Transcription

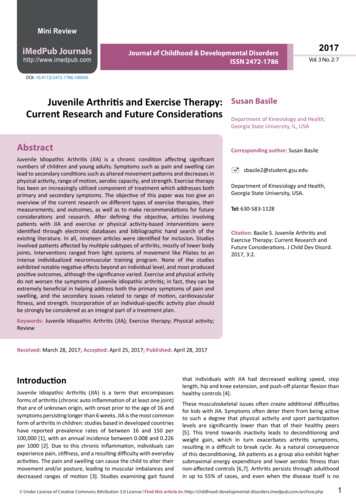

Mini ReviewiMedPub Journalshttp://www.imedpub.comJournal of Childhood & Developmental DisordersISSN 2472-17862017Vol. 3 No. 2: 7DOI: 10.4172/2472-1786.100045Juvenile Arthritis and Exercise Therapy:Current Research and Future ConsiderationsAbstractSusan BasileDepartment of Kinesiology and Health,Georgia State University, IL, USACorresponding author: Susan BasileJuvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) is a chronic condition affecting significantnumbers of children and young adults. Symptoms such as pain and swelling canlead to secondary conditions such as altered movement patterns and decreases inphysical activity, range of motion, aerobic capacity, and strength. Exercise therapyhas been an increasingly utilized component of treatment which addresses bothprimary and secondary symptoms. The objective of this paper was too give anoverview of the current research on different types of exercise therapies, theirmeasurements, and outcomes, as well as to make recommendations for futureconsiderations and research. After defining the objective, articles involvingpatients with JIA and exercise or physical activity-based interventions wereidentified through electronic databases and bibliographic hand search of theexisting literature. In all, nineteen articles were identified for inclusion. Studiesinvolved patients affected by multiple subtypes of arthritis, mostly of lower bodyjoints. Interventions ranged from light systems of movement like Pilates to anintense individualized neuromuscular training program. None of the studiesexhibited notable negative effects beyond an individual level, and most producedpositive outcomes, although the significance varied. Exercise and physical activitydo not worsen the symptoms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis; in fact, they can beextremely beneficial in helping address both the primary symptoms of pain andswelling, and the secondary issues related to range of motion, cardiovascularfitness, and strength. Incorporation of an individual-specific activity plan shouldbe strongly be considered as an integral part of a treatment plan. sbasile2@student.gsu.eduDepartment of Kinesiology and Health,Georgia State University, USA.Tel: 630-583-1128Citation: Basile S. Juvenile Arthritis andExercise Therapy: Current Research andFuture Considerations. J Child Dev Disord.2017, 3:2.Keywords: Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA); Exercise therapy; Physical activity;ReviewReceived: March 28, 2017; Accepted: April 25, 2017; Published: April 28, 2017IntroductionJuvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) is a term that encompassesforms of arthritis (chronic auto inflammation of at least one joint)that are of unknown origin, with onset prior to the age of 16 andsymptoms persisting longer than 6 weeks. JIA is the most commonform of arthritis in children: studies based in developed countrieshave reported prevalence rates of between 16 and 150 per100,000 [1], with an annual incidence between 0.008 and 0.226per 1000 [2]. Due to this chronic inflammation, individuals canexperience pain, stiffness, and a resulting difficulty with everydayactivities. The pain and swelling can cause the child to alter theirmovement and/or posture, leading to muscular imbalances anddecreased ranges of motion [3]. Studies examining gait foundthat individuals with JIA had decreased walking speed, steplength, hip and knee extension, and push-off plantar flexion thanhealthy controls [4].These musculoskeletal issues often create additional difficultiesfor kids with JIA. Symptoms often deter them from being activeto such a degree that physical activity and sport participationlevels are significantly lower than that of their healthy peers[5]. This trend towards inactivity leads to deconditioning andweight gain, which in turn exacerbates arthritis symptoms,resulting in a difficult to break cycle. As a natural consequenceof this deconditioning, JIA patients as a group also exhibit highersubmaximal energy expenditure and lower aerobic fitness thannon-affected controls [6,7]. Arthritis persists through adulthoodin up to 55% of cases, and even when the disease itself is no Under License of Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License Find this article in: om/archive.php1

ARCHIVOS DEMEDICINAJournal of Childhood & nger present, there are consequential long-term effects suchas restrictions in joint motion, contractures, and local growthdisturbances, and resulting limb length discrepancies [8].The main treatment for JIA is medication, typically in the formof anti-inflammatories. These can range from over-the-counterNSAIDs to more powerful Disease-Modifying Anti-RheumaticDrugs (DMARDs) and corticosteroids. Less commonly surgery,splints, and orthotics are used to correct deformities or postures.In the past decade, exercise has become increasingly recognized asa beneficial and vital component of a holistic treatment plan. Themost common exercise-centred therapy for JIA initially involvedtypes of aquatic exercise, on the basis that it would be less likelyto aggravate joint pain. Eventually, as it was demonstrated thatthese types of programs could often be implemented withoutsignificant increases in pain, methods incorporating weightbearing and strength exercises became increasingly common aswell, as have fitness systems like Pilates and qigong.A physical activity program is essential to break the cycle ofinactivity and deconditioning described previously, improvingcardiovascular and musculoskeletal strength to levels morecomparable to that of their non-diagnosed peers. Engagementin exercise is also beneficial for the same reasons it is in healthychildren and adolescents, primarily among them impact loadingfor bone health, which is of increased significance given thatthe joints are primarily affected [9,10]. Part of the governmentinitiative ‘Healthy people 2020’ includes a focus on keepingindividuals with chronic conditions as healthy and active aspossible [11]. Given that youth patterns of physical activity tendto carry over into adulthood [12-14] and the fact that arthritispersists into adulthood more often than not, developing effectiveexercise habits in these patients has clear short and long termimplications.This aim of this paper is to survey the current research on exerciseinterventions in children and young adults with JIA and examinethe following: (1) What are the demographics of the populationsbeing studied? (2) What types of interventions are being studied,and what measurements are being employed to determine theefficacy of these interventions? (3) What are the outcomes and(4) What are the future applications and implications of thesestudies?Paper IdentificationElectronic databases PubMed, CINAHL, Science Direct, and Webof Science were searched between 1990 and July 2015. Keywordsincluded combinations of ‘juvenile idiopathic arthritis’, ‘chronicjuvenile arthritis’, ‘juvenile rheumatoid arthritis’, and ‘exercise’,‘endurance’, ‘strength training’, ‘aerobic training’, ‘physicaltherapy’, ‘physical activity’, ‘aerobic’, ‘hydrotherapy’, and‘aquatic therapy’. A hand search of the bibliographic references ofthe extracted articles was conducted to capture any publicationsmissed by electronic databases. To be included, articles had to:Incorporate a juvenile population that had an identified subsetof juvenile idiopathic arthritis (polyarticular, pauci/oligoarticular,systemic, psoriatic, or enthesis-related) and have at least onephysical-activity or exercise-based intervention with clearly22017Vol. 3 No. 2 : 7defined outcome measures. Single case and case studies wereincluded, as was a prospective study on a comparison betweenchildren who only underwent physical therapy versus childrenwho participated in sports in addition to their therapy. Table1 provides a summary of the existing literature on exerciseand sports research involving patients with Juvenile IdiopathicArthritis.Study DesignsThere were nineteen publications in total, over a 14-year timeperiod (1991 to 2015). The majority were randomized control(eleven) or pilot (five) studies, and included comparisonsof an intervention–some type of exercise therapy–to eithercontinuation of current treatment, another type of exercise, orto healthy matched controls. The most common therapies wereaquatic (hydro) therapy and/or some form of basic strength and/or aerobic training. Others included an investigation of the effectsof Pilates, qigong (a Chinese-based practice focused on postureand breathing), and a highly individualized neuromusculartraining program. Session durations all fell between 40 and 60min. Intervention periods lasted between five weeks and sixmonths, with three and six months being the most used durations.DemographicsOverall 463 female and 178 male subjects participated in thestudies. While the gender breakdown of arthritis varies withcharacteristics such as location and subset, it is generally acceptedthat with the exception of enthesitis-related arthritis, JIA is morecommon in girls. The subtype breakdown was as follows: 339 poly articular. 212 oligo/pauciarticular. 61 systemic. 28 enthesis or ‘other’. 22 psoriatic.At 51% and 32%, the prevalence of polyarticular isoverrepresented at the expense of oligo-articular-diagnosedindividuals, by at least 10% when compared to recent estimates[1]. All the subjects were affected in a lower body joint, and assuch most interventions focused on the core and lower body.Primary Assessment MeasuresThe most common survey-based measures were pain and qualityof life/functional ability scores. The use of a Visual Analog Scale(VAS) was most common for the former, as were the JuvenileArthritis Quality of Life Questionnaire (JAQQ), Pediatric Quality ofLife Inventory (PedsQL ), and the Childhood Health AssessmentQuestionnaire (CHAQ), and for the latter. The most commonphysical measurement was Range of Motion (ROM). Alsocommon were joint scores (the number of joints affected), 6 or9 min run walk tests, tests of oxygen consumption–VO2 max andVO2 peak, and isometric strength tests. Notable study-specificmeasures included gait measurements, bone mineral content,vertical jump tests, and EMG data.Find this article in: om/archive.php

Under License of Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License105427 controlTakken etal. [6]Takken etal. [16]2002200378Epps et al.200539 land/39[17]combined25Klepper[15]1999Oberg et1994al. [14]2010 control62Kircheimeret al. [11]199211AuthorBacon et1991al. [13]YearNumber ofParticipants(Control/alternativetreatment)25 poly29 poly, 23oligo, 2 sys33 poly, 224-19oligo, 10 sys,53F/35M, 12 enthesis, 1psori5-1338F/16M6 weeksAquatic exercise 2/week1.75 h stretching, ROM,strengthening exercises 0.25 h free playSporting activityPilotProspectivemonitoringsportsversus onlyPTRCTRCTPilotPilotEMGROM, mal-alignment,joint scoresJoint ROM, balance tests,timed tasks, gait analysisAssessment MeasuresJoint scores significantly correlatedwith stage of disease,not with participation in sports.Disease duration longer than10 years associated with lowparticipation in athletic activities.No significant difference in force orendurance b/w patientsand controls, same strengthtrainability,normalization of fatigue after trainingImproved hip rotationOutcomesASI (pain on motion,tenderness, swelling,Significant improvement in ASI, runwalk test, and joint count,8 weekslimitation of motion),Mixed VAS scoresjoint count, pain (VAS), 9min run walk testJoint status & mobility,Improved quality of life, no change in1/week 1 h aerobic aquatic15 weeksCHAQ, 6 min walking test,other measuresexerciseJAQQ, pain (VAS)Functional ability (CHAQ,JAFAS), Juvenile arthritisquality of life (JAQQ),Small improvement in joint status,20 1 h sessions of poolJoint status (tenderness,6 monthsphysical function,based aerobic exerciseswelling, movement),and quality of lifephysical fitness (maximalexercise test, 6 minwalking test)Disease status (CHAQ,ROM, active joints,Land -16 h sessions ofSlight increase in CHQ and meanparent/physicianmuscle strengthening &muscle strength2 weeks intensiveassessment),stretching exercisesin combined; aerobic fitness, and2 months outpatientisometric musclecombined -8 land 8endurancestrength, physical fitnesshydrotherapyimproved in both(cycle ergometer), pain(VAS)3/week low-impactweight-bearing physicalconditioning program1/week 60 min videoguided home exercise3 months8 yearsDurationInterventionDesign40 min/2 week3 poly, 5 oligo,RCT (healthy strength and endurance1 psori,controls)training incorporating1 sysstatic & dynamic exercises35 poly, 11oligo, 7 sys4 poly, 4 oligo,3 sysSubset5-133 poly, 4 oligo,38F/16M3 sys8-1723F/2M7-156-177F/3M4-137F/4MAgeGenderTable 1: Summary of exercise intervention studies for individuals with juvenile arthritis.Journal of Childhood & Developmental DisordersISSN 2472-17862017Vol. 3 No. 2 : 73

419AuthorMyer etal. [12]Year2005Singh2006 Grewal etal. [18]4 (1 withJIA)3316 controlFragala2009 Pinnkhamet al. [20]Lelieveld2010et al. [21]80Singh412007 Grewal etaerobic/39al. [19]Qi gongNumber F/4M2 y/o F8 -1664F/16M8-115F/4M10FAgeGender9 poly, 20oligo, 4 sysoligo34 poly, 18oligo, 7 sys,11 enth, 8psori, 2 other3 poly, 4 oligo,2 sysOligo/pauciSubsetRCTCase SeriesRCTPilotCase studyDesign6 months17 weeksInternet-based programteaching aboutbasics of JIA, PT and itsbenefits, goal setting, etc.12 weeks12 weeks5 weeksDuration1/week 60 min poolexercise1/week 60 min PT at home3/week 45 min highintensity aerobic programvs. qigong2/week neuromusculartrainingwarmup, plyometrictraining, corestrengthening2/week sessions poolwarmup,aerobic gym stations(fitball, cycle, treadmill,strength exercises)InterventionSlight decrease in energy cost oflocomotion,increase in VO2 peak, anaerobic legpowerCHAQ, JASI, energy costof locomotion, vo2peakpeak/mean musclepowerVo2submax/peak, peak improved physical function (C-HAQ) w/power, physical functionno difference(C-HAQ),between groups, no significant changeQOL, HRSQOL, VASin any fitness parametersOccupationalPerformance measure(COPM), GMFM-66,PediatricEvaluation of DisabilityInventory, mobilityfunctional skills, andClinically significant improvement incaregiver assistance,QOL and ROM,energy expenditure,observational gait scale,extension, and weight bearing oninvolved limbfunctional reach test,timed single leg stance,floor to stand,manual muscle testing,isometric musclestrength, passive ROM,numerical pain scale,JAQQIncreased physical activity, time spentC-HAQ, physical activityon moderate t(diary), aerobic exercisevigorous activity, and days onecapacity (bruce treadmill week hours of moderate to vigoroustest)PA, increased max endurance time ontreadmillIncreased hamstring strength andhams: quads,movement towards more normal gait,decrease in peak force on drop/jump,improved stabilityOutcomesPain (VAS), ROM, gait,landing technique,vertical jump test,knee ext/flex strength,postural stabilityAssessment MeasuresARCHIVOS DEMEDICINAJournal of Childhood & 17Vol. 3 No. 2 : 7Find this article in: om/archive.php

12 poly, 24oligo, 14 sys50Mendonca 25 standard8-182013et al. [23] exercise/25 32F/18Mpilates Under License of Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License8 weeks6 weeks12 weeks244/week aerobic walking,polyarticular,8-16RCT (healthydaily ROM exercises16 oligo,29F/18Mcontrols)3/week 40 min home2 sys, 1 enth, 4based resistance trainingpsori3/week 45 min resistantbike ergometer, stretching(both groups)group 1: kneestrengthening/ROMexercisesgroup 2: proprioceptive/balance exercises30Baydogan152015et al. [26] strength/15balance6-1821F/9M16 poly, 11oligo, 3 psoriRCTRCT50Dogru Apti201420 healthyet al. [28]controls9-2141F/13M29 poly, 15oligo,4 enth/psori12 weeks5421 controlSandstedtet al.2013Pilot3 poly, 3 oligo,1 enth3/week exercise programincludingjump rope, musclestrength/core exercises &free weights10-174F/3M6 weeks7Van Oortet al. [24]20133/week 40 min homebased resistance training(band and body weight)12 weeks3 monthsDuration6 months1/week 20-45 minindividualized land-basedhome exercise(strengthening, posturalexercises, functionalactivities)4/week at hospital3/week 20 min of strengthexercise, includingjump rope, core, arm,and shoulder strengthexercisesIntervention2/week 50 minRCTRCT31 poly, 17oligo, 6 enth/psori9-2141F/13M5421 controlSandstedtet al.[9]2012RCT5-1729F/4M46 poly, 30oligo, 3 sys, 1psori9338 controlTarakci etal. [22]2012AgeGenderDesignAuthorYearSubsetNumber ofParticipants(Control/alternativetreatment)Total body BMD increased in exercisegroupIncreased physical function and qualityof life in exercise group,decreased pain in control groupOutcomesINTRAGROUP: Improved strength in allpain, passive ROM,except hip/ankle,muscle strength, balance,increased proprioceptionfunctional ability,INTERGROUP: improvements in allwalking stair climbingaspects in group 2 except NRS, CHAQ,PROM, and hip ext/knee flexQuality of life (PedsQL),Improved pain and CHAQ scores,functional ability (CHAQ),improved ROM/wpaingreater improvements in pilates group(VAS), ROMPain, inflammation,muscle thickness (vastuslateralis andIncreased vastus lateralis thicknessbiceps brachii), musclestrength, functional ability(CHAQ)ROM, balance, musclestrength, grip strength,Significant increase in hip and kneestep test,extensor strength,quality of life (CHAQ,small increase in CHAQCHQ-C87)Significantly increased ROM inshoulder (abd/flex), wrist (flex/ext),elbow (flex), hip (flex), knee (flex/ext),VO2 peak, hrs , RER, O2and ankle (PF/DF).uptake, ROMmoderate increase in VO2 peak, RER,VO2at, resting hrs, resting sys BP,VEpeak, Max h, exercise durationFoot BMC and BMC Zscore6 min walk test, CHAQ,pain (VAS), PedsQL,Assessment MeasuresJournal of Childhood & Developmental DisordersISSN 2472-17862017Vol. 3 No. 2 : 75

ARCHIVOS DEMEDICINAJournal of Childhood & tcomesAll of studies included demonstrated positive outcomes on somelevel, though the degree of significance of these outcomes wasquite varied. Many studies took care to note that overall paindid not increase, and no group measure regressed over the studyperiod. However, there were isolated instances of increasedpain or discomfort, associated with individuals identified asexperiencing more severe cases. These cases were either notedin results reporting, or in reporting subject drop out or loss tofollow up.Physical function, quality of life, and range of motion of atleast some joints improved in essentially all studies where theywere measured, significantly in many of them. Groups thatwere engaged in land-based aerobic activities showed moreimprovement in the various aerobic outcome measures thanthose in hydro or movement centred therapies. Although strengthmeasures tended to improve slightly in cases when measured,results tended more towards levels of significance when this wasa focus of the program, and at the muscles that were the focus ofthe program. Gait measures trended towards normal levels, andin the study examining bone content, total body bone mineraldensity increased in the exercise group.Case StudiesA prospective overview of arthritic youths participating insports activity over an eight year period found pain to bemore correlated with the disease stage than with their level ofparticipation in sports 11. Additionally, increased severity andlength of disease preceded a decline in activity, as opposed to achange in activity level resulting in a change in severity. A secondcase study involved a highly individualized training program for aten-year old with a quiescent case of bilateral knee arthritis [12].A training program was created to improve the subject’s landingtechnique, core strength, and balance and coordination, in orderto address biomechanical and neuromuscular imbalances anddeficits that would prevent her from safely participating in ahigh-impact sport (basketball). Following training, the subject’sheel strike and step width were brought to within normal limits,peak force and imbalance on a box jump landing decreased, andflexor/extensor strength ratios and balance measures convergedto normal and equal levels.DiscussionThe overall quality of existing research investigating the efficacyof exercise programs in mediating the symptoms of children withjuvenile arthritis is generally high. Most studies involved a largesubject pool, included children of both sexes, and individualswith varied types of arthritis. Additionally, the studies werefairly consistent in choosing outcome measures (CHAQ, VAS,joint ROM), making comparison of results a more productiveendeavour. This review shows that including an exerciseprogram as a component of treatment for juvenile arthritis isa worthwhile endeavour. However, additional research wouldbe beneficial in that it could provide more definitive results. In62017Vol. 3 No. 2 : 7addition, more information would allow for the development ofpatient-specific programs, pairing exercises and programs withparticular types or severities of arthritis. For example, given theexisting research, a water-based program would likely be morehighly recommended for children with more severe and multijoint lower body arthritis. Conversely, children with more mildarthritis, or fewer involved joints may be given more freedomin choosing a program. This might increase retention, as it hasbeen shown that enjoyment and engagement with an exerciseprogram increases participation rates.Essentially all of the present studies examining the effectsof exercise on children with idiopathic arthritis have variedpopulations that include individuals with polyarticular, oligo/pauciarticular, systemic, and enthesitis-related and psoriatic JIAin the same study. Aside from single incidence studies, there wereno articles that applied an intervention to a specific subtype.Therefore, we don’t know whether exercise efficacy varies basedon arthritis classification, since it is difficult to determine in asignificant manner when all of these patient populations aretreated as one entity. There are multiple reasons why it would bebeneficial to design a study to examine the effect of an interventionon a specific subtype. For example, oligoarticular arthritis tendedto be somewhat diminished in its study representation comparedto its prevalence. This is potentially due to its higher prevalencein age ranges not captured, as study age ranges typically startedat at least six. Separating by subtype would also be particularlyuseful in the cases of systemic arthritis, where patients tend tobe less tolerant of more strenuous and weight bearing exercise.In this case, research may choose to focus more on combinationsof medication and activity, or on less impact-heavy systems likePilates and yoga.In addition, studies mostly focused on patients who had involvedlower body joints. While this coincides with trends in the overallpopulation, and affectation of the lower body tends to have moreimpact on mobility and gait, there are still a significant numberof individuals with upper body affected JIA, particularly in thehands. Potential future research could examine if the aerobiccapacity of these individuals is different when compared to lowerextremity affected individuals or healthy counterparts. Upperbody individuals would also be more readily able to engage inweight bearing activity without pain, and may benefit from amore strength focused program.Some of the interventions required only once or twice weeklysessions. While this is sufficient if the exercise were purelytherapy, to see more significant physiological results, it isprobable that the exercise would have to be undertaken morefrequently. Given the depressed levels of physical activity in thispopulation, it is unlikely the subjects were being adequatelyactive outside of the sessions, and would therefore not likelymeet recommended amounts of daily activity. This is of additionalsignificance given that JIA is more prevalent in girls, who tend toexperience declines in physical activity as they progress throughpuberty, even in healthy populations [14,15]. For future studies,intervention duration of at least three months would be optimalwhen possible.Find this article in: om/archive.php

Journal of Childhood & Developmental DisordersISSN 2472-1786The reviewed articles were well-advised in their selection andapplication of outcome measures. Most employed measuresthat are universally important to arthritis patients–pain,functional ability, and quality of life. From that set, researchersadded measures that were specific to the outcomes deemedof importance, or the particular type of intervention. Whilethe subjective measures are clearly useful, it is important tocontinue to stress the use of the objective measures. Both gaitanalysis and EMG measurement were two assessment methodsthat were rarely used, but can provide unique insights into thebiomechanical and neuromuscular issues that occur with JIA[16-26]. For example, the Oberg article was able to determinethat affected joint muscles were more fatigable than healthycontrols, and that this gap was largely diminished upon training.This is certainly an area that has great potential in identifyingneuromuscular deficits and quantifying progress due to therapies.Gait analysis is important, as it is a more quantitative measure ofmobility. Additionally, for individuals who have less severe casesof arthritis, they may have goals of being able to participate incompetitive sports with their peers, but they first have to developsimilar gait and postural control before they can safely performmore complicated and energy intensive movements. Under License of Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License2017Vol. 3 No. 2 : 7ConclusionThe optimal exercise therapy program will address the patient’sposture and range of motion issues, in addition to their aerobiccapacity and strength. The former are important for pain andfunctional ability, while the latter are important for weightmanagement, functional ability, and bone health. It is alsorecommended to match the system of activity to the diseasestatus and goals of the patient. For example in extremely severecases the goal may simply be an increase in range of motion, ormore normal gait, while a well-managed or quiescent case mayaim to participate in competitive sports, with the Myer et al. [12]providing an incredibly informative blueprint on how this mightbe achieved.Encouraging exercise is a good in and of itself, with clear andwell known benefits in the general population, and youth inparticular. In children with arthritis, it can improve quality of lifeand close the gap between them and their healthy peers when itcomes to things like pain, aerobic capacity, bone health, strength,gait, and everyday functional capacity, providing them with theenthusiasm and confidence to become lifelong participants insports and exercise. The fact that juvenile idiopathic arthritispersists into adulthood in up to half of patients, underscores theneed to assist patients in finding ways to manage their arthritisand be active that are effective for them.7

ARCHIVOS DEMEDICINAJournal of Childhood & ferences1Ravelli A, Martini A (2007) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The Lancet369: 767-778.2Manners PJ, Bower C (2002) Worldwide prevalence of juvenilearthritis why does it vary so much? J Rheumatol 29: 1520-1530.3Häfner R, Truckenbrodt H, Spamer M (1998) Rehabilitation inchildren with juvenile chronic arthritis. Baillières Clin Rheumatol 12:329-361.4Hartmann M, Kreuzpointner F, Haefner R, Michels H, Schwirtz A, etal. (2010) Effects of juvenile idiopathic arthritis on kinematics andkinetics of the lower extremities call for consequences in physicalactivities recommendations. Int J Pediatr 2010: 1-10.5Cavallo S, Majnemer A, Duffy CM, Feldman DE (2014) A100: Predictorsof involvement in leisure activities among children and youth withjuvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 66: S135-S135.6Takken T, Hemel A, Net J van der, Helders PJM (2002) Aerobic fitnessin children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic review. JRheumatol 29: 2643-2647.7Giannini MJ, Protas EJ (1991) Aerobic capacity in juvenile rheumatoidarthritis patients and healthy children. Arthritis Rheum 4: 131-135.8Minden K, Niewerth M, Listing J (2002) Long-term outcome in patientswith juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 46: 2392-2401.9Sandstedt E, Fasth A, Fors H, Beckung E (2012) Bone Health in Childrenand Adolescents With Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis and the Influence ofShort-term Physical Exercise. Pediatr Phys Ther 24: 155-161.10 Burnham JM, Shults J, Dubner SE, Sembhi H, Zemel BS, et al. (2008)Bone density, structure, and strength in juvenile idiopathic arthritis:Importance of disease severity and muscle deficits. Arthritis Rheum58: 2518-2527.11 Kirchheimer JC, Wanivenhaus A, Engel A (1993) Does sport negativelyinfluence joint scores in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.An 8-year prospective study. Rheumatol Int 12: 239-242.12 Myer GD, Brunner HI, Melson PG, Paterno MV, Ford KR, et al. (2005)specialized neuromuscular training to improve neuromuscularfunction and biomechanics in a patient with quiescent juvenilerheumatoid arthritis. Phys Ther 85: 791-802.2017Vol. 3 No. 2 : 715 Klepper SE (1999) Effects of an eight-week physical conditioningprogram on disease signs and symptoms in children with chronicarthritis. J Arthritis Health Prof Assoc 12: 52-60.16 Takken T, Net J van der, Kuis W, Helders PJM (2000) Aquatic fitnesstraining for children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology42: 1408-1414.17 Epps H, Ginnelly L, Utley M (2003) Is hydrotherapy cost-effective? Arandomised controlled trial of combined hydro

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) is a term that encompasses forms of arthritis (chronic auto inflammation of at least one joint) that are of unknown origin, with onset prior to the age of 16 and symptoms persisting longer than 6 weeks. JIA is the most common form of arthritis in children: studies based in developed countries