Transcription

ISSN 0974-7788Vol 1 Issue 1January-March 2010Publication ofDepartment of AYUSH,Govt. of IndiaInternational Journal ofInternational Journal of Ayurveda ResearchAyurveda Researchwww.ijaronline.com Volume 1 Issue 1 January - March 2010 IJARPages 1-62

EDUCATION FORUMGlobal challenges of graduate level Ayurvediceducation: A surveyKishor Patwardhan, Sangeeta Gehlot, Girish Singh1, H.C.S. Rathore2Department of Kriya Sharir, 1Department of Community Medicine, 2Faculty of Education, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, IndiaABSTRACTIn the present day scenario, Ayurveda is globally being perceived in several contradictory ways. Poor quality of Ayurvedagraduates produced as a result of poorly structured and poorly regulated education system is at least one of the importantfactors responsible for this scenario. The present study was carried out to evaluate the ‘Global challenges of graduatelevel Ayurvedic education’ and is based on the responses of Ayurvedic students and Ayurvedic teachers from variouseducational institutions of India to a methodically validated questionnaire. As the study indicates, the poor standard ofAyurvedic education in India is definitely a cause of concern. The curriculum of Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine andSurgery (BAMS) course of studies is required to be reviewed and restructured. The syllabi are required to be updatedwith certain relevant topics like laws governing the intellectual property rights, basic procedures of standardization ofmedicinal products, fundamental methods of evaluating the toxicity of the medicinal products, essentials of healthcaremanagement and the basics of cultivation and marketing of medicinal plants. Furthermore, the study suggests that theAyurvedic academicians are required to be trained in standard methods of research and documentation skills, and theeducational institutions are required to be encouraged to contribute their share in building up the evidence base forAyurveda in the form of quality education and research.Key words: Ayurveda education, global challenges, India, mailed surveyINTRODUCTIONPerceptions about Ayurveda in India and overseas haveundergone a phenomenal change during the last 20 to 25years. A large population from all over the world is attractedtowards this ancient system of healthcare because of theterms associated with it like ‘Holistic Medicine’, ‘Herbal’,‘Free from side effects’, ‘Mind, Body and Spiritual approach’etc. Centers offering ‘Panchakarma therapy’, ‘AyurvedicLifestyle Management’ and ‘Ayurvedic Massage’ are beingincreasingly established. The use of Ayurvedic medicineshas become accepted in other countries as well. For example,according to the 2007 National Health Interview Survey, morethan 200 000 US adults had used Ayurvedic medicine in 2006alone.[1] Marketing strategies of major pharmaceutical firmshave changed and ‘Ayurvedic wings’ of drug manufacturinghave begun. In 2007, there were more than 8400 licensedAyurvedic pharmacies in India and the approximate turnoverof this industry was Rs. 4000 crore, which accounted for nearlyAddress for correspondence:Dr. Kishor Patwardhan, Department of Kriya Sharir, Faculty ofAyurveda, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University,Varanasi, U.P. 221 005, India.E-mail: patwardhan.kishor@gmail.comDOI: 10.4103/0974-7788.59945a third of the total pharmaceutics business of the country.[2]Many medical schools and other institutes all over the worldhave started offering some degree or diploma in Ayurveda.Several publication houses of international repute have startedpublishing literature related to Ayurveda. Even the people withno formal Ayurvedic education have started showing interest inauthoring books and research papers on Ayurveda.[3] Ayurvedais being seen as a rich resource for new drug development bymodern day pharmacologists.[4]On the contrary, questions on safety and efficacy of Ayurvedicproducts are also being raised.[5,6] In 2004 December, Journal ofAmerican Medical Association (JAMA) published a researchpaper, which concluded that one of the five Ayurvedic HerbalMedicine Products (HMPs) produced in South Asia andavailable in Boston South Asian grocery stores containedpotentially harmful levels of lead, mercury and/or arsenic. Thepaper also suggested that the users of Ayurvedic medicine maybe at risk for heavy-metal toxicity, and testing of AyurvedicHMPs for toxic heavy metals should be made mandatory.[7] Thisconcern has led some countries like Canada to curb the importof Ayurvedic preparations from India. In 2005, the testing byCanadian Government revealed alarmingly high levels of heavymetals in the exported Ayurvedic medicinal preparations. Theanalysis highlighted the ‘higher than acceptable concentrations’of heavy metals such as lead, mercury and arsenic.[8] A similarInternational Journal of Ayurveda Research January-March 2010 Vol 1 Issue 149

Patwardhan, et al.: Global Challenges of Ayurveda Educationpaper appeared in JAMA in 2008 too, raising an alarm againstthe use of Ayurvedic products because of their possible heavymetal contamination.[9] National Policy on Indian Systems ofMedicine and Homeopathy , 2002 has also admitted that thesafety, efficacy, quality of drugs and their rational use havenot been assured in India. This document states that there isno assurance whatsoever that formularies and pharmacopeialstandards are being followed by the Indian Systems ofMedicine drug manufacturers.[10]Thus, Ayurveda is globally being perceived in severalcontradictory ways. Poor quality of Ayurveda graduatesproduced as a result of a poorly structured and poorly regulatededucation system is at least one of the important factorsresponsible for this scenario. The number of Ayurveda collegeshas increased phenomenally to 242, out of which, about 150colleges have been established after 1980. Though the CentralCouncil of Indian Medicine (CCIM) has implemented variouseducational regulations to ensure minimum standards ofeducation, there has been a mushroom growth of sub-standardcolleges causing erosion to the standards of education. Liberalpermission by the State Governments, loopholes in the existingActs and weakness in the implementation of standards ofeducation have been held responsible for this state of affairs.[11]Considering the above facts, the present study was plannedto evaluate the global challenges of graduate level Ayurvediceducation. The study is based on the perceptions of Ayurvedicstudents and Ayurvedic teachers from various educationalinstitutions spread all over India.STUDY DESIGNMethodMailed survey was the method that was used to carry out thepresent study.PopulationThe population for the present study was defined in terms of thestudents studying and teachers teaching in Ayurvedic collegesof India during the period of September 2005 to October 2008.Inclusion criteriaAll interns/house surgeons registered under Bachelor ofMedicine and Surgery (BAMS) course, who have successfullypassed their third professional BAMS examination in theAyurvedic colleges recognized by CCIM were included in thestudy. Students who have not yet passed their third professionalexaminations were excluded from the study to avoid possibleimmature and biased perceptions.All Post-graduate students registered for MD(Ay) or MS(Ay)courses in the Ayurvedic colleges recognized by CCIM were50also included in the study.All teachers working in Ayurvedic colleges / universitiesrecognized by CCIM, who possess at least a BAMS or anequivalent degree, were included in the study.SampleThe sample frame that became available constituted a list of242 Ayurvedic colleges spread all over India. As the studentsand teachers in these colleges formed the primary units ofsampling, it was essential to get a list of all these studentsand teachers for the purpose of randomization. But, as nosuch database is available in India, the list of 242 Ayurvediccolleges was accepted as the sample frame for this study. Withthe availability of the said sample frame, the Random ClusterSampling technique was considered to be the most appropriateone. Hence, it was decided to include at least 10% of the totalinstitutions present in a specific geographical zone of India(North, East, South and West). At the same time, an effortwas made to include as many states as possible. The collegesfrom each geographical zone were selected randomly andall the teachers and students from these colleges, as per theoperational definition stated earlier, were taken as the clustersto constitute the sample. Thus, a total of 32 colleges wereincluded in the study.Preparation of the QuestionnaireA preliminary list of items was prepared on the basis ofinteractions we had with the students and teachers of severaleducational institutions. Diverse sources of literature likereports of various committees, journals, news reports, nationalhealth policy documents and other articles were referredto for collecting the items. The questionnaire comprised ofthree sections dealing with three problem areas, viz., ‘JobOpportunities’, ‘Global challenges’ and ‘Entrepreneurshipopportunities’. The respondents were given the option ofrecording their responses in the form of ‘Strongly Agree’,‘Agree’, ‘Undecided’, ‘Disagree’ and ‘Strongly Disagree’ byrecording a check mark ( ) in the respective column providedfor the purpose. Apart from these statements, the respondentswere also asked to furnish some demographic details such astheir age, gender, institutional affiliation and the present status(student or teacher).Validation of the Questionnaire for its Reliability andConsistencyThe preliminary questionnaire was distributed to 150respondents who randomly fulfilled the inclusion criteria in asingle institution. The validation process of the questionnairewas carried out on the basis of the first 100 completedquestionnaires. The data entry was done using the software‘Statistical Package for Social Sciences’, Version 11.5 (SPSSInc. Chicago, IL, USA). Demographic data were fed inthe ‘String’ format and the responses to the questionnaireInternational Journal of Ayurveda Research January-March 2010 Vol 1 Issue 1

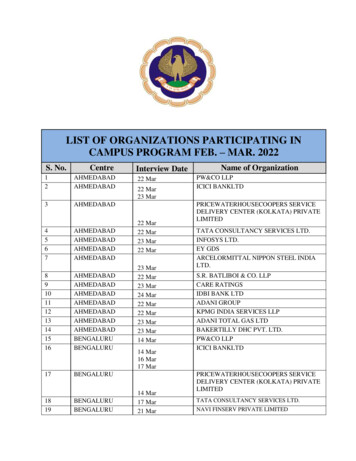

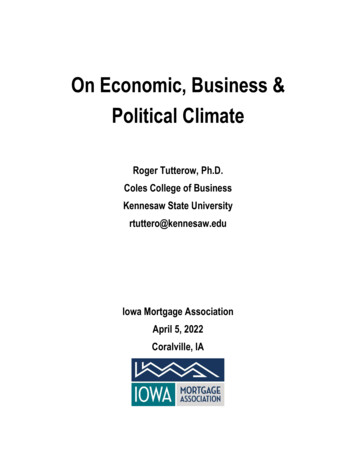

Patwardhan, et al.: Global Challenges of Ayurveda Educationwere entered in the ‘Numerical’ format. For the purposeof conversion of responses into the numerical format, thefollowing scoring system was used: Strongly Agree 5; Agree 4; Undecided 3; Disagree 2 and Strongly Disagree 1.For the purpose of validation, each section of the questionnairewas considered as an independent scale and these scaleswere tested for their reliability using ‘Cronbach’s CoefficientAlpha’.[12] While validating the scales, value of alpha greaterthan 0.7 and item-total correlation greater than 0.2 wereconsidered to be acceptable.[13] Wherever the value of ‘Alpha(when item deleted)’ was greater than Cronbach’s coefficientalpha, the corresponding item was deleted and the wholeprocess of validation was repeated and thereafter, the scaleswere finalized.The final questionnaire contained three sections (technically,three independent scales) comprising of a total of 24 items.Apart from these items, the questionnaire also contained acopy of confidentiality agreement stating the purpose of thestudy and assuring strict confidentiality of the respondents.Collection of DataAfter validation and testing the questionnaire for its reliability,the questionnaire was printed on the A4-sized paper andwas mailed to 32 Ayurvedic colleges. Varying numbers ofquestionnaires were mailed to different institutions consideringthe total admission capacity, the total number of teacherspresent, presence or absence of post-graduate courses etc. Theheads of the institutes were requested through a formal letterto distribute the questionnaire among interns, post-graduatestudents and teachers. A self-addressed stamped envelopewas also sent in order to facilitate the return of the completedquestionnaires. A period varying from 1 to 2 days was givento the respondents to return the completed questionnaires. Thecompleted questionnaires were then collected and the dataentry was carried out as explained earlier.Response RateThe response rate for the student group was 59.6% and for theteacher group it was 54%. A total of 1022 participants from 18states responded to the questionnaire. This number included644 students and 378 teachers.Tabulation and Statistical TestsThe participants were grouped under two categories: ‘Students’and ‘Teachers’. Tables of frequency and percentage wereframed on the basis of responses to individual items for eachgroup. Independent samples - t test was applied to comparethe mean scores of the two groups.RESULTSTables 1–3 summarize the results of the present study. Tablesshow the items covered in the final questionnaire along with themean scores for both the groups separately. Also, the results ofindependent samples - t test are shown in the form of t valuesand p values. As per the scoring pattern followed in the study,the mean scores greater than 3 indicate a tendency towardsagreement, whereas the mean scores lesser than 3 indicate atendency towards disagreement. Furthermore, the mean scoresgreater than 4 indicate a strong tendency towards agreement.As the tables show, mean scores for both the groups are greaterthan 3 for all the 24 items indicating a general tendency towardsagreement.DISCUSSIONJob opportunitiesThe observations related to this section [Table 1] of thequestionnaire indicate that there is a real problem related tothe job opportunities for BAMS graduates. Except for Q1.2and Q1.7, the tendency for agreement towards all the itemsis significantly stronger among students than the teachers asindicated by p values. This means that students perceive thisproblem to be a more serious one in comparison to teachers.This indicates that there is a considerable level of career-relatedanxiety among students. This anxiety is noticeably less amongteachers because they are already into a job.The Government is required to look into the matter relatedto the creation of job opportunities for BAMS graduates incertain departments like Railways and Defence. In teachinginstitutions too, some posts like tutors and medical officers maybe created for BAMS graduates. Ayurveda may be includedas an optional subject in the entrance examinations leadingto Indian Administrative Services (IAS) just like modernmedicine. If the quality of education is improved, some jobopportunities may open up in research institutes and in otherplaces in the healthcare industry as well.Global IssuesAs the Table 2 shows, both the students and the teachers showa strong tendency towards agreement that the issues related tosafety profile and standardization of Ayurvedic products areserious ones. A majority of students and teachers also tend toagree that in many countries, practicing Ayurveda is not legallyallowed and therefore, there are no opportunities for BAMSgraduates in such countries. Also, there is a general tendencytowards agreement that Ayurvedic academicians do not figureanywhere in authoring the scientific and evidence-based papersin reputed international journals and they do not voluntarilyparticipate in international platforms to present their researchdata. The study also suggests that Ayurvedic academicians donot follow international standards while planning the protocolsof research projects and while writing research reports.Ayurvedic scholars generally do not have knowledge regardingInternational Journal of Ayurveda Research January-March 2010 Vol 1 Issue 151

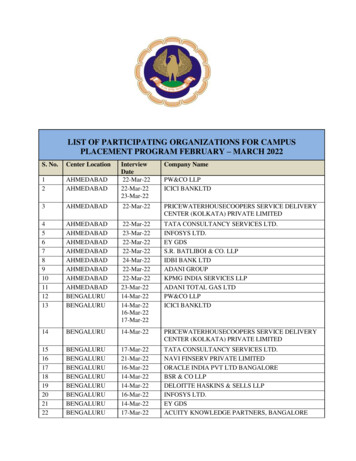

Patwardhan, et al.: Global Challenges of Ayurveda EducationTable 1: Responses of the participants to the items related to the ‘Job Opportunities after BAMScourse’. The mean scores for both the groups are given along with the results of Independentsamples-t test.GroupMean SDtpLegally, in most of the states, a BAMS degree holder cannot practiceAllopathy and therefore hospitals generally prefer MBBS graduates asmedical officers instead of BAMS graduates.Ayurvedic hospitals are less in number in comparison to Allopathicones and therefore job opportunities are limited.ItemsStudents4.39 0.9456.7320.000Teachers3.94 1.142StudentsTeachers4.41 0.8764.27 0.8812.4150.016Q1.3In Ayurvedic educational institutions, only Post-Graduate doctors areemployed and not BAMS degree holders.StudentsTeachers4.15 1.0643.81 1.1654.7170.000Q1.4Most of the research institutions prefer Post-Graduate doctors andtherefore, job opportunities in research institutions are limited.Students4.34 0.8302.8660.004TeachersStudentsTeachers4.19 0.8314.69 0.6104.53 0.7183.8080.000StudentsTeachers4.28 0.8034.09 0.8983.4760.001StudentsTeachers4.21 0.9554.14 1.0101.1400.255Q1.1Q1.2Q1.5Q1.6Q1.7Even in government sector, BAMS graduates are not treated at parwith MBBS graduates and therefore, job opportunities are limited incertain areas e.g. Railways.Ayurvedic pharmaceutical firms prefer Post-Graduate candidates toBAMS degree holders as experts.There is lot of competition for jobs among BAMS degree holders as aresult of mushrooming of Ayurvedic colleges.Table 2: Responses of the participants to the items related to the ‘Global Issues concerned toAyurveda’. The mean scores for both the groups are given along with the results of Independentsamples-t test.ItemQ2.1GroupMean us questions are being raised on the safety profile of Ayurvedicpreparations in some countries posing a threat to the Ayurvedicsystem of Medicine.Students4.27 0.867Teachers4.00 1.013Standardization of Ayurvedic preparations is still a problem thatneeds to be addressed.Students4.47 0.706Teachers4.31 0.738In many countries, legally, practicing Ayurveda is not allowed andtherefore, there are no opportunities for BAMS graduates in suchcountries.Students4.40 0.833Teachers4.27 0.792Possible entry of foreign universities in India may pose a threat to theexisting educational institutions.Students3.77 1.158Teachers3.51 1.202Ayurvedic academicians do not figure anywhere in authoring thescientific and evidence-based papers in reputed internationaljournals.Ayurvedic academicians do not voluntarily participate in Internationalplatforms to present their research data.Students3.95 1.081Teachers3.84 1.081Students3.79 1.131Teachers3.73 1.138Ayurvedic academicians do not follow international standardswhile planning the protocols of research projects and while writingresearch reports.Students3.86 1.045Teachers3.87 1.020Ayurvedic scholars generally do not have knowledge regarding‘Intellectual Property Rights’ and patenting procedures.Students3.97 0.943Teachers3.92 0.975Authentic websites providing up-to-date knowledge in Ayurveda arenot hosted by Ayurvedic institutions.Students4.20 0.918Teachers4.19 0.769Q2.10No standard international indexed and peer-reviewed journals arepublished by Ayurvedic institutions making it difficult for Ayurvedicresearches have global attention.StudentsTeachers4.19 0.8854.15 0.8530.6280.530Q2.11Pharmacodynamic/ pharmacokinetic properties / efficacy / safetyprofiles and chemical compositions of Ayurvedic formulations areyet to be established making it difficult for experts in conventionalmedicine to accept Ayurveda.Students4.25 0.8931.8960.058Teachers4.15 al Journal of Ayurveda Research January-March 2010 Vol 1 Issue 1

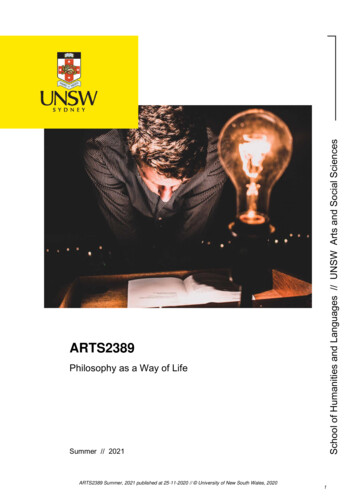

Patwardhan, et al.: Global Challenges of Ayurveda EducationTable 3: Responses of the participants to the items related to the ‘Entrepreneurship /Businessopportunities’ after the BAMS course. The mean scores for both the groups are given along with theresults of Independent samples-t test.ItemQ3.1Q3.2Q3.3Q3.4Q3.5Q3.6GroupMean SDtpStudents are not trained in management skills required to launch a newAyurvedic hospital / Panchakarma center / Ayurvedic Pharmacy duringBAMS course.Students4.18 1.0512.1700.030Teachers4.03 0.981Students are not exposed to the basics of economical aspects related tohealthcare sector during BAMS course.Students4.18 0.8902.0780.038Teachers4.06 0.856Most of the BAMS graduates prefer either studying PG course or theygo for private practice and therefore, inspiring examples of industriallysuccessful BAMS graduates are very few.Students4.38 0.7505.6930.000Teachers4.09 0.840Students are not introduced to the skills related to the management ofHealth tourism and emerging opportunities in this field during BAMScourse.Students are not exposed to the agricultural and marketing aspects ofmedicinal plants making it difficult to go for cultivation / marketing ofmedicinal plants.Students4.35 0.7822.4520.014Teachers4.23 0.776Students4.39 0.6903.4300.001Teachers4.22 0.800Students are not exposed to the manufacturing techniques related tocosmetic products and such other popular dosage forms during BAMScourse making them unfit for modern pharmaceutical industry.Students4.34 0.8673.1020.002Teachers4.16 0.864‘Intellectual Property Rights’ and patenting procedures, whichis another issue that this study is indicative of.The reasons for such perceptions need to be explored. Thecurrent curriculum of BAMS does not include the relevantand essential topics like laws governing the intellectualproperty rights, patenting procedures, basic methods ofstandardization of medicinal products, fundamental principlesof evaluating the toxicity of the medicinal products andbasics of pharmacovigilance. Experts in phytochemistry,pharmacognosy, pharmacology, biotechnology and otherrelevant fields may be appointed in teaching institutions asteachers to teach these topics. Basics of research methodologyare also not introduced in the present BAMS course of study.Some essential information related to these topics maybe introduced in the curriculum making BAMS graduatesconversant in these topics. Training programs and workshopsmay be required to be introduced for Ayurvedic academicians,where, training may be given in planning the researchprotocols, preparing the research projects and in other variousareas of research methodology.A very significant proportion of the students and the teachersin the present study tend to agree that authentic websitesproviding recent advances in Ayurveda are not hosted byAyurvedic institutions. In this regard, the education institutionsare required to be encouraged to host authentic websites givinginformation related to various aspects of Ayurveda. Classicaltextbooks of Ayurveda may also be made available online atthese websites along with the information related to recentadvances. The Government also may take initiative in thisregard and launch authentic websites.A significant number of participants in the study tend to agreethat no standard international indexed and peer-reviewedjournals are published by Ayurvedic institutions makingit difficult for Ayurvedic researches have global attention.However, recently, National Institute of Ayurveda (NIA),Jaipur and Institute of Post-Graduate Teaching and Researchin Ayurveda (IPGTandRA), Jamnagar have launched their ownpeer-reviewed journals, which is a positive sign. But their reachis limited by the fact that online versions of these journals arenot available. The department of AYUSH has recently takeninitiative in this regard by launching the International Journalof Ayurveda Research (IJAR), which is an online journal.A majority of students and teachers in the present study tendto agree that Pharmacodynamic / pharmacokinetic properties/ efficacy / safety profiles and chemical compositions ofAyurvedic formulations are yet to be established makingit difficult for experts in conventional medicine to acceptAyurveda. As a solution, the basic topics related to these issuesmay be incorporated into the curricula of BAMS and postgraduate courses of Ayurveda making the graduates and postgraduates of Ayurveda efficient in carrying out such studies.Entrepreneurship / Business OpportunitiesSo far, unlike conventional biomedicine or Allopathy,pharmaceutics has been a part of Ayurvedic educationin India in the form of ‘Rasashastra’. There is a need oftraining to be imparted in the basic knowledge related topharmaceutical industry during graduate level Ayurvediceducation. Furthermore, Ayurvedic pharmaceutics is based ona large number of medicinal plants and the basic knowledgerelated to the cultivation and marketing of these plants isInternational Journal of Ayurveda Research January-March 2010 Vol 1 Issue 153

Patwardhan, et al.: Global Challenges of Ayurveda Educationrequired to be passed on during Ayurvedic education. Thiswill make an Ayurvedic graduate have a lot of opportunitiesother than private practice. But, as the Table 3 suggests, suchentrepreneurship opportunities are scarce for BAMS graduatesbecause of poor training during their Ayurvedic education. Asa solution, some basic management skills that are essentiallyrequired to launch a new Ayurvedic hospital / Panchakarmacenter / Ayurvedic Pharmacy etc., may be included in thecurriculum. Also, basic cultivation and marketing aspects ofmedicinal plants are needed to be introduced at BAMS level.Some manufacturing techniques related to cosmetic productsand such other popular dosage forms may also be introduced.Introductory lessons in the management of health tourismmay also be incorporated during the graduate level Ayurvediceducation.1.2.3.4.5.6.7.8.CONCLUSIONAs the present study indicates, the poor standard of graduatelevel Ayurvedic education in India is definitely a cause ofconcern. The curriculum of BAMS course of studies isrequired to be reviewed and restructured. The syllabi arerequired to be updated with certain relevant topics like lawsgoverning the intellectual property rights, basic procedures ofstandardization of medicinal products, fundamental methodsof evaluating the toxicity of the medicinal products, essentialsof healthcare management and the basics of cultivation andmarketing of medicinal plants. Ayurvedic academicians arerequired to be trained in standard methods of research anddocumentation skills, and the educational institutions arerequired to be encouraged to contribute their share in buildingup the evidence base for Ayurveda in the form of qualityeducation and tm#ususe. [last accessed on 2009 Aug 14].Thatte U, Bhalerao S. Pharmacovigilance of ayurvedicmedicines in India. Indian J Pharmacol 2008;40:10-2.Wujastyk D, Smith FM, editors. Modern and Global Ayurveda,pluralism and paradigms. State University of New York Press(Publisher), ISBN: 9780791474891.Patwardhan B, Vaidya AD, Chorghade M. Ayurvedaand natural products drug discovery. Current Science2004;86:789-99.Thatte UM, Rege NN, Phatak S, Dahanukar SA. The flip sideof ayurveda? J Postgrad Med 1993;39:179-82.Gogtay NJ, Bhatt HA, Dalvi SS, Kshirsagar NA. The useand safety of non-allopathic Indian medicines. Drug Safety2002;25:1005–19.Saper RB, Kales SN, Paquin J, Burns MJ, Eisenberg DM,Davis RB, Phillips RS. Heavy metal content of ayurvedicherbal medicine products. JAMA 2004; 292:2868-73.News Report. Export of Ayurvedic medicines affecteddue to high heavy metal content. Available from: talContent-6365-1/. [last accessed on 2009 Aug 13].Saper RB, Phillips RS, Sehgal A, Khouri N, Davis RB, PaquinJ, et al. Lead, Mercury, and Arsenic in US- and IndianManufactured Ayurvedic Medicines Sold via the Internet.JAMA 2008;300:915-23.National Policy on ISMandH (2002). Government of India.Available from: andH-Homeopathy.pdf [last accessed on 2009Aug 10].Annual report on ISM & H 1999-2000. Department of IndianSystems of Medicine and Homeopathy, Government of India.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Cronbach's alpha.BMJ 1997; 314;572.Streiner D, Norman G. Health measurement scales: a practicalguide to their development and use. 2nd ed. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press; 1995.Source of Support: Nil, Conflict of Interest: None declaredInternational Journal of Ayurveda Research January-March 2010 Vol 1 Issue 1

All teachers working in Ayurvedic colleges / universities recognized by CCIM, who possess at least a BAMS or an equivalent degree, were included in the study. Sample The sample frame that became available constituted a list of 242 Ayurvedic colleges spread all over India. As the students and teachers in these colleges formed the primary units of