Transcription

THE BLUE RIDGE ACADEMIC HEALTH GROUPFinancially Sustaining theAcademic EnterpriseSPRING 2022 Report 25

Members and Participants(June 2021 virtual meeting)MEETING CO-CHAIRSJonathan S. Lewin, MDExecutive VP for Health Affairs, Emory University; ExecutiveDirector, Woodruff Health Sciences Center; President, CEO,and Board Chairman, Emory HealthcareJeffrey R. Balser, MD, PhDPresident and CEO, Vanderbilt University Medical Center;Dean, Vanderbilt University School of MedicineOT HE R M E M B E R SS. Wright Caughman, MDProfessor, Emory School of Medicine and Rollins School ofPublic Health, Emory University; Executive VP for HealthAffairs Emeritus, Emory UniversityMichael V. Drake, MDPresident, University of CaliforniaJulie A. Freischlag, MDDean, Wake Forest University School of Medicine; CEO,Wake Forest Baptist Medical CenterMichael M.E. Johns, MDProfessor, Emory School of Medicine and Rollins School ofPublic Health, Emory University; Executive VP for HealthAffairs Emeritus, Emory University; President, CEO, andBoard Chairman Emeritus, Emory HealthcareLloyd B. Minor, MDDean, Stanford University School of MedicineMary D. Naylor, PhDMarian S. Ware Professor in Gerontology; Director,NewCourtland Center for Transitions and Health,University of Pennsylvania School of NursingDaniel K. Podolsky, MDPresident, University of Texas Southwestern Medical CenterKenneth S. Polonsky, MDExecutive VP for Medical Affairs; Dean, Biological SciencesDivision and School of Medicine, University of ChicagoClaire Pomeroy, MD, MBAPresident, Albert and Mary Lasker FoundationPaul B. Rothman, MDDean of Medical Faculty, Johns Hopkins University School ofMedicine; Vice President for Medicine, Johns HopkinsUniversity; CEO, Johns Hopkins MedicineMarschall S. Runge, MD, PhDExecutive VP for Medical Affairs, University of MichiganFred Sanfilippo, MD, PhDDirector, Healthcare Innovation Program, Emory UniversityRichard P. Shannon, MDChief Quality Officer, Duke HealthDavid Skorton, MDPresident and CEO, Association of American MedicalColleges (AAMC)Irene M. ThompsonVice Chair, AMC Networks Board of Managers, Vizient, Inc.William N. Kelley, MDProfessor of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine,University of Pennsylvania; Trustee Emeritus, EmoryUniversityDarrell G. Kirch, MDPresident Emeritus, Association of American MedicalColleges (AAMC)Elizabeth G. Nabel, MDExecutive Vice President for Strategy, ModeX TherapeuticsArthur H. Rubenstein, MBBChProfessor of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine,University of PennsylvaniaJohn D. Stobo, MDFormer Executive VP, UC Health, University of CaliforniaBruce C. Vladeck, PhDFormer CMS Administrator and Health Policy AdviserFEATURED PRESENTERSPaul CastilloChief Financial Officer, University of Michigan Health SystemJoanne M. Conroy, MDPresident and CEO, Dartmouth-Hitchcock and DartmouthHitchcock HealthTerry L. Hales Jr.Vice President, Academic Administration and Operations,Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist; Executive Vice Dean,Wake Forest School of MedicineHeather HambyExecutive Associate Dean and Chief Business Officer, EmorySchool of Medicine; Senior Vice President for AcademicIntegration, Emory Healthcare; Associate Vice President forHealth Center Integration, Woodruff Health Sciences CenterK. Craig Kent, MDExecutive Vice President for Health Affairs, University ofVirginia; Chief Executive Officer, UVA HealthCecelia MooreChief Financial Officer and Treasurer, Vanderbilt UniversityMedical CenterSteven D. Shapiro, MDSenior Vice President for Health Affairs, University ofSouthern CaliforniaFACI LI TATORS AND AUTHORSSteve LevinDirector, The Chartis GroupAlexandra SchummPrincipal and VP for Research, The Chartis GroupMichael TsiaPrincipal, The Chartis GroupGUESTJohn RiceFormer Vice Chairman, General Electric Company (retired);Trustee, Emory University Board of Trustees; Chair, WoodruffHealth Sciences Center Committee of the Emory UniversityBoard of TrusteesS TAFFS E NI O R M E M B E R SAnita BrayProject Coordinator, Woodruff Health Sciences Center,Emory UniversityDon E. Detmer, MD, MAProfessor of Medical Education, University of VirginiaJudi FyolaExecutive Assistant, Woodruff Health Sciences Center,Emory UniversityWilliam R. Brody, MD, PhDProfessor Emeritus, Salk Institute for Biological StudiesMichael A. Geheb, MDSenior Consulting Director, IBM Watson Health; Board ofDirectors, Wayne State University Physician GroupGary L. TealVice President, Woodruff Health Sciences CenterEmory University

Mission: TheBlue Ridge Academic Health Group seeksto take a societal view of health and health care needsand to identify recommendations for academic health centers(AHCs) to help create greater value for society.The Blue Ridge Group also recommends public policiesto enable AHCs to accomplish these ends.ContentsReport 25.Financially Sustaining the Academic EnterpriseIntroduction: The Economics of the Academic Health Center (AHC) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2I. Discussion and Commentary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5II. Conclusions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Previous Blue Ridge Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13About the Blue Ridge Academic Health Group . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Reproductions of this document may be made with written permission of Emory University’s Woodruff Health Sciences Center by contactingAnita Bray, Emory School of Medicine, James B. Williams Medical Education Building, 100 Woodruff Circle, Suite A367, Atlanta, GA, 30322.Phone: 404-712-3510. Email: abray@emory.edu.Recommendations and opinions expressed in this report represent those of the Blue Ridge Academic Health Group and are not official positions of Emory University. This report is not intended to be relied on as a substitute for specific legal and business advice.Copyright 2022 by Emory University.22-EVPHA-EVPHA-0053

The Economics ofthe Academic Health Center (AHC)Introduction:Overview of Academic HealthCenter Funding ModelAcademic Health Centers (AHCs) are the backbone of health and health care innovation in theUnited States (US), in addition to their fundamental mission of educating the next generationof clinicians and researchers. Many of the criticaladvances in medicine have originated in AHCs,including discoveries that led to mRNA vaccines,radiation therapy, statins, human organ transplantsurgery, drugs to treat HIV/AIDS, and cardiacdefibrillators. These monumental innovationsand discoveries require substantial and sustainedresearch and innovation, core differentiating components of AHCs that embody the passion andmission of academic institutions.However, the AHC research enterprise alwaysrequires financial support from other sources,even when faculty investigators receive fundingfrom the National Institutes of Health (NIH),private funding from corporations, and philanthropy. This funding gap necessitates investmentof clinical margin into the academic enterpriseto cover the financial shortfall, and today thatsupport is estimated at more than 20 billionannually. Adding education further escalates theamount. To produce this margin—and to haveenough left over to reinvest in the clinical enter2prise itself—the AHC clinical enterprise mustyield exceptional financial productivity, sincegovernment reimbursement (Medicare, Medicaid)usually falls short of cost. Fortunately, investingclinical margin in the academic enterprise yieldsreturns for both: By supporting primary research activities,growth in external grant and contract fundingas well as downstream philanthropy and technology transfer are catalyzed. Investments in research improve the stature andvisibility of AHCs as the providers of the mostadvanced and innovative health care, whichattracts clinicians of national stature and helpsgrow physician referrals. Investments in humansubjects research programs (clinical trials) alsohelp attract patients to AHCs. Increased patient volume drives growth in clinical revenue, which can then be reinvested intoresearch and/or education. This harmonious cycle—referred to as the“virtuous circle” of academic medicine (Figure 1)—results in AHCs in most communities being viewed as the preferred providerfor complex care, the locus of innovation and“bleeding edge” medicine for the world, and theclassroom for the next generation of physicians,scientists, and other health professionals.

Threats to the Virtuous CircleIn recent years, the virtuous circle has been fueledby significant clinical enterprise growth, whichhas enabled continued investment despite flat ordeclining per capita reimbursement from government and private payors relative to inflation.However, AHC investment of clinical surplusesto support academic activities is under stress asthe nation, including both payors and patients,seek to limit the growth of health care spending.Several challenges and headwinds are putting thatfunding under increased pressure, threateningthe virtuous circle’s foundation and the overallfinancial sustainability of AHCs. The challengesand headwinds include:1. Increased costs from labor workforce shortages: All health systems are under tremendouscost pressure as clinical and administrativestaff shortages, driven partly by the COVID-19 pandemic, have reduced clinicalcapacity and increased labor costs throughFIGURE 1 Academicwage increases and more widespread use ofpremium-pay temporary labor. The Bureau ofLabor Statistics reported in November 2021that hospitals’ labor costs increased 8 percentper patient day since 2017.12. Payor mix shift: As the population ages, largenumbers of patients with private insuranceconvert to Medicare—currently about 3,500net enrollees every day.2 This results in anoverall payor mix shift across the health careindustry. Government reimbursement ratesare typically well below the cost of care andare often less than half what private insurerspay providers. In addition, annual increasesare well below inflation, making it increasinglydifficult to cover increasing operating costsand make needed investments in equipmentand facilities.3. Lower commercial rate increases: Providersare seeing lower contracted rate increases asMedicine’s Virtuous CircleInvestment of clinicalpractice income into theacademic enterprise . . . . . leads toincreased patientreferrals, clinicalfaculty quality, andoverall successACADEMICMEDICINE’SVIRTUOUS CIRCLE. . . drives improvedstature and visibilityfor the clinical andresearch enterprises. . . fuels increasedresearchproductivity,technology transfer,leverage to externalsupportSOURCE: “The Relationship betweenthe University of Pittsburgh Schoolof Medicine and the University ofPittsburgh Medical Center: A Profilein Synergy,” Academic Medicine83(9), September 2008.3

commercial payors attempt to deliver moreaffordable health care coverage to employersand employees. In addition, some insurers aredirecting patients away from AHCs towardlower cost community sites of care for outpatient services in an effort to reduce healthcare costs.4. Disproportionate share of uninsured andunderinsured patients: AHCs provide adisproportionate amount of care for the nation’s uninsured and underinsured. As such,they are particularly vulnerable to reductionsin programs designed to support disproportionate share providers, such as proposed cutsand downscaling efforts to the 340b programin recent years as well as noncompliance withthis program by six pharmaceutical manufacturers in 2021.35. Lack of other consistent and reliable funding: Other funding sources can be unpredictable. For example, philanthropy can fluctuatesignificantly from year to year and technologytransfer revenues are highly variable and havea finite timespan.The challenges related to COVID-19 over thepast two years have further exposed the vulnerability of the current academic funding modeland exacerbated the headwinds described above.AHCs provided a critical backstop in manycommunities for COVID-19 care when beds andprovider supply were limited, and despite CARESAct funding, AHCs have experienced sustainedlower operating margins than not-for-profit andfor-profit systems, per a recent Moody’s Investor Services report.4 In addition, provider mentalhealth and wellness—already strained prepandemic, as described in a previous Blue RidgeAcademic Health Group (BRAHG) report5—wasfurther degraded through the pandemic and iscontributing to workforce shortages and increasedcosts. Finally, the drop in state revenue collectionsdue to the economic slowdown from COVID-19has stretched state budgets. Fifteen states havereduced their health care budgets in the last twoyears,6 which negatively impacts Medicaid fund4ing and/or limits other state-sponsored grantsonce recent federal relief funds taper off.Increasing Academic Funding NeedsResearch enterprise trends necessitate increasedinvestment relative to years past despite pressureon clinical margins, reducing the available funds.The research funding shortfall at AHCs typicallyranges from 25 to 50 percent of the institution’stotal extramural research funding, and the gap iswidening. This shortfall is driven by indirect costrecovery rates that do not consistently cover theactual cost of space and research administration,support junior investigator requirements beforethey can successfully compete for grant support,and NIH salary caps that continue to fall furtherbelow actual salary costs, exacerbated in part bythe increasing cost of attracting top-tier researchfaculty. As a result, increased investment isneeded just to maintain current levels of researchat most AHCs. Ever higher levels of investmentare required to grow the research enterprise, asthere is no evidence that economies of scale canbe achieved as the research enterprise expands.Most AHCs aspire to grow their research enterprise, particularly at a time when NIH fundinghas begun increasing after more than a decadeof flat funding, which represented a decline inreal dollars.Medical education also requires increasing investment. There are a growing number ofinternally funded graduate medical education(GME) positions due to antiquated caps—in 2018,70 percent of hospitals were over the direct and/or indirect cap on Medicare-funded residents.The gap is increasing despite growth in medicalstudent class size and in the number of medical schools in an effort to help expand physician supply.7 Undergraduate medical education(UME) curriculum changes are deemphasizingthe relatively efficient lecture model and shiftingmore of the educational experience toward teambased learning models— a more costly approachto education. Tuition rarely covers the full cost ofUME, causing some medical schools to increaseclass size in an attempt to create economies ofscale. There is also an increasing expectation forreduced or no tuition to compete for top students

and to make medical education more affordableacross socioeconomic groups to increase diversity,further adding to rising medical education costsfor AHCs.The Challenge Facing AHCsThe hurdles highlighted above require AHCleaders to consider new and evolving strategiesto maintain and grow the academic enterprise.Rather than explore the full range of potentialanswers to this complex and layered question, thisreport explores three targeted areas that may wellhave a disproportionate impact: How are AHCs using funds flow models andeconomic incentives to help improve financialperformance to reduce the research fundingshortfall and to increase the funds availableto support the research enterprise? Are theseapproaches effective? What are the key successfactors? Department chair packages often requiresignificant investment, particularly in the largest departments. Are sizeable chair packagesrequired and sustainable? What other fundingand investment approaches should be considered? How often are chair term limits or othertechniques used, and how do they impact funding needs and approaches? Is substantial expansion of clinical enterprisescale effective (or required) to secure theclinical margins required to help support theacademic enterprise? If so, what strategies areviable and what are the risks and benefits?DISCUSSION AND COMMENTARYSupporting the Sustainability of the VirtuousCircle: Re-examining Funds Flow ModelsAs highlighted earlier, substantial investmentof clinical margin is required to support everyAHC’s academic enterprise. In many AHCs, thisinvestment occurs via a complex and opaqueweb of funds that flow across the health system,faculty practice plan, and school of medicine. Forexample, the health system may offer the school ofmedicine an academic investment fund transfer tosupport academic activities, and the school maythen distribute it among departments to supportthe research efforts of individual faculty members.Thousands of similar funding line items oftenexist in an AHC which can create a funding webso layered and transparent that the amounts, purpose, or time period of funding transfers may notbe fully clear to the recipients and/or sender. Inaddition, as AHCs have grown by adding community physicians, hospitals, and other care deliverysites, the degree of financial support providedmay also vary across these operating units, withthe core teaching hospital typically providing themost financial support. These variable levels ofsupport sometimes impede efforts to operate as anintegrated delivery system attempting to optimizeoverall enterprise performance.It is not uncommon for the details of fundsflow models to be opaque to senior leaders atan AHC, as models are often complex, vary bydepartment, and can include numerous exceptions and “side deals” cobbled together over manyyears. However, it is imperative that AHC leaders,including all department chairs, have a solidunderstanding of the funds flow model in placeto understand what level of support is affordableand to ensure these resources are being used appropriately and effectively so that the model canbe altered and improved where needed. This approach requires transparency between the clinicaland academic enterprises, as well as clear incomeand cost allocation methodologies within themedical school.Effective funds flow models align incentivesand employ them as powerful motivators to helpimprove performance. An approach at certainBRAHG institutions modifies the expectations forclinical departments and chairs by establishingpay-for-performance metrics and faculty compensation incentives on factors the departmentcan more directly impact: clinical productivityand faculty performance on measures of quality,patient service, and patient access rather than onindividual department clinical margins. Clinicaldivisions and departments receive their annualclinical incentive based on their scores on thisbalanced report card. This approach removesprevious distortions that may have allowed for underperformance, such as lucrative payor contractsfor select services, which made some departmentslook profitable despite faculty members being5

below median productivity benchmarks. Underthe new model, clinical departments and theirdivisions closely manage their faculty to performwell on key metrics, not only for financial reasonsbut also for reasons of reputation, as scores areregularly published for all leaders to see. Measuring the performance of each division and department using the same balanced scorecard allowsthe AHC to align behavior, ensure consistency,and maximize impact. This model also reducesthe need for each clinical department to negotiatefor financial support from the health system toreach breakeven or better financial performance.However, the movement to focus chairs, faculty,and other leaders on overall clinical enterpriseprofitability, rather than departments as the primary profit center, represents a significant culturalchange, especially for those departments thatremained profitable without significant financialsupport.One lesson learned is for the funds flow incentive to be more directly tied to individual actionsto spur meaningful behavior change across alllayers within the organization. While macrolevel incentives (e.g., AHCs that share a portionof health system net operating margin with themedical school) can help motivate and providecentral funding for the academic enterprise, theymay be less likely to motivate department chairsand faculty to function differently. One AHC atthe BRAHG meeting described its clinical margin-sharing methodology, whereby a portion ofthe clinical margin is distributed based on healthsystem profits and the amount of profit shares individual departments previously purchased. Somedepartment chairs have recognized the healthsystem can still generate a healthy clinical marginand distribute a satisfying profit share, even iftheir individual department is not as productiveor contributing to overall health system marginimprovement. The profit share in this instancemay enable some departments to be complacentabout optimizing clinical productivity. MostAHCs are evolving away from an operating modelin which each medical school clinical departmentfunctions with complete autonomy to one with agreater focus on both departmental and collectiveperformance. As AHCs transition to more team6based funds flow models, it is important to ensureincentives are aligned across various leadershiplevels, from division leaders, to departmentchairs, to school of medicine, practice plan andhealth system leaders.Another key characteristic of effective fundsflow models is appropriate sizing of the researchenterprise investment relative to what the AHCcan afford from clinical margins based on scaleand profitability. One AHC described its formulaic approach to defining how much they can affordto invest in financial support for their researchenterprise. The AHC sets the annual growthof its research investment with clinical dollarsto the same percentage growth rate as its clinical operating margin. To minimize year-to-yearvariation due to large changes in clinical enterprise profitability, the institution sets a ceiling forannual research enterprise investment growth of10 percent and a floor at the federal research costinflation benchmark (BRDPI). All research budgetfunding increase requests must fit within the resulting growth rate. This approach allows for morepredictable research investment and also moredirectly ties research funding growth to clinicalenterprise growth and margins, further incentivizing department chairs and research leaders tostrive for high performance of clinical faculty andthe overall clinical enterprise.While there are many more characteristics ofhighly effective funds flow models to discuss, thefew highlighted above show the importance ofdata transparency and use of incentives at appropriate levels to drive individual and team behavioras well as the criticality of sizing the researchenterprise relative to clinical profitability.Recognizing the Importance of FacultyRecruitment and Ensuring a SustainableModel for the FutureThe importance of having chairs who can buildand lead successful departments cannot beoverstated. Strong department chairs attract othertalented faculty researchers and clinicians, drawexternal research funding, and elevate the AHC’sbrand and reputation through the chairs’ and theirdepartments’ research contributions and clinical capabilities. This in turn helps grow patient

referrals and corresponding clinical revenue andhelps attract the best and brightest residents andfellows, further bolstering an AHC’s clinical andresearch enterprises.Department chair recruitment packages (alsoknown as “chair packages”) are costly and increasingly difficult to afford at many medical schoolsand AHCs wrestling with financial headwinds.However, the cost of these packages is unlikely tobudge, and it is highly unlikely that the practiceof granting chair packages will decline in the nearfuture. Candidates know their success is highlydependent on resources secured before they accept an offer (and therefore they are willing tonegotiate strongly), and AHCs must compete tosecure the best talent.However, some practices around chairpackages are changing to alleviate or spread thefinancial burden over time and to ensure thesefunds are spent appropriately. Many AHCs havedeveloped multiyear financial forecasts, which include expected expenditures on current academicenterprise commitments and, more important,forecasts of the expected costs for future department chair recruits. Increasingly, these projectionsdictate the maximum expenditure or guardrailregarding the funds available for each recruit.The projected cost of chair packages is based on areview of the future needs in departments whererecruitment is expected and the estimated costsof addressing those needs. This approach demonstrates an increasing intention by select AHCsto first consider what the enterprise needs from adepartment, then the appropriate chair packagefunding required to meet those strategic objectives. After determining what funding is needed,the AHC may search for a chair candidate who fitswithin (while helping adjust) that vision, ratherthan allow a chair candidate to have free reign toset a vision and dictate the funding needed.Once a package is granted and the chair accepts the offer, at some institutions committedfunds are managed centrally and distributed overtime, based on research and academic activityprojects and needs. Chairs must still provide anannual justification for their proposed investmentsbefore funds are made available within the limitsof the previously agreed-upon package. This mod-el assures oversight of spending, aligns institutional priorities with those of chairs and departments,and may spread the spending of committed fundsover a longer time period, given the realistic challenges chairs often experience with new facultyrecruiting (a five-year package is sometimes spentover seven to eight years or more).While some AHCs now provide renewedpackages after the initial package is fully spent toprovide additional funding for departmental investments and reduce chair turnover, this practicecan create additional expenditures and contributeto AHC and medical school economic challenges.Some recruitments now include non-monetary chair package components, such as providing leadership training or support, often gearedto help nontraditional candidates acclimate toand succeed in their new leadership roles. Thisapproach can help expand the pool of candidatesand increase diversity among chairs.Pursuing Long-term Sustainability throughScale: Exploring the Opportunities, Risks, andNuances in Growing a Larger Clinical Enterprise to Support the Overall AHCGrowing the scale of the clinical enterprise has thepotential to support an AHC’s long-term financialsustainability. In the Blue Ridge Academic HealthGroup’s 2017 report, The Academic Health Center:Delivery System Design in the Changing HealthCare Ecosystem—Sizing the Clinical Enterprise toSupport the Academic Mission,8 we outlined therationale for clinical scale growth through the lensof providing financial and other support for theacademic mission, including: Maintaining sufficient patient volumes for education programs. Sustaining the scope and diversity of patientsneeded for educational and clinical researchprograms. Maintaining sufficient revenue and marketpresence in many cases to support the crosssubsidy or academic transfer funds required tofund academic programs.Because of academic needs and financialshortfalls, most AHCs spend 5–10 percent ofclinical enterprise revenues to support the faculty,of which 1.5–2.5 percent of net revenues are for7

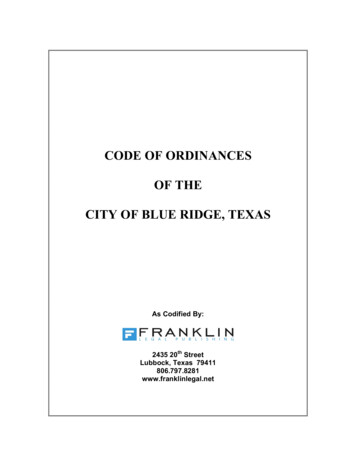

explicit academic support. Many AHCs also provide additional funding to clinical departments,marginally increasing the overall percent of netpatient revenue supporting the academic enterprise. AHC academic costs are growing and mustcontinue to grow to meet and excel in education,training, and research demands and opportunities. As long as AHC clinical operating marginsare maintained, strategic growth of the AHCclinical enterprise should result in growth in netrevenue available for research and education with-FIGURE 2 Largeout increasing the overall percentage of revenuessupporting the academic mission.Many AHC clinical enterprises have beensuccessful in growing their scale and revenuessubstantially over the past decade (see Figure 2).They have achieved their market-leading positions by differentiating their clinical capabilities,increasing clinical capacity by expansion of boththeir faculty and community provider workforce,and by aggressively managing clinical effortand productivity.AHC Hospital Operating Revenue Growth2010 OP REVENUE2019 OP REVENUE(2019 dollars, millions)(millions)LARGE AHCS - HOSPITAL OPERATINGREVENUE SIZE COMPARISON, 2019 1,599 4,959Yale 1,251 2,934UW Medicine 3,065 7,051Stanford 4,042 8,994NYP310%235%230%222% 3,065 6,764NYU221% 9,414 20,609UPMC219% 3,701 7,594Penn 2,238 4,452Emory 2,516 4,837*Duke*192% 6,587 12,478Northwell189% 2,775 4,845U Mich175% 1,381 2,388U Chicago173% 6,238 10,560Cleveland Clinic 9,292 13,708Mayo148% 9,507 13,951MGB (fka Partners)147% 1,181 1,719UVA 1,773 2,299Dartmouth205%199%169%146%130%SOURCES: Audited financial statements (AFS) or annual reports. * 1 billion was added to Duke to accommodate the practice plan.NOTES: End year is 2019 to avoid impacts of COVID-19 in 2020. All dollar values are shown in 2019 USD. Revenues for health systems fully integrated financially with their

Reproductions of this document may be made with written permission of Emory University's Woodruff Health Sciences Center by contacting Anita Bray, Emory School of Medicine, James B. Williams Medical Education Building, 100 Woodruff Circle, Suite A367, Atlanta, GA, 30322.