Transcription

RACE REBELSCulture, Politics, and the Black Working ClassROBIN D. G. KELLEYTHE FREE PRESSNew York London Toronto Sydney Singapore

RACE REBELS

THE FREE PRESSA Division of Simon & Schuster Inc.1230 Avenue of the AmericasNew York, NY 10020Copyright 1994, 1996 by Robin D. G. KelleyAll rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in anyform.THE FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.First Free Press Paperback Edition 1996Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataKelley, Robin D. G.Race rebels : culture, politics, and the Black working class/Robin D. G. Kelleyp. cm.1. Afro-Americans—History—1877-1964 2. Afro-Americans—History—1964- 3. Afro-Americans—Politics and government 4. Working class—UnitedStates—History—20th century 5. Radicalism—United States—History—20thcentury I. TitleE185.61.K356 1994973′.0496073—dc20 94-27097CIPeISBN-13: 978-1-439-10504-7ISBN-13: 978-0-684-82639-4

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Permission CreditsThe Free Press and the author gratefully acknowledge permission to reprintexcerpts from the following poems, song lyrics, or book chapters.“A New Song” by Langston Hughes, The Liberator, October 15, 1932.Copyright 1932. Reprinted by permission of Harold Ober Associates Inc. Allrights reserved.“The Ballad of Ethiopia” by Langston Hughes, Baltimore Afro-American,September 28, 1935. Copyright 1935. Reprinted by permission of HaroldOber Associates Inc. All rights reserved.“Letter from Spain: Addressed to Alabama” by Langston Hughes, Volunteer forLiberty 1, no. 23 (November 15, 1937). Copyright 1937. Reprinted bypermission of Harold Ober Associates Inc. All rights reserved.“The Lame and the Whore,” reprinted by permission of the publishers from GetYour Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me: Narrative Poetry from Black OralTradition by Bruce Jackson, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.Copyright 1974 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.“Malcolm X—An Autobiography” by Larry Neal, in For Malcolm: Poems onthe Life and Death of Malcolm X, edited by Dudley Randall and Margaret C.Burroughs (Detroit, Mich.: Broadside Press, 1967), 10. Used by permission ofBroadside Press.“Romance Without Finance” by Lloyd “Tiny” Grimes. Copyright 1944,renewed 1972, Mills Music, Inc. Used by permission of CPP/Belwin, Inc., P. O.Box 4340, Miami, FL 33014. All rights reserved.“Amerikkka’s Most Wanted” by Ice Cube and Eric Sadler. Copyright 1990WB Music Corp., Gangsta Boogie Music, Warner Tamerlane Publishing Corp.,

Your Mother’s Music. All rights on behalf of Gangsta Boogie Musicadministered by Warner Chapell Music (ASCAP). All rights on behalf of YourMother’s Music administered by Warner Tamerlane Publishing Corp. Used bypermission. All rights reserved.“The Nigga Ya Love to Hate” by Ice Cube and Eric Sadler. Copyright 1990WB Music Corp., Gangsta Boogie Music, Warner Tamerlane Publishing Corp.,Your Mother’s Music. All rights on behalf of Gangsta Boogie Musicadministered by Warner Chapell Music (ASCAP). All rights on behalf of YourMother’s Music administered by Warner Tamerlane Publishing Corp. Used bypermission. All rights reserved.“It’s a Man’s World” by Ice Cube, Yo Yo, and Sir Jinx. Copyright 1990Gangsta Boogie Music. All rights on behalf of Gangsta Boogie Musicadministered by Warner Chapell Music (ASCAP). Used by permission. Allrights reserved.“You Can’t Fade Me” by Ice Cube and Eric Sadler. Copyright 1990 WBMusic Corp., Gangsta Boogie Music, Warner Tamerlane Publishing Corp., YourMother’s Music. All rights on behalf of Gangsta Boogie Music administered byWarner Chapell Music (ASCAP). All rights on behalf of Your Mother’s Musicadministered by Warner Tamerlane Publishing Corp. Used by permission. Allrights reserved.“Endangered Species (Tales from the Darkside)” by Ice Cube and Eric Sadler.Copyright 1990 WB Music Corp., Gangsta Boogie Music, Warner TamerlanePublishing Corp., Your Mother’s Music. All rights on behalf of Gangsta BoogieMusic administered by Warner Chapell Music (ASCAP). All rights on behalf ofYour Mother’s Music administered by Warner Tamerlane Publishing Corp. Usedby permission. All rights reserved.“The Product” by Ice Cube. Copyright 1990 Gangsta Boogie Music. All rightson behalf of Gangsta Boogie Music administered by Warner Chapell Music(ASCAP). Used by permission. All rights reserved.“How I Could Just Kill a Man.” Copyright 1993 BMG Songs, Inc. (ASCAP),Cypress Phunky Music, MCA Music Publishing, Budget Music, and PowerforceMusic. All rights for Powerforce Music and Budget Music administered byCareers-BMG Music Publishing, Inc. (BMI). All rights for Cypress Phunky

Music administered by BMG Songs, Inc. (ASCAP). Used by permission. Allrights reserved.“One Less Bitch” by T. Curry, L. Patterson, and A. Young. Copyright 1991Ruthless Attack Musik (ASCAP)/Sony Songs Inc. (BMI). Used by permission.All rights reserved.“Dress Code” by William Calhoun. Copyright 1991 337 Music, Base PipeMusic, Urban Music. Used by permission. All rights reserved.“Fuck My Daddy” by William Calhoun. Copyright 1991 337 Music, BasePipe Music. Used by permission. All rights reserved.“If You Don’t Work, U Don’t Eat” by William Calhoun. Copyright 1991 337Music, Base Pipe Music. Used by permission. All rights reserved.“Straight Up Nigga” by Ice T (Tracy Marrow). Copyright 1991 RhymeSyndicate Music (ASCAP). Used by permission. All rights reserved.“The Tower” by Ice T (Tracy Marrow). Copyright 1991 Rhyme SyndicateMusic (ASCAP). Used by permission. All rights reserved.Portions of chapters 1, 2, and 3 previously appeared in Robin D. G. Kelley, “‘WeAre Not What We Seem’: Re-thinking Black Working-Class Opposition in theJim Crow South,” Journal of American History 80, no. 1 (June 1993): 75-112.Used by permission. All rights reserved.Portions of chapter 4 previously appeared in Robin D. G. Kelley, “The BlackPoor and the Politics of Opposition in a New South City, 1929-1970,” in The“Underclass” Debate: Views from History, edited by Michael Katz (Princeton:Princeton University Press, 1993), 293-333. Used by permission. All rightsreserved.Portions of chapters 5 and 6 appeared in Robin D. G. Kelley, “Introduction,”African-Americans and the Spanish Civil War: “This Ain’t Ethiopia, But It’llDo,” edited by Danny Duncan Collum (New York: G. K. Hall, 1992), 5-57. Usedby permission of G. K. Hall Publishers and the Abraham Lincoln BrigadeArchives. Founded in 1979, the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives’ mission isto preserve historical materials relevant to the Spanish Civil War and toencourage broader public and scholarly understanding of the issues raised by

that conflict. The archive is located at Brandeis University, P.O. Box L11,Waltham, Mass., 02254.Chapter 7 previously appeared in a slightly revised form in Robin D. G. Kelley,“The Riddle of the Zoot: Malcolm Little and Black Cultural Politics DuringWorld War II,” in Joe Wood, ed., Malcolm X: In Our Own Image. Copyright Joe Wood. Reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Press, Incorporated.

To my two best friends, DIEDRA AND ELLEZA, who taught me more aboutresistance than I ever cared to know.

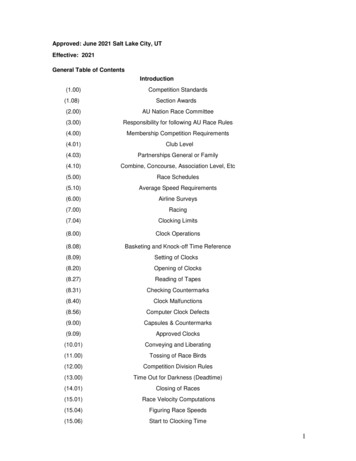

ContentsForeword by George LipsitzIntroduction: Writing Black Working-Class History from Way, Way BelowPART I. “WE WEAR THE MASK”: HIDDEN HISTORIES OFRESISTANCE1. Shiftless of the World Unite!2. “We Are Not What We Seem”: The Politics and Pleasures of Community3. Congested Terrain: Resistance on Public Transportation4. Birmingham’s Untouchables: The Black Poor in the Age of Civil RightsPART II. TO BE RED AND BLACK5. “Afric’s Sons With Banner Red”: African American Communists and the Politics of Culture, 191919346. “This Ain’t Ethiopia, But It’ll Do”: African Americans and the Spanish Civil WarPART III. REBELS WITHOUT A CAUSE?7. The Riddle of the Zoot: Malcolm Little and Black Cultural Politics During World War II8. Kickin’ Reality, Kickin’ Ballistics: “Gangsta Rap” and Postindustrial Los dex

ForewordIt is getting hotter all the time on the streets of America’s cities. Two years afterthe most destructive civil insurrection in U.S. history, many things have changedand few things have improved. Homeless men, women, and children congregateon downtown streets or seek shelter in abandoned warehouses and factories. Theseeming permanence of a low-wage, low-employment economy underminesmorale in the present and curtails hope for the future. Racial antagonisms sparkoutbursts of hate, hurt, and fear in high schools, in shopping centers, and on thestreets themselves. An entire generation of young people can see that they aresociety’s lowest priority: that they have been allocated the very worst ineducation, health care, transportation, and social services; that they are unwantedas workers, as students, as citizens, or sometimes, even as consumers.At the same time, there is a powerful and almost desperate desire for change. Inschools and on street corners, in medical clinics and community centers, inplaces of work and places of worship, the verdict is in on the disaster created inthis country by twenty years of neoconservative economics. Most people havesuffered terribly from the systematic dismantling of the human and social capitalof the United States that took place in the 1970s and 1980s, at the same time thattaxpayer dollars went to subsidize the spending sprees and speculative schemesof a wealthy few. In organized protest, but more in embryonic cultural coalitionscalling attention to the contradictions of our time, the contours of a new kind ofsocial movement are starting to emerge.Things are moving very fast, but in opposite directions—oscillating between therenewed racism and class stratification of the 1970s and 1980s, and theemergence of egalitarian, multi-issue, pan-ethnic antiracist coalitions. Thepresent and the future are up for grabs in a way that happens rarely in history.Our problem is that we don’t know enough—enough about how egalitariansocial change takes place, about how social movements start and how theysucceed, about how people find the will to struggle and the way to win when

they are facing forces far more powerful than themselves.Race Rebels arms us with what we need to know. It provides us with knowledge,with descriptions and analyses of what struggles for social change actuallyentail. Robin D. G. Kelley presents us with a picture of masses in motion, ofpeople as they actually are rather than as others wish them to be. He shows thatpolitical activism can never be a perfect, pure, or noncontradictory endeavor, thatit is messy and cannot be held in place by simple slogans suggested from theoutside. Instead, Kelley looks to history to learn how we can make sense out ofwhat is happening before our very eyes, how we can participate in a movementthat speaks from people rather than for them, and that allows people to openlyacknowledge the things that divide them even as they rally together for commongoals.In his discussion of black working-class opposition to racism and exploitation, offights over public space on Birmingham’s public buses, of the relationshipbetween the civil rights movement and the black poor, of the currents of blacknationalism nurtured within the Communist Party (USA), and his positivelybrilliant and inspiring readings of rap music and the zoot suit as icons ofopposition among aggrieved peoples, Kelley reads back to us the political truthof the lives we live. He shows how hard people have to fight to speak forthemselves, to find spaces for action, and to defend the gains they’ve won.Furthermore, Kelley frames these lively, insightful, and subtle studies within abroader analysis that delineates the bankruptcy of prevailing social sciencetheories about culture while pointing the way toward new ones. Race Rebels is abook for our time, a book that is on time, and a book that understands it is pasttime to face up to our responsibilities and to make the most of our opportunities.—GEORGE LIPSITZDepartment of Ethnic StudiesUniversity of California at San Diego

IntroductionWriting Black Working-Class History from Way, Way BelowAgainst this monster, people all over the world, and particularly ordinaryworking people in factories, mines, fields, and offices, are rebelling every day inways of their own invention. Sometimes their struggles are on a small personalscale . Always the aim is to regain control over their own conditions of life andtheir relations with one another. Their strivings have few chroniclers. Theythemselves are constantly attempting various forms of organization, uncertain ofwhere the struggle is going to end.—C.L.R. JAMES, GRACE C. LEE, AND PIERRE CHAULIEU, FacingReality1“McDonald’s is a Happy Place!”I really believed that slogan when I began working there in 1978. For many of usemployed at the central Pasadena franchise, Mickey D’s actually meant food,folks, and fun, though our main objective was funds. Don’t get me wrong; thework was tiring and the polyester uniforms unbearable. The swing managers,who made slightly more than the rank-and-file, were constantly on our ass tomove fast and smile more frequently. The customers treated us as if we werestupid, probably because 90 percent of the employees at our franchise wereAfrican Americans or Chicanos from poor families. But we found inventiveways to compensate. Like virtually all of my fellow workers, I liberatedMcDonaldland cookies by the boxful, volunteered to clean “lots and lobbies” inorder to talk to my friends, and accidentally cooked too many Quarter Poundersand apple pies near closing time, knowing fully well that we could take homewhatever was left over. Sometimes we (mis)used the available technology to ouradvantage. Back in our day, the shakes did not come ready mixed. We had topour the frozen shake mix from the shake machine into a paper cup, add flavoredsyrup, and place it on an electric blender for a couple of minutes. If it was not

attached correctly, the mixer blade would cut the sides of the cup and cause adisaster. While these mishaps slowed us down and created a mess to clean up,anyone with an extra cup handy got a little shake out of it. Because we wereunderpaid and overworked, we accepted consumption as just compensation—though in hindsight eating Big Macs and fries to make up for low wages andmistreatment was probably closer to self-flagellation.That we were part of the “working class” engaged in workplace struggles nevercrossed our minds, in part because the battles that were dear to most of us andthe strategies we adopted fell outside the parameters of what most people thinkof as traditional “labor disputes.” I’ve never known anyone at our McDonald’s toargue about wages; rather, some of us occasionally asked our friends to punchour time cards before we arrived, especially if we were running late. And no oneto my knowledge demanded that management extend our break; we simplyoperated on “CP” (colored people’s) time, turning fifteen minutes into twentyfive. What we fought over were more important things like what radio station toplay. The owner and some of the managers felt bound to easy listening; weturned to stations like K-DAY on AM or KJLH and K-ACE on the FM dial sowe could rock to the funky sounds of Rick James, Parliament, Heatwave, TheOhio Players, and—yes—Michael Jackson. Hair was perhaps the most contestedbattle ground. Those of us without closely cropped cuts were expected to wearhairnets, and we were simply not having it. Of course, the kids who identifiedwith the black and Chicano gangs of the late seventies had no problem with thisrule since they wore hairnets all the time. But to net one’s gheri curl, a lingeringAfro, a freshly permed doo was outrageous. We fought those battles withamazing tenacity—and won most of the time. We even attempted to alter ourugly uniforms by opening buttons, wearing our hats tilted to the side, rolling upour sleeves a certain way, or adding a variety of different accessories.Nothing was sacred, not even the labor process. We undoubtedly had our shareof slowdowns and deliberate acts of carelessness, but what I remember most wasthe way many of us stylized our work. We ignored the films and manuals andturned work into performance. Women on the cash register maneuveredeffortlessly with long, carefully manicured nails and four finger rings. Tossingtrash became an opportunity to try out our best Dr. J moves. The brothers whoworked the grill (it was only brothers from what I recall) were far moreconcerned with looking cool than ensuring an equal distribution of reconstitutedonions on each all-beef patty. Just imagine a young black male “gangsta limpin’”between the toaster and the grill, brandishing a spatula like a walking stick or a

microphone. And while all of this was going on, folks were signifying on oneanother, talking loudly about each other’s mommas, daddys, boyfriends,girlfriends, automobiles (or lack thereof), breath, skin color, uniforms; onoccasion describing in hilarious detail the peculiarities of customers standing onthe other side of the counter. Such chatter often drew in the customers, whofound themselves entertained or offended—or both—by our verbal circus andcollective dialogues.2The employees at the central Pasadena McDonald’s were constantly inventingnew ways to rebel, ways rooted in our own peculiar circumstances. And wenever knew where the struggle would end; indeed, I doubt any of us thought wewere part of a movement that even had an end other than punching out a timecard (though I do think the “Taylorizing” of McDonald’s, the introduction ofnew technology to make service simpler and more efficient, has a lot to do withmanagement’s struggle to minimize these acts of resistance and recreation).3 Butwhat we fought for is a crucial part of the overall story; the terrain was oftencultural, centering on identity, dignity, and fun. We tried to turn work intopleasure, to turn our bodies into instruments of pleasure. Generational andcultural specificity had a good deal to do with our unique forms of resistance,but a lot of our actions were linked directly to the labor process, genderconventions, and our class status.Like most working people throughout the world, my fellow employees atMickey D’s were neither total victims of routinization, exploitation, sexism, andracism, nor were they “rational” economic beings driven by the most baseutilitarian concerns. Their lives and struggles were so much more complicated. Ifwe are to make meaning of these kinds of actions rather than dismiss them asmanifestations of immaturity, false consciousness, or primitive rebellion, wemust begin to dig beneath the surface of trade union pronouncements, politicalinstitutions, and organized social movements, deep into the daily lives, cultures,and communities which make the working classes so much more than peoplewho work. We have to step into the complicated maze of experience that renders“ordinary” folks so extraordinarily multifaceted, diverse, and complicated. Mostimportantly, we need to break away from traditional notions of politics. We mustnot only redefine what is “political” but question a lot of common ideas aboutwhat are “authentic” movements and strategies of resistance. By “authentic” Imean the assumption that only certain organizations and ideologies can trulyrepresent particular group interests (e.g., workers’ struggles must be locatedwithin labor organizations, or African American concerns are most clearly

articulated in so-called “mainstream” civil rights organizations such as theNAACP or the Urban League). Such an approach not only disregards diversityand conflict within groups, but it presumes that the only struggles that count takeplace through institutions.If we are going to write a history of black working-class resistance, where do weplace the vast majority of people who did not belong to either “working-class”organizations or black political movements? A lot of black working peoplestruggled and survived without direct links to the kinds of organizations thatdominate historical accounts of African American or U.S. working-classresistance. The so-called margins of struggle, whether it is the unorganized, oftenspontaneous battles with authority or social movements thought to be inauthenticor unrepresentative of the “community’s interests,” are really a fundamental partof the larger story waiting to be told.Race Rebels begins to recover and explore aspects of black working-class lifeand politics that have been relegated to the margins. By focusing on the dailylives of African American working people, strategies of resistance and survival,expressive cultures, and their involvement in radical political movements, thisbook attempts to chronicle the inventive and diverse struggles waged by blackworkers during the twentieth century and to understand what they mean forrethinking the way we construct the political, social, and cultural history of theUnited States. I chose the title Race Rebels because this book looks at forms ofresistance—organized and unorganized—that have remained outside of (andeven critical of) what we’ve come to understand as the key figures andinstitutions in African American politics. The historical actors I write about areliterally race rebels and thus have been largely ignored by chroniclers of blackpolitics and labor activism. Secondly, the title points to the centrality of race inthe minds and experiences of African Americans. Race, particularly a sense of“blackness,” not only figures prominently in the collective identities of blackworking people but substantially shapes the entire nation’s conceptions of classand gender. Part of what Race Rebels explores is the extent to which blackworking people struggled to maintain and define a sense of racial identity andsolidarity.Some of the questions Race Rebels takes up have their roots in works by anolder generation of radical scholars who chose to study slavery and its demisewhen fascism was on the rise in Europe and the future of colonialism wasuncertain. The two most influential books in this respect were written nearly

three decades before E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class—namely, W.E.B. DuBois’s Black Reconstruction (1935) and C.L.R. James’sstudy of the Haitian Revolution titled Black Jacobins (1938). These majestichistories of revolution, resistance, and the making of new working classes out ofthe destruction of slavery anticipated the “new” social historians’ efforts to write“history from below.” They also contributed enormously to revising the historyof Western revolutions by placing race, culture, and the agency of Africanpeople—the slaves and ex-slaves—at the center of the story. Neither authorviewed the newly created black proletariat as merely passive products ofeconomic exploitation and dislocation. In DuBois’s account freedpeople are onthe move, undermining slavery at every halting step. The men and women whofought to reconstruct the South were more than servants and cotton pickers; theywere Negroes with a capital N, they belonged to families and churches, and theybrought with them a powerful millenarian vision of fairness and equality. Andthe white poor who supported efforts to stop them, the folks whose mostvaluable possession was probably their skin, put the noose around their ownneck in exchange for membership in the white race. Black Reconstruction maystill be the most powerful reminder of how fundamental race is forunderstanding American culture and politics. For C.L.R. James the slaves’memories of Africa, the world they created in the quarters bordering the canefields, the social meaning ascribed to skin color, the cultural and religiousconflicts within African-descended communities, were as critical to creating andshaping the Revolution as were backbreaking labor and the lash.4The “new labor” or “new social historians,” who set out to write “history frombelow” in the early to mid-1960s, traveled even further down the road opened upby their predecessors. Unlike DuBois and James, whose work on black “labor”entered the scholarly world either quietly or amid vehement opposition, this newgeneration of historians caused a revolution. The story of its origins is sofamiliar that it may one day be added to the New Testament. The late E. P.Thompson was the Moses of it all, along with his British ex-Communistcomrades and fellow travelers like Eric Hobsbawm and Africanists like TerrenceRanger; across the Channel were prophets like George Rudé, and across theAtlantic were disciples like Herbert Gutman, David Montgomery, EugeneGenovese, and so on.5 They differed in time, place, and subject matter, but theyall shared the radical belief that one could, indeed, write history “from below.”Of course, there were those critics who felt the new genre failed to take on thestate or ignored political economy. And for all of its radical moorings, “historyfrom below” started out very manly and very white (or at least Euro-ethnic),

though that changed somewhat with the emergence of women’s and ethnicstudies.Yet, as old as the “new” labor history is, “history from below” in its heyday hada very small impact on the study of African Americans.6 Certainly, there arethose who might argue that all black history is “from below,” so to speak, sinceAfrican Americans are primarily a working-class population. This view has itsproblems, however. Aside from the fact that every racial or ethnic group in theUnited States was primarily working class, it denies or minimizes diversity andconflict within African American communities. Unable to see a world that leftfew written records, many scholars concerned with studying “race relations”folded the black working class into a very limited and at times monolithicdefinition of the “black community.” By overlooking or playing down class andgender differences, mainstream middle-class male leaders have too often beenregarded as, in historian Nell Painter’s words, “representative colored men.”7The chapters in part I not only question whether a handful of “representativeNegroes” can speak for the mass of working-class African Americans, but alsosuggest that some of the most dynamic struggles take place outside—indeed,sometimes in spite of—established organizations and institutions. All fourchapters explore the political significance of everyday forms of resistance atwork and in public space, the pleasures and politics of culture, and communityinstitutions that are usually not defined as “working-class” organizations. Inother words, I sought to dig a little deeper, beneath “below,” to those workerswhose record of resistance and survival is far more elusive. I’m referring here toevasive, day-to-day strategies: from footdragging to sabotage, theft at theworkplace to absenteeism, cursing to graffiti.These chapters also explore the double-edged sword of race in the South, whichis why I called part I “We Wear the Mask” from Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poemof the same title. The mask of “grins and lies” enhanced black working people’sinvisibility and enabled them to wage a kind of underground “guerrilla” battlewith their employers, the police, and other representatives of the status quo.Although the South certainly had its share of militant African American andinterracial movements, and the status quo was sufficiently afraid of rebellion toexpend a tremendous amount of resources on keeping the peace and surveillingblack communities, the mask worked precisely because most Southern whitesaccepted their own racial mythology; they believed that “darkies” were happyand content, and that any open, collective acts of defiance were probably

inspired from the outside. On the other hand, the “mask” exacted a price fromblack folks as well. The inner pain generated by having to choke back one’sfeelings in the face of racism could create tensions. Writer Gloria Wade-Gayles,who grew up in a Memphis housing project and came of age on the eve of thecivil rights movement, beautifully captured this dilemma: “As teenagers, manyof us were caught between our anger at white people and our respect for ourblack elders; between a need to vent our rage in the light of day and a desire toremain alive; and between two images of our people: one for downtown and theother for ourselves.”8 As I suggest in my discussion of black resistance duringWorld War II and during the civil rights movement, the “mask” was no longerviable; evasive strategies continued, to be sure, but often with a militant face.No matter what we might think about the “grins and lies,” the evasive tactics, thetiny acts of rebellion and survival, the reality is that most black working-classresistance has remained unorganized, clandestine, and evasive. The drivingquestions that run through this book include: how do African American workingpeople struggle and survive outside of established organizations or organizedsocial movements? What impact do these daily conflicts and hidden concernshave on movements that purport to speak for the dispossessed? Can we call thispolitics?“History from below” clearly pushed me to explore the politics of the everyday.The approach I take is deeply influenced by scholars who work on South Asia,especially political anthropologist James C. Scott. Scott maintains that, despiteappearances of consent, oppressed groups challenge those in power byconstructing a “hidden transcript,” a dissident political culture that manifestsitself in daily conversations, folklore, jokes, songs, and other cultural practices.One also finds the hidden transcript emerging “onstage” in spaces controlled bythe powerful, though almost always in disguised forms. The veiled social andcultural worlds of oppressed people frequently surface in everyday forms ofresistance—theft, footdragging, the destruction of property—or, more rarely, inopen attacks

administered by Warner Chapell Music (ASCAP). All rights on behalf of Your . (New York: G. K. Hall, 1992), 5-57. Used . It is getting hotter all the time on the streets of America's cities. Two years after the most destructive civil insurrection in U.S. history, many things have changed .