to rely lesson states and local governments. The challenge facing theBiden administration will be both political and technical:coordinating the forces at all government levels and comeup with clever and economically sound public-privatepartnerships to finally rejuvenate the American waterinfrastructure.The increasing share of water supply that is handled by privateutilities makes little difference when it comes to addressingcrumbling infrastructure. Free-market outcomes might notbe optimal when it comes to infrastructure provisioning,and the government must often intervene on these marketsto make sure the right quantity of these merit goods issupplied. Looking at the distribution of the investmentsin water and sewer systems across the different levels ofgovernment, we see that the cost of capital is mainly borneby local governments and states. Although the FederalState contributes 25% of the total infrastructure spendingin the US, its share of investments in water utilities areapproximately equal to 3.5%. Additionally, the lawsuits andconsent decrees, resulting from the utilities failures such asFlint or the PFAS crisis in North Carolina, have worsenedthe finances of local governments which are sometimesoverwhelmed by compliance costs and lawsuit liabilities.Source:Congressional Budget OfficeIn the short-term, it becomes clear that the FederalGovernment must either get more involved to help waterutilities support their operations and maintenance costsor directly subsidize consumers’ increasing water bills.The policy to support consumers’ water consumptionwould work in the same way the government does withfood through the SNAP program. Giving vouchers tolow-income households to help them afford their water9econreview.berkeley.edu

THe MAcroeconomicsof happiness:a case study of bhutanBy Chazel HakimSituated deep in the eastern Himalayan mountains, Bhutanis often overshadowed by its more prominent neighbors:China and India. But, despite its quiet status, the country hasconstantly made headlines for a variety of socioeconomicachievements. Bhutan remains, for example, the first andonly carbon-negative country in the world, and they havealso recently prevented the COVID-19 pandemic fromoverwhelming its population, with only one Bhutanesecitizen passing away from the virus to date.Nevertheless, it is the Gross National Happiness Index(GNH), Bhutan’s main macroeconomic indicator, thatstands as the country’s most radical achievement to date.The GNH’s construction is simple: rather than measuringthe aggregate spending from a country’s population,Bhutan’s GNH seeks to measure their total happiness. The“happiness” in this case is obviously a subjective concept,but the indicators for GNH are based on tangible statisticsof measures ranging from economic development toenvironmental protection levels.Bhutan is also not the only country to have shiftedmacroeconomic analysis towards more holistic socialindicators, as several other countries such as the UnitedKingdom and New Zealand have incorporated wellnessgoals into their policies. However, no country has put theideas of happiness as central to their public policy decisionsas Bhutan does through their GNH. Particularly with thecountry’s recent success during the pandemic, it then mightbe worthwhile to ask: has GNH actually played a significantrole in helping Bhutan thrive?Bhutan’s Gross National HappinessIndexThe idea of a GNH index stretches back to 1972, when oneof the founders of the European Union, Sicco Mansholt,first came up with the idea as a critical response to theworld’s traditional budget reliance on Gross DomesticProduct (GDP). For those unfamiliar with GDP, it is simplya measure of the monetary value of a country’s spendingon goods and services, but its real worth lies in its use as anquantitative indicator of a country’s growth and nationalincome. Policymakers rely on GDP to make informeddecisions about policy, but over the years, many havecriticized how GDP calculations ignore crucial aspects ofpeople’s lives, including life-satisfaction and environmentaldegradation metrics (read this BER article for a detailedexplanation of criticisms of GDP).Compared to GDP’s technical measures of spending andoutput, Bhutan’s own GNH index takes a more holisticapproach to measuring a country’s growth. One of its moststriking differences comes down to its equal weightingof economic and non-economic aspects of the country,as exempl

Berkeley Economic Review econreview.berkeley.edu Mission Statement: In Berkeley Economic Review, we envision a platform for the recognition of quality undergraduate research and writing. Our organization exists to provide a forum for students to voice their views on current economic issues and ultimately to foster a community of aspiring .