Transcription

The right to higher education:A social justice perspective

Published in 2022 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place deFontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and the UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in LatinAmerica and the Caribbean (IESALC). Edificio Asovincar, 1062-A. Av. Los Chorros con Calle Acueducto,Altos de Sebucán. Caracas, Venezuela. UNESCO 2022ISBN: 978-980-7175-67-8This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0IGO) license /). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access -use-ccbysa-en).The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not implythe expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of anycountry, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers orboundaries.The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarilythose of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization.Authors:Emma Sabzalieva, Daniela Gallegos, Clarisa Yerovi, Eglis Chacón,Takudzwa Mutize, Diana Morales, José Andrés CuadrosAcknowledgements:Rolla Moumné Beulque, Sharlene Bianchi, Allissa Kizer,Katherine Ann NguyenThis paper was supported in part through a grant from the OpenSociety Foundations.Copyeditor:Annette InsanallyGraphic design:Cesar VercherCover photo:iStockFor more information, please contact: info-IESALC@unesco.org 58 212 2861020www.iesalc.unesco.org

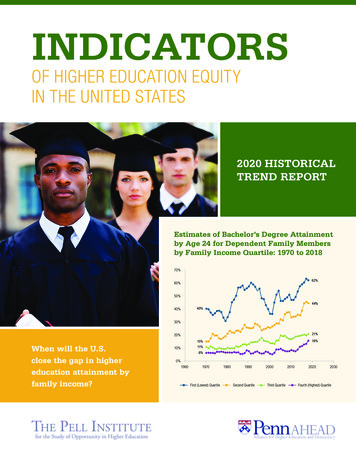

CONTENTSExecutive Summary. 51 Introduction. 6Objective and contents. 6The evolving right to education. 7The right to higher education as part of the right to education and lifelong learning. 7A social justice approach. 8The urgency of the right to higher education for a more socially just post-pandemic world. 92 A social justice perspective on the right to higher education. 10Features of a social justice lens on higher education. 10RTHE social justice framework . 103 Access to higher education. 16The narrowing education pipeline. 16Mass expansion of access to higher education. 17Impact of COVID-19 on access to higher education. 17Increasing access for equity deserving groups. 184 The need to rethink merit. 19Moving beyond ‘winners and losers’. 19Socio-economic factors. 20Quotas. 20Standardized testing. 21Use of contextual data. 21Higher education pathway programs. 225 Student success. 23Defining student success. 23Barriers to student success. 24Impact of COVID-19 on student retention. 25Academic and pastoral support. 25First-year students. 26Student engagement. 27Digital literacy. 27

6 Quality and relevance of provision. 28The importance of quality. 28Institutional differentiation. 28Specialized provision. 29Culturally appropriate provision. 29Online and distance teaching and learning. 30Open access to knowledge. 30Lifelong learning. 317 Institutional policies and administration. 32Leadership: Fostering a social justice mindset. 32Structural diversity. 32Administrative processes. 338 Higher education financing. 35Pressures on funding for higher education. 35Private higher education. 35The tuition fee debate. 36Living costs. 37Grants. 38Loans. 389 Human movement and international recognition of qualifications. 40Forcibly displaced people. 40Migration. 41International recognition of qualifications. 4210 Conclusion. 44Three areas for future consideration. 45References. 47The right to higher education: A social justice perspective4

ExecutiveSummaryThe right to education is a fundamental rightfor people and is integral to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Since the rightto education was first advanced at the international level in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the global landscape has changedimmensely. At the same time, higher educationhas progressed from being a pursuit for the elitein selected countries to being an integral partof the education continuum, accessed by atleast half of the population in many parts of theworld. Nevertheless, the right to higher education (RTHE) as part of the evolving landscape ofthe right to education has received less attentionthan education at other levels.education, and fair access to relevant and goodquality higher education. Once in higher education, the emphasis is on success, which, althoughan evidently subjective term, engages constructively with how to support students to fully participate, be well, and engage in good quality andrelevant higher education provision. Institutionalpolicies and administrative arrangements intersect in both processes of access and success, andit is there where the RTHE is engendered, in theperennial question of how to finance higher education, and how these processes translate acrossborders, considering human movement as a result of forced and voluntary migration, and theinternational recognition of qualifications.This conceptual paper advocates for the RTHEby developing a framework that takes a socialjustice perspective on this issue. Using a socialjustice lens, it highlights the unfair distributionof and lack of equitable access to higher education and the need for systems and institutionsof higher education to change to accommodatestudents’ diverse backgrounds and needs. TheRTHE social justice framework takes a systemicand structural approach to the issues facingstudents in higher education today. It embracesfour inter-related dimensions: the 5As framework, inclusive excellence, equity deservinggroups, and intersectionality. Under the socialjustice lens, each dimension attracts importantconsiderations relating to the RTHE.The conceptual paper identifies three areas ofgrowing concern – how to rethink ‘merit’, how tofund higher education, and how to assure students’ rights in a global context – and discussestheir implications for future considerations onthe RTHE. These are concerns because they haveno obvious solutions and because current globalcircumstances seem to be exacerbating them.Overall, this paper contributes to a better understanding of the RTHE as an integral componentof the evolving right to lifelong education, setting the context that will fuel continued researchand action so that the right to higher educationis truly a right enjoyed by all throughout life.The next step is to apply the social justice framework to the processes in higher education thatrelate to the RTHE. This starts even before astudent reaches higher education when theemphasis is on access: access to quality schooleducation that equips people well for higherThe right to higher education: A social justice perspectiveThis conceptual paper is linked to the RTHE project launched by UNESCO’s International Institutefor Higher Education in Latin America and theCaribbean (IESALC) in 2021 within the framework of UNESCO’s overall efforts to enhance theright to education at all levels.5

1 IntroductionSince the right to education was first advancedat the international level in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the global landscapehas changed immensely, with important consequences for education (UNESCO, 2000, 2022).Access to education has dramatically increased,rates of illiteracy have plummeted, and opportunities to embark on lifelong learning have greatly expanded as people are living longer and thenature of work is shifting. Education is no longeroffered only by states but by a range of providers including not-for-profit and commercialorganizations. Rapid technological change sincethe latter part of the twentieth century meansthat technology ‘has become an intrinsic part ofour day-to-day existence’ (UNESCO, 2022, p. 1),including in education.In this context of the evolving right to education,higher education has progressed from being apursuit for the elite in selected countries to beingan integral part of the education continuum, accessed by half or more of the population in manyparts of the world. The very existence of higher education, especially in countries that had previouslybeen subject to colonial domination, and its popularization, were factors not envisaged at the timethat the Universal Declaration came into effect(UNESCO, 2000). Furthermore, current political,social, and economic trends together with globalchallenges continue to question the concept ofhigher education – who it is for, how it should beoffered, and who takes responsibility for it.Objective and contentsTaking these considerations into account, theobjective of this conceptual paper is to advocate for the right to higher education (RTHE) aspart of the evolving right to education. To thisend, the RTHE is examined within a social justiceframework. This new approach to the issues facing students in higher education today is bothThe right to higher education: A social justice perspectivesystemic and structural. This conceptual paperforms part of a project dedicated to the RTHE,launched by UNESCO’s International Institute forHigher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (IESALC) in 2021, and is within the framework of UNESCO’s overall efforts to enhance theright to education at all levels.Section 2 of the conceptual paper identifies thelinks between higher education and social justice. It provides a four-dimensional frameworkfor examining the right to higher education(RTHE) using a social justice lens. The four dimensions – the 5 As framework, inclusive excellence, equity deserving groups, and intersectionality – focus on how systems and structures needto change so that students, who are at thecenter of higher education, have better opportunities to access higher education and betterchances of succeeding after they enroll.The framework developed in section 2 is thenapplied to those processes relating to higher education that are relevant when considering theRTHE. These commence even before a studentreaches higher education when the emphasisis on access: access to quality school educationthat equips people well for higher education,and then fair access to relevant and good quality higher education. These issues are taken upin section 3 on access to higher education andsection 4 on the need to rethink merit.Once in higher education, the next stage canbe called success, which, although an evidentlysubjective term, can be constructive in terms ofsupporting students to fully participate, be well,and engage in good quality and relevant highereducation provision. Section 5 of the conceptual paper addresses the issue of student successand section 6 examines the quality and relevance of the provision.There are three other issues which intersect withboth processes of access and success: the institu6

tional policies and administrative arrangementswhich engender the RTHE, addressed in section7; how to finance higher education, discussedin section 8; and how these processes translateacross borders, considering human movementresulting from forced and voluntary migration,and including the international recognition ofqualifications, which are examined in section 9.The final section of the paper compiles the keyfindings from the report and highlights threeareas for future consideration to develop theRTHE as an integral part of the evolving right toeducation.The evolving right to educationThe right to education is a fundamental rightof people and is integral to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948).UNESCO has been engaged in actions to broaden the right to education at all levels and considers education to be key to the full participationof all children and adults in the life of communities. For this reason, it is essential for educationto be freely accessible and guaranteed for all.The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), adopted in1966, emphasizes that ‘Higher education shallbe made equally accessible to all, on the basisof capacity, by every appropriate means, andin particular by the progressive introduction offree education’ (Article 13(2)(c)). The Conventionagainst Discrimination in Education (Convention against Discrimination in Education, 1960)establishes the obligation of the State to eliminate any form of discrimination in the field ofeducation and to promote equal opportunities(The Abidjan Principles’ Drafting Committee,2019; UNESCO, 2015, p. 7). Likewise, SDG 4 of theUN Sustainable Development Goals speaks toQuality Education and promotes lifelong learning which implies extending and recognizingthe right to higher education for all throughoutThe right to higher education: A social justice perspectivetheir lives. Indeed, access to higher education isa necessary condition to fulfil all SDGs (UNESCOIESALC, 2020b). The Abidjan Principles establishthat States must respect, protect, and fulfill theright to education of everyone, commit to providing public education, and to regulating theparticipation of the private sector in education(The Abidjan Principles’ Drafting Committee,2019). This clearly follows UNESCO’s ‘no one leftbehind’ policy (UNESCO, 2015, p. 7).The right to higher education as partof the right to education and lifelonglearningGlobal expansion and increased demand forhigher education has also been influenced bythe increased recognition of higher educationas a human right and the consequent advocacyof its importance (UNESCO IESALC, 2020). UNESCO’s commitment to the right to educationextends to all levels of education because theright to education is the right to lifelong learning. This is an agenda that has received renewedattention with the 2030 Agenda for SustainableDevelopment and as higher education institutions increasingly position themselves as spacesfor lifelong learning (Atchoarena, 2021).Nevertheless, the right to higher educationas part of this right has received less attentionin the past, despite higher education’s value atmultiple levels. For example, at an instrumentallevel, higher education enhances individual status through knowledge and diplomas, increasedpolitical awareness, the ability to function as aninformed or active citizen, the enjoyment of theexperience of studying at a higher level, and thevalue of interaction with other students and staffor making friends (McCowan, 2012). At an intrinsic level, higher education enables the acquisition of knowledge, supports deep enquiry, andcritical reflection (McCowan, 2012).7

Higher education is both a public good and acommon good. As a public good, higher education should be available to all and access to itshould not be impeded. This is reflected at thenational level within existing documents suchas legislation, national education plans andstrategies that emphasize quality assurance,non-discrimination, universal access, and inclusion as key components of the right to higher1education. As a common good, higher education ‘promotes the development of instrumentsof participatory democracy and places greateremphasis on networks of solidarity among citizens and groups to overcome the utilitarian andindividualistic approaches that the commercialization of higher education has brought in thelast decades’ (UNESCO IESALC, 2022d, para. 6).Every right in itself is unlimited and enduring innature, so the right to education should not haveany restriction or expiry time. For this reason,access to lifelong education must also always beguaranteed and, being a stage in the lifelong educational journey, higher education should alsobe considered a right that must be guaranteedto everyone. This is why UNESCO considers that‘raising awareness on the right to higher education as a social justice imperative is not onlytimely, but also crucial in respect of the princi2ples and obligations that relate to this level.’A social justice approachSocial justice is a broad spectrum, coveringmany major social issues such as wealth, land,property, the environment, race and gender. Thepursuit of social justice can be seen as the searchfor a fair (not necessarily equal) distribution ofwhat is beneficial and valued in a society. Suchbenefits are not only in the form of materialadvantages but include non-material targetsas well, for example, access to possibilities forextending ‘people’s democratic ability to shapetheir lives’ through real choices (Gindin, 2002, p.1). Thus, social justice has associations with notions of human and socio-economic rights, socialinclusion, equity and access to resources and capabilities for human wellbeing (Singh, 2011).Social justice work addresses inequality andoppression in all its nuances, including but notlimited to racism and xenophobia, classism andeconomic discrimination, sexism and misogyny,homophobia, religious and political persecution,the abuse of civil liberties, and ableism (Rankinet al., 2010; Gordon et al., 2018). When thesefactors determine what kind of an educationan individual can receive, that is an example ofsocial injustice. Social justice in education refersto a commitment to challenging social, cultural,and economic inequalities imposed on individuals arising from any differential distribution ofpower, resources, and privileges (Mills School ofEducation, 2019). At the compulsory levels – thatis, primary and secondary education – the socialjustice lens is more visible as education at these3levels is a right and its non-fulfillment has to dodirectly with socio-economic barriers that do notdepend on choice.By examining the current higher educationlandscape using a social justice lens, its unfairdistribution and inequitable access based ongeographic and socioeconomic backgroundscome to the fore. A social justice perspectiveexamines the very structure of higher educationitself and what the systems and institutions ofhigher education need to change to accommo-1 Examples are lodged in the UNESCO Right to Education Observatory at tabase anddiscussed in the UNESCO policy paper, The Right to Higher Education: Unpacking the International Normative Framework in Light of CurrentTrends and Challenges.2 er-education/3 According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 26: ‘higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis ofmerit’The right to higher education: A social justice perspective8

date students’ diverse backgrounds and needs.This fundamentally changes the focus from previously dominant approaches that have tendedto assume that individual students need to be‘fixed’ to fit in with the dominant (typically Eurocentric) conception of higher education.The urgency of the right to highereducation for a more socially just postpandemic worldThe evolving COVID-19 pandemic has disruptedhigher education in myriad ways and in particular, it has laid bare longstanding issues of socialjustice and exposed a digital divide (Sabzalievaet al., 2021). Although every group and sectorhas felt the effects, these impacts have variedwidely and had the greatest impact on minoritized communities (Hottenstein et al., 2021). Theintersection of the pandemic and equity challenges have seriously impacted students andinstitutions (Kelly, 2021).Some institutions are declaring fiscal crisis andinitiating funding reforms to close financialgaps in an effort to survive, further exacerbatingpressures on families and young people who areseeking post-secondary educational achievement as their road to success. These additionalchallenges have put first-generation students,immigrants and other vulnerable populations atrisk of unequal educational opportunities andprofessional development (Taner, 2021). In thiscontext, it is particularly relevant to defend theright to higher education so that economic responses to the crisis are not implemented at theexpense of students’ wellbeing.hel, 2020), which poses significant barriers tothe exercise of the right to higher education as itimpacts learning and the successful completionof studies. With a changing landscape, the sectornow faces a critical need for transformation thatought to promote social justice principles by encompassing inclusivity, equitability, accessibility,and connectivity (Fraser-Moleketi, 2021).On the other hand, the pandemic has shownthat higher education is key to developing solutions and helping society to envision a fairerworld. In particular, higher education has hada key role in knowledge production, and it hasactively engaged in institutional responsibilityto advance social justice for learners and theircommunities (Bergan et al., 2021). From creatingawareness about rising inequalities, to direct engagement with communities, public and privatestakeholders, the importance of higher education has become even more evident during thepandemic. Despite the barriers higher educationhas faced, especially regarding teaching andlearning, global examples of resilience, resistance, and innovation show how the RTHE is animperative to support the work and advocacy fora just society in the years to come.In addition, the move to deliver higher education purely online has been seen as

launched by UNESCO's International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Carib-bean (IESALC) in 2021, and is within the frame-work of UNESCO's overall efforts to enhance the right to education at all levels. Section 2 of the conceptual paper identifies the links between higher education and social jus-tice.